Medicaid provider tax fix must not hurt counties, transit agencies

July 12, 2016

Medicaid provider tax fix must not hurt counties, transit agencies

July 12, 2016

Contact: Wendy Patton, 614.221.4505

By Wendy Patton

Executive summary

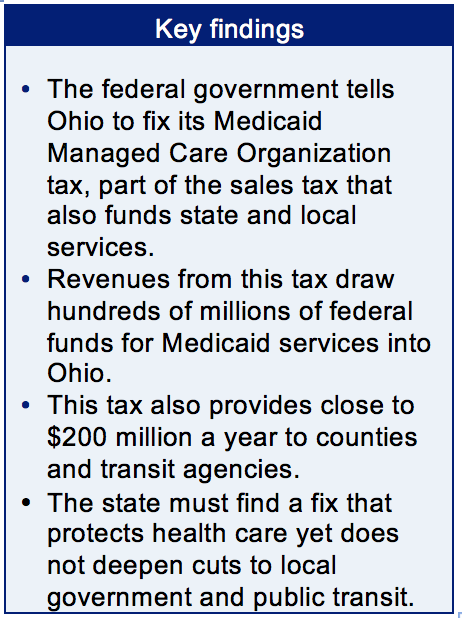

Unless Ohio changes a tax that helps people without insurance get health care, hundreds of thousands could have trouble getting medical services. In making changes required by the federal government, it is crucial to make sure local governments and transit agencies – which also benefit from this revenue – do not lose much-needed financial support.

Unless Ohio changes a tax that helps people without insurance get health care, hundreds of thousands could have trouble getting medical services. In making changes required by the federal government, it is crucial to make sure local governments and transit agencies – which also benefit from this revenue – do not lose much-needed financial support.

Medicaid managed care companies in Ohio pay sales tax on the health services they provide. The tax that they pay is calculated into the Medicaid payments they receive for delivering those services. The tax is referred to as an MCO (managed care organization) tax. Collections of this type, in Ohio and nationally, are used to draw down hundreds of millions of dollars in federal matching funds for Medicaid services.

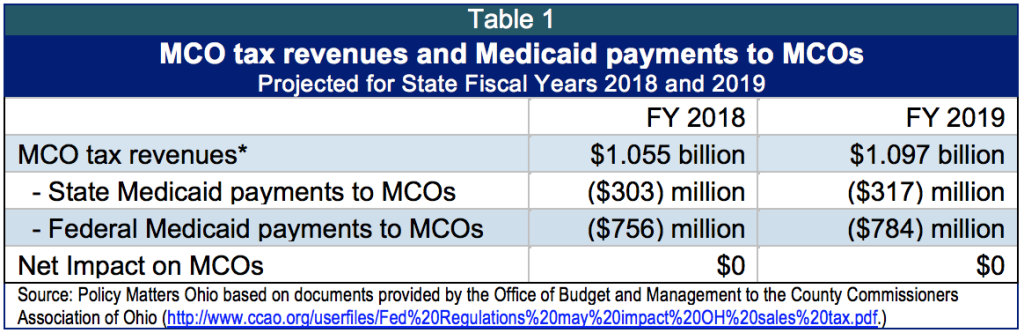

A July 2014 letter from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services warned all state Medicaid directors that taxing a subset of providers (like Medicaid managed care organizations) within a broad tax, like the sales tax, might no longer conform to federal rules. Several states with taxes like Ohio’s, including Michigan, California and Pennsylvania, have changed or are changing their MCO taxes. Ohio will as well.In state fiscal year 2018, tax collections from the Medicaid MCO tax will be just over a billion dollars. The state uses $303 million to draw down $756 million in federal matching funds. The remaining $558 million in MCO tax collections go in the state’s general revenue fund (GRF). The net impact of the tax on the MCOs is negligible because the tax payment is calculated into the MCO “capitation” rate, their payment for Medicaid services.

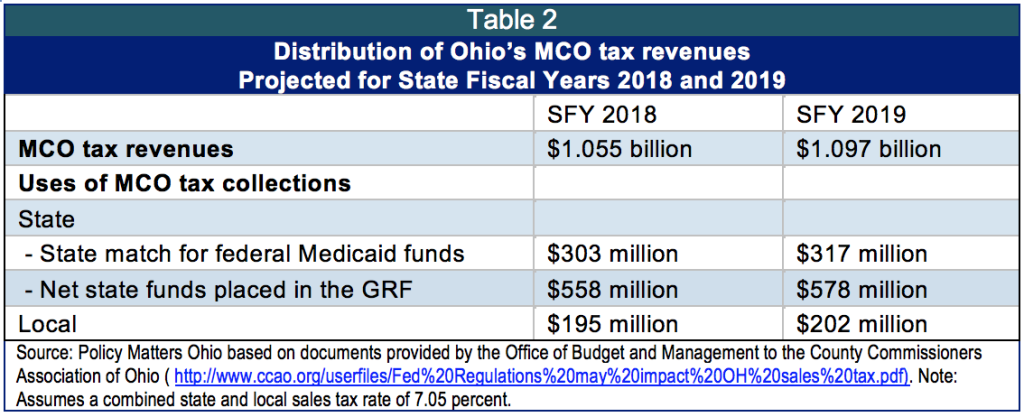

Local governments – counties and transit authorities – will collect an estimated $195 million dollars in fiscal year 2018 from this component of the sales tax base.

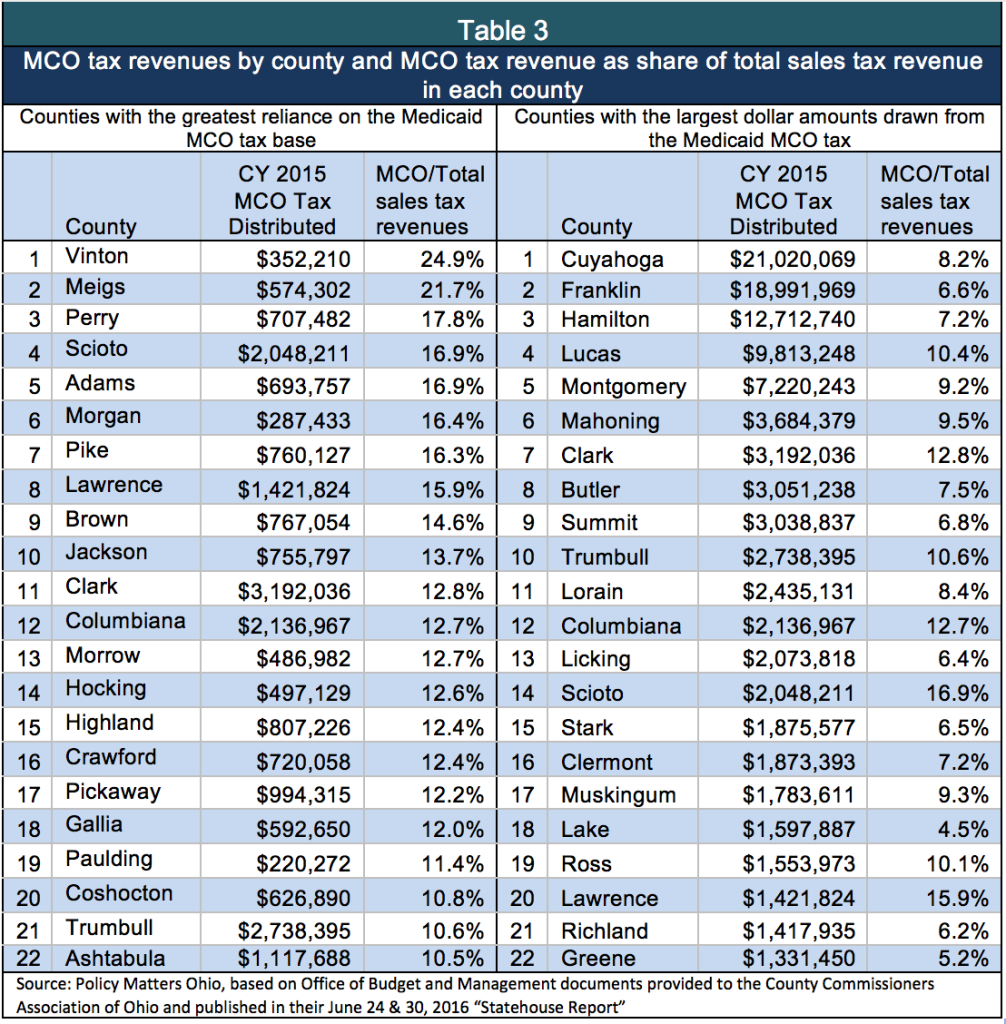

In Ohio, counties and transit authorities are authorized to levy a local sales tax on the state tax base. (commonly referred to as a “piggyback tax”). Such local taxes ranging from a half percent to 2¼ cents. Counties in Ohio’s Appalachian region, some of the poorest places in the state, are the most reliant on the Medicaid MCO sales tax collections because many residents are enrolled in Medicaid. The largest impact in terms of dollars, however, is on urban and suburban counties.

MCO tax collections are magnified by their role in financing public transit. Hundreds of thousands depend on public transit to get to work and the grocery store. Public transit has been badly cut by state government in the past two decades. If the MCO tax was removed from the sales tax base, transit agencies could lose more than $30 million a year.

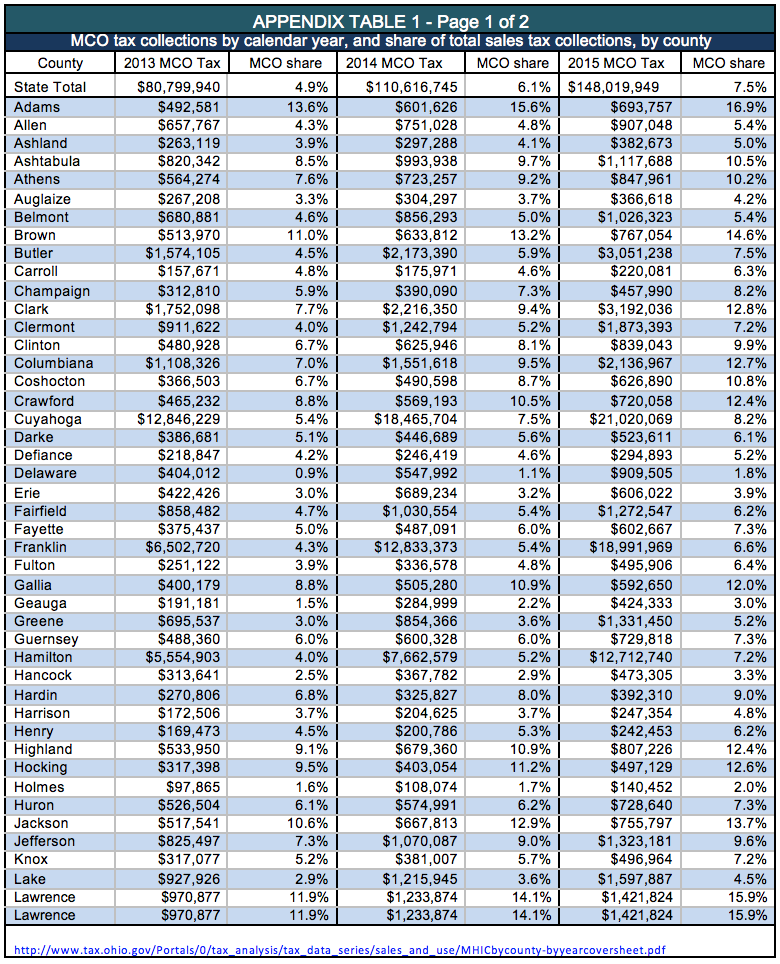

Statewide, the share of the MCO revenue in the local sales tax base increased from $81 million in 2013, about 5 percent of the local sales tax base that year, to $148 million in 2015, about 7.5 percent. In dollar terms, this represents growth of almost 83 percent. Growth remains robust: The MCO tax is forecast to bring $195 million to these local governments in 2018 and $202 million in 2019.

The problem Ohio and other states must fix in their MCO tax structure has nothing to do with the Affordable Care Act or the extension of Medicaid to low-income adults without custody of children; it has to do with federal rules that have changed over time. Other states have aligned their MCO taxes with federal requirements, ensuring solid, adequate finances for health services. Ohio can do the same. What is different about Ohio, and critical to any solution here, is that local governments depend on a local sales tax to fund services. Safety, fire, emergency services, road maintenance, snow plowing and all the civic services that underpin our daily lives must be protected.

This is not all that state government should do for Ohio localities. The budget for 2018-19 should restore levies that fund seniors’ and children’s services which have been hollowed out by loss of tax reimbursements; restore revenue sharing with cities, villages, townships, counties and special districts that have lost, on average, 50 percent of state local government funds; and restore the estate tax, which was an important source of funding for capital equipment for Ohio’s communities, on the heirs of Ohio’s wealthiest estates – those over a million dollars. These should remain a priority. This history of damage to local finances, however, highlights why it is essential that the solution crafted for Ohio’s MCO tax does not further harm Ohio’s communities and local public services.

Local governments have already been cut too deeply in Ohio. Ohio’s counties provide many important services in which state funding plays too small of a role. Ohio ranks 50th among states in support of children’s services, leaving poor counties struggling to protect their most vulnerable. The state budget supports adult protective services at a level far below needs at a time when the population is aging and more elders than ever need protection from abuse. Since 2010, the state has cut almost a billion dollars a year in resources of local governments through cuts in revenue sharing and changes in tax policy.

Any “fix” to the MCO tax that exposes local public services to further loss is not a comprehensive solution. It is the responsibility of state government to fix the MCO tax problem in ways that bring state health care taxes into conformance with federal standards, without hurting Ohioans who depend on local services. The lesson from other states is that this can be done.

Introduction

Unless Ohio changes a tax that helps people without insurance get health care, hundreds of thousands could have trouble getting medical services. In making changes required by the federal government, it is crucial to make sure local governments and transit agencies – which also benefit from this revenue – do not lose much-needed financial support.The federal government has warned Ohio to change an element in the base of the sales tax that supports Medicaid services. The connection to local governments is that they “piggyback” on the sales tax. If the sales tax is changed in certain ways, those local entities would lose revenue on top of five years of declining state support that has already brought serious reductions in services people rely on.

Medicaid managed care companies in Ohio pay sales tax on the health care services they provide, and the tax that they pay is calculated in to the Medicaid “capitation” rates, or the payments they receive for delivering those services.[1] The tax is referred to as an MCO (managed care organization) tax. Collections from this type of tax, in Ohio and nationally, are used to draw down hundreds of millions of dollars in federal matching funds for Medicaid services. In Ohio, the state collects more than $850 million from this tax and draws in hundreds of millions of federal taxes. In addition, counties and transit agencies that charge local sales taxes get about $200 million a year from this tax.

Ohio is one of several states under federal orders to reconfigure this tax. The good news is that Ohio can fix the tax structure in accordance with federal law. Other states have fixed their tax systems in a manner that has satisfied the requirements of the federal government. Making sure the fix does not hurt counties and transit agencies might be harder. Distribution of the local sales tax collections from the MCO revenues is based on the residence of Medicaid enrollees. A solution that cuts Medicaid MCOs from the sales tax base would hurt counties and transit agencies where many people are insured by Medicaid. Ohio must construct a solution that protects local tax bases, especially those in the most fragile economies, from another round of state-imposed cuts.[2]

What are health care provider taxes?

Federal law allows states to use revenue from taxes on health care providers to help fund the state share of Medicaid, which is jointly financed by state and the federal government. Medicaid is a form of insurance that enables people who otherwise could not afford it to get medical treatment. The federal government defines 19 forms of health services that can be subject to provider taxes, including hospital and physician services, laboratory and X-ray services, nursing homes, and intermediate care facilities for the developmentally disabled.[3] Such taxes have become an integral part of financing Medicaid, which helps a quarter of all Ohioans get health care. Every state except Alaska has at least one Medicaid provider tax and nearly two-thirds of states – including Ohio – have three or more.[4]

For every dollar in state revenue Ohio uses on Medicaid, the federal government provides, on average, almost two additional dollars. For states to get this matching money, the federal government requires that state Medicaid expenditures be supported by sources that will dependably yield the required revenues. Health care provider taxes work well for this – as long as they don’t violate federal guidelines aimed at preventing states from “gaming” the system. And that’s the problem Washington has with Ohio, among other states.[5]

Provider taxes must meet three major requirements under federal Medicaid law: They must be broad based and imposed on all health care providers within a specified class of providers; they must be uniform, or applied at the same rate for all providers that pay the tax, and they must not provide a direct or indirect guarantee that entities paying the tax get all of their payment back (in other words, the health care provider paying the tax must not be “held harmless” from the impact of the tax.) Some of these provisions may be waived under certain circumstances, but generally speaking, provider taxes need to be redistributive, with the tax redistributing funds from non-Medicaid providers to Medicaid providers.[6]

Ohio’s provider taxes

Ohio has several health provider taxes. It administers a 2.7 percent hospital franchise fee, which falls on the facility costs of non-Medicaid hospitals; a 5.5 percent fee on intermediate care facilities for the developmentally disabled and nursing homes, based on number of beds; a 1.0 percent health insuring corporation premium tax, a component of the domestic insurance tax, and the Medicaid MCO tax.[7] The federal government’s concerns are limited to the MCO tax.

Since provider taxes were first used in the 1980s, federal rules governing them have changed several times. Ohio’s Medicaid MCO tax in its current form was created in response to these changes. The Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 closed a loophole that had allowed a provider tax to apply to a very narrow base – Medicaid managed care organizations – and mandated a broad base that includes non-Medicaid providers. Ohio and a few other states solved this problem by placing the narrowly-based Medicaid MCO tax into the base of an entirely different tax that was much broader than a health care provider tax. (In Ohio’s case, it was the sales tax). Ohio’s rationale was that a broad general tax like the sales tax is not a health provider tax and not subject to Medicaid law. The federal government does not agree with that view. [8]

Ohio implemented its current MCO tax in 2009.The statute specified that this new tax would be eliminated if the federal government deemed it impermissible.[9] Although the state is not entirely in agreement with the federal government on this issue,[10] that time has come. Ohio has until June 30, 2017, to find a solution.[11] Failure to fix a violation can lead to a disqualification of state matching funds, which would reduce the amount of money the federal government gives Ohio for Medicaid.

The Fix

The 2014 letter from CMS to state Medicaid directors was quite clear, warning that use of a broad tax like the sales tax must not violate any basic health provider tax rules: it must be broad based, uniform, and hold no payer harmless from the impact of the tax.[12] Several states with taxes like Ohio’s MCO tax have crafted solutions to this mandate. Like Ohio, Michigan included its Medicaid MCOs in the state sales tax base and has worked to change it under the federal government’s directives. In the spring of 2016, Michigan’s Senate passed linked bills – SB 987-990 – that would institute a new version of the Medicaid MCO Tax with a broadened base and would eliminate another provider tax on health insurers. The distribution of funds would be changed to eliminate any possible interpretation of holding Medicaid health providers harmless from the impact of the tax. A new financing arrangement would be arranged to pay state Medicaid matching funds. The bills have not yet passed the Michigan House of Representatives, and would still have to be approved by the federal government.[13]

Pennsylvania’s 5.9 percent gross receipts tax on the Medicaid revenues of its MCOs was also found impermissible because it was not broad based (the Gross Receipts Tax does not apply to all MCOs, just to Medicaid MCOs) and because it held the Medicaid MCOs harmless.[14] The state fixed the problem by broadening the MCO assessment (known as Pennsylvania’s Gross Receipts Tax) to all entities that are MCOs as defined by Act 68 of 1998, rather than just Medicaid MCOs.[15]

California likewise fixed its MCO tax by broadening the base to include non-Medicaid providers while lowering other taxes to offset the impact. It changed the distribution of MCO tax funds to uses beyond Medicaid match alone. Established at 3.9 percent – like the state sales tax – California’s plan provides for applicable taxing “tiers” based on number of enrollees during a base year period. This does not meet the federal requirement for uniformity – by design. In the request for a waiver for this and other provisions of the law, Governor Jerry Brown wrote:[16]

“Unlike the prior versions of California's MCO taxes, this new MCO tax is broadly applied across full service health care plans and their various lines of business and not just Medi-Cal lines of business. California modeled several aspects of the MCO tax on the CMS approved California hospital provider fee.”

The waiver was approved by CMS, and the new tax started July 1, 2016.

Impact of Ohio’s MCO tax

Table 1 illustrates total MCO sales tax revenues and the Medicaid payments for services. In state fiscal year 2018, tax collections from the Medicaid MCO tax will be just over a billion dollars. The state uses $303 million to draw down federal matching funds for Medicaid services in the amount of $756 million. The net impact of the tax on the MCOs is negligible because the tax payment is calculated into the MCO capitation payment (that is, the payment for Medicaid services delivered).

Table 2 shows MCO taxes collected by state and local government (counties and transit agencies are the only local entities authorized to levy a sales tax). State funds of $303 million are used in 2018 to draw down federal matching funds for Medicaid services. The remaining $558 million dollars go in the state’s general revenue fund (GRF). Counties and transit authorities will collect an estimated $195 million dollars in fiscal year 2018 from this component of the sales tax base.

In Ohio, counties and eight transit authorities are authorized to impose a local sales tax on the state tax base. Such taxes range from a half percent to 2¼ cents. The Department of Taxation distributes collections from the Medicaid MCO tax component of the base to counties and transit authorities based on the number of Medicaid enrollees living in those places or services areas. Dependence of the local taxing jurisdiction has to do with number of enrollees and the amount of other sales tax otherwise collected.

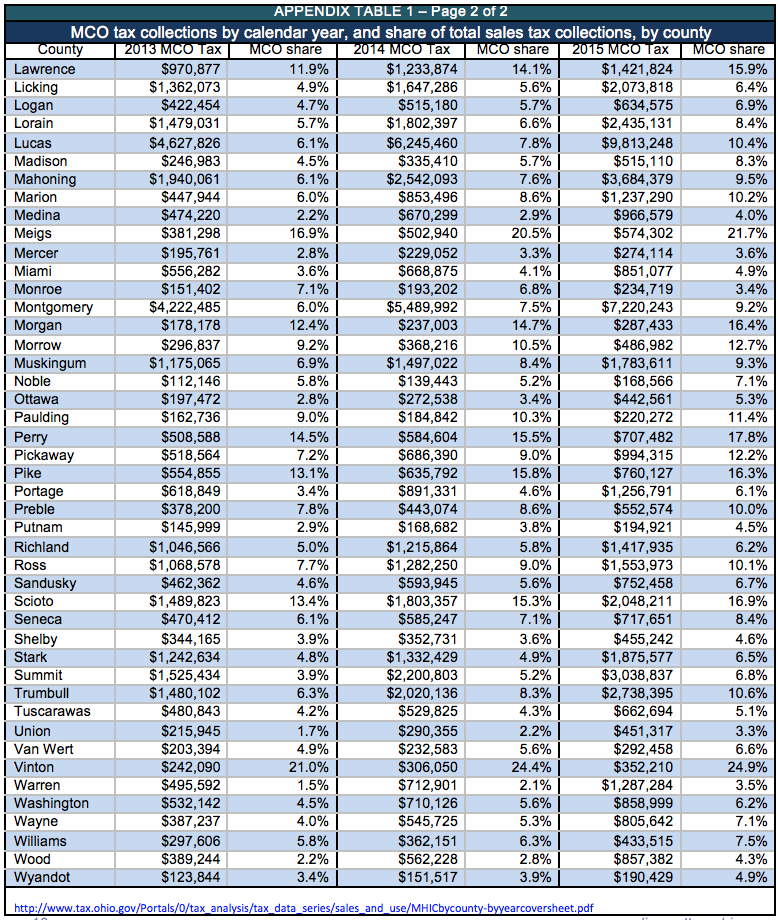

Table 3 illustrates the importance of the MCO tax in counties where the economy remains slow and many residents are enrolled in Medicaid. The largest dollar distribution is to urban counties while the highest dependence is in rural counties. The Appendix shows collections in all 88 counties in 2013, 2014 and 2015.

Counties in Ohio’s Appalachian region, some of the poorest places in the state, are the most reliant on the Medicaid MCO sales tax collections. Nearly a quarter of Vinton County’s sales tax collections come from the MCO tax. Vinton County’s general revenues totaled $4.6 million dollars in 2014[17] and of that, $306,050 – nearly 7 percent of total general fund revenues – came from the MCO tax.[18] Those funds supported county emergency or safety staff, human service personnel, road repair, fire and police vehicle operation and maintenance, and the other elements that underpin civic life.

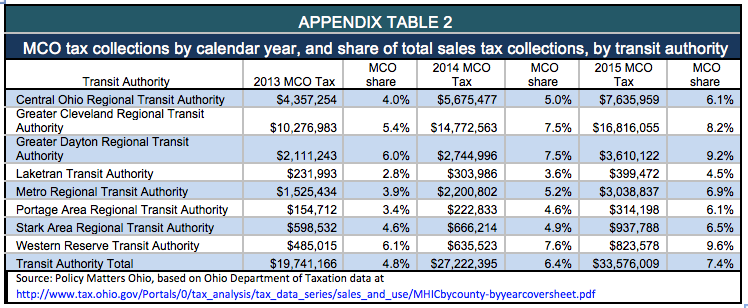

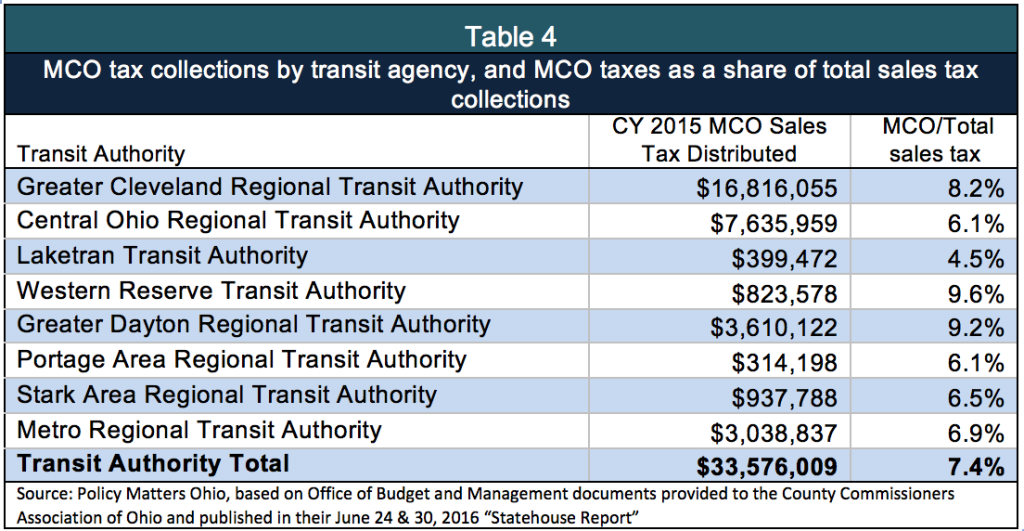

The largest impact in dollars is on urban and suburban counties. MCO tax collections are magnified here by their role in financing public transit (Table 4). Hundreds of thousands of city dwellers depend on public transit to get to work and the grocery store. Public transit has been badly cut by state government, with GRF funding falling from $42 million a year in 2000 to $15 million in 2016. Transit agencies across the state are struggling. In northeast Ohio, for example, the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (RTA) faces the loss of $18 million in revenue from the MCO tax.[19] Yet a $7 million shortfall there is already causing service cuts and fare increases.[20] Table 4 shows the 2015 MCO taxes of the eight transit authorities in Ohio. The loss of these funds would be very difficult for transit authorities and the people they serve.

Statewide, the share of the MCO revenue in the local sales tax base increased from $81 million in 2013, about 5 percent of the local sales tax base that year, to $148 million in 2015, about 7.5 percent. As enrollment increased with Medicaid expansion so has MCO tax revenue. In dollar terms, this represents growth of almost 83 percent to counties and transit authorities. Growth continues to be robust: The MCO tax is forecast to bring $195 million to these local governments in 2018 and $202 million in 2019. [21]

The problem Ohio and other states must fix in their MCO tax structure has nothing to do with the Affordable Care Act, Medicaid expansion or state Medicaid programs; it has to do with federal rules that have changed within a joint federal-state financing system, and state responses to those changes. Other states have aligned with federal requirements, ensuring solid, adequate finances for health services, and Ohio can do the same. What is different about Ohio, and critical to any solution here, is that the finances of local governments that depend on a local sales tax for important local public services must be protected from harm.

A good option would be to broaden the base of the MCO tax, but leave it within the sales tax base so it strengthens local public finance. Other provider taxes could be adjusted to mitigate impact, as in other states.

If the MCO tax is removed from the base of the sales tax, it should be recalibrated to raise funds to replace revenues in the budgets of public transit agencies and counties. This would mean boosting Ohio’s annual GRF support for public transportation from about $15 million in 2017 to about $50 million, with $35 million earmarked for the regional transit authorities. Local government fund distributions could be boosted by between $150 million and $200 million a year and distributed on the same basis as current local MCO sales tax collections, to protect county budgets.

State government needs to do more than this for local government in Ohio. The budget for 2018-19 needs to restore health and human service levies eroded by loss of tax reimbursements; boost funding for cities, villages, townships, counties and special districts that have lost, on average, 50 percent of state local government funds; and restore the estate tax on Ohio’s wealthiest estates – those over a million dollars – with most of the funds returned to the community. These state fiscal actions should remain a priority. This history of damage to local finances, however, highlights why it is essential that the solution crafted for Ohio’s MCO tax does not further damage Ohio’s communities and local public services.

Summary and conclusion

Ohio has a number of options to fix the problem identified by the federal government in its MCO tax. The tax could be applied to all managed care organizations instead of only those that provide Medicaid services, as it has been in other states. This change would not hurt the local entities that depend on Ohio’s MCO tax for non-Medicaid purposes.

However Ohio responds, there is no reason a solution to the federal problem needs to result in a cut to local revenues. Local governments have already been cut too deeply in Ohio. Ohio’s counties provide many important services in which state funding plays too small of a role. For example, Ohio ranks 50th among states in state support of children’s services, leaving poor counties struggling to protect the most vulnerable. The state budget supports adult protective services at a level far below public needs, leaving most of the provision of protective services to the counties at a time when the population is rapidly aging and more people need protection.

Since 2010, the state has cut almost a billion dollars a year in resources of local governments through cuts in revenue sharing and changes in tax policy. Any “fix” that exposes local public services to further loss is not a solution to the MCO tax problem. It just shifts the problem to localities. It is the responsibility of state government to fix the MCO tax problem in ways that bring state health care taxes into conformance with federal standards without hurting Ohioans who depend on local services. The lesson from other states is that this can be done.

[1] Capitation is a fixed amount of money per patient per unit of time paid in advance to the physician for the delivery of health care services. See American College of Physicians at https://www.acponline.org/about-acp/about-internal-medicine/career-paths/residency-career-counseling/understanding-capitation

[2] Ohio’s local governments have collectively lost a billion dollars a year, adjusted for inflation, due to cuts in state revenue sharing, elimination of the estate tax, phase-out of tax reimbursements and other tax policy changes. See Policy Matters Ohio, “New Years Budget Resolution: Commit to Opportunity,” December 2015 at http://www.policymattersohio.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/New-Years-Resolution-Commit-to-Opportunity3.pdf

[3] Community Catalyst, Health Care Provider Assessments: A State-Based Funding Solution for Closing the Coverage Gap http://www.communitycatalyst.org/resources/publications/document/ProviderAssessmentsforCTG_06.10.15.

[4] States and Medicaid Provider Taxes or Fees, Kaiser Family Foundation, March 14, 2016 at http://kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/states-and-medicaid-provider-taxes-or-fees/

[5] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Letter from Director Cindy Mann to state Medicaid Directors, June 25, 2014 at https://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/downloads/SHO-14-001.pdf

[6] California Legislative Analyst’s Office, Overview of MCO Tax, Selected Other Tax Increase Options, and IHSS Issues, July 2, 2015 at http://www.lao.ca.gov/handouts/health/2015/Overview-of-MCO-Tax-070215.pdf

[7] Information on the rates of the hospital franchise fee, the nursing facility fee and the health insuring corporation premium tax is from a memo of the Office of Budget and Management available at CCAO Statehouse Report June 30, 2016 at http://www.ccao.org/userfiles/SHR06302016.pdf

[8] The July 25 letter from Cindy Mann to State Medicaid directors, says: “Taxing a subset of health care services or providers at the same rate as a statewide sales tax, for example, does not result in equal treatment if the tax is applied specifically to a subset of health care services or providers (such as only Medicaid MCOs), since the providers or users of those health care services are being treated differently than others who are not within the specified universe.”

[9] H.B. 1, starting October 1, 2009, imposes the sales tax on health care services provided by a Medicaid health insuring corporation for Medicaid enrollees in Ohio, unless the tax is determined to be a ʺimpermissible health care‐related taxʺ for federal Medicaid purposes. The operating budget act also eliminates the tax if federal authorities determine that this expansion of the Ohio sales and use tax base is impermissible and its imposition would result in a reduction in federal financial assistance for Medicaid services. The act designates the corporations as the consumers of the services, rather than the individual receiving the services. (http://www.lsc.ohio.gov/fiscal/greenbooks128/tpr.pdf)

[10] The Ohio Office of Budget and Management wrote in a June 24, 2016 memo provided to the County Commissioners Association of Ohio: “Federal regulations that govern health care related taxes do not apply if the tax is broad based (less than 85% of the taxpayers provide or pay for health care) and individuals or entities providing or paying for health care are treated the same as other taxpayers (e.g., the same tax rate). Because the Ohio sales tax is broad based (less than 85% of the taxpayers provide or pay for health care) and the Medicaid MCOs are treated the same as other taxpayers (5.5% rate) the state’s position has been – and remains – that the Ohio sales tax is not a health care related tax and therefore not subject to federal jurisdiction."(http://www.ccao.org/userfiles/Fed%20Regulations%20may%20impact%20OH%20sales%20tax.pdf)

[11] CMS letter of June 25, 2014, cited above.

[12] CMS letter of June 25, 2014, cited above.

[13] State of Michigan, Senate fiscal office, summary of SB 987-990, May 24, 2016 at https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2015-2016/billanalysis/Senate/pdf/2015-SFA-0987-C.pdf

[14] United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General, “Pennsylvania’s gross receipts tax on managed care organizations appears to be an impermissible health care related tax,” May 2014 at https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region3/31300201.pdf

[15] Pennsylvania Health Law Project at http://www.phlp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/January-2016-HLN-Final.pdf ; see also Pennsylvania House Committee on Appropriations fiscal note on HB 1322 at http://www.legis.state.pa.us/WU01/LI/BI/FN/2015/0/HB1322P2628.pdf

[16] http://www.pwc.com/us/en/state-local-tax/newsletters/salt-insights/assets/pwc-california’s-new-managed-care-organization-tax.pdf

[17] Summarized annual financial statement, 2014, Ohio Auditor https://ohioauditor.gov/references/summarizedreports.html

[18] Ohio Department of taxation, http://www.tax.ohio.gov/Portals/0/tax_analysis/tax_data_series/sales_and_use/MHICbycounty-byyearcoversheet.pdf

[19] Ginger Christ, “RTA facing catastrophic loss in 2017,” The Plain Dealer, July 7, 2016 at http://www.cleveland.com/metro/index.ssf/2016/07/rta_facing_catastrophic_revenu.html#incart_2box

[20] Ginger Christ, “Rate increases and service cuts coming to RTA in August,” The Plain Dealer, June 7, 2016 at http://www.cleveland.com/metro/index.ssf/2016/06/fare_increases_and_service_cut.html

[21] County Commissioners Association of Ohio, Statehouse Report June 24 and June 30, 2016 at http://www.ccao.org/userfiles/SHR06302016.pdf

Tags

2016Tax PolicyWendy PattonPhoto Gallery

1 of 22