Cutting Ohio Top Income-Tax Rates Would Be Costly, Favor a Few

Posted January 03, 2005 in Press Releases

A move to cut state income-tax rates on the most affluent would cost Ohio hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue and tilt the state and local tax system further against lower- and middle-income taxpayers. Those are the key conclusions of a review released on January 3, 2005 by Policy Matters Ohio, based on calculations made by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), a research group in Washington, D.C., with a sophisticated model of the national and state tax systems.

Currently, Ohio’s personal income tax has nine brackets. Income over $200,000 a year is taxed at a rate of 7.5 percent, and income between $100,001 and $200,000 is taxed at 6.9 percent.

Eliminating the top bracket would cost the state $114 million a year, or at least twice that during the biennial budget beginning July 1, 2005. The top one percent of Ohio taxpayers – with average income of $619,900 a year – would receive 97 percent of the tax cut. Taxpayers in this group, who each make at least $263,000 a year, would pay an average of $2,038 less a year in state income taxes. While a total of fewer than 90,000 taxpayers would receive such cuts, 5 million Ohio taxpayers – the bottom 95 percent by income – would receive no benefit from this change.

If the state eliminated both of the top brackets, so that the top rate was 5.943 percent, it would lose $434 million each year. To put this in perspective, this is nearly equal to the amount distributed by the state through the Library and Local Government Support Fund, the main source of revenue for most libraries in Ohio. It is more than double the state’s General Revenue Fund spending last fiscal year on the Department of Youth Services, or more than a sixth of such state spending to support higher education.

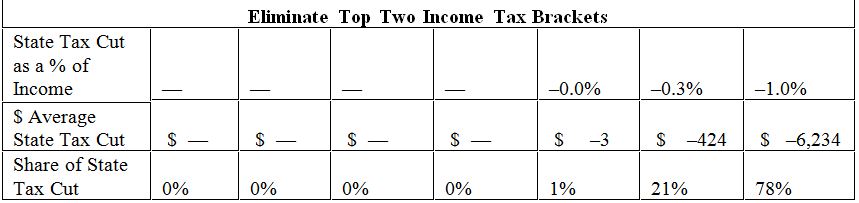

If the top two brackets were eliminated, more than 99 percent of the benefit would go to the top 5 percent of Ohio taxpayers. Almost four-fifths of the reduction would go to the top one percent, who would save an average of $6,234 a year. Nearly all of the rest would go to those in the next highest 4 percent, who make between $115,000 and $263,000. In short, the benefits of such a cut would be highly concentrated among the very richest Ohioans. The table below illustrates how eliminating the top brackets would affect various income groups in Ohio.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, December 2004

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, December 2004

Many wealthy Ohio taxpayers would lose up to a third of these benefits due to increased federal income tax obligations, as they would have less in state income tax to deduct on their federal returns. Overall, eliminating the top two brackets would reduce their gains by 20 percent, or $89 million. Thus, this would be a dubious economic development proposal, since the net effect would be to funnel these funds out of Ohio.

An ITEP study in June 2004 found that between 2001 and 2004, the top one percent of Ohio taxpayers would receive federal income-tax cuts amounting to $90,000 apiece, on average. This far outweighs the $6,234 the wealthiest one percent would receive on average from chopping the top two state income-tax brackets. However, during the time period, Ohio has lost more than 240,000 jobs. It seems highly unlikely, if major tax cuts for this income group have not delivered economic growth, that much smaller ones are likely to have a significant impact on jobs and income.

There is little evidence to support claims that Ohio income-tax rates are hampering economic growth. States such as North Carolina and California, with among the highest top income-tax rates in the nation, developed high-technology centers that we envy. A recent survey of the economic literature by Robert G. Lynch, chairman of the economics department at Washington College, found little grounds to support tax cuts – especially when they come at the expense of public investment – as the best means to expand employment and spur growth.

Current Ohio law already reduces income-tax rates for all taxpayers when the state is running a budget surplus. Under these reductions, rates were reduced between 1996 and 2000 by a total of more than $2 billion.

Ohio’s graduated income tax is a crucial element in keeping overall state and local taxes from being overwhelmingly tilted against middle class and low-income taxpayers. Other taxes require that Ohio’s less affluent citizens pay more as a share of their incomes than richer taxpayers do. As a result, high-income taxpayers pay a smaller share of their earnings in state and local taxes than Ohioans who make less. The income tax is the main tax that to a degree offsets this, and requires that more affluent people pay more, as they can afford to do.

The bottom 60 percent of Ohio’s workers have seen little or no increase in real hourly pay over the past 25 years. By contrast, the top 10 percent saw 19 percent growth between 1979 and 2003. Cutting out Ohio’s top brackets would increase this growing inequality.

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy is a nonprofit, nonpartisan Washington–based research group. Its tax model is similar in methodology and data sources to the elaborate computer models used by the U.S. Treasury and the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation, except that the ITEP model adds state-by-state estimating capabilities. The figures show the effects of 2003 state and local tax laws, at 2003 income levels.

For a later report, see Wealthiest Ohioans Gain Most From Proposed Tax Changes; Low- and Middle-Income Families, on Average, Save Little or Nothing

February 2005 release, analyzing the proposed 22% reduction in Ohio's State Income Tax:

State Income-Tax Cut Would be Expensive, Unequal and Would Siphon Money Out of Ohio