Billions in tax breaks, little accountability

February 22, 2016

Billions in tax breaks, little accountability

February 22, 2016

Contact: Wendy Patton, 614.221.4505

Executive summary

State government funds public services like schools, health and human services and universities through the operating budget or General Revenue Fund. The state also spends plenty on tax breaks for certain goods, services, industries, activities, individuals and even companies. One difference between spending through the budget and spending through the tax code is that budget items are reviewed and adjusted every two years. Spending through the tax code can last forever, without reconsideration or adjustment.

State government funds public services like schools, health and human services and universities through the operating budget or General Revenue Fund. The state also spends plenty on tax breaks for certain goods, services, industries, activities, individuals and even companies. One difference between spending through the budget and spending through the tax code is that budget items are reviewed and adjusted every two years. Spending through the tax code can last forever, without reconsideration or adjustment.Lack of oversight is a problem. The 2016-17 tax expenditure report listed 128 items that will cost the state almost $9 billion in the 2017 fiscal year. Many date back decades to when the economy and technology were far different. One dates back to 1896.

There is important momentum in the General Assembly to provide better oversight to tax expenditures. House Bill 9, which passed the House in June 2015, would create a legislative committee to review tax expenditures at least once every eight years. The committee would make a recommendation for continuation, modification or repeal of each tax break. House Bill 9 passed unanimously and has had two hearings in the Senate. Separately, House Bill 64, the budget bill for 2016 and 2017, created a committee to study and make recommendations on Ohio’s tax system. Under the bill, the new “2020 Tax Policy Study Commission” is to review and evaluate all state tax credits, among other things. There is a lot to review. This issue brief presents highlights of the 2016-17 tax expenditure report and new additions or deletions since it was published in February 2015. Tax credits are separated out for analysis.

Key findings

The tax expenditure report, published along with the governor’s executive budget proposal, lists 128 tax expenditures in 2016-17. The Ohio Department of Taxation forecasts that the value of revenues foregone will be $8.5 billion in 2016 and $8.9 billion in 2017.

Other important findings include:

- Ohio spends as much on tax expenditures as it spends in the General Revenue Fund (the state operating budget) on K-12 education.

- Tax expenditure reports are submitted with the executive budget proposal. Revenues foregone as a result of tax expenditures in the 2016-17 report grew by $1.3 billion (8.3 percent) compared to the 2014-15 tax expenditure report.

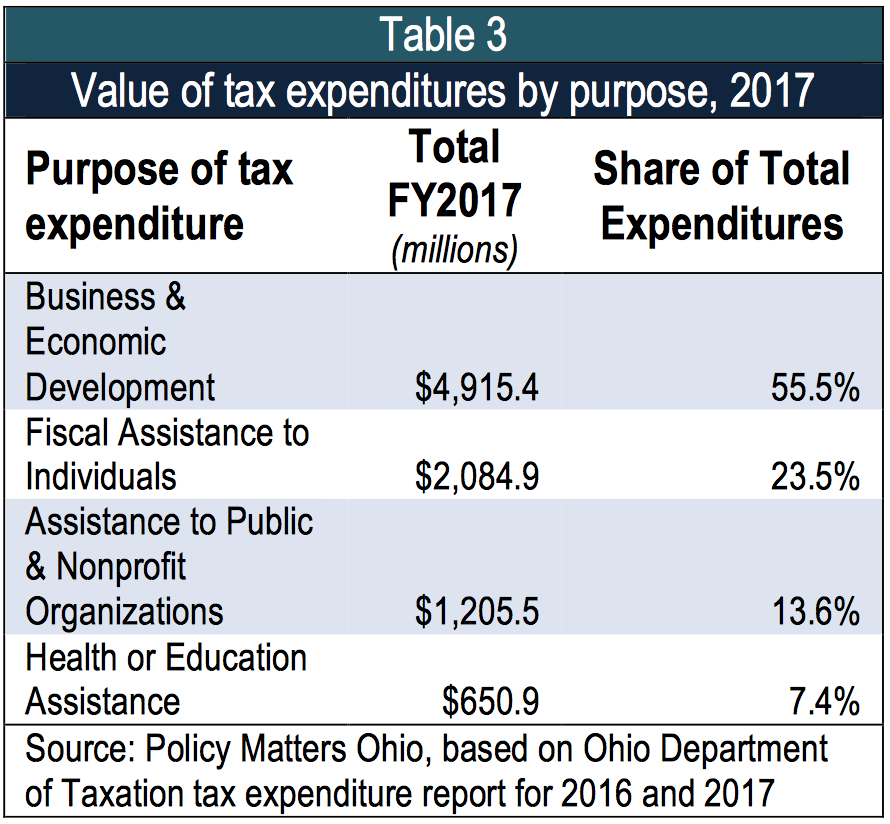

- More than half of the value of all tax expenditures – $4.9 billion in 2017 – goes to business and economic development. About a quarter provides fiscal assistance to individuals, mostly through the income tax.

- Sales tax expenditures account for the largest share. There are 56 tax breaks in the sales and use tax, adding up to $5.6 billion in 2016, two-thirds of total revenues foregone.

- The sales tax exemption for property used in manufacturing is by far the largest overall tax expenditure, as it has been for many years. With expected foregone revenue of $1.89 billion in 2016, it is almost triple the size of the second-largest tax expenditure, the sales tax exemption for sales to churches and other nonprofits.

- The so-called “small business” investor income tax deduction, created in the 2014-15 budget, was initially forecast to cost $327.2 million in 2017 – before it was expanded in the budget bill and subsequently in Senate Bill 208. In just its fifth year, it likely would become the second-largest tax expenditure, based on data in the report and estimates of expansion costs.

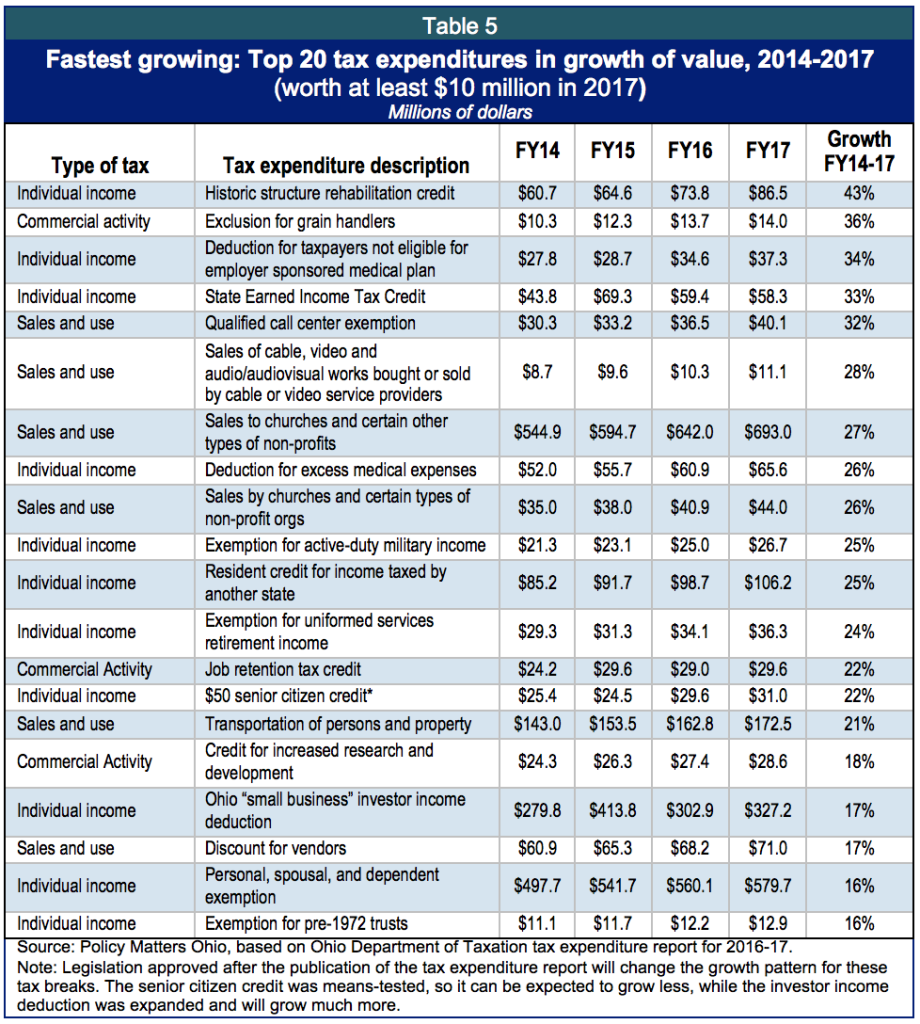

- The historic structure rehabilitation tax credit grows the fastest of all tax breaks over $10 million in value. The 2020 Tax Policy Study Commission was specifically charged with reviewing this particular tax credit.

Governors – including Gov. Kasich – have proposed eliminating or limiting many tax expenditures. The legislature has ignored many of his proposals. At the same time, at any given time, many new tax breaks are under consideration in the general assembly, which takes more readily to spending through the tax code than on the budget side of the ledger.

House Bill 9 and the review of tax credits by the 2020 Tax Policy Study Commission create the potential to improve, update and make our tax system more efficient and equitable.

Introduction

Ohio lawmakers have increased spending on tax breaks, but fiscal oversight of billions of dollars in these tax exemptions, credits and deductions is lacking.These “tax expenditures” will total almost $9 billion in the 2017 fiscal year. The tax breaks apply to certain goods and services, industries, activities, individuals and companies. They make up a significant share of overall state spending, but they are not regularly reviewed.

Unlike budget spending on public services such as parks, schools and universities – which are reviewed regularly – tax expenditures remain in law indefinitely unless there is a pre-existing termination date.

Legislators pass a new budget every two years in Ohio and they review expenditures and make corrections in between. Although the state is required to report on tax breaks, legislators are not required to review and adjust them. The 2016-17 tax expenditure report listed 128 items that account for the aforementioned $9 billion. Many date back decades to when the economy and technology were far different. One dates back to 1896.

While the Ohio General Assembly has ignored proposals from Gov. John Kasich to eliminate some tax breaks, there is momentum among lawmakers to provide better oversight. House Bill 9, which passed the House in June 2015, would create a legislative committee to review tax expenditures at least once every eight years. The committee would make a recommendation for continuation, modification or repeal of each tax break. House Bill 9 passed unanimously and has had two hearings in the Senate. Separately, House Bill 64, the budget bill for 2016 and 2017,[1] created a committee to study and make recommendations on Ohio’s tax system. Under the bill, the new “2020 Tax Policy Study Commission” is to review and evaluate all state tax credits, among other things. There is a lot to review. This issue brief presents highlights of the 2016-17 tax expenditure report, as well as changes since it was published in February 2015. Tax credits are separated out for analysis.

Key findings include:

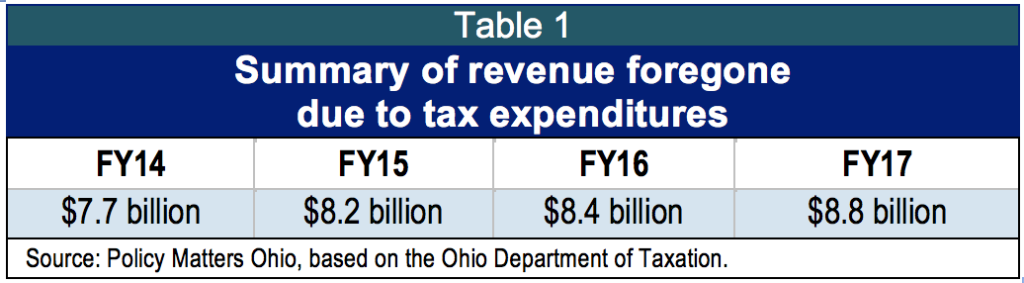

- The tax expenditure report, published along with the governor’s executive budget proposal, lists 128 tax expenditures in 2016-17. The Ohio Department of Taxation forecasts that the value of revenues foregone will be $8.5 billion in 2016 and $8.9 billion in 2017 (Table 1).[2]

- Tax expenditures grow by $1.3 billion (8.3 percent) in 2016-2017 compared to the prior two-year budget period.

- More than half of all tax expenditures – 55.5 percent of the total value or $4.9 billion in 2017— goes to business and economic development.

- Sales and use tax[3] expenditures account for the largest share. There are 56 sales tax breaks, adding up to $5.6 billion in 2016, or 66 percent of the total.

- The sales tax exemption for property used in manufacturing is by far the largest overall tax expenditure, as it has been for many years. With expected foregone revenue of $1.89 billion in 2016, it is almost triple the size of the second-largest tax expenditure, the sales tax exemption for sales to churches and other nonprofits.

- The so-called “small business” investor income tax deduction, created in the 2014-15 budget, was initially forecast to cost $327.2 million in 2017 – before it was expanded in the budget bill and subsequently in Senate Bill 208. In just its fifth year, it likely would become the second-largest tax expenditure, based on data in the report and estimates of expansion costs.

- The historic structure rehabilitation tax credit grows the fastest of all tax breaks over $10 million in value. The 2020 Tax Policy Study Commission was specifically charged with reviewing this particular tax credit.

The Tax Expenditure report highlights how spending through the tax code is similar to budgetary spending: “Both tax expenditures and direct budgetary expenditures result in a cost to the state,” the report points out, but goes on to say, “Unlike direct budgetary expenditures, unless there is a pre-existing termination date, tax expenditures may remain in law indefinitely.”[4]

Tax expenditures have a high cost in foregone revenue and many offer questionable benefits. Gov. Kasich has recommended repealing a number of tax exemptions in his executive budget proposals and has vetoed numerous tax breaks tucked into budget bills. In the executive budget last year, Gov. Kasich proposed limiting or repealing a variety of tax breaks that were not accepted by the General Assembly. For instance, he proposed:

- Eliminating the tax credit and discount that sellers of beer, wine and mixed beverages get for paying their alcoholic beverage tax a few weeks in advance;

- Limiting the amounts retailers can receive for collecting the sales tax, known as the vendor discount. Most states either have no discount at all or cap the amount, ensuring that big retailers do not reap a windfall. Indeed, Tax Commissioner Joe Testa said in testimony that Ohio’s 0.75 percent discount “essentially functions as a profit center” for big-volume retailers.

- Cutting the sales-tax exemption for trade-ins of used cars and boats in half, and

- Repealing the 2.5 percent discount that distributors of cigars, chewing tobacco and other tobacco products get for timely payment of their taxes. “It shouldn’t be necessary to reward businesses for paying their tax on time,” as Testa noted.[5]

Those are hardly the only tax expenditures in need of limitation or repeal. The state offers a write-off against the commercial activity tax, the state’s main business tax, for losses that big companies experienced before the tax was enacted, even though they no longer pay taxes on their income; a sales-tax exemption worth more than $27 million a year for pollution-control equipment purchased by utilities, even though most of it is mandated; and a cap on sales tax for wealthy buyers of shares in jet aircraft, who pay only a fraction of the tax they would otherwise.

Spending through the tax code

Tax exemptions, deductions, and credits all can reduce the amount of taxes that a taxpayer – be it a company or a person – owes.

- A tax exemption allows a taxpayer to not pay a certain tax. For example, purchases of not-for-profit organizations and churches are exempt from the sales tax. Many items businesses purchase for use in producing goods and services are exempted from the sales tax.

- A tax deduction is an expense that is subtracted from total income when calculating taxable income.

- A tax credit is the direct dollar-for-dollar reduction of tax liability. For example, the job creation tax credit is taken against a company’s commercial activity tax. The earned income tax credit is taken against the individual income tax. If the tax credit is refundable, individuals or companies can receive its full amount whether or not they have any tax to offset.

- The item reduces or could reduce one of the taxes that support the state's General Revenue Fund, Ohio’s main operating budget. Local taxes, or those that do not fund the revenue fund (like the motor vehicle fuel tax, horse racing tax, and the severance tax) are not included in the tax expenditure report.

- The item would have been part of the defined tax base. For a provision to be a tax expenditure, it must exempt from taxation a person or activity that otherwise would have been part of the tax base. The sales tax, for instance, is defined to cover tangible goods. Only specifically enumerated services are covered, so many others, such as hospital services, are not a part of the defined tax base and are not included as tax expenditures in the report.

- The item is not subject to an alternative tax. Persons or activities subject to alternative taxes are not considered tax expenditures in the report. For example, insurance companies are excluded from the commercial activity tax under the Ohio Revised Code, but this exclusion is not considered a tax expenditure because insurance companies are taxed under insurance premium taxes.

- The item is subject to change by state legislative action. The item must take the form of an exemption, deduction, credit, etc., existing in the Ohio Revised Code. Anything that can be changed purely by a state constitutional amendment, a federal law change, or a federal constitutional amendment is not considered a tax expenditure in the report. Thus, the state constitution’s prohibition on charging sales tax for food consumed off the premises is not included in the report.

Tax expenditures by type and category

Tax expenditures by type and categoryThe Ohio Department of Taxation forecasts tax expenditures of $8.5 billion in 2016 and $8.9 billion in 2017, $1.3 billion (8.3 percent) higher than in the prior two-year budget period for 2014-15. The annual amount is about one-third as large as all of the state dollars in the state’s operating budget (the General Revenue Fund).[7] Ohio spends as much on tax breaks as we do on primary and secondary education. According to the Legislative Service Commission, Ohio will spend $8.6 billion state source dollars for K-12 education in 2016 and $9 billion in 2017, closely mirroring value of revenues foregone to tax expenditures over the same period.

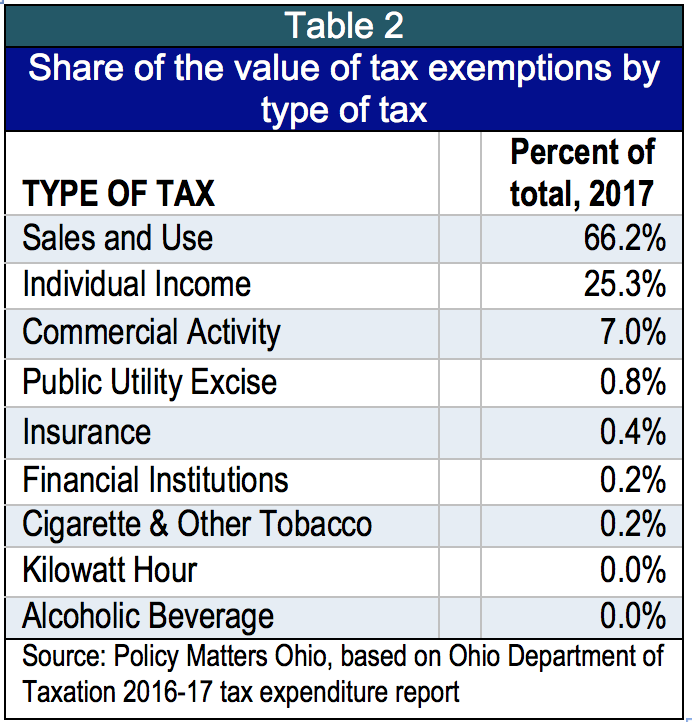

Tax expenditures taken against the state’s sales and use tax made up two-thirds of the total cost of all tax breaks, at more than $5.5 billion a year (Table 2). Sales tax breaks alone are greater than state share of Medicaid spending, which provides health care to a quarter of all people in the state.

The next largest category of tax expenditure includes those applied against the individual income tax. At about $2 billion annually, this category accounts for a quarter of revenues foregone to tax expenditure. This is more than state dollars spent on all human services other than Medicaid, including (but not limited to) community services for the addicted and mentally ill, protective services for children and seniors, cash assistance safety net programs and funding for food banks.

The third largest category consists of tax expenditures taken against the commercial activity tax, the broad tax on business activities. The tax will forgo about $600 million in each year of Ohio’s new two-year budget because of tax breaks. Just half of this amount would restore need-based financial aid for college students to pre-recession levels on an inflation-adjusted basis.[8]

Overall, the share of the value of tax exemptions by type of tax was virtually unchanged between 2014 and 2017.

Overall, the share of the value of tax exemptions by type of tax was virtually unchanged between 2014 and 2017.

In its 2009 report, the Taxation Department broke out tax expenditures by broad purpose. It discontinued doing so, but Policy Matters Ohio used the same categories earlier employed by the department to provide such a breakdown. Tax expenditures for business and economic development make up 56 percent of total cost (Table 3). The next largest category, fiscal assistance for individuals (like the joint filer credit taken against the personal income tax) is less than half of that. About 13 percent of total tax expenditures benefit state and local governments, churches and non-profit organizations. About 7 percent provide benefits related to health and/or education (exemptions of Pell grants or dislocated worker training benefits from income taxes or deductions for certain medical benefit situations).

Largest and fastest-growing

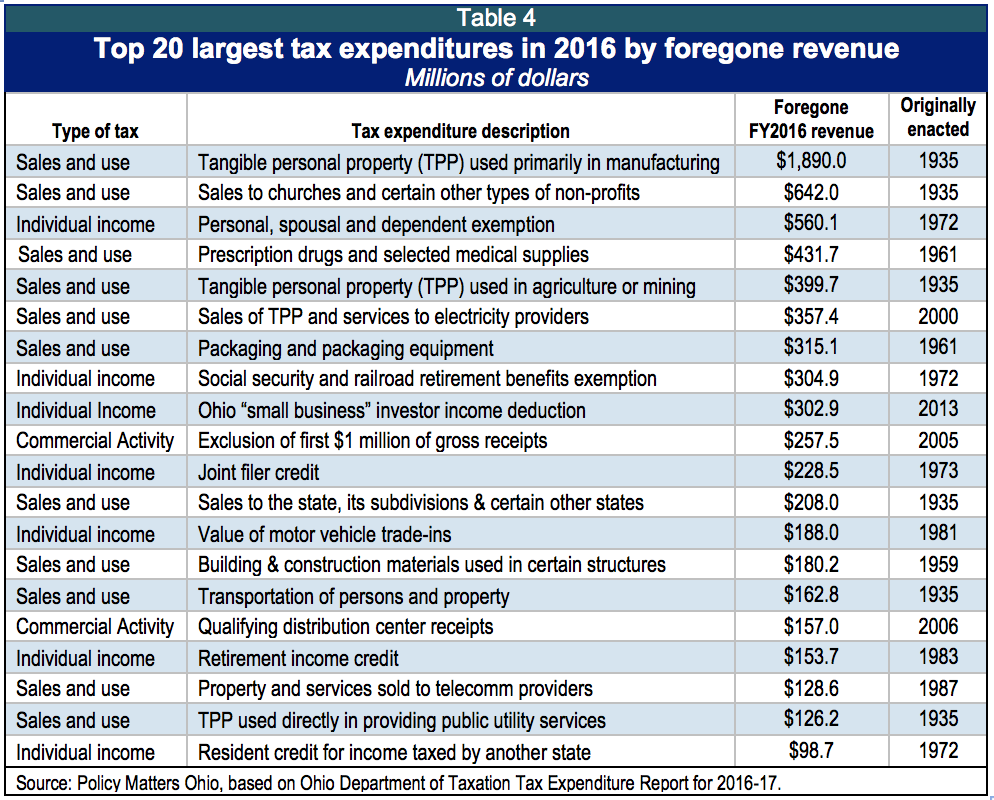

Table 4 lists the 20 largest tax expenditures in the tax expenditure report for 2016-17. These tax breaks, the smallest of which is just under $100 million a year, account for 83 percent of total tax expenditures in the state. Overall, this list is very similar to the list from the previous biennium. All but one of the tax expenditures were among the top 20 in the 2014-15 tax expenditure report.

- The sales and use tax exemption for property used primarily in manufacturing is by far the largest overall tax expenditure, as it was in the previous report. With expected foregone revenue of $1.89 billion in 2016, it is almost triple the size of the second-largest tax expenditure, the sales tax exemption for sales to churches and other nonprofits.

- The “small business” investor income tax deduction, forecast in the report to cost $327.2 million in 2017, is the only new addition to the list since the last tax expenditure report. Since the publication of the report, this tax break was further expanded. It is worth noting here that although the tax department calls this a “small business” deduction, it is most useful for high-income earners who are investors in partnerships or other businesses that report profits on their personal income-tax returns, and benefits owners of businesses both large and small. In fact, calendar year 2015 data show that although only 8 percent of claimants took deductions of $100,000 or more, they got almost half (47 percent) of the hundreds of millions of dollars in this tax break.[9]

- The historic structure rehabilitation tax credit is expected to grow the fastest among the 20 tax expenditures listed on Table 5. This tax credit was specifically identified in House Bill 64 for review by the 2020 Tax Policy Study Commission, which is to figure out: how to make the tax credit more efficient and effective, including converting it to a refundable tax credit or grant program.[10]

- The new and fast-growing exemption for grain handlers is based on the idea that for-profit grain handlers need it to compete with nonprofit grain handlers, which aren’t subject to the commercial activity tax. It was opposed by the Ohio Manufacturers’ Association, whose representative noted in testimony to the Senate Ways and Means Committee that, “All for-profit enterprises should be paying the CAT; in fact, equality in the burden of taxation demands that they all remain subject to the tax.”[11]

- The growth rate of the income-tax deduction for taxpayers not eligible for employer-sponsored medical plan reflects several factors, including the interaction of other credits and deductions for medical expenses and medical insurance and federal estimates of the cost of health care spending.[12]

- Five of the state’s largest tax expenditures join some smaller tax expenditures that, because of their small size, show very high growth in Table 8.

- Sales to churches and other non-profits: Seventh on the list of tax breaks with fast growth, this one is forecast to grow by 27 percent between 2014 and 2017.

- Resident credit for income taxed by other states: Eleventh on the list of fastest growing, with a growth rate of 25 percent between 2014 and 2017.

- Transportation of persons and property: This tax break against the sales tax ranks 15th with growth of 21 percent between 2014 and 2017.

- Individual exemptions: The individual income tax’s “personal, spousal, and dependent exemption” ranks 19th out of 20 with a growth rate of 16 percent. This exemption was increased for taxpayers with income of $80,000 and below starting in tax year 2014, driving the growth rate.

The number of tax expenditures has been essentially stable over three two-year budget periods. In the current budget period, 128 tax exemptions are listed in the tax expenditure report.[13]

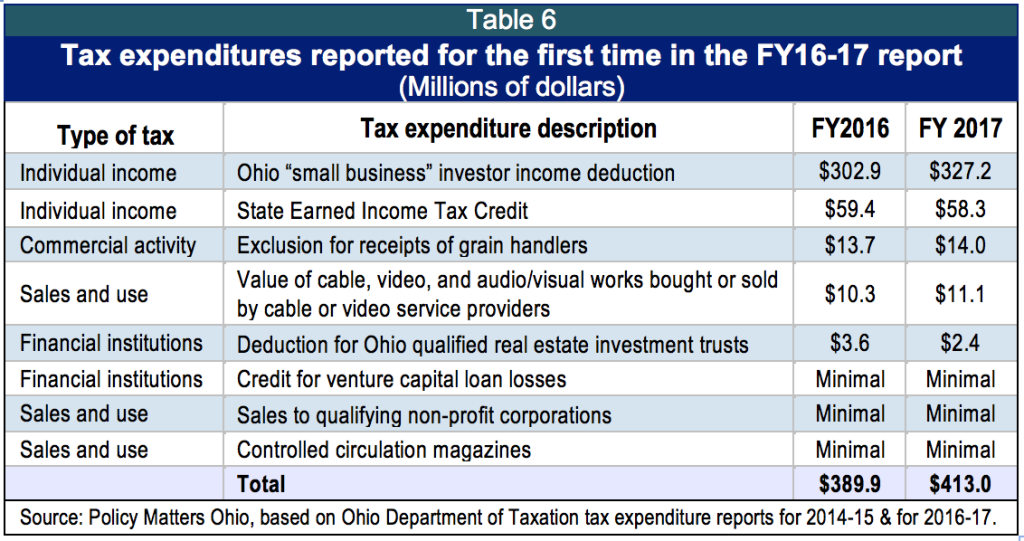

Most of the items in Table 6 – “new tax expenditures” – were created during the spring of 2013 in the course of budget deliberations for House Bill 59, the budget bill for 2014-15.[14] The last tax expenditure report was issued in January 2013, before those deliberations began. At that time, these tax expenditures had been neither introduced nor passed. While they were in place in 2014 and 2015, they are reported on for the first time in the most recent tax expenditure report, for 2016-17.

- The “small business” investor income tax deduction was new in 2014 and 2015. It has been greatly expanded since the latest tax expenditure report and is rapidly becoming one of the state’s largest tax expenditures (see discussion below about tax expenditures and expansions approved since the budget bill for 2016-17 passed.).

- The earned income tax credit (EITC) helps low-income working families with children. A federal tax credit that 26 states also provide, this is considered the nation’s most powerful anti-poverty program. Ohio implemented a 5 percent EITC coupled[15] to the federal credit in the 2014-15 budget bill and expanded it to 10 percent in subsequent legislation. Ohio’s EITC is very small because it is not refundable and is capped at the first $20,000 of taxable income.

- The exclusion for grain handlers, described above in the section on the fastest growing tax expenditures (Table 5), was new since the last tax expenditure report and shows up for the first time in the 2016-17 tax expenditure report.

- The value of cable, video, and audio/visual works (“digital products”) bought or sold by cable or video service providers will be exempted from the sales and use tax. These transactions were excluded from the definition of “telecommunications services” going into budget deliberations of House Bill 59, the budget bill for 2014-15. While the definition of “telecommunications services” changed in House Bill 59 and the sales tax was extended to digital products, these items continued to be excluded. Because they now represent a specific tax break from the new base, they are reported on for the first time in the 2016-17 tax expenditure report.[16]

- The credit for venture capital loan loss is not new, but it is reported on for the first time in the 2016-17 tax expenditure report. Fiscal impact of the tax credit was not identified in prior program years.[17]

- The deduction for investments in an Ohio qualified Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) from the financial institutions tax (FIT) was created as a part of the phase-in of that tax in 2013. The phase-in will be completed and the deduction eliminated after 2017.[18]

- The cryptically designated “sales to qualifying non-profit corporations” is actually a tax break specific to the not-for-profit entity that owns the Toledo Mud Hens. This tax expenditure wiped out a sales tax bill that had accrued over prior years and amounted to about a half million dollars.[19]

- While the tax break for magazine subscriptions was repealed in the 2013 budget bill, a small exemption for controlled circulation magazines was retained; the residual shows up as a “new” exemption in the 2016-17 tax expenditure report.[20]

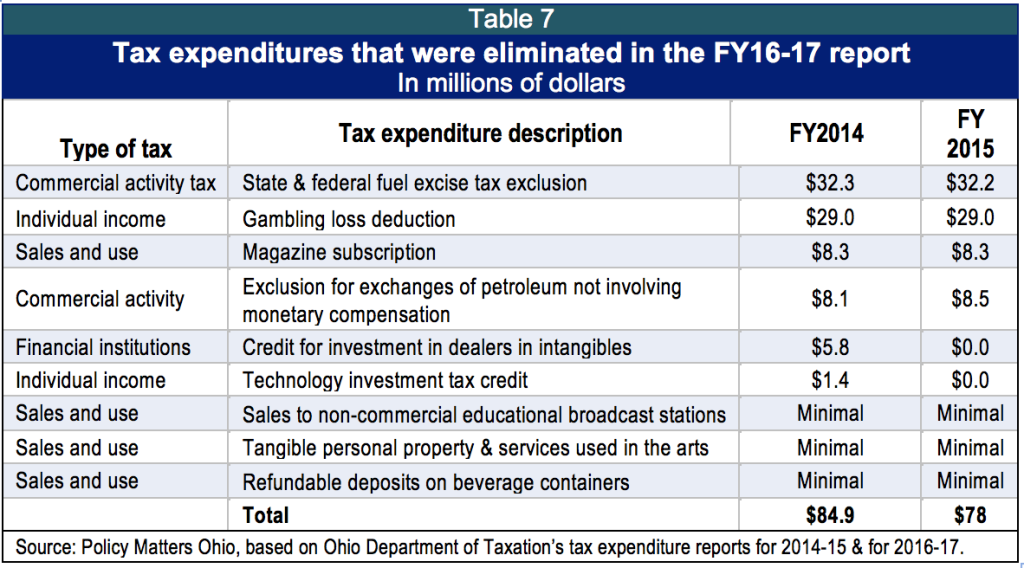

- The state and federal fuel excise tax exclusion and the exclusion for exchanges of petroleum not involving monetary compensation were eliminated when motor fuel receipts were eliminated from the base of the commercial activity tax and moved to the petroleum activity tax, where they were incorporated into the definition of the base.[21] They are therefore no longer a tax expenditure.[22]

- The gambling loss deduction was eliminated in the budget bill for 2014-15.[23]

- The tax exemption for subscription magazines was repealed, although as noted above, a small exclusion for “controlled circulation” magazines, with minimal cost, continues.

- The “dealers in intangibles tax” was eliminated in 2014. House Bill 510, which created the financial institutions tax, created a one-year nonrefundable credit for residual dealers in intangibles taxes against the financial institutions tax, effective for 2014 only.[24]

- The technology investment credit was repealed in the 2013 budget bill.[25]

- The sales tax exemption for sales to non-commercial educational broadcast stations is now grouped with “sales to churches and certain nonprofit organizations.” In other words, the tax expenditure still exists but is accounted for differently.[26]

- The sales tax exemption for tangible personal property and services used in the arts is also now grouped with “sales to churches and certain nonprofit organizations.”[27]

- The credit for refundable deposits on beverage containers is eliminated through Ohio’s conformance to the streamlined sales and use tax agreement, which was established in House Bill 95, the budget bill passed by the 125th General Assembly.[28] The agreement includes in its definition of "price" money received as a deposit refundable to a consumer upon return of a beverage container or a carton or case used for returnable containers. [29]

The executive budget proposal starts the budget deliberations off, but what comes out and is signed by July 1 often looks different from the initial proposal. A process, including numerous public hearings and testimony by administration officials, allows for a discussion of state spending. By contrast, though state law requires the governor to include a tax expenditure report with the executive budget proposal, there is no further requirement that the report be used in any way, or that any regular review of such expenditures take place. Even tiny line items are at least open to scrutiny and debate; tax expenditures come up only if the governor or legislators specifically seek new ones or change in existing ones. Most of the tax breaks that have been eliminated have vanished because an entire tax has gone away, not through review or reconsideration.[30]

Additional tax breaks were added or increased during last year’s budget proceedings. One significantly expanded one of the largest tax expenditures in the tax code. Others were much smaller, totaling less than $15 million. Tax breaks added in this budget process, after the tax expenditure report was published, included the following:[31]

- Largest of the budget bill: The so-called “small business” investor income tax deduction is an expanded deduction for income of owners of pass-through entities – businesses such as partnerships and S Corporations, limited liability corporations and sole proprietorships – who pay personal income tax on their profits. This deduction ranked among the largest tax breaks, costing the state an estimated $327.2 million in 2017. However, the Kasich administration estimated the cost of the legislature’s expansion of that tax break will amount to another $558 million that year.[32] . For its part, the Legislative Service Commission (LSC) pegged the cost in 2017 at $490 million.[33] While the exact cost of the deduction won’t be known for some time, it likely will become the second-largest tax expenditure in Ohio law.

- “Beauty break”: A break on the commercial activity tax for companies located in a suburban Columbus business park that are in the same supply chain making “a personal care, health, or beauty product or an aromatic product, including a candle.”

- A break for compliance: A sales-tax exemption covering federally required sanitation services provided to meat slaughtering or processing operations.

- A break for auto insurers: One of the sales-tax exemptions covers rental vehicles that car dealers provide while repairing customer vehicles, if the cost of the rental vehicle is being reimbursed. (Gov. Kasich vetoed a similar exemption in another bill earlier in 2015)[34]

- A change in tax for certain farm lenders, production credit associations and agricultural credit associations, which are to be taxed under the commercial activity tax instead of the financial institutions tax.

Beyond the budget itself – new tax breaks enacted over the fall

Few entirely new tax expenditures have been enacted since the last budget bill. One was a provision reducing the commercial activity tax for railways’ purchases of dyed diesel fuel. This compensates railway companies for the additional tax that arises because of the newly created petroleum activity tax, so they effectively pay the lower CAT rate on purchases of such fuel. The taxation department did a fiscal analysis of House Bill 340, which included this change, and estimated the revenue loss as minimal in 2016 and $1.5 million in all state funds in 2017.[36]

The General Assembly also has made changes to existing tax expenditures since the publication of the biennial report. For example, Senate Bill 208 approved last fall removes limitations on the personal exemption and a number of income-tax credits so they can be applied whether taxpayers’ income is from business or non-business sources. The Legislative Service Commission estimated the cost of these changes at between $2 million and $8 million a year. This review does not attempt to cover all such changes made since the tax expenditure report was published.

2020 Tax Policy Commission to look at tax credits

As noted, House Bill 64, the budget bill for fiscal years 2016-17, created the 2020 Tax Policy Study Commission, which has started its review of Ohio’s tax structure. Among other things, the commission was charged with scrutiny of all tax credits.

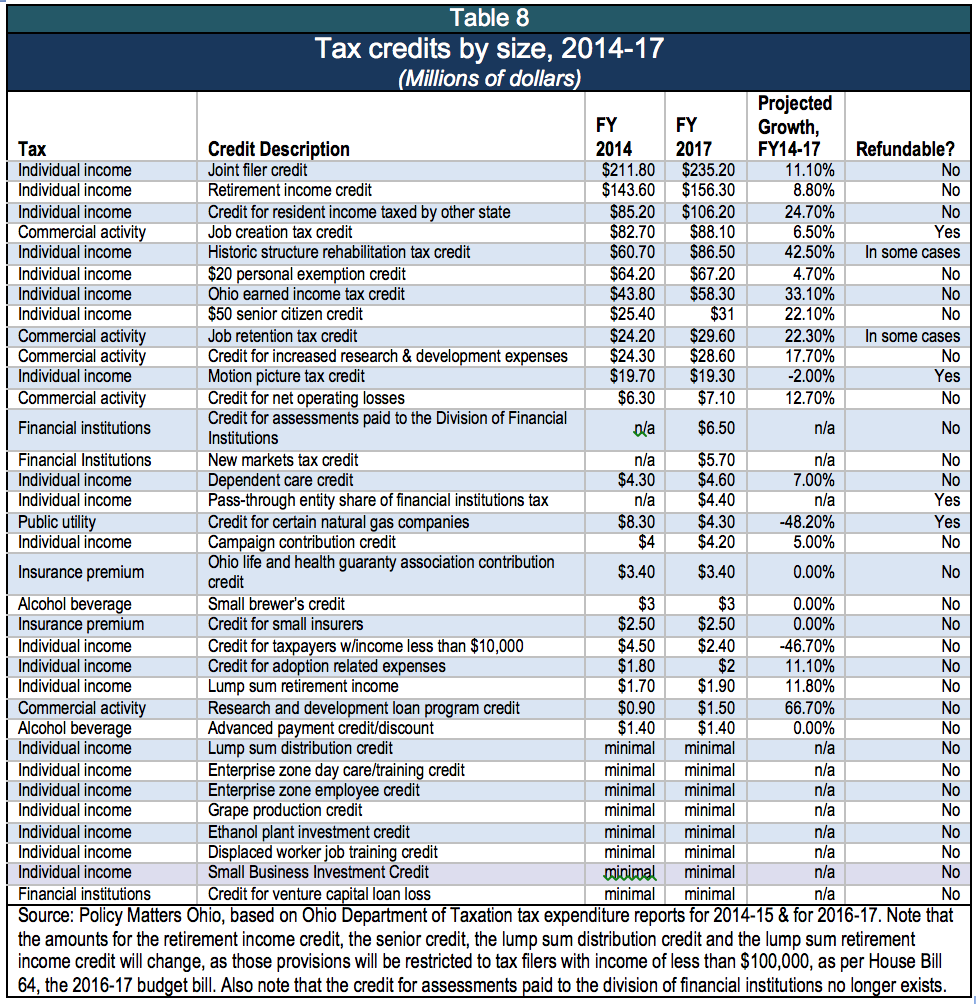

Out of the 128 expenditures in the last tax expenditure report, 34 are tax credits worth $928 million in fiscal year 2016 and $961 million in fiscal year 2017. About a third benefit individuals like the retirement income exemption,[37] the earned income tax credit, the $20 personal exemption and the credit for income taxes by another state. Twenty-one of 34 are credits for business (job creation tax credit; enterprise zone day care credit) or real estate development (historic preservation tax credit).

Table 8 shows the Ohio tax credits with more than minimal value in 2017 ranked by size. The three largest include the joint filer credit, the retirement income credit[38] and the credit for income taxed by another state. Just these three account for more than half the total value of tax credits.

Table 8 also shows that six of the tax credits are refundable: in other words, when the value of the tax credit is greater than the tax liability, the state refunds the difference. These tax credits are for businesses and include the motion picture tax credit, the tax credit for pass-through entities paying the financial institution tax; the job creation tax credit and the tax credit against the public utility tax listed below. Two more are refundable in part (historic preservation tax credit) or under certain circumstances (job retention tax credit).

Table 8 also shows that six of the tax credits are refundable: in other words, when the value of the tax credit is greater than the tax liability, the state refunds the difference. These tax credits are for businesses and include the motion picture tax credit, the tax credit for pass-through entities paying the financial institution tax; the job creation tax credit and the tax credit against the public utility tax listed below. Two more are refundable in part (historic preservation tax credit) or under certain circumstances (job retention tax credit).

Table 8 also gives the rate of growth between 2014 and 2017 for tax credits. Small tax expenditures show the fastest growth, a function of size. For instance; the new markets tax credit was created in 2009 and FY 2015 was the first year in which could be claimed, so it’s not surprising that it leads the list in growth. However, seven of the fastest growth tax credits, with a growth rate of greater than 10 percent between 2014 and 2017, are also among the 10 largest.

- The joint filer credit, the largest tax credit among the fast growers, increases by 11 percent and makes it to the list of the top dozen tax credits in growth.

- The historic structure rehabilitation tax credit, discussed above, is one of the largest tax credits. The program itself is capped at $60 million a year in tax credits it can give out, but this does not correlate precisely with the timing of claims.

- The earned income tax credit, created in the budget bill for 2014-15, was doubled from 5 percent of the federal credit to 10 percent in the mid-biennium review of 2014, driving the growth in the this tax expenditure.

- The credit for resident income taxed by other states grows from $85.2 million in 2014 to $106.2 million in 2017, an increase of almost 25 percent.

- The credit for assessment to the division of financial institutions was repealed by House Bill 340, passed in December 2015. This bill eliminated the regulatory assessments imposed on certain financial institutions by the Division of Financial Institutions to fund the division's operations, and repealed the tax credit allowed to those institutions for the payment of those assessments. [39]

In June 2015, the 131st General Assembly passed House Bill 9 to create a process to review tax expenditures. The bill had 60 sponsors from both sides of the aisle, passed unanimously, and has since has received two hearings in the Senate Ways and Means Committee.

The bill would create a permanent, bi-partisan joint committee of six legislators and the tax commissioner (or designee) to periodically review all existing tax expenditures and make recommendations to the General Assembly about continuation, modification, or repeal of existing ones. It would require any bill proposing a new or modified tax expenditure to include a statement of the objectives and intent of the tax expenditure for use in the review process.

It also puts into statute the basic criteria used in the state tax expenditure report to determine whether a tax provision constitutes an Ohio tax expenditure.

The bill specifies that the committee will meet in the first year of the fiscal biennium (once every two years during the year the budget is passed) and must provide for hearings. Each tax expenditure must be reviewed at least once every eight years. Each item reviewed must be recommended for continuation, repeal or modification, and the committee may impose accountability standards on an item to be considered in future reviews.

The legislation outlines factors the committee may consider in its review. They include the number and classes of those who benefit, the fiscal impact on the state and localities, and public policy objectives that might support the tax expenditure, such as whether it supports business growth, high-wage jobs and community stabilization. Among the other factors are whether it creates an unfair business advantage or unintended benefits, what the effects would be of terminating it, or if its objectives could be accomplished without it or through legislative appropriations.

This bill provides a badly needed oversight structure to a growing body of un-scrutinized public expenditures. The bill would have a more significant impact if it included automatic sunsets for tax expenditures, so they expired unless the General Assembly reauthorized them. The worth of each expenditure should be proven. In addition, the Legislative Service Commission should be given the resources to do a thorough study of each tax expenditure prior to its examination by the review committee. The governor, who under the bill must include the review committee’s most recent report in the budget proposal, should also recommend whether any recently evaluated tax expenditures should be continued, modified, or terminated. And Ohio should expand its tax expenditure report to improve disclosure.[40]

Summary and conclusion

Tax expenditures make up a significant share of overall state spending, but they are not regularly reviewed. Many date back decades. Are they still economically useful?

Governors – including Gov. Kasich – have proposed eliminating many tax expenditures. The legislature has ignored most of his proposals. At the same time, at any given time, many new tax breaks are under consideration in the general assembly, which takes more readily to spending through the tax code than on the budget side of the ledger.

House Bill 9 and the review of tax credits by the 2020 Tax Policy Study Commission create the potential to improve, update and make our tax system more efficient and equitable.

[1] All years referenced in this report refer to a state fiscal year, July 1 to June 30, unless otherwise noted.

[2] The report estimates foregone revenue, which is not necessarily what the state would take in if a tax expenditure were repealed. The revenue estimates in the report reflect “General Revenue Fund revenue foregone,” or benefits to recipients of credits and exemptions. The taxation department notes in bold-faced type that “the figures in this report do not represent the estimated revenue gain from the repeal of the tax expenditure.” (p.4) There may be a time lag before the full effect of repealing the tax expenditure shows up in revenues, not all taxpayers may immediately comply with the change, or taxpayers could behave differently because of the change. See Tax Expenditure Report, op. cit., pp. 3-4. In testimony to the Senate Ways & Means Committee, then Deputy Tax Commissioner Frederick Church said the report’s estimates are “close to, but not exactly equal to, expected revenue gains from repeal of expenditures.” Frederick Church, Presentation to Senate Ways and Means and Economic Development Committee, Nov. 17, 2011.

[3] Use tax is a complementary tax to the sales tax, covering purchases made outside the state for use in Ohio. We include it with the sales tax throughout this report.

[4] Ohio Department of Taxation, Tax Expenditure Report, State of Ohio Executive Budget for Fiscal Years 2016-17, Ohio Office of Budget and Management at http://obm.ohio.gov/budget/operating/doc/fy-16-17/State_of_Ohio_Budget_Tax_Expenditure_Report_FY-16-17.pdf

[5] Joe Testa, Tax Commissioner, Testimony to the Senate Ways & Means Committee, April 29, 2015, at http://ohiosenate.gov/committee/ways-and-means#

[6] These four items are taken from the Ohio Department of Taxation’s tax expenditure report for 2016-17.

[7] State-source spending in the General Revenue Fund (GRF) budget will be $22.6 billion in 2016 and $23.4 billion in 2017.State-source GRF funds do not include the federal dollars (primarily Medicaid dollars) that Ohio – unlike other states – also puts into its GRF.

[8] Ohio invests $309 million less in need-based financial aid now than in the budget for 2008-09. See Wendy Patton and Hannah Halbert, “State support for higher education is still behind the curve,” Policy Matters Ohio, December 23, 2015 at http://www.policymattersohio.org/highered-dec2015

[9] Policy Matters Ohio calculation from Ohio Virtual Tax Academy webinar presentation by Deborah Smith, Administrator, Personal & School District Income Tax Division, Ohio Department of Taxation, “Personal and School District Income Tax Business Income Deduction & Tax Calculation,” Dec. 16, 2015, at http://www.tax.ohio.gov/Researcher/VTA/Archive/December2015.aspx#Debbie

[10] House Bill 64 of Ohio’s 131st General Assembly, Section 757.50(A), p.2857 at https://www.legislature.ohio.gov/legislation/legislation-documents?id=GA131-HB-64

[11] Mark Engel, Bricker & Eckler, Ohio Manufacturers’ Association Tax Counsel, House Bill 59 Testimony before the Ways & Means Committee of the Ohio Senate, May 22, 2013, p.7., cited in Zach Schiller, Tax Breaks Grow in the New State Budget, Policy Matters Ohio, August 8, 2013 at http://www.policymattersohio.org/tax-breaks-aug2013#sthash.EfTqqXN6.dpuf

[12] Ohio Department of Taxation, memo from Doris Mahaffey to Ernest Massie, “Tax expenditure 2.03: Deduction for taxpayers ineligible for employee-sponsored medical plans,” 3/13/2015.

[13] The number reported changed from 128 in 2012-2013 to 129 in 2014-2015 to 128 in 2016-2017.

[14] Not all items in Table 6 are actually newly created. The tax break for venture capital loan losses is not new, but the Department of Taxation did not have a way to estimate the cost, and did not report it before 2016-17.

[15] State legislatures decide whether to adopt changes in federal tax law that affect state tax bases or structure. This is referred to as “coupling,” or integrating federal changes with state definitions. The extent to which state tax law is coupled to the federal varies widely.

[16] Ohio Department of Taxation, memo written by Ted Celmar, “Sales Tax expenditure estimate: Sales of electronically transferred digital products from certain providers,” December 10, 2014.

[17] Ohio Department of Taxation, memo from Doris Mahaffey to Ernest Massie, “Tax expenditure: Credit for venture capital loan loss,” March 13, 2015.

[18] Ohio Legislative Service Commission, House Bill 510 of the 129th General Assembly, final bill analysis at http://www.lsc.ohio.gov/analyses129/12-hb510-129.pdf

[19] Schiller, Zach, “Tax Breaks Grow in New Ohio Budget,” Policy Matters Ohio, Aug. 8, 2013, p. 4, at http://www.policymattersohio.org/tax-breaks-aug2013

[20] Ohio Department of Taxation, Tax expenditure report for 2016-17, Op.Cit.

[21] E-mailed communication from the Ohio Department of Taxation Office of Communications, February 8, 2016.

[22] E-mailed communication from the Ohio Department of Taxation Office of Communications, February 17, 2016.

[23] Ohio Department of Taxation, Tax Expenditure Report for 2016-17, Op.Cit.

[24] Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Bill Analysis of HB 510 of the 129th Ohio General Assembly, Op.Cit.

[25] Id.

[26] E-mailed communication from the Ohio Department of Taxation, Op.Cit. (2/8/2015).

[27] Id.

[28] Id. The Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement governing board provides the following definition of the Agreement: “This Agreement is the result of the cooperative effort of 44 states, the District of Columbia, local governments and the business community to simplify sales and use tax collection and administration by retailers and states. The Agreement minimizes costs and administrative burdens on retailers that collect sales tax, particularly retailers operating in multiple states. It encourages "remote sellers" selling over the Internet and by mail order to collect tax on sales to customers living in the Streamlined states. It levels the playing field so that local "brick-and-mortar" stores and remote sellers operate under the same rules. This Agreement ensures that all retailers can conduct their business in a fair, competitive environment.” http://www.streamlinedsalestax.org/index.php?page=gen_1

[29] E-mailed communication from the Ohio Department of Taxation Office of Communications, February 17, 2016.

[30] See Zach Schiller, “Breaking Bad: Ohio Tax Breaks Escape Scrutiny,” Policy Matters Ohio, June 17, 2013, at http://www.policymattersohio.org/tax-breaks-jun2013

[31] For a more detailed description of these changes, see Zach Schiller, “Tax Breaks Expand in Ohio Budget,” Policy Matters Ohio, Sept. 16, 2015, at http://www.policymattersohio.org/taxbreaks-sept2015

[32] See Ohio Office of Budget and Management, “Tax Reform Scoring Sheet; FY 2016-2017 Operating Budget-All State Funds,” 2015. Ironically, in approving this expanded tax break, legislators increased taxes for 2015 on some business owners. In that year only, the budget bill called for the 3 percent flat rate to apply to 25 percent of the first $250,000 in business income that can’t be deducted. That’s a higher rate than what many business owners had been paying under Ohio’s graduated income tax. The General Assembly inadvertently demonstrated how such a progressive tax is beneficial to lower-income Ohioans with this bill. It moved quickly to approve Senate Bill 208, which reduced taxes on those business owners who would have had to pay more. The Legislative Service Commission estimated the additional cost in FY2016 at $76 million. See Russ Keller, Legislative Service Commission, Fiscal Note & Local Impact Statement, S.B. 208 of the 131st G.A., As Passed by the House, Oct. 27, 2015, at https://www.legislature.ohio.gov/legislation/legislation-documents?id=GA131-SB-208

[33] Legislative Service Commission, Comparison Document, H.B. 64 of the 131st Session of the General Assembly, As Enacted, p. 896, at http://www.lsc.ohio.gov/fiscal/comparedoc131/en/comparedoc-hb64-en.pdf. The LSC assumed in making its estimate that taxpayers do not respond to the policy change by paying themselves less in salary and wages and taking more income in the form of business income. It also noted separately that losses may be somewhat less than $490 million to take into account the income-tax rate cut that was also included in the budget bill. See LSC Greenbooks, H.B. 64 of the 131st General Assembly, Department of Taxation, p. 24, at http://www.lsc.ohio.gov/fiscal/greenbooks131/tax.pdf

[34] State of Ohio, Executive Department, Office of the Governor, Veto Messages, Statement of the Reasons for the Veto of Items in Substitute House Bill 53, April 1, 2015, p. 2, at https://www.legislature.ohio.gov/Assets/AdditionalDocuments/HB-53-veto-message-2.pdf

[35] Ohio Office of Budget and Management, “Tax Reform Scoring Sheet; FY 2016-2017 Operating Budget-All State Funds,” 2015.

[36] E-mailed communication from the Ohio Department of Taxation, Op.Cit. (2/8/2015).

[37] As noted above, the means-testing of this exemption and the $20 credit will reduce the value of these tax expenditures.

[38] The retirement income credit will be means tested now and restricted for use by tax filers with income of less than $100,000; the size of this credit may be expected to decline with new estimates.

[39] Ohio Legislative Service Commission, House Bill 340 final bill analysis at https://www.legislature.ohio.gov/download?key=4157&format=pdf

[40] Policy Matters Ohio’s testimony on the bill before the Senate Ways & Means Committee includes more specific ways that disclosure could be strengthened. See http://www.policymattersohio.org/hb9testimony-oct2015.

Tags

2016Revenue & BudgetTax ExpendituresTax PolicyWendy PattonPhoto Gallery

1 of 22