Overhaul: A plan to rebalance Ohio's income tax

June 25, 2018

Overhaul: A plan to rebalance Ohio's income tax

June 25, 2018

By Wendy Patton and Zach Schiller

INTRODUCTION

Ohio needs a new tax policy, one that raises the revenue needed to provide excellent schools, strong public transit and treatment for Ohioans caught in the state’s drug epidemic. Dramatic tax cuts since 2005 have weakened the state’s ability to meet these and other needs and created an upside-down system that causes those near the bottom of the income scale to pay nearly twice the share of their income in state and local taxes as the top 1 percent, who earn more than $1 million a year on average. Policy Matters Ohio outlines here a set of changes to the state income tax—the only major tax based on the ability to pay—that will bolster our ability to make key investments in education, human services and local governments. It will begin to reverse the slant of our tax system against low- and middle-income Ohioans—yet because state and the recent federal tax cuts have been so enormous, few of even the richest residents will be paying more overall when our proposed increases are added to recent cuts.

The Ohio General Assembly has approved major state tax cuts since 2005. State policymakers abolished the corporate income tax and the business tangible personal property tax and replaced them with a tax on gross receipts that brings in half as much in total revenue. They ended the estate tax, which had been paid only on estates worth more than $338,333. But the biggest changes were to the personal income tax. Policymakers cut income-tax rates by a third since 2005.[1] In 2013, they created a state level deduction for income from limited liability companies and other businesses known as passthrough entities and then expanded it to include a tax cut for such income. It is now costing Ohio more than $1 billion a year, based on current tax rates.[2] Since the 2005 tax cuts, Ohio job growth has lagged the national average and the median wage is lower than the national average.[3]

Ohio has cut taxes, while underinvesting in education. We are falling behind many states in the share of low-income children who go to preschool;[4] our schools lost 3,200 social workers, guidance counselors and music, art and gym teachers between 2005 and 2014;[5] our public higher education system is now one of the most expensive in the nation and need-based financial aid has not kept up.[6] Yet, it’s clear that high-wage states are states with a well-educated workforce.[7]

Approval of the new federal tax bill underlines the need for a progressive tax policy in Ohio, one that raises much-needed revenue from those who can most afford it. There are pressing needs in addition to education that the state fails to address adequately because of lack of revenue. One is funds to fight the drug epidemic. Ohio had 5,232 drug overdose deaths in the 12-month period ending July 2017, the third highest in the nation; the number of deaths grew by 39 percent over this time period compared to the same period a year earlier.[8] Ohio ranks last in state funding of children’s services, even after the boost in the current state budget.[9] State funding for public transit remains a third of what the state Department of Transportation recommended in 2015.[10] Local governments have lost $1 billion a year in state aid, making it harder to fight the drug epidemic, repair crumbling bridges and ensure basic services like public safety and infrastructure repair.[11]

In short, Ohio needs to invest. To do so, we should reverse income-tax cuts that send money to Ohio’s most affluent residents and boost the rates that they pay. At the same time, to start cleaning up our upside-down state and local tax system,[12] we need to strengthen our state earned income tax credit (EITC) to address the fact that low-income people now pay a much bigger share of their income in tax than the wealthiest. Policy Matters proposes the following changes to the state income tax:

- Restore the 7.5 percent income-tax rate on income over $218,250 approved in 1992 under Gov. George Voinovich;[13]

- Add a new 8.5 percent rate on income over $500,000;

- Repeal the business income deduction enacted in 2013, which is draining more than $1 billion a year from state revenues with little discernible impact on jobs or small-business growth, and.

- Make our state earned income tax credit refundable, removing a cap that reduces the amount many Ohioans may receive, and raising it to 20 percent of the federal amount.

This would generate almost $2.6 billion a year, including the cost of expanding the EITC, according to analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), which has a model of the tax system. It would still leave Ohio’s richest taxpayers with overall annual state tax cuts averaging more than $2,000 a year—and they’ll be receiving additional giant tax cuts because of the federal tax bill approved last December. Many low- and moderate-income Ohioans, some 17 percent of tax filers in all, would see a tax cut if these state tax changes were enacted. Another 71 percent would see no change in what they pay.

Ohio’s tax cuts have benefited the affluent

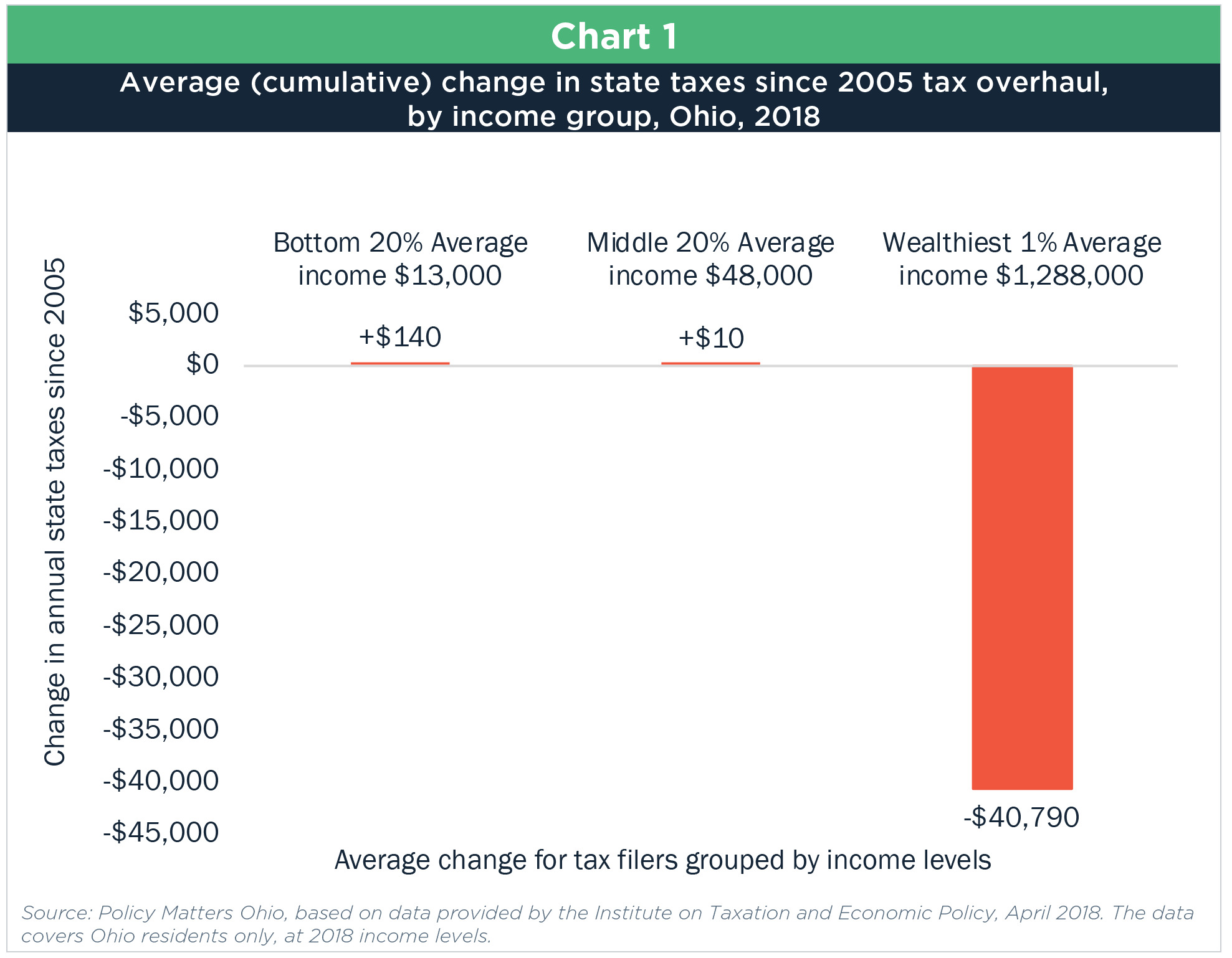

Changes in Ohio’s taxes since 2005 have disproportionately benefited the highest income earners. ITEP analyzed the major changes in Ohio’s tax system since 2005 for Policy Matters, including changes to the personal income tax, sales tax, cigarette tax, business taxes, and other changes. It found that these major changes have provided the top 1 percent of earners, who make at least $480,000 a year, with an average cut of $40,790 a year. That compares to an average increase of $10 for the 20 percent of filers in the middle of the income ladder, who make between $39,000 and $59,000, and an average increase of $140 for those with the lowest 20 percent of incomes (Chart 1), who make less than $22,000 a year.[14]

The state tax cuts are more generous to the wealthy by design. They are skewed toward Ohio’s high-income tax filers when measured as a portion of their own incomes. While people in the bottom 20 percent of earners averaged a tax increase of 1.1 percent of total income, and there was no change on average for the 20 percent for people of middle income, the cuts totaled 3.2 percent of earnings, on average, for the richest 1 percent of Ohioans (See Appendix Table 1 for more details).

A large component of state tax cuts, as mentioned, came from the rate reductions and the big new exemption for business income under the personal income tax. A separate ITEP analysis found that the top 1 percent got more than 30 percent of the benefits of these cuts and other changes in the income tax.[15] The bottom 60 percent in terms of income got just 12 percent of the income-tax cuts enacted over this 13-year span (Chart 2).

Ohio tax cuts on business and business income

Under both Republican and Democratic administrations, Ohio has cut more than $6 billion a year in taxes since 2005.[16] Thirteen years later, we have less revenue to fund programs that make communities strong and we trail the nation in job growth. Ohio job growth has lagged behind the nation’s, growing just 3 percent since June 2005 when a big tax overhaul was enacted, while nationally, the employment growth has been more than 10 percent.[17] Ohio’s growth in wages, real output, employment and personal income is forecast to lag the nation in the 2018-2019 state budget period, as it did in the prior budget period, and the one before that.[18]

Ohio reduced taxes on business income from passthrough entities in 2013 and expanded this tax break since then (they are known as “passthrough entities” because their profits are taxed under the individual income tax as they pass through to their owners). This is also known as the LLC loophole because it enriches owners of limited liability companies or LLCs.

Today, a taxpayer does not have to pay Ohio income tax on the first $250,000[19] in passthrough income, and only pays a 3 percent tax rate on such income over and above that—a rate lower than the 4.997 percent top income tax rate in Ohio. As a result, the LLC loophole drains more than $1 billion annually from state revenues, based on current rates. The cost is even larger if you factor in the reduction in tax rates since 2005. In 2015, just 5 percent of the wealthiest tax filers, those claiming passthrough income of more than $250,000 a year, received a third of the total value of this tax break.[20]

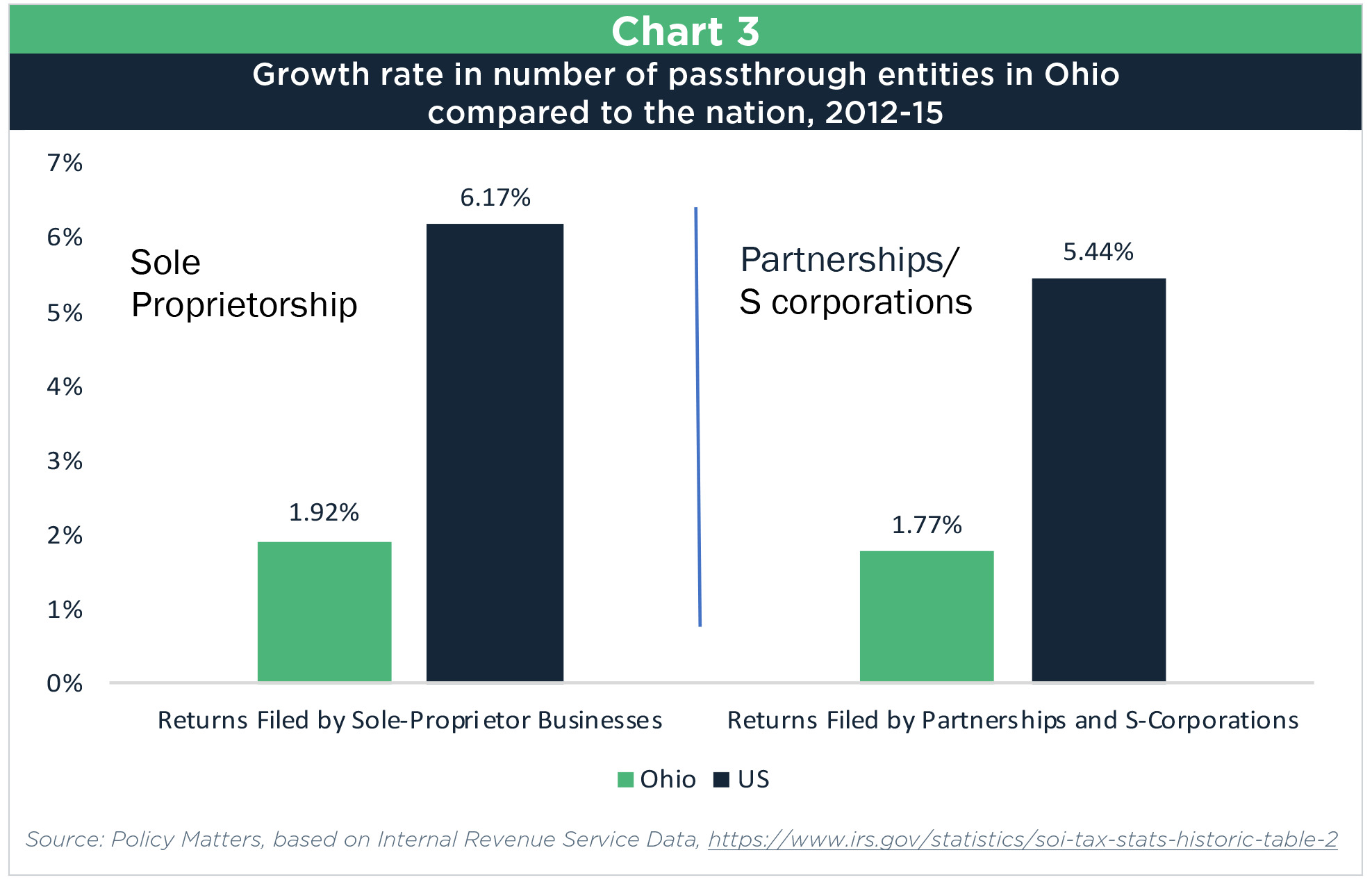

This tax break was touted as a tool to spur creation of new firms and to create jobs, but it has not done so. The vast majority of those receiving the break save less than $1,000 a year, nowhere near enough to hire a new employee. Data from the Internal Revenue Service shows (Chart 3) that the growth rate of new businesses, based on number of returns from sole proprietorships, partnerships and S corporations, was slower in Ohio than the nation as a whole from 2012, just prior to the enactment of the tax break, to 2015.

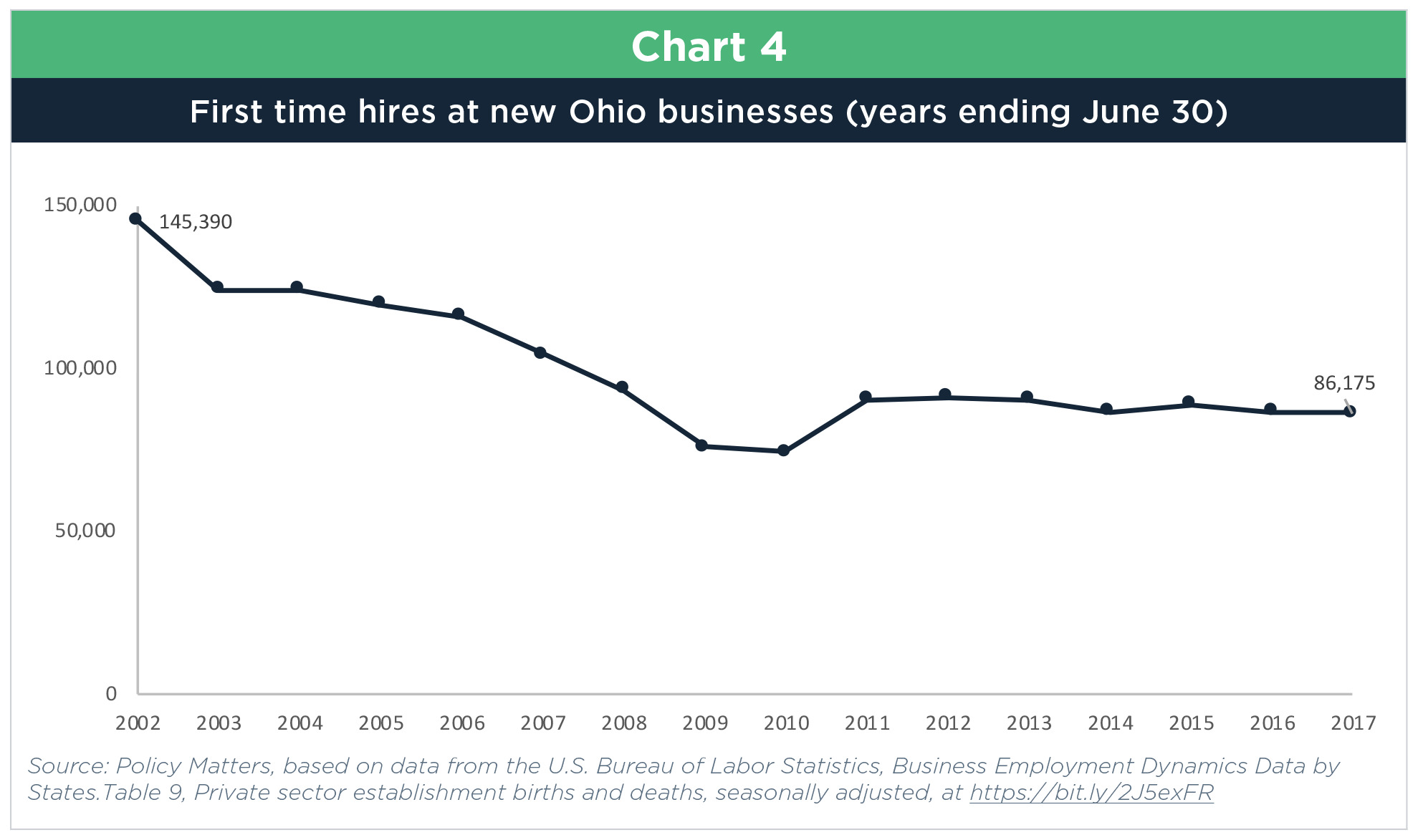

Nor has employment at new Ohio businesses seen an uptick. Chart 4 shows new hires at Ohio businesses hiring for the first time. The trend line is flat since the tax break was enacted in June 2013.

A plan to restore Ohio

Recently, deep federal and state tax cuts have given additional enormous benefits to the affluent and to corporations. On the state level, these have been paid for by cuts to investments that help families, maintain communities and build opportunity for the future; this could well be the case with the federal cuts as well. The changes in federal tax and budget policy will be particularly harmful to Ohio, after years of similar economic approaches have left the state with sluggish economic growth, unmet needs and an inequitable tax structure.

Ohio’s tax system is weighted against low- and middle-income Ohioans, who pay a higher share of their income in state and local taxes than wealthy Ohioans. Taking tax changes through early 2016 into account, the bottom 20 percent of nonelderly residents paid 11.9 percent of their income in state and local taxes, nearly twice as much as the top 1 percent of earners, who paid 6.1 percent.[21] This is because sales, excise and property taxes fall more heavily on those at the bottom of the income scale. Ohio’s income tax is the only major tax that is based on ability to pay, and it has been cut dramatically. The situation demands a new approach that raises revenues for essential services from those who can afford to pay and begins to rebalance our tax system so it is not as weighted against low-income Ohioans.

Ohio should reclaim its place as a high-wage state through long-term investments in the education and welfare of residents and by restoring state support to public transit, libraries, and important services provided by local governments. To raise the necessary revenues and provide more balance, as detailed on page 2, Policy Matters proposes restoring the previous 7.5 percent top rate, adding a new 8.5 percent rate on earnings over $500,000, repealing the LLC loophole and improving Ohio’s EITC. This would generate almost $2.6 billion a year, while still leaving Ohio’s richest taxpayers with overall annual tax cuts worth many thousands of dollars a year as a result of earlier state tax cuts and the recent federal tax cuts.

Restoring the state revenue system so it is stronger and more equitable

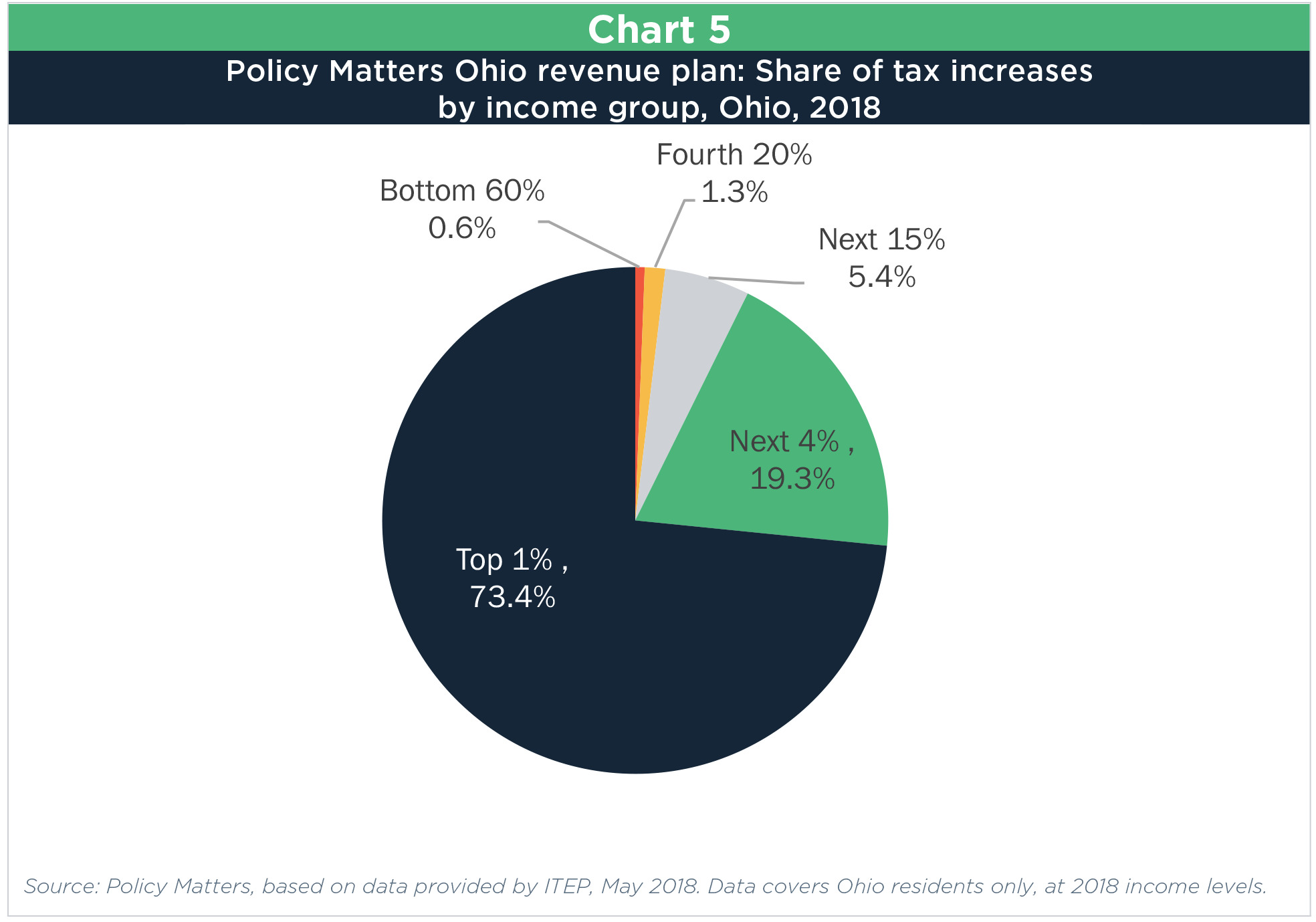

Chart 5 shows the distributional impact of the personal income tax changes recommended above. The top 1 percent, those earning more than $480,000 and with an average income of nearly $1.3 million a year, would pay 73 percent of the increase. The next 4 percent, earning more than $194,000, pay 19 percent of the tax increase. Very small numbers of those in the bottom 60 percent of Ohio earners, making less than $59,000 a year, would pay more under the plan; in total, the amount paid by these tax filers adds up to less than 1 percent of the total. What Ohio residents gain from this is better funding for schools, so there can be more guidance counselors and art, music and gym teachers, and less pay to play; local governments with better ability to keep streets safe and well-repaired; clean and safe parks and beaches, longer library hours, and overall restoration of many services that have been slashed due to tax cuts for the wealthiest.

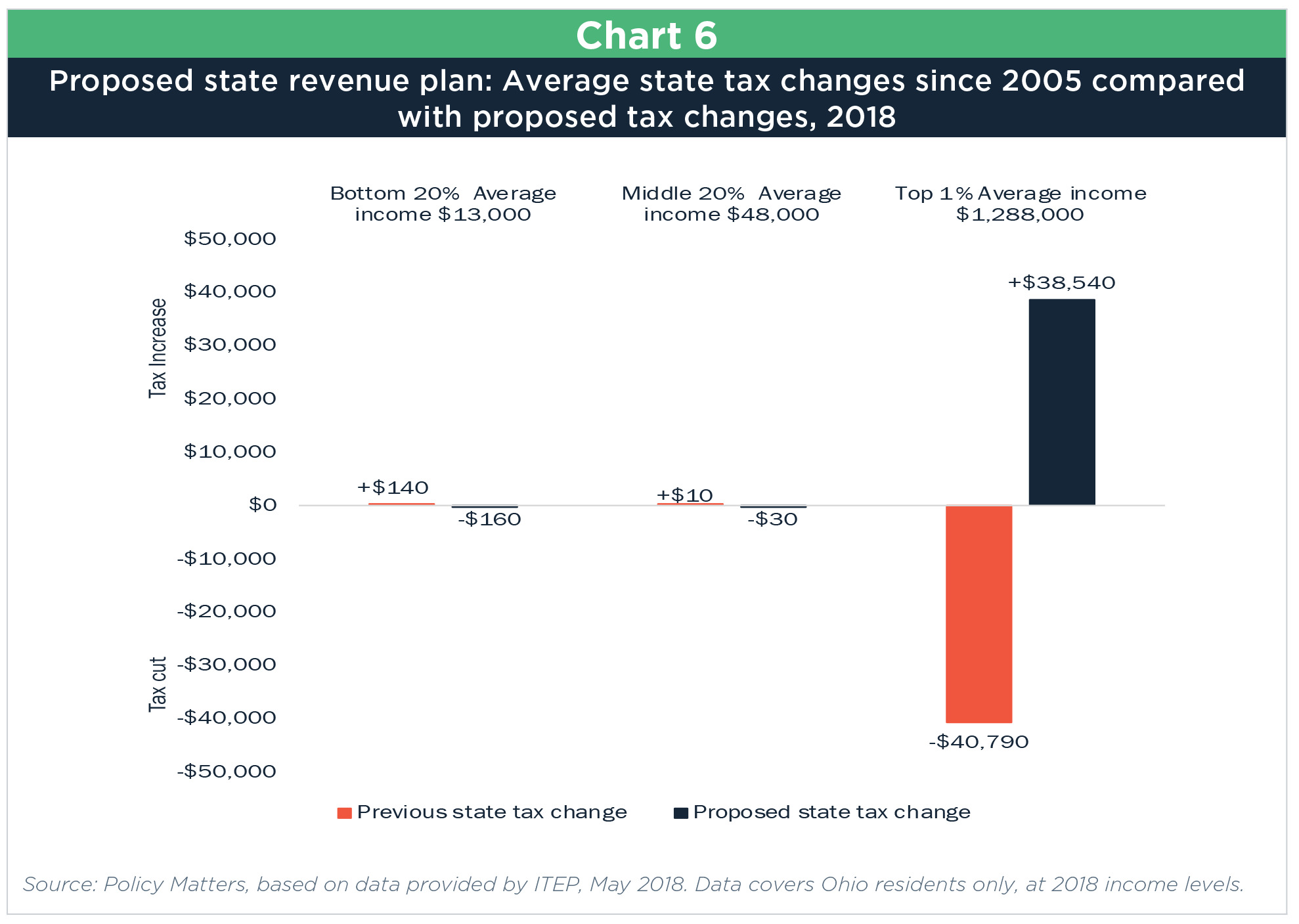

State cuts since 2005 more than offset the average increase for any Ohio income group from this tax plan, which would restore revenues badly needed to properly invest in schools, communities, infrastructure and human services. In fact, the state income-tax cuts alone have provided the top 1 percent of earners with an average cut of $37,830 a year. Altogether, this group has seen average annual state tax cuts of $40,790. The plan presented here would still leave the most affluent Ohioans with a reduction in average state and local taxes of more than $2,000 a year (Chart 6; see Appendix Table 3 for more information). The state revenue plan proposed here would more than offset the increase in taxes paid by the lowest income Ohioans as a result of state tax changes since 2005 and also leave tax filers in the middle-income group with a very small tax cut on average.

Under the proposed state revenue plan, the top 1 percent of earners would, on average, pay an additional 3 percent of income in state taxes, less than the previous state tax cuts. Overall, 88 percent of Ohioans would not see a tax increase under this plan.

Most people, wealthy or not, want strong and vibrant communities. Increasing taxes on top earners does not cause a stampede of wealthy residents across state lines in search of lower rates. The most striking finding of a recent study that reviewed every federal tax return with more than $1 million in reported income between 1999 and 2011 “is how little elites seem willing to move to exploit tax advantages across state lines in the United States.”[22] Budget experts from California and New Jersey, two states with relatively high taxes on top earners, concluded in a recent article: “The new revenue has helped improve our states’ economies by supporting vital investments in education and infrastructure. And rather than suffer from millionaire migration, our states have grown million-dollar earners at a healthy rate—in fact at greater rates than many low- or no-tax states.”[23]

Why restore tax revenues and balance the state and local tax structure?

In the early and mid-20thCentury, people from across the country and around the world flocked to Ohio for jobs. During that time, state leaders made big, visionary investments in things like public parks, public universities and roads and highways. Cutting state and local taxes is not an effective method for creating jobs, nor is raising them a recipe for reducing them.[24] “Ohio raised taxes in the recessions of the 1980s and 1990s to fund vital public services, and job growth was strong during the economic recoveries that followed,” noted Jon Honeck in a 2009 report for the Center for Community Solutions. “In the current decade, the state saw moderate job growth under a temporary sales tax and then lost jobs starting in 2006 after taxes were cut.”[25] The experience since 2009 has further underlined the correctness of his statement.

By 2017, the 12thyear of almost annual income tax cuts in Ohio, total job growth was 32,200 for the entire year, compared to over 100,000 a year after earlier tax increases in the 1980s and 1990s.[26] Growth has picked up in 2018, but still trails the nation’s gain over the past 12 months.[27] Since 2005, the number of Ohio jobs has grown by 3 percent compared to the national average of more than 10 percent.

Deep tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations have not made the Ohio economy more competitive. Job and wage growth remain sluggish compared to the nation. Ohio needs, instead, to invest to boost productivity—in infrastructure, schools, colleges, universities and basic social services.

High-wage states generally have a well-educated workforce. There is a clear, strong correlation between educational attainment and median wages in the state.[28] Investing in education is also good for state budgets in the long run, since workers with higher incomes pay more taxes over their lifetimes. But it takes real investment: from quality early education through well-funded public schools to strong, affordable colleges and universities. Ohio has fallen behind badly in many of these areas, particularly for low- and middle-income families:

- In 2000-2001, Ohio ranked 19thamong states in number of 4-year-olds enrolled in state pre-K, special education or Head Start but slipped to 32ndby 2017. The share of Ohio children enrolled did not change much over time—25 percent in 2000-2001 and 26 percent in 2016-2017—but other states increased enrollment: nationally, the share rose from 31 percent in 2001 to 44 percent by 2016-17.[29] Ohio fell behind.

- A billion dollars a year are siphoned from Ohio’s public schools to mostly poorly performing charter schools. Between the deep cuts of the first Kasich Administration budget and loss of funding to charter schools, many districts have shed social workers, guidance counselors, and art, music and gym teachers.[30]

- Ohio’s per-student spending on higher education fell by 15.2 percent adjusted for inflation between 2007 and 2017.[31] In 2016, only five states required higher payments as a share of family income than Ohio,[32] yet Ohio lawmakers have cut financial aid since 2005.[33] Ohio’s contribution to need-based financial aid per-student at public institutions is much lower than the national average.[34]

A stronger Earned Income Tax Credit

Ohio’s state and local tax system also needs an overhaul because it is slanted against low-income residents. Even before the General Assembly slashed the income tax and increased sales and cigarette taxes, poor Ohioans paid somewhat more of their income in state and local taxes than their more affluent neighbors.[35] Now, that disparity is far greater, as the fifth of tax filers making less than $22,000 a year on average pays nearly twice the share that the top 1 percent pays.

The Earned Income Tax Credit is one key way the state can address this and rebalance our tax code. The EITC is a credit paid through the income tax system that goes to workers who meet income guidelines. But Ohio’s existing credit is too weak to help the workers who need it most. Modeling from ITEP shows that Ohio’s EITC reaches only about 3 percent of the state’s neediest working families and 9 percent of middle-income workers. A 20 percent, refundable, non-capped EITC would extend the credit’s reach to more than a third of the state’s poorest (36 percent) and increase the amount available to all eligible claimants. These changes would mean fewer working Ohioans would be taxed into poverty. This would require an estimated $425 million in state income tax credits, a reasonable cost to support work and local spending and to bring more balance to Ohio’s tax code.[36]

The EITC is a proven tool to build an inclusive economy. The federal credit helps working families make ends meet when many jobs fail to provide enough income for basic needs.[37] It supports spending on things like child care and transportation that allow families to keep working. And the federal EITC lifted 5.8 million people out of poverty in 2016.[38] Moreover, it has a lasting effect. Children in households that receive the federal EITC are born healthier, do better in school, have higher college attendance rates and even earn more as adults, compared with their counterparts whose families don’t get the credit.[39]

But the current Ohio EITC, first enacted in 2013, has three defects.[40]

First, it is not refundable, meaning that many of the poorest Ohioans can’t get the full value of the credit. The federal EITC and 24 of the credits in 29 other states (including Washington, D.C.) provide tax refunds if a taxpayer’s credit works out to more than their income-tax liability, but Ohio’s does not.[41] Though low-wage Ohioans may not pay a lot in state income tax, they pay more in other taxes as a share of income than much more affluent residents. Making the credit refundable is crucial to improving the reach of the EITC and making it meaningful for the lowest-income Ohio workers. ITEP’s analysis shows that just a tiny fraction of the poorest Ohioans benefit from the EITC as currently structured.

Second, Ohio has a unique cap. A taxpayer with Ohio Taxable Income greater than $20,000 can only claim an EITC that is half the amount of state income tax owed, after applying certain exemptions. Unlike the federal credit, which has a long phase-out so workers only gradually lose their EITC as they earn more, this means that workers who are earning their way into the middle class receive less EITC support than they should.

Finally, Ohio’s 10 percent EITC is too small. It is below the value of many other state refundable EITCs, which average about 17 percent of the federal credit.[42] The Ohio tax code includes refundable income-tax credits for motion picture producers and historic building rehabilitators, as well as $84 million last fiscal year in refundable business tax credits.[43] It has no refundable credits for working class people.

A refundable, non-capped Ohio EITC would add balance to the tax code, prevent some workers from being taxed into poverty, provide an income boost, and better leverage the benefits provided by the federal EITC.

Changes to federal tax law

The new federal tax law provides additional reason to update Ohio’s tax system. It reduces federal revenues over the next decade by approximately $1.5 trillion, largely by slashing tax rates for corporations and the wealthiest, owners of partnerships and other passthrough firms, and people receiving inheritance from very large estates.[44] The law provides much smaller, temporary tax reductions to many ordinary wage- and salary-earners. By 2027, most Ohioans will see no residual benefit or will be paying a little more than under prior law. Yet the top 1 percent will continue to enjoy tax cuts averaging thousands of dollars a year.[45]

The federal tax law cuts personal income tax rates and makes a host of additional changes:

- The standard deduction is doubled and personal exemptions are eliminated. For those who do not take the standard deduction and instead separately itemize deductions from federal taxable income, the deduction for state and local taxes is capped at $10,000 and the interest deduction for mortgages is capped at $750,000 (the cap had been set at mortgages of $1 million or less.) While these caps affect many Ohioans, they have less impact here than in other states with higher incomes, tax rates and mortgage costs.

- The child tax credit is doubled to $2,000 and eligibility rises from $110,000 to $400,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly. The benefit remains too small to significantly help middle- or low-income families with small children struggling with the high cost of child care, yet is unneeded by top earners.[46]

- Up to 20 percent of business income taxed under the personal income tax can be deducted, with certain limitations. This benefits owners of partnerships, S Corporations and other businesses known as “passthrough entities,” the same basic group that gets a windfall from Ohio’s LLC loophole, although the federal law includes some additional restrictions.

- The corporate tax rate is cut from 35 percent to 21 percent starting in 2018 and even lower rates are set on the U.S. taxes that multinationals would pay on past foreign profits.

- The exemption for taxation of assets left to heirs is doubled from $11 million for a married couple to $22 million. Under prior law only 0.2 percent of estates were taxed, so only extremely rich estates will pay any estate tax whatsoever. Under prior law in 2018, just 140 estates, 0.1 percent of all Ohio estates, would have paid the estate tax; that likely has now been further slashed.[47]

How the federal tax bill affects Ohio’s revenues and budget

The federal tax law’s effect on Ohio’s tax system is much less significant than in some other states, for several reasons. First, Ohio repealed its corporate income tax and estate tax, limiting the effects of change in those federal taxes. Substantial federal changes in business taxes only ripple through Ohio’s tax system as they affect owners of passthrough entities. Since Ohio already has a huge tax break of its own on such income, much of that is already not taxed in Ohio, further limiting the effect.Ohio’s income tax, like those in most states, begins with adjusted gross income as defined on line 37 on the federal income tax form. Changes in federal deductions like the one for mortgage interest, reduced in the new U.S. law, will not affect what Ohio collects because they are taken after that adjusted gross income line. Similarly, the enormous new federal tax break for owners of passthrough businesses does not impact the Ohio tax base because of how the federal law was written. Ohio also does not automatically conform to federal changes. Ohio bases its income tax on the federal tax at a fixed earlier point in time, so lawmakers here can choose how to conform with federal changes. After an earlier change, for instance, Ohio chose to decouple from federal law and add back much of the depreciation expense that federal law would allow to be written off immediately. As of now, the only major changes Ohio has made relative to the new federal tax law, included in Senate Bill 22 of the 132nd General Assembly enacted in March, include clarifying that the state personal exemption remains available for dependents, and allowing people to use tax-advantaged college savings accounts for private K-12 school tuition.(1)

Some federal changes will directly affect how much Ohioans pay in state income tax. These include reduced deductions for moving expenses, elimination of alimony as either income or deductions, and changes in business taxes, covering deductions for interest and net operating losses as well as handling of depreciation. The volume and complexity of the federal changes make the effect on Ohio taxes impossible to predict precisely. But the taxation department estimated only minor revenue impact.(2)

One provision that will affect the state budget is the change in rules around tax-advantaged college savings accounts, cited above. Ohio’s legislature has accepted the new federal rules around what money in such “529” college savings accounts can be used for, now allowing deductions for K-12 private school tuition. The tax department anticipates this will nearly double the current tax break to more than $40 million annually. This benefits upper income families and will pump millions of dollars of state resources into private schools that are better spent supporting public education.(3)

(1) Jackson, Victoria, Testimony on SB 22 before the House Ways and Means Committee, Feb. 27, 2018 at https://bit.ly/2IYKWSP; the state tax department did not estimate the fiscal effect of eliminating the income-tax exemption for dependents in the absence of Ohio legislation, but it could have been significant.

(2) Keller, Russ, Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Fiscal Note & Local Impact Statement, S.B. 22 of the 132nd G.A., As passed by the House, Feb. 28, 2018, at https://bit.ly/2snyYGU and Ohio Department of Taxation, Notable Estimates, S.B. 22, at https://bit.ly/1F6qVx6, included with testimony from Tax Commissioner Joe Testa, Feb. 20, 2018

(3) Ibid. and see Victoria Jackson, Op. Cit.

The provisions that affect families and individuals mostly expire after 2025, except for changes in the way inflation is measured that will gradually push households into higher tax brackets and reduce the value of the EITC, hurting some working families, and elimination of penalties for not having health insurance (the “individual mandate”) that may cause more to become uninsured and raise premiums.[48] The estate tax cut and the provisions for passthrough business owners also expire after 2025. The 40 percent cut in corporate tax rates is permanent.

Distributional impact of the federal tax law

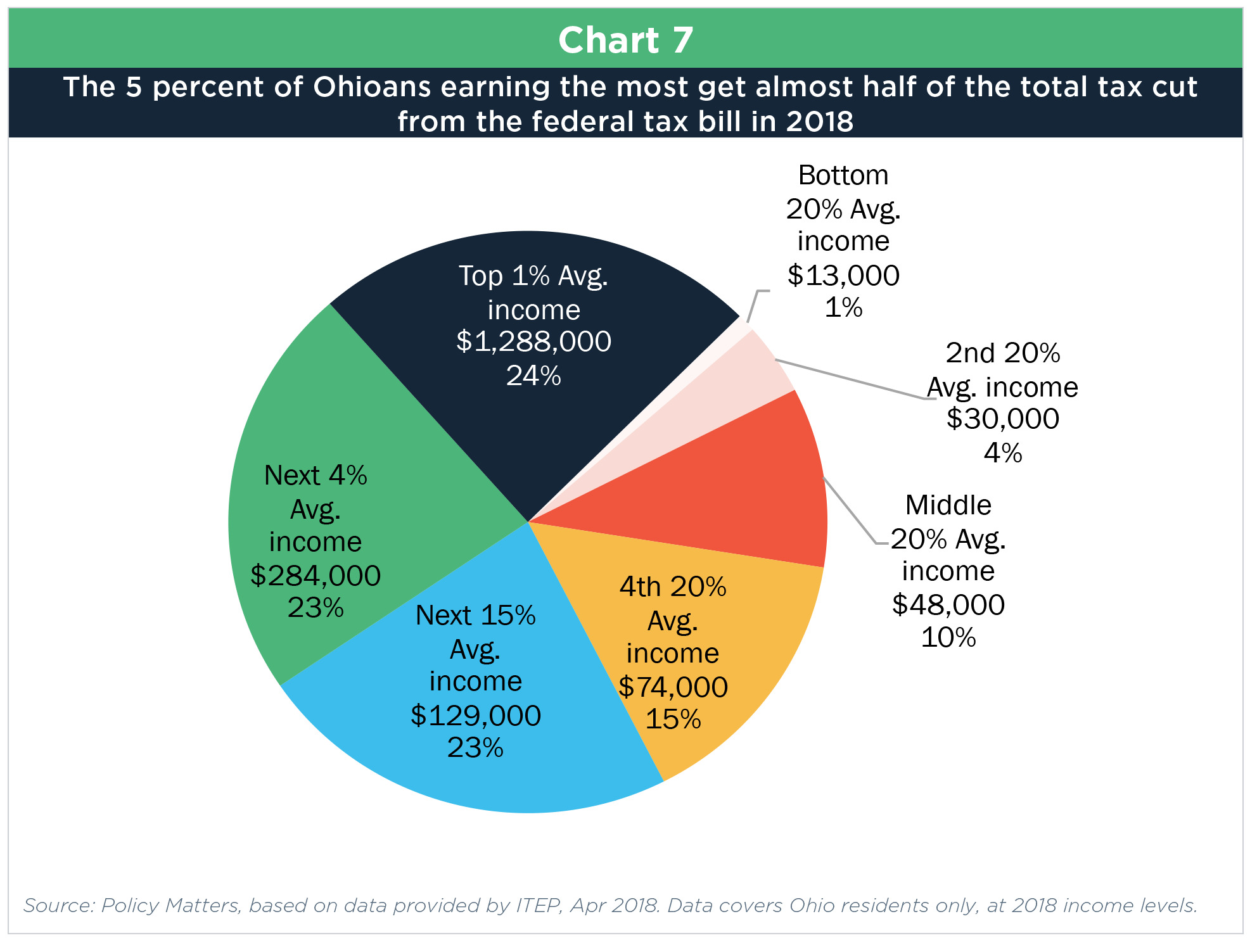

The highest income groups will receive the lion’s share of the federal tax cut in Ohio. In 2018, the top 1 percent, earning more than $480,000 and with an average income of nearly $1.3 million, will get almost a quarter of the total tax cut, $2.3 billion in total tax cuts. The next 4 percent, who make between $194,000 and $480,000, will get $2.2 billion. Chart 7 shows how the 5 percent of Ohioans with the highest income, combined, get nearly half of the value of the $9.7 billion value of the entire tax cut this year. The bottom 60 percent of taxpayers, earning no more than $59,000, will get just 15 percent of the tax cut coming to Ohio in 2018.[49]

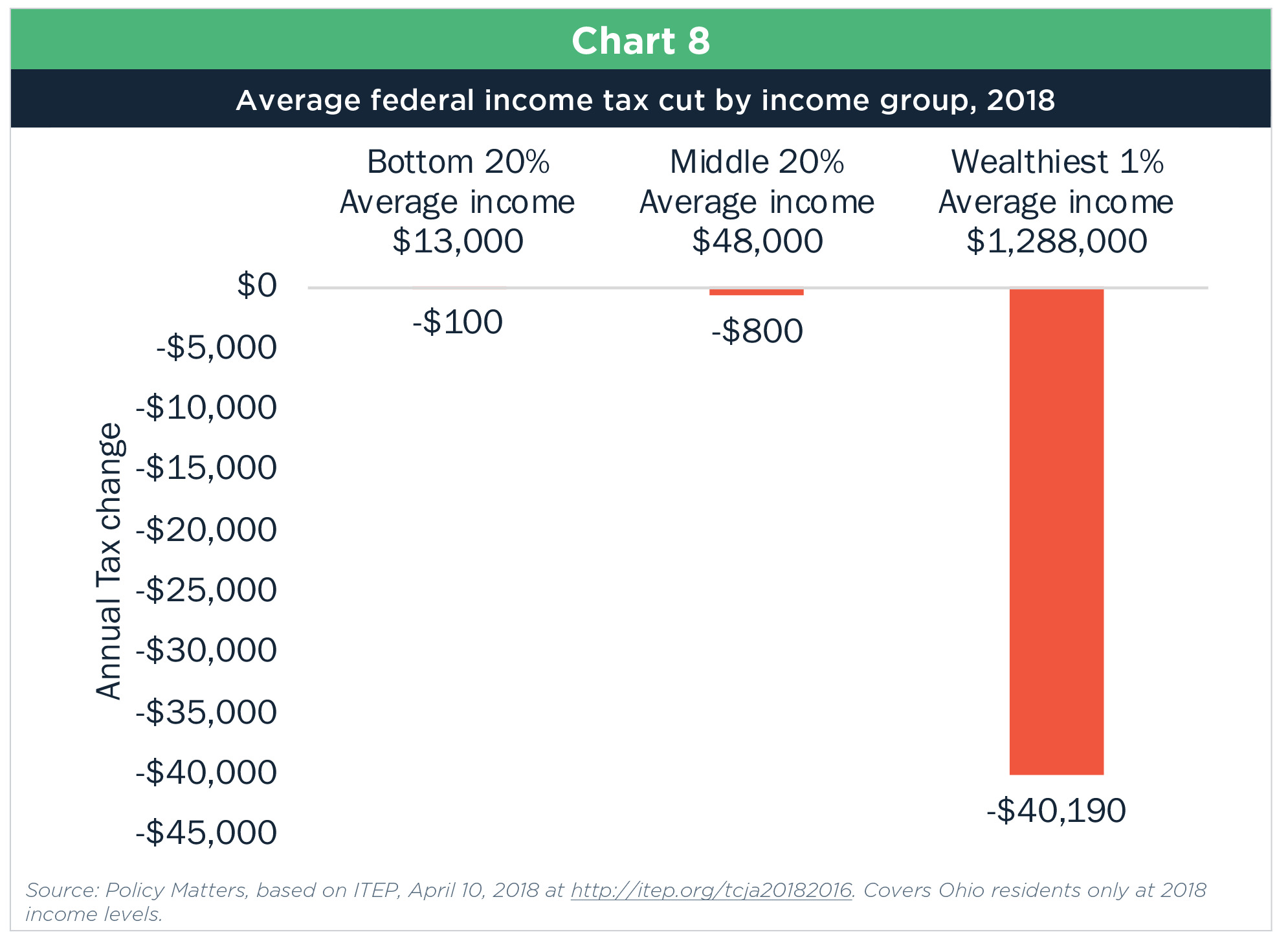

The new federal tax plan gives an average tax cut of $40,190 in 2018 for the highest-income 1 percent of Ohio tax filers, compared to an average of $800 for the 20 percent of filers in the middle, who make between $39,000 and $59,000 a year. For those in the lowest 20 percent, earning less than $22,000 a year, the average will be $100 this year (Chart 8; see Appendix Table 2 for details). The amounts of the federal tax cut diminish over the years but still leave the top 1 percent with thousands of dollars in annual tax cuts.

Wealthy taxpayers do not get the biggest cut simply because they pay more taxes: The new federal tax rules are more generous to high-income taxpayers than to others when measured as a portion of their incomes. The wealthiest tax filers see a federal tax cut averaging 3.1 percent of total earnings in 2018; the middle group gets a cut of 1.7 percent of total earnings, and the bottom group gets a cut of only 0.8 percent of their very low total income. Cutting taxes for the wealthiest by design is similar to what has happened at the state level as well.

Combining the Policy Matters tax plan with U.S. and state tax changes

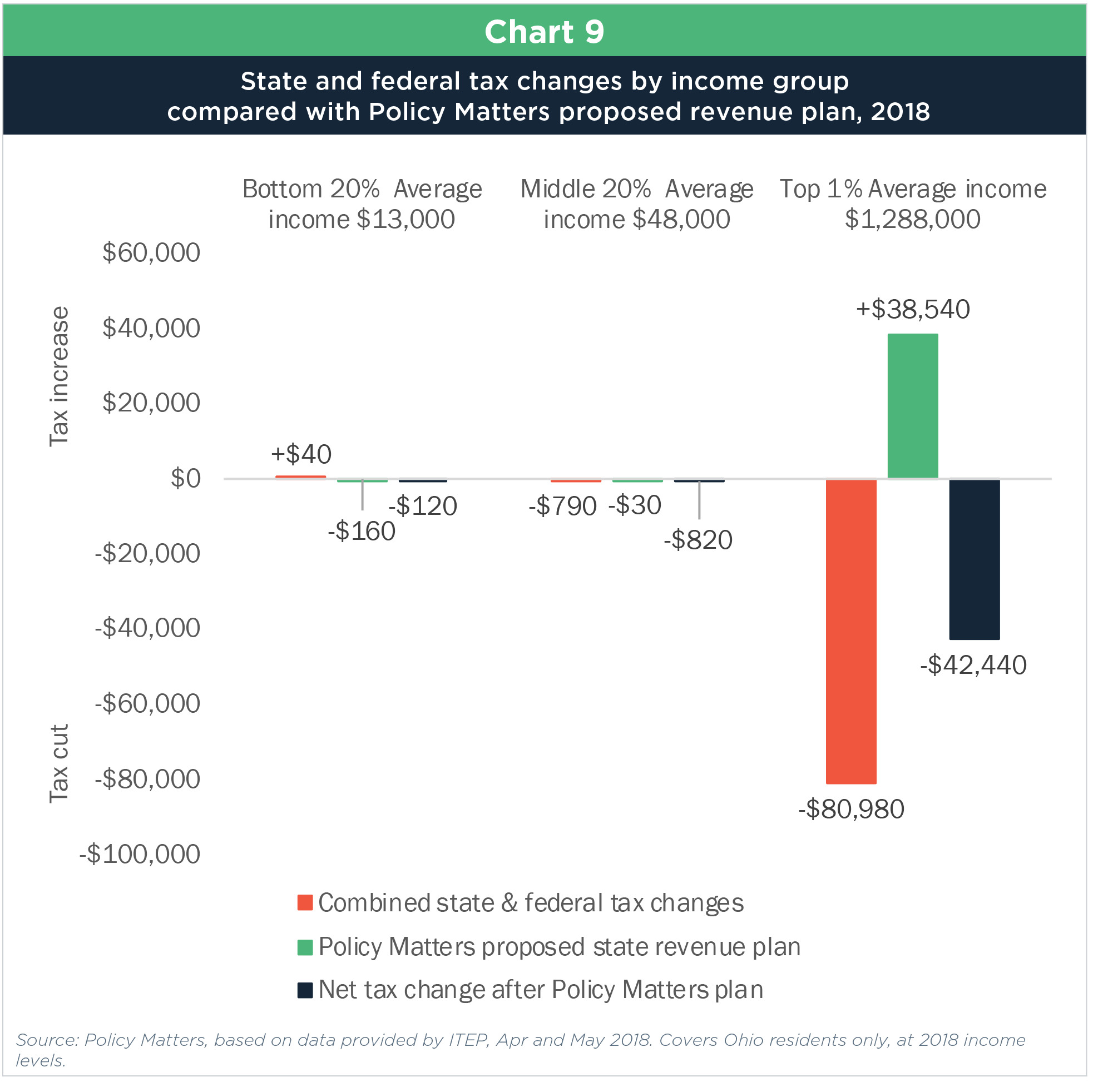

If you add the effects of the federal tax law to the state tax changes we’ve seen since 2005, it’s clear the most affluent Ohioans would still see major tax cuts even after taking into account the Policy Matters Ohio tax proposal. Chart 9 shows the combined effects of the state and federal tax changes and the tax proposal. In 2018, the wealthiest taxpayers would see an average gain of $42,440. Lower- and middle-income tax filers, who average small to moderate tax cuts under the Policy Matters proposal, also would see average reductions from the combined effects of these tax changes, though small ones by comparison.

Although the direct effect of the federal tax plan on Ohio’s state revenue collections is not large (see box, above), there could well be an indirect effect as President Trump and Republican leaders in Congress press to slash program funding as outlined in budget resolutions and the President’s budgets.

The federal tax plan increases the federal debt by an estimated $1.5 trillion over 10 years. This will build political pressure to cut federal programs that Ohio families rely on in the low-wage economy. This is not speculation. The budget resolution through which the tax plan was created included proposals for deep cuts to Medicaid, Medicare and other programs. The Trump budget proposal for 2018 would have cut Medicaid and subsidies for private coverage in the marketplace by $763 billion over the next decade, with cuts reaching $172 billion annually by 2028.[50] Congress passed a spending bill for the rest of 2018 that does not do the damage feared last year, but a budget fight for 2019 is looming in September, and Trump’s 2019 budget proposal is as harsh as his 2018 one. Moreover, deep cuts in programs outside of the annual budget process, like for federal food aid and other safety net programs, are moving forward[51] under the leadership of House Speaker Paul Ryan, who has long advocated slashing programs that help struggling families.[52] The House version of the federal farm bill would cut $19 billion over 10 years from food assistance, increasing hunger for more than 1 million low-income households—particularly families with children.[53] The Senate version avoids such harmful cuts,[54] but when struggles between the House and the Senate over human service spending conclude, the Trump Administration maneuvers through the courts and agencies to try and get its way.[55] In this case, it’s to cut spending that helps struggling families to pay for the giant federal tax bill.

Cuts like this will hurt many Ohioans. Six of Ohio’s 10 most common jobs leave a family of three eligible for and needing help to put dinner on the table even with full-time work.[56] The government helps make up the difference. Medicaid provides health care for 3 million people, a quarter of the Ohio population, paid for in large part by about $20 billion federal dollars. The federal food aid program, SNAP,[57] serves about 1.4 million Ohioans, mostly families with children, elderly and disabled people. Nearly 84,000 Ohio households with children make so little money that they are eligible for federal help to pay the rent—yet only one in four eligible families gets help with housing in America.[58] These programs are targeted for deep cuts. As federal cuts occur, state and local governments will be faced with hard choices about where to backfill and what to cut.

Summary and conclusion

Ohio’s economy needs long-term investments in the education and welfare of residents and restored state support to local governments, public transit and libraries. The state can pay for this by restoring state income taxes on the richest households. This would reverse only some of the state income-tax cuts the most affluent 1 percent of Ohioans have received; they still will be paying less in overall state and local taxes and getting large federal tax cuts. Others would pay less in Ohio taxes than they were before the tax cuts began in 2005. The tax changes would have no effect on what the overwhelming majority of Ohioans pay in income tax, while a stronger state Earned Income Tax Credit would mean that many low- and moderate-income residents would pay less than they do now. The restorative revenue plan proposed here will make Ohio’s state and local tax structure more fair than it is today. It will also allow state and local governments to prepare for possible federal cuts in critical services in many areas. Rebalancing the tax code is a key to a more prosperous, equitable Ohio.

APPENDIX

Appendix Item 4

The full ITEP analysis included all of the following items listed below. Only the first seven items were included in a separate analysis of changes in the personal income tax.

- The 21 percent cut in income-tax rates enacted in 2005, full 10 percent reduction in rates approved in 2013 and the 6.3 reduction approved in 2015.

- The reduction in the number of brackets from 9 to 7, bracket indexing of the income tax, and the creation of a new $10,500 threshold for the tax. This superseded the credit approved in 2005 that wiped out income-tax liability for those whose Ohio adjusted gross income (minus exemptions) does not exceed $10,000.

- The 10 percent capped nonrefundable state Earned Income Tax Credit.

- The creation and later expansion of a new income-tax deduction covering the first $250,000 in passthrough business income, and lowering the rate to 3 percent on business income over that amount.

- Expanded personal exemptions for those making $80,000 or less.

- The limitation of the $20 personal exemption credit to those with Ohio Taxable Income of less than $30,000 a year.

- Means testing of the senior and retirement income credits at $100,000.

- The repeal of the corporate franchise tax (including also the repeal of the dealers in intangibles tax and the corporate franchise tax that had been paid by financial institutions and their replacement by the new Financial Institutions Tax).

- The repeal of the Tangible Personal Property Tax.

- The increase in the state sales tax from 5.0 percent to 5.75 percent, approved in 2005 and 2013.

- The increase in the cigarette tax from 55 cents to $1.25 a pack included in the 2005 tax package, and then to $1.60 a pack in 2015.

- The elimination of the 10 percent rollback on real property tax for businesses.

- The creation of the Commercial Activity Tax and the increase in CAT minimum tax for many businesses approved in 2013.

The analysis does not include the repeal of the estate tax, which was effective in 2013, and the advent of casinos and racinos that generate tax revenue and payments to the Ohio Lottery (the latter is in part because we don’t know what share of the tax revenue comes from Ohioans). Inclusion of these changes would have further increased the regressivity of Ohio’s state and local tax system, under which lower- and middle-income Ohioans pay more of their income in taxes than the most affluent do. The estate tax was paid on fewer than 8 percent of all Ohio estates, because estates worth less than $338,333 were effectively exempt.

The report does not include the Petroleum Activity Tax implemented in 2014, nor does it attempt to measure the extent to which local tax levies have risen to make up for lost Tangible Personal Property Tax revenue or estate tax. It does not include six other changes to the income or sales tax in the 2013 tax package, or the changes made in 2013 in the homestead exemption and property-tax rollbacks. Nor does it include changes in the municipal income tax, most of which are too new to evaluate. Other changes in exemptions, credits and deductions besides those listed above are not specifically included.

Dollar amounts and percentages in the analysis have been rounded.

For funding that made this work possible, we thank The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, The George Gund Foundation, and The Ford Foundation. We would also like to thank the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, especially Aidan Davis, for research assistance, and Michael Mazerov of CBPP for his input.

[1] See detail on major state level tax cuts since 2005 in Appendix 4.

[2] Schiller, Zach, “The Billion Dollar Tax Break Burning a Hole in Ohio’s Budget,” May 22,2017 at https://bit.ly/2J3Wujo and email from John Charlton, Ohio Office of Budget & Management, Feb. 15, 2018.

[3] Hanauer, Amy.,”State of Working Ohio 2017,” (Figure 13), Policy Matters Ohio, September 2017 at https://bit.ly/2wVLels

4 National Institute for Early Education Research, “State of Preschool 2017” and “State of Preschool 2003,” Rutgers Graduate School of Education at http://nieer.org/state-preschool-yearbooks

[5] Jackson, Victoria, “Number of Ohio’s vital school professionals dwindling,” Policy Matters, Dec. 15, 2016 at https://bit.ly/2suAG9Q

[6] Policy Matters Ohio, “Post 2018-19 budget bite: Affordable College,” October 10, 2017 at https://bit.ly/2smnaVm

[7] Berger, Noah and Peter Fisher, “A Well-Educated Workforce Is Key to State Prosperity,” Economic Policy Institute, August 22, 2013 at http://www.epi.org/publication/states-education-productivity-growth-foundations/

[8] Center for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, cited in Pew Charitable Trust, “Overdose deaths fall in 14 states,” February 22, 2108 at https://bit.ly/2HCufrT. A recent report indicated that opioid-related deaths in several Northeast Ohio counties fell in the first few months of 2018, but it remains a huge public health issue. See Adam Ferrise, “Have opioid deaths in Northeast Ohio finally crested? Evidence suggests yes,” cleveland.com, May 21, 2018, at https://bit.ly/2xBuqmv

[9] Public Children’s Services Association of Ohio, “PCSAO Factbook 2017,” (p.6), at https://bit.ly/2H5jqwT

[10] Ohio Department of Transportation, “Statewide Transit Needs Study,” 2015 at http://www.dot.state.oh.us/Divisions/Planning/Transit/TransitNeedsStudy/Pages/StudyHome.aspx. The study recommended state funding of $120 million a year in 2015, rising to $185 million by 2025.

[11] Patton, Wendy, “Cuts Sting Ohio Localities,” Policy Matters Ohio, December 19, 2016 at https://bit.ly/2MEX4GM

[12] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Who pays: A distributional analysis of the tax system in all 50 states,” Fifth Edition, 2015 at https://itep.org/whopays/

[13] Ohio’s income-tax brackets change each year based on the inflation rate, so originally, this bracket began at $200,000. The $218,250 amount is the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy’s estimate for where the top bracket in the income tax will be for 2018, adjusting for inflation from the 2017 amount of $213,350.

[14] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) modeling for Policy Matters Ohio, April 2018. See Appendix 4 for a list of what was included in the ITEP analysis and additional details.

[15] Besides the rate cuts to the personal income tax and creation of the deduction for owners of passthrough businesses, ITEP’s analysis included a number of other income-tax changes beginning in 2005, including the creation of the state Earned Income Tax Credit and other measures. The full list is included in Appendix 4.

[16] ITEP modeling for Policy Matters Ohio and Policy Matters Ohio calculations, April 2018.

[17] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, at https://www.bls.gov/

[18] Keen, Timothy S., Director Office of Budget and Management, Am. Sub. House Bill 49 Conference Committee Testimony on the FY 2018 and 2019 Biennial Operating Budget, June 22, 2017 at

[19] The $250,000 is the size of the deduction for single taxpayers and those married filing jointly; married taxpayers who file separately can deduct $125,000.

[20] A Legislative Service Commission memorandum of 6/21/2017 (Russ Keller, “Business income deduction estimate using tax year 2015 statistics,” R-132-1320-1) estimated that between $377.5 million and $450.5 million of the estimated state revenue loss goes to the 29,370 taxpayers with business income of more than $250,000. This group represents less than 5 percent of all those getting the deduction but is getting more than a third of the total.

[21]Patton, Wendy, “Wealthy Not Paying Fair Share of State and Local Taxes,” Policy Matters, Apr. 11, 2016, at https://bit.ly/2kC43TQ. Based on modeling by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Numbers in this analysis cover nonelderly Ohioans only, so they are not exactly comparable to other ITEP numbers used in this report.

[22] Young, Cristobal, Charles Varner, Ithai Z. Lurie, and Richard Prisinzano “Millionaire Migration and Taxation of the Elite: Evidence from Administrative Data,” American Sociological Review, Volume 81(3), p. 439, at https://stanford.io/2sm1p99

[23] Hoene, Chris and Gordon MacInnes, “Getting the CA, NJ perspective on millionaire tax,” Commonwealth, May 27, 2018, at https://commonwealthmagazine.org/opinion/getting-the-ca-nj-perspective-on-millionaire-tax/

[24] See, for instance, Michael Leachman and Michael Mazerov, “State Personal Income Tax Cuts, Still a Poor Strategy for Economic Growth,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 14, 2015, at https://bit.ly/2kgGuzh

[25] Honeck, Jon, “A Balanced Approach Promoted Ohio Recovery After Past Recessions,” The Center for Community Solutions, Oct. 9, 2009

[26] Halbert, Hannah, “Job Growth Streak: March Data Show Another Solid Month of Growth in Ohio,” Policy Matters, Apr 20, 2018, at https://bit.ly/2xzDM1I

[27] Halbert, Hannah, “Big Job Gains in May: Ohio Still Trails, But Gets Closer to National Growth Average,” Policy Matters Ohio, June 15, 2018, at http://bit.ly/2ylIGQx

[28] Berger and Fisher, Op. Cit. at http://www.epi.org/publication/states-education-productivity-growth-foundations/

[29] National Institute for Early Education Research, Op.Cit.

[30] Jackson, Victoria, “Number of Ohio’s vital school professionals dwindling,” Policy Matters, Dec 2016, at https://bit.ly/2H4Ygza

[31] Mitchell, Michael, et. al., “A Lost Decade in Higher Education Funding,’ August 23, 2017 at https://bit.ly/2pwkjIT

[32] Institute on Research on Higher Education, 2016 College Affordability Diagnosis: Ohio, University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education, 2016 at https://www.gse.upenn.edu/pdf/irhe/affordability_diagnosis/Ohio_Affordability2016.pdf

[33] Patton, Wendy, “An investment budget for Ohio,” Policy Matters Ohio, January 24, 2017 at https://www.policymattersohio.org/research-policy/quality-ohio/revenue-budget/budget-policy/an-investment-budget-for-a-better-ohio

[34] Institute on Research on Higher Education, Op.Cit.

[35] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax System in All 50 States,” 2nd Edition, January 2003, at https://itep.org/wp-content/uploads/wp2003.pdf

[36] Figures in this paragraph from ITEP modeling provided to Policy Matters Ohio, May 10, 2018

[37] Halbert, Hannah, “Working for Less: Too Many Jobs Pay Too Little,” Policy Matters, April 30, 2018, at https://bit.ly/2K94eRk

[38] Williams, Erica and Samantha Waxman, “States Can Adopt or Expand Earned Income Tax Credits to Build a Stronger Future Economy,” Center on Budget & Policy Priorities, Feb. 7, 2018, at https://bit.ly/2JgGkXn

[39] Marr, Chuck et al., “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds,” CBPP, updated October 1, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3793

[40] For more detailed information on Ohio’s state EITC, see Hannah Halbert, “Ohio EITC Too Weak to Work,” Jan. 27, 2017, at https://www.policymattersohio.org/research-policy/quality-ohio/revenue-budget/tax-policy/ohio-eitc-too-weak-to-work

[41] National Conference of State Legislatures, ”Tax Credits for Working Families: Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC),” April 17, 2018, at http://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/earned-income-tax-credits-for-working-families.aspx

[42] Ibid. Author’s calculation based on information from the NCSL report, excluding tiered EITC amounts and the California, South Carolina and Washington credits. California’s, set at 85 percent, is limited to those with incomes of less than $22,322; South Carolina’s nonrefundable credit, which being implemented for this tax year at 20.83 percent, will eventually be set at 125 percent, and Washington’s 10 percent credit has not been financed.

[43]Ohio Department of Taxation, Tax Analysis Division, “Commercial Activity Tax: Number of Taxpayers and Tax Return Data,” Fiscal Year 2017, Oct. 5, 2017, at https://www.tax.ohio.gov/Portals/0/tax_analysis/tax_data_series/CAT/CAT12FY17.pdf

[44] Marr, Chuck, Brendan Duke and Chye-Ching Huang, “New Tax Law is Fundamentally Flawed and Will Require Basic Restructuring,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Apr. 9, 2018, at https://bit.ly/2HmWnzD

[45] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “The Final Trump-GOP Tax Plan: National and 50-State Estimates for 2019 and 2027,” Dec. 16, 2017, at https://itep.org/finalgop-trumpbill/

[46] According to Child Care Aware of America, full-time care for an infant and a toddler in Ohio’s lowest-cost care ($14,000 a year) would take up 29 percent of the income of a family earning $48,000 a year, while the highest-cost care ($17,6000) would take up 8.8 percent of income for a family earning $200,000 and just 4.4 percent of income of a family earning $400,000. See http://usa.childcareaware.org/advocacy-public-policy/resources/research/costofcare/

[47] Cho, Chloe,“State-by-State: Costly Estate Tax Repeal Benefits Only Few Wealthiest Estates,” September 12, 2017 at

[48] ITEP, “Chained CPI Would Raise Everyone’s Personal Income Taxes in the Future, Would Hurt the Poor Right Away,” Nov 30, 2017 at https://bit.ly/2kcBDD3; see also, Chye-Ching Huang, Guillermo Herrea and Brenden Duke, JCT Estimates: “Final GOP Tax Bill Skewed to Top, Hurts Many Low- and Middle-Income Americans,” December 19,2017 at https://bit.ly/2kMsmOB

[49] Schiller, Zach, “U.S. Tax Law is a Boon to the Affluent,” Policy Matters, April 16, 2018, at https://bit.ly/2J3CsFQ

[50] Parrott, Sharon, et.al., “Trump Budget Deeply Cuts Health, Housing, Other Assistance for Low- and Moderate-Income Families,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 14, 2018 at https://bit.ly/2BZbb7E

[51] Dinan, Stephen, “Ryan defends budget deal, says debt solution is cuts to entitlements,” The Washington Times, February 8, 2018 at https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2018/feb/8/paul-ryan-defends-budget-deal/

[52] “Low-Income Programs Would Bear the Brunt of Ryan Cuts,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 23, 2012 at https://www.cbpp.org/blog/low-income-programs-would-bear-the-brunt-of-ryan-cuts

[53] Bolen, Ed, Cal Lexin, Stacy Dean, Brynne Keith-Jennings, Caitlin Nchako, Dottie Rosenbaum and Elizabeth Wolkomir, “House Agriculture Committee’s Farm Bill Would Increase Food Insecurity and Hardship,” May 10, 2018 at https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/house-agriculture-committees-farm-bill-would-increase-food-insecurity-and

[54] Bolen, Ed, Stacy Dean, Dottie Rosenbaum and Elizabeth Wolkomir, “Senate Agriculture Committee’s Bipartisan Farm Bill Strengthens SNAP and Avoids Harming SNAP Households,” June 11, 2018 at https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/senate-agriculture-committees-bipartisan-farm-bill-strengthens-snap-and

[55]Pryzbyla, Heidi and Jayne O’Donnell, “Analysis: How Trump is unraveling Obamacare piece by piece,” USA Today, October 12, 2017 at

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/10/12/analysis-how-trump-quietly-unraveling-obamacare-piece/754240001/; see also, Andy Slavitt, “The Republican cold war on the Affordable Care Act,” Voc News, May 14, 2018 at https://www.vox.com/the-big-idea/2018/5/14/17350818/affordable-care-act-repeal-attacks-gop-medicaid-preexisting-condition-health

[56] Halbert, Hannah, “Working for Less: Most Common Jobs in Ohio Pay Too Little,” Policy Matters Ohio, May 1, 2018, at https://bit.ly/2tn8pCa

[57] The federal food aid program was implemented in 1964. It is now known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and is administered by the United States Department of Agriculture. It was pre-dated by pilot programs started in the Depression, known as food stamps. See https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/short-history-snap

[58] Poethig Ericka C., “One in four: American’s housing assistance lottery,” May 28, 2014 at https://urbn.is/2srTXss

Tags

2018Ohio Income TaxTax PolicyWendy PattonZach SchillerPhoto Gallery

1 of 22