The Bank Tax Shuffle: House weakens HB 510, adds exemptions

June 12, 2012

The Bank Tax Shuffle: House weakens HB 510, adds exemptions

June 12, 2012

Press releaseDownload executive summaryDownload full reportThe proposed Financial Institutions Tax would provide millions in tax cuts to mortgage lenders, securities brokers, payday lenders, finance companies, and other so-called “dealers in intangibles.” It also would create a new way for insurance-company affiliates to cut taxes between now and 2014 by restructuring operations, and add other new exemptions.

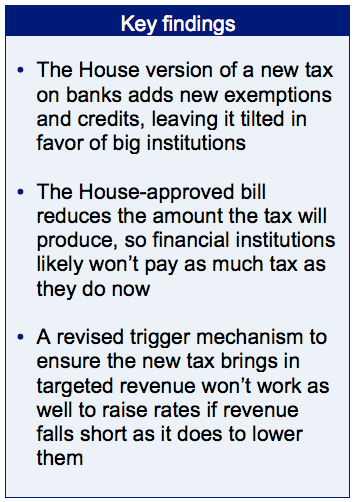

A new tax on Ohio’s banks, a chief aim of which originally was to cut loopholes in the old taxes, would add new exemptions, credits and exclusions in its latest version. One result: Mortgage lenders, securities brokers, payday lenders, finance companies, and other so-called “dealers in intangibles” would get a huge tax cut. According to the Ohio Department of Taxation (ODT), such dealers that are not affiliated with other financial institutions would see their overall taxes fall from $20 million a year to no more than $4 million.[1] Another portion of the bill provides an open invitation to insurance-company affiliates to avoid additional taxes between now and 2014 by taking advantage of an exemption from the Commercial Activity Tax.

These are just some of the ways that the House of Representatives weakened the tax proposal, House Bill 510, before passing it in May. It is now under consideration in the Senate. Besides reducing the revenue the tax will generate, a host of new provisions would chip away at the base of the new tax and continue to leave big banks with a large share of the proposed rate cuts.

Financial Institutions Tax

The Kasich administration first proposed the new tax as a part of its Mid-Biennium Review. The Financial Institutions Tax (FIT) would replace the corporate franchise tax and the tax on dealers in intangibles, respectively, on what was said to be a revenue-neutral basis.[2] Tax Commissioner Joseph W. Testa outlined in legislative testimony how companies currently are able to legally avoid Ohio’s existing taxes for financial institutions because of the way they are set up.[3] By forcing financial institutions to report all of their equity capital on a consolidated basis and eliminating a big exemption, the new tax would cover a far larger base than the existing corporate franchise tax and undercut such tax avoidance.[4] Unfortunately, and contradictory as it might seem, the original proposal as well as the House-approved version would funnel what should be added revenue for the state right back to the banks.[5] The General Assembly should stick with the original attempt by the Kasich administration to cut loopholes – but without cutting rates on big banks, in particular.

It is difficult to parse all the details of the proposal to determine how much financial institutions will pay under the new tax regime compared to what they do now. However, it appears likely that they will pay less. “The bill as it stands now represents a careful compromise that has traded some expectation of future FIT revenue for greater taxpayer certainty and a lower risk of tax increases for current Ohio taxpayers,” concluded Commissioner Testa in his letter to the senate president.[6] He noted that the annual revenue target had been adjusted downward from $225 million to $200 million “to reduce the number of taxpayers who might face tax increases due to the proposal, and to minimize any increases that might occur.” In its fiscal note on the House-approved bill, the Legislative Service Commission said, “Overall, the bill may decrease GRF revenue by an uncertain amount, though the revenue loss may be up to $30 million per year, when compared to the introduced version of the bill.”[7]

Rep. Ron Amstutz, lead sponsor of the bill, responded to reports that it would lead to a $25 million to $30 million tax break to banks and other financial institutions in a June 1 memo to members of the General Assembly.[8] In it, he argues that the original proposal would have resulted in “a major tax increase for non-bank financing entities,” so the House Ways & Means Committee placed them under the Commercial Activity Tax instead of the new FIT. However, this amounts to special treatment for certain entities, all involved in financial businesses, that should be taxed equally on those financial businesses. It’s certainly possible that some captive finance companies of manufacturers and retailers that currently pay the CAT, for instance, might pay more if they instead had to pay the new Financial Institutions Tax.[9] However, the overall effect of the House change is a tax cut – and the point of a tax reform is to simplify and make the playing field level for taxpayers that are similarly situated.

It’s especially inappropriate to tax dealers in intangibles under these two different taxes, the FIT or the CAT, depending on whether they are affiliated with a financial institution or not. The Commercial Activity Tax was never meant to cover financial institutions. As the tax commissioner told Niehaus in his recent letter, the CAT exempts most interest income, which accounts for much of the revenue these entities generate.[10] Taxing similar businesses differently, as the House changes do, is the exact wrong way to set up a new tax.

The new rate structure calls for three brackets, compared to two in the original bill: Those institutions with equity capital below $200 million will pay a rate of 8 mills, or 0.8 percent; capital between $200 million and $1.3 billion will be taxed at 4 mills, or 0.4 percent; and capital over $1.3 billion will see a lower rate still, 2.5 mills or 0.25 percent.[11] The vast bulk of Ohio’s banks and savings and loans will fall into the first group, which means that they will still receive a rate cut from the current 13 mills. The taxation department estimates that a dozen financial groups[12] will fall into the middle group, while 9 or 10 will be large enough to benefit from the 0.25 percent rate. It has not provided data on how many institutions or groups will fall into the 0.8 percent bracket, but it’s a much larger number. In Tax Year 2010, a total of 381 banks and other financial institutions reported tax liability under the corporate franchise tax, and though that number may well decline under the FIT, it will still be in the hundreds.

A regressive tax

The FIT is a regressive tax – the larger an institution is, the less it pays as a share of its capital. Overall, the proposal to cut rates was based on a Kasich administration objective to make the new tax revenue-neutral. In a May 21 letter to Senate President Thomas E. Niehaus, Tax Commissioner Testa noted that the change to consolidated reporting called for in the bill by itself would mean, according to ODT simulations, “that larger institutions have a greater increase in their tax base.”[13] Hence, to offset this, the proposal called for a lower rate for big banks.[14] But it is these same institutions – the largest ones – that have engaged in the tax avoidance the bill was designed to prevent. Instead of requiring them to pay what they should have all along, the bill gives them a break, because otherwise their taxes would go up disproportionately. At the very least, the bill should set the rates so that the tax brings in what is being collected now plus taxes that are now being avoided.

Moreover, state taxes on financial institutions have not kept up with industry growth since the mid-1990s.[15] Overall, the taxes that the FIT would replace are considerably lower in inflation-adjusted terms than they were in 1998. This suggests that the original $225 million annual revenue target was set too low, not too high.

The House-approved version of the bill chips away at the tax base with a slew of changes. Among other things, it:

- Exempts those dealers in intangibles that are not affiliated with a financial institution from the FIT and instead would have them pay the Commercial Activity Tax. Estimated cost: $16 million to $20 million a year. That benefit will probably go to a majority of the 256 dealers that filed returns for Tax Year 2011.[16]

- Allows the research and development tax credit to be applied against the tax. Cost: No dollar estimate, but assumed to be less than $1 million. It also allows other tax credits to be applied against the new FIT, the cost of which the taxation department has not yet estimated.

- Prohibits assessing affiliates of an insurance company for unpaid CAT before 2014, provided one of the company’s affiliates paid the franchise tax. Incredibly, this provision would encourage new tax avoidance, since it would allow companies to take additional steps such as restructuring their businesses to avoid more tax until 2014. The administration is still hoping to limit that by setting a date earlier than January 2014. Estimated one-time cost: $15 million to $20 million.

- Excludes certain "diversified savings and loan holding companies" and "grandfathered unitary savings and loan holding companies." Instead, they will pay the CAT. ODT told Niehaus it was unable to estimate the impact of these exclusions.[17]

It’s difficult to know who will really benefit from some of these changes. As one knowledgeable authority on Ohio state taxation put it, “If you’re not an officer or an employee of those companies or their representatives, you really don’t know all the impacts.” However, there’s little question that the positive aspect of the original proposal – to bring financial institutions under a single tax and eliminate a costly exemption, thus reducing the opportunities for tax avoidance – has been undercut.

An unbalanced trigger

The bill includes a trigger mechanism to ensure that revenue comes in close to the $200 million annual target. However, in the House version, this trigger is stronger in correcting greater-than-expected performance than it is if the tax brings in less than expected. And since the various exemptions and credits have been added, the need is for a stronger upward trigger. The House did add a second trigger covering a later time period, but it still leaves open the possibility that the new tax will not bring in even the lower $200 million in annual target revenue.

Under the new trigger mechanism, if the tax produces less than the target amount, the rate will be adjusted for 2015 not to produce the full $200 million, but 10 percent less than that, or $180 million. This contrasts with a full downward adjustment, to the $200 million target, if revenues come in stronger than anticipated.

The House added a second trigger, based on tax year 2016. If no rate adjustment is made for the first trigger period, the revenue target for this period would be $212 million; if it is adjusted downward in the first period, the new revenue target for 2016 would be $190.8 million. Revenue would have to drop below $171.7 million for an upward adjustment to be made after this second target period. While there was no second trigger in the original bill, this amount is considerably less the original target. And the various other changes in the bill adding new exemptions and credits add to the likelihood that the tax will underperform.

One other change that the House made to the trigger mechanism is revealing for what it shows about changes it made in the legislation. If rates are increased under the trigger in the House version, only the largest taxpayers will be affected, instead of all taxpayers, as originally proposed. The upward rate adjustment will apply only to the 0.25 percent rate, affecting the very few taxpayers with more than $1.3 billion in Ohio equity capital. Testa explained: “The House made this change in recognition of the fact that that the changes that were being made to potentially reduce the tax base, in order to minimize the number of taxpayers who might see a tax increase under the reform proposal, were mostly being made for larger taxpayers and so the risk of upward rate adjustment would also be placed on the largest taxpayers.”[18]

Conclusion and recommendations

The House bill, in short, is tilted to help big financial institutions. This is a dubious policy objective. Big banks aren’t better banks, as their role in the recent financial crisis made clear. The recent settlement of five big banks with state attorneys general over robo-signing of mortgage documents and other questionable practices further attests to this.[19] In a recent column in The Wall Street Journal entitled, “Big Banks Are Not the Future,” economist Henry Kaufman argued that shareholders should insist that financial conglomerates divest some of their activities, become more focused and “reduce their operations to manageable proportions.”[20] So why would the state of Ohio adopt a new financial institutions tax favoring big institutions?

According to the taxation department, banks are avoiding tens of millions of dollars a year in taxes through the legal use of today’s tax code. The loopholes should be closed, but the proceeds should not be redistributed to the banks. The big banks, in particular, should pay more than they do now, reflecting the end of loopholes they previously enjoyed. The new tax should not create new means of tax avoidance and the trigger should be strengthened so it corrects as much on the down side as it does on the up side. The FIT should increase revenue, to provide aid to fight the foreclosure crisis and to restore public services that have been undercut in the current state budget.[21]

[1] Joseph W. Testa, Tax Commissioner, letter to Ohio Senate President Thomas E. Niehaus, May 21, 2012. The exact beneficiaries of this are not publicly known. Among the 20 largest taxpayers in Tax Year 2010 accounting for more than three-quarters of liability for dealers in intangibles, the bulk of the liability was from companies that do mortgage lending and from securities broker-dealers (email from taxation department to the author, June 1, 2012. These companies also provide other services). However, it’s not clear if the dealers unaffiliated with a financial institution would break down along the same lines.

[2]The tax on dealers in intangibles, a holdover from when Ohio had a wealth tax, covers companies that lend money, buy or sell stocks and bonds, and others that are not banks, financial institutions or insurance companies.

[3] Joseph W. Testa, Testimony on Tax Provisions of House Bill 487, House Ways & Means Committee, March 21, 2012

[4] Altogether, the department estimates, the tax base will nearly triple under its new definition, so that were the existing 13-mill rate retained, it would generate tax liability of $523 million before credits compared to $181 million in Tax Year 2011. Ibid., p. 4

[5] For a more detailed report on the original FIT proposal, see an earlier Policy Matters Ohio report, Bank tax cuts loopholes, reduces rates: Proposal also provides unneeded help to big banks, April 12, 2012, at http://bit.ly/MDjEvI.

[6] Testa, op. cit., p. 6. Testa noted in his letter that the revenue outcomes are based on estimates and subject to uncertainty.

[7] The LSC note also said: “Though no FY 2014 official revenue forecasts have been published, it is probable the FIT may generate GRF revenues lower in magnitude than receipts from the CFT and the DIT. It is also possible, however, that the FIT may yield revenue higher than the CFT in FY 2014, based on reported tax liabilities in most recent years.” Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Jean J. Botomogno, Fiscal Note & Local Impact Statement, Sub. H.B. 510 of the 129th General Assembly, May 16, 2012, p. 4, available at http://bit.ly/KnqUH8. Both Testa’s letter and the LSC conclusion were reported in The Columbus Dispatch. See Jim Siegel, “Revised Bill Could Cut Banks’ Taxes,” May 22, 2012.

[8] State Rep. Ron Amstutz, Financial Institutions Tax Bill – H.B. 510, to members of the 129th General Assembly, June 1, 2012.

[9] Amstutz noted in his memorandum that the House changed how we would tax “entities like credit arms of auto manufacturers and retailers, or entities that provide internal financing across sister businesses that are commonly owned. Whether this was the best landing place for how to tax these organizations is a legitimate issue for legislators to examine with all involved. But it is not a question of whether this change would reduce taxes to any banks or savings and loans.” That’s true, but it does represent a tax cut for financial institutions.

[10] Testa letter, p. 4

[11] Originally, the bill called for one bracket for institutions with equity capital up to $500 million, which would be taxed at an 8-mill rate, and a second bracket for equity capital over $500 million, to be taxed at the 2.5 mill rate. Amstutz noted in his memo to legislators that the House-approved bill also lowered the revenue target by $5 million because it created the new, middle bracket for medium-sized banks and savings and loans. They were going to experience substantial tax increases under the two-bracket FIT as originally proposed, he said. Amstutz also claimed that the revenue target was inflated. However, the taxation department’s estimates merely added up all of the tax liability that financial institutions have been seeing, and came up with a tax structure that would produce a similar amount of revenue. Perhaps it’s reasonable to set up the tax so it falls less on medium-sized banks, but there is no reason for an overall tax cut.

[12] In simulating the new FIT, the taxation department looked at groups of financial companies that would pay the new tax together. This could involve entities that today are not combined for tax reporting purposes.

[13] Testa letter, op. cit., p. 3. The letter also noted that the choice of an 8-mill rate was in part based “on the desire not to impose a higher tax on dealers who would move from paying the dealers tax to paying the FIT as part of a consolidated FI group.” This is tail-of-the-dog reasoning: Because 250 financial companies have benefited for years from a special tax, all of the banking industry now should follow along after this outmoded tax? Better instead that the dealers pay what the banks have all along. That’s what a bipartisan committee recommended in 2003. See Report of the Committee to Study State and Local Taxes, March 1, 2003, p. 98, available at http://bit.ly/Mqberw and also Zach Schiller, Limiting Loopholes: A Dozen Tax Breaks Ohio Can Do Without, Policy Matters Ohio, September 2008, p. 5, available at http://www.policymattersohio.org/limiting-loopholes-a-dozen-tax-breaks-ohio-can-do-without.

[14] If the existing 13-mill rate were retained and the base broadened as the bill proposes, the taxation department estimates that the nine or 10 financial groups with more than $1.2 billion equity capital would pay $150 million in tax on that share of their equity (Email from Ohio Department of Taxation in response to a Policy Matters Ohio inquiry, May 18, 2012). That amounts to five times the amount that bracket will capture under the bill now.

[15] See Zach Schiller, Bank tax cuts loopholes, reduces rates, Policy Matters Ohio, April 2012, p.5, available at http://www.policymattersohio.org/bank-tax-april2012

[16] Ibid, and email from ODT, May 18, 2012.

[17] Testa letter op. cit.

[18] Testa letter, op. cit., p. 6

[19] Schwartz, Nelson D. and Shaila Dewan, “States Negotiate $26 Billion Agreement for Homeowners,” The New York Times, Feb. 8, 2012

[20] Kaufman, Henry, “Big Banks Are Not the Future,” The Wall Street Journal, June 6, 2012, p. A15

[21] See Zach Schiller, Bank tax cuts loopholes, reduces rates, Policy Matters Ohio, April 2012, p. 9, available at http://www.policymattersohio.org/bank-tax-april2012

Tags

2012Tax ExpendituresTax PolicyZach SchillerPhoto Gallery

1 of 22