Fracking in Carroll County, Ohio: An impact assessment

April 10, 2014

Fracking in Carroll County, Ohio: An impact assessment

April 10, 2014

Download four-county summary (4 pp) Download Carroll County summary (2 pp)Download full report (23 pp) Multi-State Shale CollaborativePress releaseThe Multi-State Shale Research Collaborative, of which Policy Matters Ohio is a member, has released case studies examining the impacts of shale oil and gas drilling on four active drilling communities — Carroll County, Ohio; Greene and Tioga counties, Pennsylvania; and Wetzel County, West Virginia.

Executive summary

Shale industry development is shifting the economy, environment and culture of communities like Carroll County, Ohio. Drilling is supporting local businesses, gas stations, hotels and farms. It brings revenue to landowners and some jobs. The story, however, is complicated. Whether it ultimately helps or hurts will be determined by whether money stays in the community, who gets jobs, whether the gas is refined locally, whether local businesses provide services, and what the costs are.

Shale industry development is shifting the economy, environment and culture of communities like Carroll County, Ohio. Drilling is supporting local businesses, gas stations, hotels and farms. It brings revenue to landowners and some jobs. The story, however, is complicated. Whether it ultimately helps or hurts will be determined by whether money stays in the community, who gets jobs, whether the gas is refined locally, whether local businesses provide services, and what the costs are.

Leases: Signing bonuses for landowners ranging from $5 to $5,800 per acre plus royalties temporarily boosted spending, particularly to upgrade equipment, properties, and vehicles. Retail trade in vehicles and parts increased 16.5 percent from 2011 to 2012. Landowners, dismayed by poor lease deals, jointly hired an oil and gas industry lawyer to represent them in negotiations.

Employment: Jobs have been added in Carroll County, but far fewer than promised. Unemployment fell to 8.3 percent from a recessionary 14 percent, but remains higher than pre-recession levels (5.8 percent in July 2007). Statewide, there are fewer than 3,000 shale-related jobs, less that one-tenth of 1 percent of total Ohio jobs. These numbers do not distinguish between jobs to local and out-of-state workers. Companies are largely bringing in out-of-staters, with local workers concentrated in truck driving, delivery, rental, cleaning, restaurant work, laundry, grocery delivery, and rental services.

Buying local: Oil and gas companies buy some supplies locally. Workers are buying vehicles, equipment, truck parts, and services, and going to local bars and restaurants. Sales tax receipts in Carroll County increased 31 percent from 2011 to 2012, especially in mining, auto sales, real estate, accommodation, food services and gas stations.

Housing: Out-of-state workers create demand for temporary housing. The hotel in Carrollton has been solidly booked for two years, there are plans to build a new hotel, campgrounds are full, and the rental market has been stimulated. For owners, this means increased rental income. Retail trade for building materials and garden equipment increased 28 percent from 2011 to 2012. But spiking rents often exceed what local residents can afford.

Traffic: Hundreds of heavy trucks carry gravel, equipment, water, chemicals, sand, and waste, creating congestion, maintenance costs, accidents and emergency service costs. Congestion creates a problem for police, road workers, emergency personnel, snow removal trucks and school buses. One accident killed a trucker and a community member, and the higher rate of accidents has quadrupled calls and doubled incidents for the sheriff.

Wastewater: Fracking fluid contains sand and chemicals, some toxic. Ohio allows some fracking waste to be dumped in landfills, creating potential downstream pollution. In 2012, 14.2 million barrels of fracking waste were injected in Ohio’s nearly 200 disposal wells, more than half from states with better regulation, like Pennsylvania and West Virginia. The group Carroll Concerned Citizens worries that fluids could contaminate drinking water. In nearby Youngstown, a man was indicted for dumping 20,000 gallons of fracking waste into the Mahoning River.

Worker safety: Industry jobs are difficult, dangerous, involve long hours and often come without insurance. Shale jobs have come with an increase in fatalities. Nationally, oil and gas fatalities hit a record high in 2012, increasing 23 percent from 2011. Deaths came from transportation incidents, blunt objects, fires and explosions. In Carroll County, people have been killed in car accidents and by on-site drilling. Uninsured workers and their families often seek uncompensated care from hospitals.

Health and environment: In Trumbull County’s Weathersfield Township, Halcon Energy flared a gas well for two weeks near a residential neighborhood. The flame created a bright light all night, made noise at a decibel level similar to a tornado warning, and emitted noxious fumes. Development affects the ecosystem. Six slurry spills in the first quarter of 2013 smothered plant life and caused “significant degradation” of wetlands. Fracking and wastewater injection have caused earthquakes.

Future: Lack of clarity about what to expect makes it difficult for officials and businesses to plan. One impediment to housing and business development is limited access to central sewer and water infrastructure. The county is studying expansion but if the shale boom does not happen as anticipated, the cost of expanding infrastructure will be borne by existing users.

Jobs and training: Although unions say they have qualified local apprentices who could do the work, the industry often hires from out of state. Schools and colleges are adding capacity. The Superintendent of Carrollton Village School District wants to build a high school Energy Resource Academy and Stark State, roughly 35 miles away, is developing an industry-tailored associate degree and certification program. The Ohio Department of Job and Family Services in Carroll County is helping with certifications for truck driving and other jobs. Recent cuts in Workforce Investment Act (WIA) funds make it difficult for the local agency to meet needs.

Government revenues: Increased economic activity generates revenue from sales taxes ($2.55 million in 2012 from $1.67 million in 2009), recording deeds, mortgages, leases, and fuel taxes. Last year, the county had a surplus, enabling a much overdue salary increase and better funding of increased dispatch services to meet shale-related needs. Local governments can benefit: the Carrollton school district, for instance, received a one-time signing bonus of $400,000. The county used proceeds from to renovate the courthouse.

Recommendations

The economic benefits of fracking fall far short of what was promised and come with costs to safety, the environment and the community. Ohio should increase its severance tax to 5 percent and use proceeds to maximize benefits and minimize costs. The tax should be used first for industry oversight and regulation and for covering community costs. The full report recommends:

- Putting in place additional taxation for a permanent fund;

- Forming local taskforces to identify issues, consider solutions, and open dialogue in the community;

- Monitoring, by the state, of water quality and other environmental health issues;

- Prohibiting of flaring and new pollution control requirements; and

- Strengthening policies to require local hiring and provision of health insurance.

Fracking in Carroll County

Introduction

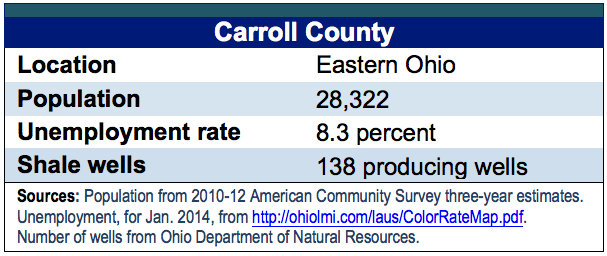

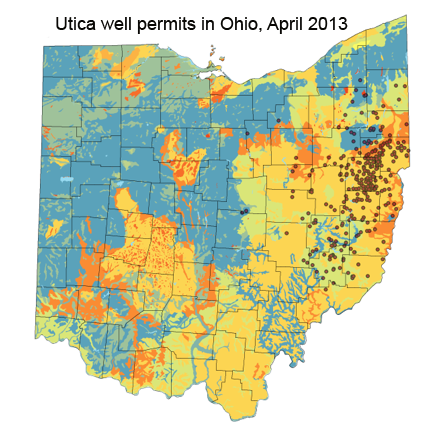

American production of oil is rising faster than it has since the 1950s, putting the U.S. on track to becoming the world’s biggest oil producer, in large part due to shale development.[1] In the Midwest, shale development is occurring in two geographic formations, the Marcellus and Utica shale found largely in New York, Pennsylvania, Eastern Ohio, and West Virginia. Ohio lags behind Pennsylvania and West Virginia in industry development. At the end of 2012, Ohio had 270 shale wells, while Pennsylvania had 6,245 drilled wells and West Virginia 2,120.[2] The number of wells drilled in Ohio more than doubled in 2013, but there are still far fewer than in Pennsylvania and West Virginia. However, activity in Ohio continues to increase.

American production of oil is rising faster than it has since the 1950s, putting the U.S. on track to becoming the world’s biggest oil producer, in large part due to shale development.[1] In the Midwest, shale development is occurring in two geographic formations, the Marcellus and Utica shale found largely in New York, Pennsylvania, Eastern Ohio, and West Virginia. Ohio lags behind Pennsylvania and West Virginia in industry development. At the end of 2012, Ohio had 270 shale wells, while Pennsylvania had 6,245 drilled wells and West Virginia 2,120.[2] The number of wells drilled in Ohio more than doubled in 2013, but there are still far fewer than in Pennsylvania and West Virginia. However, activity in Ohio continues to increase.

Drilling is shifting the economy, the environment and the culture of some rural communities in the region. Carroll County has been the most active Ohio county for fracking, with more than half the state’s producing wells.[3] For Carrollton, the heart of rural Carroll County, oil and gas industry development has already brought about substantial economic change. The economy there struggled long before being hit hard by the recent recession. Population was stagnant and young people were leaving because there were few local opportunities. Local economic development efforts proved largely futile and there were concerns that the county’s economic center was on its way to becoming a ghost town. Now oil- and gas-related companies are coming to the county without being solicited, and industry activity is supporting locally owned businesses, gas stations, hotels and farms. Producing wells also bring revenue from signing bonuses to landowners for mineral leases, the potential for royalties and some new jobs.

The story, however, is complicated. Shale development in oil-rich areas in the West created unanticipated negative impacts and costs to local governments and the community as a whole. In rural Sublette County, Wyoming, for instance, much of the industry employment has been transient with more than half the workers coming from elsewhere. The influx of transient workers increased pressure on limited housing supplies in remote areas, causing rents to rise. In addition, the crime rate increased, roads deteriorated from all the heavy trucks, and the community experienced water issues.[4]

The overall economic impact from shale development in Ohio – positive or negative – will be determined by how many of the dollars stay in the community, who gets the jobs and whether they are temporary or permanent, whether wages and royalties are spent within the state, whether local businesses provide products and services, whether gas is consumed locally, and what the infrastructure, health, human service, and ecological costs to the community are. [5] To develop a more comprehensive assessment, this report takes a closer look at both benefits and costs of drilling activity in Carroll County, Ohio. It is designed to help local government officials and community stakeholders in neighboring counties anticipate what to expect as activity unfolds in their own communities. We hope to shed light and promote discussion around maximizing benefits while minimizing costs of shale development with public policies that can help balance these interests.

Methodology

Policy Matters worked with partner organizations in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, as part of the Multi-State Shale Research Collaborative (found at www.multistateshale.org/), to conduct four in depth case studies in affected counties across our respective states. Policy Matters Ohio conducted the study on Carroll County. We chose to focus on Carroll County because it is by far the most active drilling county in Ohio and the most likely to have experienced impacts. The Multi-State Shale Collaborative developed a shared methodology to be used for each county in our respective states. We started with a review of existing literature on shale development impacts in places farther along in industry development. Armed with this information, which gave us insight into what to look for in our own counties, we set up a series of interviews with local officials and residents likely to have detailed information related to impacts seen elsewhere. Where possible, we supplemented our interviews with quantitative data, although because industry development is relatively new in Ohio (and also because some data sources do not provide information at the county level), there were limited data available for use in the Carroll County case study. Below is the list of local people we interviewed for the Carroll County case study. We are grateful for their time and candor.

Interviewees

- Bill Newell, Owner of Newell Realty and Auction, Barb Newell, Office Manager,and Bonnie Newell, Broker, www.newellrealtyandauction.com/.

- Vince Carter, County Manager of Carroll County Garage

- Robert Wirkner, Carroll County Commissioner-Vice-President,

- Dr. Dave Quattrochi, Superintendent Carrollton Exempted Village Schools,

- Ralph Castellucci, Director, Carroll County Environmental Services,

- Nick Cascarelli, Health Department Commissioner

- Heather Maher, Director of Environmental Health, Health & Environmental Health

- Deb Knight, Assistant Director of ODJFS, One-Stop Employment Services Agency

- Kate Offenberger, Director of Carroll County Department of Jobs and Family Services

- Mike Guess, Owner of Guess Ford auto dealership http://guessford.dealerconnection.com/staff/

- Kim Mills, Manager Ace Hardware Store, 22cd year in business

- Ken Kenst, Public Service and Safety Director, City of Salem, Ohio

- Paul Feezel, Carroll Concerned Citizens

Oil and gas leases: Signing bonuses and royalties

One of the first signs of drilling activity in Carroll County was the influx of a large number of “landmen” – representatives of oil and gas companies sent to buy or lease local sub-surface mineral rights or purchase land outright. Early in the process, which accelerated in mid-2011, company representatives flooded the courthouse recording office to research property records or record new deeds. The Carroll County Recorder’s office recorded 1,781 leases in 2011 compared with 495 in 2010.[6] Carroll County, still using dial-up Internet service at the time, was not equipped for this level of traffic. Chesapeake Energy, the most active oil and gas company in the county, spent $200,000 to help digitize county property records.[7]

An estimated 95 percent of Carroll County sub-surface rights have been bought or leased by oil and gas companies. Oil company representatives offer local landowners signing bonus incentives and a percentage of on-going royalties in exchange for their property rights to sub-surface minerals. The size of the bonuses and level of on-going royalties, as well as most other lease terms, are largely determined in negotiations between oil and gas company representatives and property owners. However, federal law mandates that no less than 12.5 percent of royalties of oil and gas sales go to the property owner. As word of mouth travels about the terms of previous deals, property owners who hold out seem to get better deals. In Carroll County, companies went from offering $5 per acre signing bonuses to $1,500, then $3,800, and all the way up to $5,800 per acre signing bonuses plus 20 percent gross royalties. Tom Stewart, Vice President of the Ohio Oil and Gas Association, said companies offered Noble County landowners bonuses of $2,000 to $5,000 per acre to sign leases.[8]

Poor lease deals could detract from benefits. According to interviews of local residents and public officials in Carroll County, a number of deals were made and terms negotiated for rates locals should or would not have accepted with a better understanding of the opportunity, the terms, or access to a decent lawyer familiar with the industry. In the early stages of industry development, some residents leased their rights for as low as $10 per acre in signing bonus compared to some that later went for as high as $5,800 per acre.[9] Recent research conducted by ProPublica found terms of the lease may dictate that severance taxes and other costs of drilling be subtracted from the local owner’s share of royalties. Many lessors have no way to get information about the production on their land or answers to questions: Many leases don’t allow for financial audits, and those that do may require landowners to pay tens of thousands of dollars to get one. If there is a discrepancy found in an audit, there is typically a provision for arbitration in the lease, a route that costs landowners tens of thousands of dollars to pursue. All this has to happen before a short statute of limitations expires along with the legal right to dispute the amount received.

Over time, landowner groups formed in Carroll County to negotiate group leases with better terms in order to get the most value for the group. A group of Carroll County landowners, dismayed by the practices of some natural gas companies and the impact on landowners, formed a group and hired an oil and gas industry lawyer from Canton to draft a lease and represent them in negotiations.[10] The landowner group accepted bids from various companies and secured a deal with a $2,250 per acre signing bonus, 17.5 percent gross royalties, and protections for water, crops, roads, pipelines, and well locations.[11] Since then, other landowner groups have formed to secure even better deals, some garnering signing bonuses as high as $5,000-$6,000 per acre.

Old claims to mineral rights are emerging. Some property owners are finding that old mineral rights leases, signed many years ago and long forgotten, are causing unexpected problems. Mineral rights transferred up to 100 years ago are being dug up and resold by third parties, taking away the right of local landowners to negotiate a new deal for themselves. One group of Ohio landowners that signed away oil and gas rights some time ago, and then learned that the company resold the rights for a much higher figure, filed a class-action lawsuit claiming the company failed to develop the land in a timely manner.[12] The Monroe County Common Pleas Court judge agreed and voided the leases covering more than 20,000 acres of land. The case has been appealed.

Local property owners who resist signing leases voluntarily may find themselves at the mercy of mandatory pooling and forced unitization if they hold out too long (the state approved eminent domain of mineral rights). An oil and gas company that has leases covering 65 percent of a landowner’s neighbor’s property can petition the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) to create a “drilling unit” that includes the objecting landowner’s mineral rights.[13] Thirty-eight states have similar laws.[14] Ohio’s mandatory pooling law was put into place in 1965, but was used only twice until recently. In 2012, 70 acres were unitized into a single drilling development over the objection of 23 owners.[15] Since then ODNR has received 11 requests – four approvals, five pending, and two resolved outside the agency.[16] As a result of the increased activity, ODNR revised its rules for unitization to make it easier for oil and gas companies to unitize.[17] ODNR will grant a mandatory pooling request if the driller can show “substantially more oil and gas from the pool than would be produced without access to that land, and the added value of that extra oil and gas makes the whole operation cost effective.”[18] Mandatory pooling has created tension in Carroll County, with neighbors pressuring neighbors to sign on so they can all benefit from joint leases encompassing multiple properties. According to interviews, some property owners buckle to the pressure and sign lease deals rather than become subject to mandatory pooling. Ohio’s decision-making process lacks any formal mechanism for considering the rights and wishes of the affected landowner.

Productivity of shale oil wells falls sharply after the first year, lowering return on investment and royalties compared to traditional oil wells. Production decline curves show that after an initial spike in the flow of oil, hydraulically fractured wells experience a rapid decline in production of 40 percent or more after the first year, another 35 percent decline after the second year, and a decline rate of 30 percent in the third year.[19] By year five, the decline rate is 20 percent. In 2012, of Ohio’s 85 shale wells in production, only three were producing hydrocarbons for at least 300 days, and 18 were in production for less than a week.[20] In essence, this means rapidly declining royalties as well. Between rapidly declining revenues and the high costs of shale drilling compared to conventional drilling, the rate of return on shale investments, and ultimately landowner profits, are lowered.[21]

Some oil companies minimize royalties paid to landowners.[22] Manipulation of costs and other data results in oil and gas companies keeping dollars that would otherwise belong to the local landowners. Another method oil and gas companies use to minimize landowner royalties is deduction of expenses. This is allowable under many leases, albeit controversial. In some cases, oil and gas companies are withholding as much as 90 percent of the landowner’s share for unspecified “gathering expenses.” [23] In other cases, money is withheld for deductions of unauthorized expenses without even telling the landowner. In dozens of class action lawsuits, plaintiffs allege they could not make sense of deductions or companies were hiding charges. Pro Publica determined that landowners received less in royalties than expected based on sales.[24] In some cases, they are paid virtually nothing at all. One method of minimizing the local landowner’s share of royalties is by hiding the full value of resources from landowners. Some fuel recovered from wells is used for drilling operations, so never technically sold, enabling oil and gas companies to avoid paying royalties and tax on the fuel. Another related tactic is for companies to barter fuel for services received off the books or to set up subsidiaries and limited partnerships to whom they sell the gas at lower rates. Royalties paid to landowners are based on the lower price garnered from the initial transaction. Then the subsidiary or limited partnership turns around and resells the same gas at higher rates. Since 2011, the U.S Department of the Interior recouped $4 billion because of more than a dozen instances of oil and gas companies willfully deceiving the government on their royalty payments.[25] Typical landowners, however, lack the resources to investigate oil company practices. Landowners have to file costly court case just to get the information needed via the court’s discovery process.[26] And even if landowners win, they only get what was already owed them since the bar is set high for punitive damages.

Local economic activity

Carroll County residents used some of their proceeds from signing bonuses to buy new equipment or make needed repairs. Much of the money received from signing bonuses went back into the local economy. For instance, farmers used these funds to upgrade equipment and properties, buy new roofs, barns, and tractors that they have wanted for some time but could not afford previously. Following the initial bout of lease signings, there was also a burst of new and used car and truck sales. In 2010, one car dealer in Carroll County experienced a 40 percent increase in sales. From 2011 to 2012, retail trade in motor vehicles and parts in Carroll County increased 16.5 percent, according to sales tax data. Related sales tapered off once most of the land in the county was leased and initial signing bonuses were spent.[27]

Shale development appears to be a boon to some local farmers. For some time, small farms have been going out of business, and big farms started to go that way as well. Since technology allows drilling in several directions from one location, there can be multiple wells on one well pad rather than several wells scattered throughout a property as with traditional drilling. Farmers may lose five acres between widening of the road, the well pad, and the removal of topsoil surrounding the well pad, but the rest of the farm remains workable.

Some local government and non-profit organizations also benefit economically from leasing mineral rights. The Carrolton school district, for instance, received a one-time bonus payment of $400,000 for what will likely be between six and eight oil wells. The funds from the signing bonus helped cover a budget gap created by cuts in state and federal funding. For nearly $2 million, the county government leased mineral rights to its public lands, using some of the proceeds to do a long overdue renovation to the County Courthouse.[28] In order to purchase a new fire truck, Carrolton Village Council plans to sell part of gross profits from oil and gas leases, one-quarter of its 20 percent in expected royalties, for a one-time payment of $555,000.[29]

Companies buy local. Oil and gas companies buy some supplies locally and patronize local restaurants and bars. Industry workers are buying vehicles (new white pickup trucks), oil field equipment, truck parts, and mechanical services. As mentioned above, a boost in spending has also been attributed to receipt of signing bonuses from local residents leasing their mineral rights. In total, sales tax receipts in Carroll County increased 31 percent from 2011 to 2012, with particularly large increases in activity related to mining, retail auto sales and services, real estate and rental and leasing of property, indicating solid growth in economic activity in the county as well as increased revenues for local government operations.[30] The greatest increase in sales tax revenues came from retail trade activity related to county motor vehicle and parts dealers with its 16.5 percent in Carroll County from 2011 to 2012, as mentioned above. While most of the increase in car sales comes from landowners with signing bonus money, between 15 and 20 percent of auto-related sales have been attributed to oil and gas operators. Dealers and local mechanics are being employed to service these vehicles as well.

Hotels, restaurants, bars, and gas stations are also seeing an increase in business. Economic activity related to accommodation and food services increased 20 percent from 2011 to 2012, while gas station sales increased 60 percent, according to sales tax data.[31] Sales at the local Ponderosa, for instance, increased by 10 percent or more each year for the past two years. Donna’s Deli is also busy.[32] At the local gas station, workers fill up their gas tanks and then spend $20 or more on snacks to take to the oil field with them. The local McDonald’s often has a morning line out to the road. Oil and gas industry activity has also generated a moderate boost in sales at the local hardware store, when sales at hardware stores elsewhere have largely been flat. The store is selling kerosene and propane to workers living in RVs, large galvanized pipes for drilling purposes, fire retardant clothing and steel toe boots, and abrasives for sanding equipment before they put it together. The store also hired a point person to research and address special needs of the industry. Increased car and truck sales and services led one local auto dealer to hire four to five new employees, and the local Ponderosa brought on ten new employees since the upswing. Local businesses that are experiencing increased sales have more cash on hand for repairs. Ace Hardware and Gas, for instance—a third-generation, locally owned gas station and hardware store – expanded recently, something it had wanted to do for 20 years. The store consolidated on one site, including storage facilities, and expects to increase productivity.

Nearby communities benefit from positive spillover. In areas surrounding Carroll County, hotels and business parks are filling up, bringing ancillary economic benefits to communities without wells. In neighboring Columbiana County, Salem is selling water to the shale industry and a former brownfield site has become a site for storing fracking tanks. The city also has seen interest from developers. As in Carroll County, this increased interest follows a big hit the community took during the recession when several local plants shut down and moved elsewhere. Unlike Carroll County, however, Salem has the water and wastewater infrastructure to accommodate more housing and business development. The county is anticipating increased drilling activity once a connecting pipeline is built. Over half of government-owned property is already leased, with proceeds from the signing bonus used to pay off bond obligations and support a small grant program. Based on local interviews, sentiment is generally positive toward development, although there is recognition of the need to ensure that local residents are trained for the work and to have hotels and housing to accommodate both workers and residents.

Employment impact, transient workers

Trends in employment in Carroll County have been positive. Residents are more able to find work and unemployment is down to 8.3 percent from a high of 14 percent during the recession, although still higher than pre-recession levels (5.8 percent in July 2007).[33] Ohio shale gas has not yet lived up to jobs promised, though, and Carroll County residents are tentative about future prospects. Shale-related employment in Ohio on the whole has been relatively minor – fewer than 3,000 jobs, less than one-tenth of 1 percent of Ohio’s total employment.[34] The data do not distinguish between jobs given to local residents and those that go to out-of-state workers – so some of these 3,000 jobs aren’t going to Ohio residents.

In April 2013, the Cleveland Plain Dealer’s Politifact rated the Ohio Oil and Gas Associations claims of 40,000 new Ohio jobs “pants on fire” and a misrepresentation of the facts. Over half the number of jobs identified by the industry were existing jobs, such as in food services, health care and real estate.[35] There are a number of workers operating on each drilling pad, but these units are largely self-contained, with the workers following the drilling pad as it moves across the country. Each rig is like its own little city with workers following the rig. According to interviewees, Chesapeake doesn’t hire many people locally except for positions such as security guards, or mechanics to service trucks. When these companies do hire locally, it tends to be those already employed. Several local firms interviewed had lost employees to the oil and gas industry (which pays higher wages). In turn, other local residents get hired to backfill these jobs, which is good for those workers and the economy. In early 2013, union and non-union workers protested oil and gas company hiring processes in Carrollton, objecting to the fact that local workers weren't getting oil- and gas-related jobs.[36] The Laborers District Council of Ohio said that county residents were willing, able, and trained to do the work, but that companies were largely bringing in out-of-staters to build pipelines and processing plants, citing one company, the Willbros Group, which brought in 600 Texas construction workers.

Industry jobs are difficult, dangerous, and often don't provide health insurance. Oil and gas jobs require long hours, and fatigued workers and dangerous conditions can be a lethal combination. As a result, job gains have come with an increase in workplace fatalities. Nationally, oil and gas fatalities increased 23 percent from 2011 to hit a record high in 2012.[37] An in-depth study of work injuries in the industry attributed 41 percent of fatalities to transportation incidents, 25 percent to contact with blunt objects and equipment, and 15 percent to fires and explosions.[38] Another issue is high worker exposure during drilling to airborne silica, which can cause lung disease, inflammation, scarring and possibly lung cancer.[39] Hundreds of thousands of pounds of sand for shale drilling is moved, transported and blended, exposing workers to dust that includes high levels of respirable crystalline silica.[40] In Carroll County there have been at least two transportation incidents causing work-related fatalities.[41] There have been on-site drilling fatalities as well. In February 2013, an Ohio worker died from massive blunt impact injuries after being struck by drilling equipment as it swung around the well platform; another worker was injured.[42] In Coshocton County, a Caldwell man died from head injuries after he slipped and fell from a platform.[43]

Despite dangerous conditions, many of these jobs do not come with health insurance, which creates an issue for communities if workers or their families show up at local hospitals seeking care. Ecosystems Research Group identified substantial fiscal impacts for county government in Sublette County, Wyoming, which funded the operation and expansion of medical clinics in the region, and reported a rise in the number of patients without health insurance at the clinics that coincided with the expansion of oil and gas development.[44] In Pennsylvania, a community-owned hospital located in Lycoming County Pennsylvania attributed the loss of $750,000 to the rise in uncompensated care resulting from subcontractors working on Marcellus shale drilling operations in the region.[45] A 2013 study by The New York Times found emergency room visits to a county hospital in North Dakota increased 400 percent while the hospital’s debt increased 2,000 percent (by $1.2 million), largely because of unpaid bills.[46]

The biggest demands for local workers are for truck driving, delivery, rental and cleaning. Most of the local jobs created have not been in the oil and gas industry, but in supportive industries like truck driving, delivery, rental and cleaning services. Oil and gas workers who work long hours – sometimes 12-hour shifts for 14 days in a row (with one week off during which they often leave town) – and often need help with household chores. Demand for services include cleaning, laundry, dry cleaning, grocery delivery, and rental services. One former bank appraiser opened a concierge business to coordinate and provide these services. Restaurants are also hiring, albeit mostly for lower-wage jobs.

Construction of midstream facilities and pipelines are generating investments and local jobs. Local workers in the skilled trades are starting to see an increase in work due to manufacture and installation of pipelines and midstream processing centers.[47] Investments in midstream processing facilities should also create more permanent local jobs. For instance, the first $400 million processing plant phase in Columbiana County of a $900 million natural gas project is complete, easing a bottleneck that has kept production from getting to market. The first phase employed nearly 1,700 construction workers, 60 percent of whom were said to be Ohio natives.[48] The project is expected to employ 50 people permanently to operate the facilities, and another 15 to operate a related rail terminal in Harrison County. The fractionation plant will separate natural gas liquids from natural gas methane delivered via pipelines across Carroll. Methane will then go to an interstate pipeline, while the liquids will be sent to Scio in Harrison County, where they will be separated by heat into propane, butane and ethane and loaded on up to 90 rail cars per day for transport.[49] Plans have been announced to lay 80 miles of pipe to transport water from the Ohio River to Ohio and West Virginia drilling sites, adding to a growing number of water pipelines, in order to reduce two-thirds of the transportation costs from water delivery trucks.[50] Nearly five million gallons of water from the Ohio River would be sent per day by pipeline to pools of water and piped to pads.[51]

Housing market: Benefits and costs

The influx of out-of-state workers has increased demand for temporary housing. Few of the workers buy property; most stay in hotels or lease space. As a result, the local hotel in Carrollton has been solidly booked for the last two years. There are also plans to build a new hotel nearby.[52] The campgrounds are full of oil and gas workers with big campers. One lake resort came back from the brink of demolition because of demand,[53] and empty lots are being turned into RV sites. The Office of Environmental Health in Carroll County gets calls from locals asking how many RVs they can have on their property. Locals are told that if they want to rent to more than three RVs, then it would be considered an RV Park and they must comply with regulations. The county requires properties to have a septic tank, with the rule being one residence per septic per parcel. However, at least one property in the county has a trailer parked next to a port-a-john. The state recently created the Ohio mobile commission to oversee mobile home parks and RV sites.

High demand has stimulated the rental market, benefiting owners of rental properties but burdening local families who rent. Oil and gas workers looking for permanent housing are able to pay higher than market rent because of per diem payments from employers. For rental property owners, this means increased rental income, but it also changes the nature of the rental market. Oil and gas workers want rentals furnished and equipped with items like pots and pans, televisions and cable. To cater to this market in the last year and half, Newell Realty, a small, locally based family business started in 1943, has begun offering and managing rental properties. A second-hand furniture market is developing. Furniture that once went for $5 now sells for $50, according to one resident. There is a significant amount of property rehab, with residents fixing homes for rental. This brought an increase in business to the local ACE hardware store. Retail trade for building materials and garden equipment and supplies increased 28 percent from 2011 to 2012 in Carroll County, according to sales tax data.

Large housing stipends for oil and gas workers and a limited supply of housing in Carroll County have driven rental prices higher, which means increased rent for local families. These prices exceed what many residents can afford based on local wages. Rents doubled, tripled, and in some cases even quadrupled, according to locals interviewed. Prior to development, these sources said that a family could rent a place for between $400 and $450. Now, a two-bedroom goes for between $1,000 and $1,200, and a three-bedroom between $1,500 and $1,800. In some cases landlords can get up to $3,000, depending on how many oil and gas workers can fit (one interviewee mentioned a home with as many as eight people in it). This means increased income for owners of rental properties, but it puts strain on local renters. Since local incomes have not increased commensurately, housing that was once affordable to moderate-income families no longer is.

As landlords raise rents, many local residents can no longer afford to stay in their homes. There are anecdotal stories in the community of tenants expressing concern about being evicted or not getting lease renewals under comparable terms. When families look for new place, they may be told to stay where they are, as they may only find lower quality housing, such as a mobile home, or they may have to move to a neighboring county. Rent increases are disproportionately impacting seniors and people with disabilities on fixed incomes. Some older residents who are ready to downsize from a farm to a property in town have found nothing available. In Carrollton, there is one low-income senior housing development with government assistance, and a center for low-income elderly that offers a room with a bathroom and access to health care. Elderly people in need of assisted living have to go to other counties where they are not able to walk to visit the people they know. Local families, especially young families and single mothers, are also having a hard time. There are neither metropolitan housing services nor Section 8 housing vouchers in Carroll County. Habitat for Humanity has built a few local homes but there is still a need for more affordable housing. Some low-income families get very modest rental assistance via the Prevention, Retention and Contingency (PRC) fund. Last year, the county department of Jobs and Family Services increased PRC payments to $365 per year. However, this amount is not nearly enough to cover the increase in housing prices.

The 2013 report, The Impact of Shale Development on Housing in Carroll County, prepared by Ohio University, The Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs, and the Coalition on Homelessness and Housing (COHHIO) assessed the rental housing markets in shale counties and the changes that have occurred over the past year. [54] The group determined the shale boom has created a shortage of affordable housing in eastern Ohio but that communities are reluctant to invest in new housing, water and sewer infrastructure because the need could be only temporary.[55] The research group deemed modest increases in the development of hotels, senior and low-income housing may be warranted. [56]

Properties that can be used for rental purposes sell quickly. Landowners are hesitant to sell land now due to shale-industry development. When fixer-uppers come on the market for sale as rental properties, they go quickly and their values have increased. Investors are also looking at properties. In November 2012, a 162-acre farm was split into 12 parcels and quickly sold. A crowd of investors was interested even though the seller kept mineral rights.

Proximity to drilling pads is a concern for prospective property buyers and to lenders. In a study looking at residential property sales and well locations in the Northern San Juan Basin of Colorado from 1989 to 2000, researchers found a 22 percent net reduction in the value of property with wells.[57] A 2009 Integra Realty Resources study for the town of Flower Mound, Texas, found a similar decline in property values dependent on the distance from natural gas well sites ranging from three percent to 14 percent based on the method of comparing sales.[58] The Colorado School of Public Health made a similar determination in its economic assessment of oil and gas drilling in Battlement Mesa, Colorado, stating "[n]atural gas development causes a decline in property value, especially during the development phase of the project and land values partially recover when the development phase of a project ends... Land values effects will be impacted by how well other concerns, such as air emissions, traffic, noise and community wellness, are mitigated."[59] In Carroll County, sellers are starting to separate mineral rights from the sale of the property itself. While sellers can get more than $3,000 per acre for mineral rights, there is reason to believe property values, minus mineral rights, may decrease over time.

Concern over properties with oil and gas leases can affect their marketability.[60] Concerns related to the effect an oil and gas lease will have on the property value, such as exposure of residents to health and safety hazards and limitations the lease might have on residential use of land, can reduce the marketability of a property and expose primary and secondary lenders like Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae to greater risk of default. National lenders are becoming more cautious about fracking’s impact on property values.[61] Some are starting to require that property appraisals include the presence of a shale gas well or impoundment lake on or near the property, and in some cases are refusing to lend if drilling activity is on or near the property. FHA guidelines prohibit financing of properties within 300 feet of an active or planned drilling site out of concern for the health and safety of occupants. If the property is subject to smoke, fumes, offensive noises and odors, it becomes ineligible for FHA financing. Some mortgages include a rider prohibiting the leasing of oil and gas rights. Also, some homeowner policies do not cover properties where drilling takes place.

Road and traffic costs, railroad investments[62]

Another of the first indicators of oil and gas industry development in Carroll County, and one of the most visible signs, is a significant increase in traffic, particularly heavy trucks. Oil and gas workers often drive signature white trucks. Hundreds of trucks carry materials to and from drilling wells, including gravel, equipment, water, chemicals, sand, and waste. Much of the oil and gas produced is transported by truck to railcars or pipelines leaving the state. North Dakota, a state heavy with shale development, saw a 35 percent increase in its transportation and warehousing industry in 2012.[63]

More traffic, but “livable.” In Carroll County, traffic gets heavy, especially in the center of Carrollton. Four state routes come together in Carrollton square, and the point of convergence is the only way through Carrollton, so there is often a line. For most people, increased congestion means it takes longer to get through town and gas stations have lines. The congestion is a problem for police, road workers, emergency service personnel and school buses. The school district changed its bus routes to avoid traffic. In some cases, drilling trucks have impeded the progress of trucks clearing snow and ice. Recently, Carrollton Village Council was asked to consider changing parking rules for oversized trucks, restricting them to one side of square.[64] When large trucks are parked on both sides it becomes difficult for residents to drive between. The Council was also advised of a need for crossing guards at major intersections due to concern for the safety of children and elderly who are unable to cross streets fast enough to avoid large trucks driving through the village.

Increased traffic leads to increased road costs. The increased traffic and heavy trucks causes greater wear and tear on roads that were not designed for constant truck traffic the fracking process requires. Road costs for Carroll County increased substantially.[65] Given the heavy truck traffic, a district engineer also took a look at the county’s 63 bridges to ensure they could handle the increased load. Fortunately, the county’s bridges were deemed in good enough condition to withstand the additional stress.

Crashes in Carroll County have spiked, particularly those involving heavy trucks.[66] Large trucks have difficulty navigating the curvy, hilly and narrow roads in rural communities, and some of the oil and gas industry’s long trucks have trouble negotiating tight turns. Nearly all of Carroll County’s 305 lane miles are rural two-lane roads, including county and township roads and state routes; the widest road in the county is a short three-lane route with a turning lane in the middle. Inadequate training and fatigue may also contribute.[67] Before shale development, there might have been one or two accidents a year involving semi-trucks, and five years might pass without a rollover incident. Over the last year, however, there have been several large vehicle rollovers in the county; a trucker and a community member recently died.[68]

Increased accidents hike workload for sheriff, require more firefighter and hazard training, despite budget cuts. Over the past two years, reported traffic incidents have doubled and calls to the sheriff have quadrupled. The Ohio Emergency Management Agency, in partnership with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, the Carroll County Sheriff’s office, local firefighters, and the Ohio State Highway Patrol initiated emergency response exercises.[69] Increased workload requires increased staffing. EMS staff now work extra shifts. Carroll County identified a need for an assistant director of emergency management and additional deputies.[70]

For the county Department of Transportation, this means more unplanned work, road maintenance, and permit processing. ODOT is not called for minor accidents, but if the road needs to be closed, ODOT is brought in on occasion for traffic control. Ultimately the department inspects for road and guardrail damage, and makes the area safe until equipment can be removed. Truck accidents can damage large chunks of road, and require guardrail repair, particularly if the truck rolls over. There have also been instances of spillage – oil in one case – requiring clean up. After an accident, the county bills for any work that has to be done, which then typically goes to an insurance company. However, sometimes trucks cause damage and keep going, and the county doesn’t learn about it until later. In one location, the same stop sign has been knocked down three times. The county ODOT added a second transportation manager, transferred from another county, who focuses on processing special permits for overweight, over-height, and over-width vehicles to access state highways and right of ways.

The safety of the Ohio Department of Transportation workforce is a concern. No issues have been reported, but ODOT has set up an internal website detailing the location, number, activity level and routes of delivery trucks. With this knowledge, ODOT can try to avoid work there if possible. Companies differ in their willingness to coordinate with officials.

Railroad companies are upgrading.[71] Trains are moving sand east from Illinois and Wisconsin for shale drilling in Ohio, and condensate, butane, propane, and other hydrocarbons west out of the state. While pipelines are used to move gas to processing centers, railroads can move it from processing centers to further points in the market since railroads have more connection points than pipelines. To better accommodate industry needs, rail companies are purchasing new locomotives, upgrading stretches of track, and developing multi-modal rail yards. Halcon Resources announced plans to build a $70 million oil storage and 20-railcar loading facility in Lordstown's Ohio Commerce Center, to ship oil via rail to the Gulf and East coasts.[72] Fifty construction jobs are expected to be created during the construction phase, with another 30 full-time permanent positions needed to operate the terminal and three condensate stabilizers that convert condensation from natural gas liquids into marketable products.[73]

The Ohio Department of Transportation is undertaking studies. The state hired a pavement engineer expert to do five-year predictions and is studying traffic related to each well and pavement life cycles. In addition, Ohio requires Road Use Management Agreement (RUMAs), developed because local officials wanted guarantees that Township and County road systems would be maintained.[74] ODOT then worked with ODNR’s Oil and Gas Division to require a RUMA prior to permitting a horizontal drilling well. The model RUMA received support from both the oil and gas industry and local governments and can be found at www.ceao.org.

The model RUMA requires:

- A defined route, from State Route to pad;

- Bonding unless the road can be shown to withstand the expected truck traffic, the driller agrees to pay to improve the route, or a bond/surety is already in place;

- Maintenance of the route during drilling activity;

- Notification to the railroad industry if a crossing is involved;

- Videotaping of the route prior to drilling activities; and,

- Any additional provision the County and/or Township mandates.

In Perry Township, for instance, transportation officials were preparing to resurface a road. They determined that the large, heavy trucks driving on it would make resurfacing wasteful because it would only last three years. Chesapeake Energy partnered with the township and contributed $1 million to the project. They did more work on that road than they would have otherwise – widening the road, using different materials with greater thickness and different drainage – but now expects eight to 10 years out of the road.

Water use and wastewater

The hydraulic fracturing process releases gas trapped in rock pores by forcing fluids down gas wells at high pressures that will crack the rock and allow gas to escape into the well and rise to surface for collection.[75] A large portion of the chemical-laced fluids used for shale drilling remains trapped below the surface (20 to 40 percent).[76] Most of the used shale drilling fluid is collected at the surface after drilling and put into lined impoundments or storage tanks for future disposal. From there it can be treated by a mobile water recycling station for reuse, piped to a water recycling facility, trucked to a water injection well or deposited in landfills. While drilling fluid is made up largely of water, roughly 10 percent of the fluid is sand and chemicals, some of which are toxic.

Each well requires use of an estimated six million gallons of water. Only 6.5 percent of the water used in the fracking process is recycled for reuse. In dry years, the high demand for water in fracking operations could compete with water needs of the residential and commercial sectors, squeeze out local agriculture and/or raise water prices.

Residents express concerns that fracking fluid may contaminate drinking water. Carroll Concerned Citizens, a citizen-based organization formed to educate residents about the long-term health, economic and environmental impacts of mineral extraction activities, have raised concerns that fracking fluids used in drilling could eventually contaminate drinking water supplies. Since 95 percent of Carroll County residents draw from well water, not city water, the potential for groundwater contamination from fracking wastewater is disconcerting to local residents. Of particular concern to Carroll Concerned Citizens is the lease to the oil and gas industry of the non-surface mineral rights to a water field from which local drinking water is drawn. Drilling here will take place near a large drinking water supply. As of the summer of 2013, there were no wastewater violations in Carroll County, according to local environmental and health officials, and few official complaints. However, in nearby Youngstown, a man was indicted by a federal grand jury for dumping 20,000 thousand gallons of fracking waste into the Mahoning River.[77] Local residents interviewed said that they feel that it’s up to them to monitor the situation and ensure that their drinking water is not contaminated. As a result, Carroll Concerned Citizens started doing water quality testing and training others to do it; 45 residents are now trained. The group is working with the University of Cincinnati to monitor water quality over the long run.

Fluid disposal represents a cost to outside communities. Ohio allows fracking waste that is less than 20 percent liquid to be disposed of in landfills throughout the Ohio, creating the potential for leachate to end up downstream. Liquid waste typically is put back into injection wells that are often located in communities with no shale development. In 2012, 14.2 million barrels of shale drilling waste fluids were legally injected into Ohio’s nearly 200 disposal wells, according to data compiled by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources; this generated an estimated $43 million in related revenues for disposal well operators but has been tied to a number of earthquakes in the state.[78] More than half of that wastewater came from other states, including Pennsylvania and West Virginia.[79] The flow of shale waste into Ohio started in 2011 after businesses in Pennsylvania were ordered to stop dumping it into the state’s streams. Since Ohio has a less-restrictive licensing policy for injection wells than Pennsylvania, and more suitable topography than West Virginia, companies are shipping increasing levels of waste to Ohio.[80] High levels of wastewater brought in from other states may be straining local capacity and creating a need for greater use of alternative treatment options.[81]

Other health and environmental costs, nuisances

Flaring pollutes the air. In Weathersfield Township in Trumbull County, Ohio, Halcon Energy flared a gas well for two weeks near a neighborhood of 800 low-income families. The orange flame from flaring created a bright light all night, made an extremely loud noise at a decibel similar to a tornado warning, and emitted noxious fumes. Residents were concerned for their health and property values. Wildlife fled, and pets were afraid to go outside.[82] Flaring from shale development has been such a problem in North Dakota that one report estimates that one-third of all gas is burned in the air, creating $100 million a month in economic waste.[83] Energy is flared when there is insufficient infrastructure to process and transport all the gas extracted, since natural gas, unlike oil, cannot be stored indefinitely. A Pennsylvania study found nearly 30 cases of negative health impacts from exposure to drilling-related air or water pollution in people living close to wells or processing plants – including skin rashes, eye irritation, breathing problems, headaches, and dizziness.[84] Air pollution, including benzyne, toluene, and formaldehyde is a bigger threat in the short term than water pollution, according to the study. Extremely high levels of air pollution were found in homes within 1,000 feet of a processing plant. [85] Long-term exposure to these substances can affect the immune system and cause cancer, dizziness, confusion, and brain damage.

Fracking creates noise pollution. Well pads are often noisy and can run 24 hours a day, seven days a week. According to one interviewee, the loud noise at a secluded log cabin in Carroll County seriously detracts from the rural setting and disturbs its homeowner. Another property in the county with two well pads has a noisy pumping station the size of semi-truck. Interviewees said these stations can be enclosed and the noise significantly reduced, but Ohio law does not require it.

Shale development can affect the ecosystem and biodiversity. According to a database kept by the Ohio EPA, there were six slurry spills related to pipeline construction in the first quarter of 2013. These slurries were made up of clay and water, and did not contain dangerous pollutants, but the spills smother plant life in streams and wetlands causing “significant degradation.”[86] In another example, a proposed 250-mile natural gas pipeline that would deliver shale gas to Canada, routed through mostly farmland, restricts the growth of trees.[87] Changes in plant life can impact the habitat of other species.[88]

Expectations and future development

Industry activity has been steadily increasing but it has not been a tidal wave of development as initially anticipated. There is uncertainty about what to expect going forward, a lack of clarity that makes it difficult for local government officials and businesses to plan. Policy makers are in a difficult situation: they are being asked to invest resources in water, sewer, road and other infrastructure, and in training, and they are being told that insufficient investment might mean missed opportunities. But the resources needed are substantial and if the boom does not materialize, scarce money, time, and community hope will have been misallocated and the burden to cover costs left to residents.

With current gas prices so low, investors are looking at companies with acreage producing higher levels of oil versus dry gas.[89] Ohio shale wells have produced more gas than oil.[90] As a result, the flurry of activity in Ohio from 2009 to 2012, has slowed after a series of write-downs of shale assets from oversupply, dropping gas prices, and disappointment that wells have less oil than originally expected.[91] Permitting activity in Ohio nearly stopped in early August 2013.[92] Two companies have seen higher oil-yield operations in Harrison and Guernsey counties in Southeast Ohio; one announced it is expanding in the region.[93]

With respect to gas, Ohio’s lack of midstream processing facilities and appropriate pipelines has created a production bottleneck.[94] Midstream refers to pipelines, refineries and the like that take gas and liquids from the upstream well pad to downstream utility/distribution companies. Ohio’s existing pipeline infrastructure is not designed to handle Utica shale production, which requires different pipelines, gathering lines, processing and fractionation facilities. A new system of pipelines and processing plants is needed to take hydrocarbons from the well pad to the end-user. Energy companies now send recovered oil and gas to Canada or the Gulf Coast for processing.

Industry focused on addressing a midstream processing facility bottleneck in 2013. Major midstream projects have been announced or are under construction with potentially billions of dollars of capital investment going into Ohio. [95] According to Chesapeake Energy, processing constraints have curtailed production to date, with only 25 percent of their wells in production.

Limited access to centralized sewer and water infrastructure impedes development. Carroll County’s lack of the necessary infrastructure is one of the biggest barriers to housing and business development. The county’s Environmental Services department has gotten a number of infrastructure-related inquiries from oil companies, engineers, architectural firms and economic development officials. Companies need water and access to wastewater treatment plants. It is estimated that only 5 percent of land in the county has municipal water and centralized sewer infrastructure, all within the municipalities of Malvern and Carrollton. The remaining 95 percent of both commercial and residential properties rely on well water and self-installed septic systems. Many of these properties are in need of new and expensive septic systems (ranging in price from $11,000 to $30,000). There are huge swaths of land without any water and sewer infrastructure. The county is studying the possibility of infrastructure expansion, which would be very expensive. Companies and housing developers need and want access to the system, but expansion comes with risks. User fees would fund any expansion of centralized water and sewer systems. If the shale boom does not develop as anticipated, expansion cost will be borne by existing users. There has been interest from oil and gas companies to help pay. It is also possible that Carroll County will need another waste treatment center to accommodate increased development, adding another potential source of costs. Fortunately the county upgraded existing wastewater facilities a few years ago and added 33 percent in excess capacity that observers believe will be adequate at least for some time.

Carroll County seeks opportunity, while preserving its rural, agricultural identity. Is it possible for county residents to take advantage of the opportunity shale development presents without turning their backs on agriculture, scenic value, and tourism? Rural communities have an abundance of natural assets, including watershed resources and lakes. But they need economic opportunity too. Some think the top priority should be preserving the rural character of their community. Others are concerned that fracking development will prove devastating to the local ecosystem and dangerous to human health and biodiversity. Others feel that the potential jobs and economic activity justify the risks.

Local hire, employment services, education and training

Could oil and gas companies do more to hire locally? Some local residents accept that oil and gas industry jobs will not go to local workers, and are content with the opportunities created in supportive industries. They reason that industry offers hard jobs that few locals want anyway, given their intense 12-hour shifts. Several interviewees also repeated a rumor that only some of the local population would be eligible for drilling jobs because a high percentage would fail drug tests. Union halls, however, are not satisfied with this explanation. Union workers picketed locally, saying they have qualified local apprentices who could and would do the work.[96] In 2013, there was a pipeline-related protest made up of a mix of both union and non-union workers in Cambridge.[97]

The need for employment and training services has increased. The Ohio Department of Job and Family Services office in Carroll County has been concentrating on getting people jobs driving trucks and doing other support work in the industry, as well as low-level jobs on rigs. This office helps workers get the certifications, such as commercial driver’s licenses, that they need to get on a site. Ohio’s central workforce development office emphasizes short-term and on-the-job training to reduce costs. When possible, the agency directs people to fields that have short training programs, rather than fields that require two-year degrees. ODJFS reimburses employers for half the employee wages during training and helps residents with soft skills, resume writing, GED prep, and securing food and cash assistance while studying or in training. According to Census data, only 84 percent of the county’s population has a high school diploma or its equivalent, which means a relatively large number of residents may have trouble finding jobs. Recent cuts in Workforce Investment Act (WIA) funds, combined with increased demand for employment and training services, have made it more difficult for the local agency to meet needs, despite consolidation and cost-cutting.

Local schools and colleges are gearing up. The goal of ramping up training is to increase local hiring for higher-paying oil- and gas-industry jobs. A few educational institutions and vocational schools are developing or expanding existing training programs to ensure workers have needed certifications. The superintendent of Carrollton Village School District has been talking to partners about building an Energy Resource Academy for high school students, modeled on a program in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. He envisions the center having dual tracks – one academic, such as pre-engineering, the other for those who don’t plan on college, such as fire safety. The New Castle School of Trades in Pennsylvania recently doubled the size of its campus about 20 miles east of Youngstown to accommodate growth spurred in part by shale development. It now includes training in truck driving, heavy-equipment operating, welding, construction and electrical work.[98] Stark State College, an Ohio community college roughly 35 miles from Carroll County, was recently awarded over $3 million from the Department of Labor and the Timken Foundation to develop an associate degree and certification programs based on a curriculum tailored to the industry. In partnership with Stark State, America’s Natural Gas Alliance established a $1,300 scholarship covering cost of books, tuition and training for up to 40 veterans.[99] Buckeye Joint Vocational School, Kent State University, and Youngstown State University are adding programming related to shale work.

Government revenues and jurisdictional issues

Shale industry development has increased local government revenues, but officials do not yet know where the budget will stabilize. Prior to shale development, revenues were contracting. Employees experienced a five-year wage freeze, and the county government started losing employees to better-paid industry jobs. Increased economic activity is now generating more sales tax revenue, which increased in the county to $2.55 million in 2012 from $1.67 million in 2009.[100] More income is being generated in the courthouse where the county recorder is processing more deeds, mortgages, and leases. Oil and gas industry drivers, especially of heavy trucks, buy a lot of fuel and pay the fuel tax, which helps cover some of the increase in road costs.

Last year, for the first time, Carroll County saw a revenue surplus. The surplus enabled the county to give employees a 3 percent salary increase. Much of the rest of the increase in tax resources went toward the local sheriff and to train and add to dispatch services. The county added staff at the recorder’s office, which had seen long lines for a time. The crush of activity has subsided, but increased activity is seen as the office’s new normal. Now, a year later, the mapping office is overrun as industry looks to add pipeline capacity and processing plants, but the county has yet to increase staff there. The sheriff would like to add a person to handle increased traffic issues. If the county expands sewer and water infrastructure, additional staff will be needed. Separate deeds for oil and gas rights, sometimes filed by limited liability companies, involve separate bookkeeping and new parcel numbers allotted for mineral rights, which generates increased tax revenues. Signing bonus payments to local government are also a source of one-time funds. Local officials believe these funds are best used on capital projects or to pay off debt since they are one-time funds. When they receive royalties, they believe these can go to the general revenue fund since they will be ongoing.

Ad valorem tax revenues go to school district. A recent article on the Springsboro school district in Warren County in Southwest Ohio cited an expected increase of $7 million per year in school revenues due to increased property values from a new pipeline built to pump natural gas to Texas for shipping overseas.[101] Pipelines increase property values, and in turn property taxes, and 70 percent of the property taxes paid by pipeline companies go to area schools. The additional revenue could last for decades. The increased funds will help stabilize finances and staffing and meet rising medical insurance costs, despite cuts in state school funding.

State and local jurisdictional issues. In the past, oil and gas drilling was largely regulated locally. In 2004, Ohio House Bill 278 preempted local governments’ home rule power to regulate drilling. Ohio law states that while oil and gas companies may appeal the denial of a permit to drill, citizens cannot appeal a permit that is granted. A court case is pending before the Ohio Supreme Court challenging pre-emption under constitutionally granted home-rule power. As of now, also as a result of the law, if the local health and environmental services department investigates a complaint that turns out to be drilling related, such as something related to toxic waste, it goes to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources or the Ohio EPA. No well-water testing is done locally either.

Recommendations

Increase Ohio’s severance tax to 5 percent and use it to maximize benefits, minimize costs. The severance tax – collected by the state and distributed back in measure to impacted counties – has long been considered an appropriate source of funds to address the external costs of natural resource extraction. Ohio’s current severance tax is formulated for a small oil and gas industry. However, horizontal shale drilling is boosting the oil and gas industry into a new phase. There are serious needs developing in drilling-impacted communities and the severance tax is the way to cover such costs. Ohio and Pennsylvania should join West Virginia in levying a 5 percent severance tax on oil and gas. The tax should be used first for industry oversight and regulation and for covering the costs borne by communities where drilling is done, wastewater stored, and anywhere the impacts are felt: in the roads leading to the wells, the streams flowing through the drilling areas, the RV parks where the transient workforce stays.

The 5 percent severance tax could help:

- Tackle transportation issues. Investments in rail could help relieve pressure on local roads, reduce congestion, accidents and fatalities.

- Support local and state government increased staffing and service needs. Hiring dispatch and EMS workers should be a priority, as should be digitizing records in the recorder’s office as well as those needed for other purposes, such as mapping to produce projections and planning support for smart development purposes. Other priorities include employment, education and workforce development services and infrastructure.

- Address housing issues. Increased funds could enable local jobs and family service agencies to increase housing stipends for low-income workers and enable them to better handle rising rents by matching PRC funds to the increase in rent prices).[102] The state should consider using funds to offer competitive funding for rehabbing existing properties and the development of affordable housing for seniors, and to provide support for the creation of local redevelopment agencies to get the work done.

- Creation of a local oil and gas taskforce to coordinate discussions between agencies and communities, stakeholders and companies. This would help county residents identify issues, flesh out best practices, consider solutions, and open dialogue within the community. State severance tax funds can be used to support these task forces.

- Protect landowner and citizen rights. Communities may want to help form landowner associations early in the development process. The state should provide support for landowner associations and legal services related to leases and environmental issues and do serious, independent monitoring of water quality and other environmental health issues. Alternatives to flaring, such as well sites using green completion equipment, should be required. Best practices from coal mining reclamation to address deforestation should be employed. Drillers should be required to submit a pollution control plan.

- Come up with ways to encourage the oil and gas industry to hire more local workers and provide health insurance. Fracking jobs are too dangerous for workers not to have health insurance. Failure to provide adequate insurance could mean short- and long-term costs to the community in the form of uncompensated care at local hospitals.

- Boost public health resources. New funding is needed in public health to enable monitoring of air quality, noise levels, and water quality, to oversee all trailer parks, RV sites and temporary housing facilities of the transient workforce, and to track changes in emergency room visits and all other health indicators throughout regions impacted by the oil and gas industry, its infrastructure and its workforce. Health concerns are of primary importance on their own, but can also affect property values if areas where fracking occurs are seen as less desirable places to live and work. Western states have seen property values fall in oil and gas communities, in part because of infrastructure destruction and in part because of concerns about the impact of fracking on health. Mortgage lending in Pennsylvania has been affected.

An additional 2.5 percent tax should be set aside in Ohio’s Advanced Energy Fund. This would allow investments in infrastructure designed to use energy locally and diversify our energy portfolio. In 2011, Ohio spent $51 billion consuming energy – including $30.2 billion on petroleum to fuel our cars and trucks, $13.9 billion on electricity to power our homes and businesses, and $6.1 billion on natural gas largely for heating purposes. The $51 billion spent on energy is roughly 10 percent of the state’s $484 billion gross domestic product.[103] Only 28 percent of that energy is currently produced in Ohio.[104] We purchase the rest from out of state or out of the country, a huge drain on Ohio’s economy.[105] Shale oil and gas development can help to increase the amount of energy Ohio produces relative to the level we consume. In 2011, however, Ohio consumed 10 times the amount of natural gas we produced. In 2012, Ohio produced six times more shale gas than it did in 2011, which helps, but this level of natural gas production still only amounts to 12 percent of the natural gas we consumed, and is less energy than Ohio got from renewable energy sources.[106]

Unless Ohio sees a more significant increase in natural gas production, and uses it locally, it won’t make a substantial difference in the level of energy Ohio imports from out of state. Current commitments to building more natural gas infrastructure are expected to result in a large increase in Ohio shale gas production. Much of the infrastructure being proposed, however, will focus on exporting gas out of Ohio. One proposed 500-mile pipeline, for instance, would connect Ohio to Louisiana in order to reach foreign markets.[107] If the bulk of Ohio’s shale gas is shipped to foreign markets, then Ohio’s natural gas prices will likely rise to meet global energy prices.[108]

There are some efforts underway to capture the value of having homegrown energy for Ohio consumers. An $800 million gas-fired power plant proposed in Carroll County, for instance, would produce enough electricity for 700,000 homes while also creating 500 construction jobs and roughly 25 permanent jobs operating the facility.[109] The chairman of the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio has welcomed this kind of shift from coal-fired generation to natural gas, and the Ohio Power Siting Board recently approved an even larger gas-fired plant in Oregon, Ohio.[110]

A shift from coal to natural gas power plants will make the production of electricity more efficient, reduce prices to consumers, and reduce emissions. More of this sort of investment should be encouraged through a permanent fund to upgrade Ohio’s energy infrastructure. Some of those funds should be used to invest in renewable energy sources. Natural gas production in Ohio, even if it all stayed local, is not likely to sufficient to meet all of our energy needs. In order to meet our energy needs sustainably we should set aside funds for investments in energy efficiency and solar as well as other alternative energy sources that will help diversify our energy portfolio.

Provide risk insurance for environmental and health impacts and remediation. Companies should bear the risk of loss from environmental mishaps and consequential damages to resident health. Insurance companies are best able to determine that risk. The state should purchase, or require oil and gas companies to purchase, insurance for these purposes. If the risk is low, as the industry says it is, then the cost to insure that risk should be minimal.

Conclusion