State of Working Ohio 2014

August 31, 2014

State of Working Ohio 2014

August 31, 2014

Download summary (2pp) Download report (25pp)Press releaseLabor Day report issues urgent call for job creation as job growth stagnates, workforce participation falls to an all-time low since tracking began, and median wages fall just as worker productivity exceeds that of a generation ago by two thirds.

Executive summary

Executive summary

The State of Working Ohio 2014 finds that Ohio workers have gotten more educated and more productive, but they’ve fallen behind in wages and income over the long term. More troubling, Ohioans continue to leave the labor market in record numbers more than five years into an official recovery.

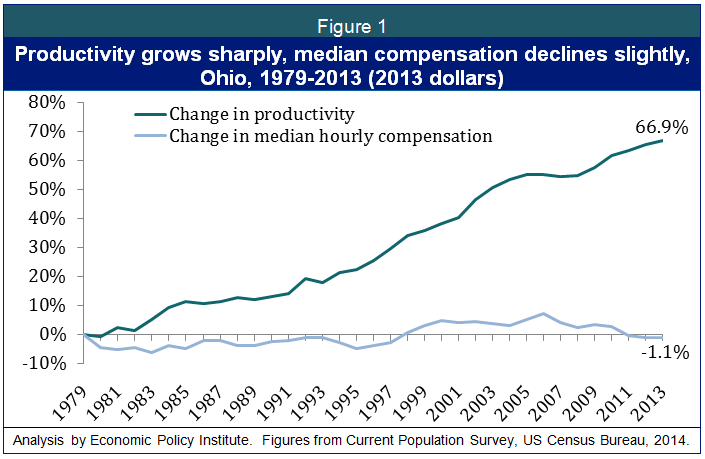

Productivity: Ohio productivity grew by 66.9 percent while compensation of the median worker fell by 1.1 percent in inflation-adjusted terms between 1979 and 2013.

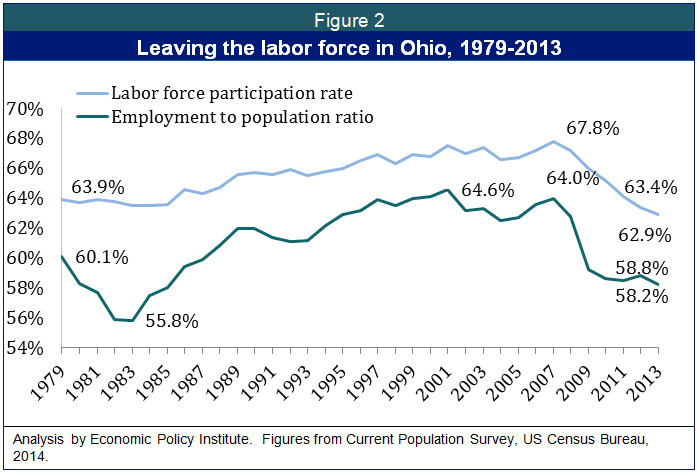

Labor Force Participation: In 2013, labor force participation fell to its lowest level since 1979 when we began tracking it. By last year just 62.9 percent of Ohio adults were in the labor force, down from 63.4 percent in 2013 and down from a peak level of 67.8 percent in 2007. Men had their lowest labor force participation since we’ve been tracking it last year and women’s labor force participation, which had risen throughout the 1980s and ‘90s, is well below its peak in 2007. Only 48.3 percent of African Americans were employed as a share of the black population in 2013, lower than at any point since the early 1980s.

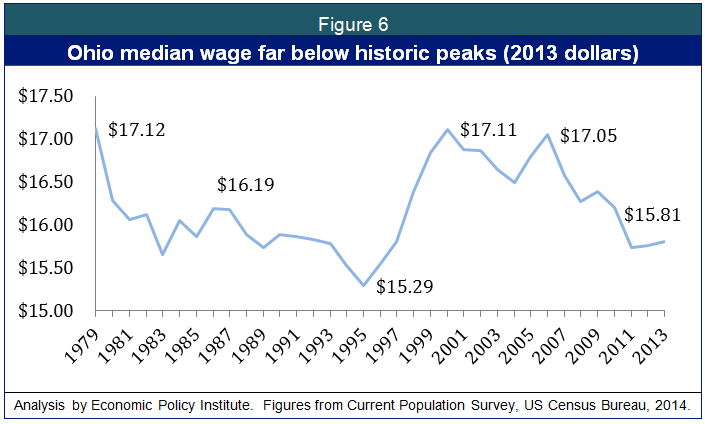

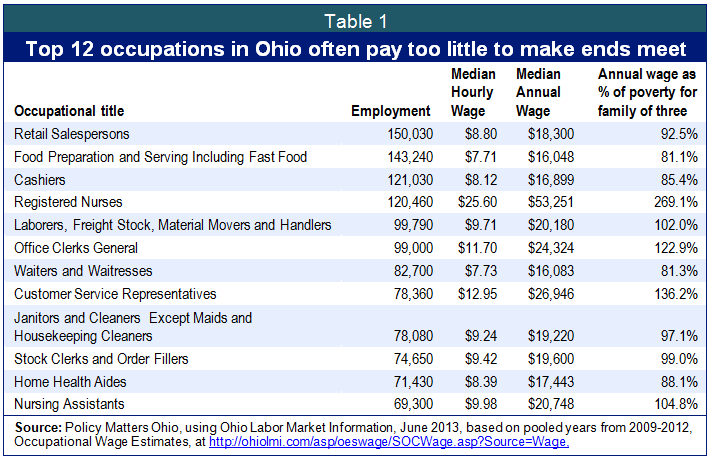

Wages: Ohio’s median wage was just $15.81 in 2013, a hair above 2012 but well below the highs of $17.11 and $17.12 experienced in 1999 and 1979. Ohio’s median wage is now nearly 90 cents less per hour than that of the median worker nationally. Gaps between the wages of men and women or black and white workers remain troubling. In almost all of Ohio’s largest occupational categories, wages are too low to bring workers above 150 percent of the official poverty level (widely recognized as paltry) with full-time work.

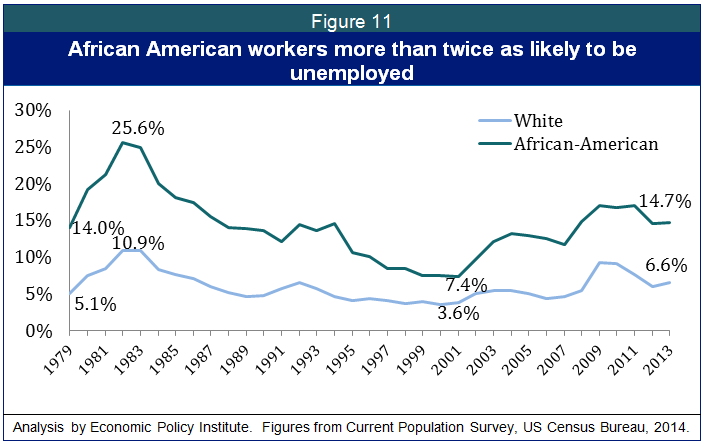

Unemployment: The annual unemployment rate in 2013 remained high, though lower than in peak years, and black workers were twice as likely to be unemployed as whites. The unemployment rate has improved substantially in 2014, but some of that is due to workers leaving the labor market.

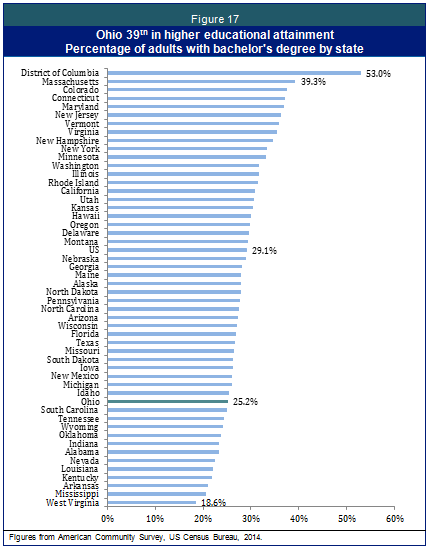

Education: Ohio workers have gotten more educated, but our education levels lag behind those of many other states – we rank 39th in BA attainment, with 25.2 percent of our population at that level, well below states like Massachusetts where 39.3 percent of workers have a BA. Still, the share of the workforce that has a BA has nearly doubled, from 14.7 percent to 28 percent since 1979 and the share with some college is now well over half the adult population, up from just a third of the population in 1979. More educated workers as a group have much higher wages and lower unemployment than less educated workers. However, of workers making $10 or less an hour in a recent three-year period (2009-2011), fully 43 percent had some college or a bachelor’s degree, while between 1979 and 1981 under a quarter had that level of education. Clearly Ohioans’ attempts to become more educated have not always paid off in higher wages.

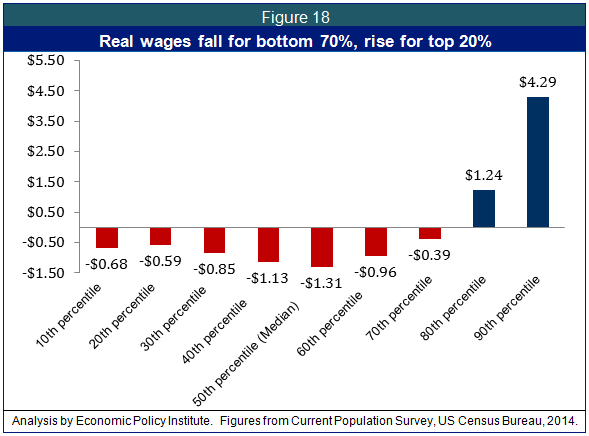

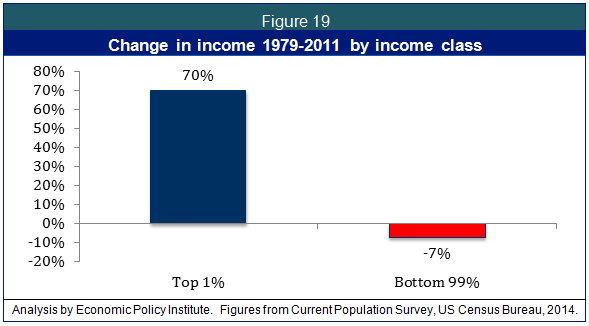

Inequality: Wages and incomes have become far more unequal in Ohio in the past generation. If we divide the workforce into ten equal parts, the bottom 70 percent of workers have seen their wages decline in inflation-adjusted dollars compared to similar workers from 1979. Inequality within the top ten percent is even greater. In data that is new this year, we examined Ohio income changes between 1979 and 2011 among the top one percent and the bottom 99 percent. When grouped this way, in Ohio, the bottom 99 percent as a whole actually saw its income decline by 7 percent, while the top one percent experienced a 70 percent income growth.

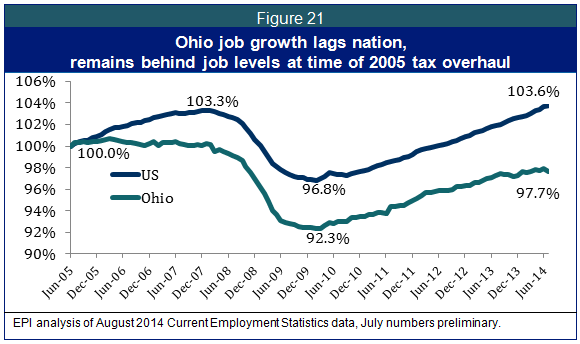

Job Creation: Neither Ohio nor the U.S. are creating enough jobs but the state story is worse. In 2005, Ohio policymakers slashed taxes for the highest income and businesses, claiming it would generate jobs. Since the 2005 tax cuts, Ohio has lost 2.3 percent of its jobs while the nation has added 3.8 percent. This is partly because Ohio slashed public jobs since the start of the recent recession, further weakening a bad situation. We’ve cut more than 7 percent of our local government jobs since the start of the most recent recession and nearly 8 percent since the 2005 tax cuts.

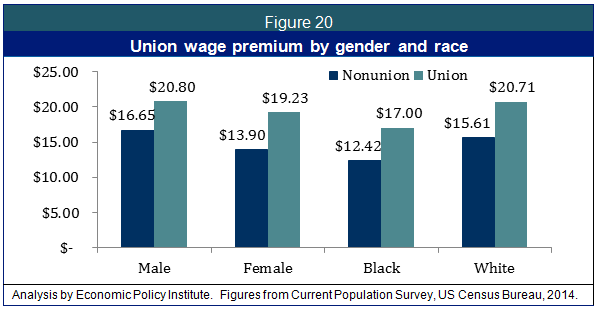

Fixes: Unions and education are two institutions that can help raise wages. Workers who are in a union or who have more education generally earn significantly more than those who are not in a union or have less education.

Recommendations: The report finds that the biggest problem in Ohio, also true to a lesser extent nationwide, is a lack of labor demand. We recommend several policies to increase employment that would also improve our communities and make Ohio more vibrant and efficient in the future. These include rehiring laid-off public sector workers, expanding access to education from pre-K through college, and investing in building efficiency, renewable energy and transit, in part by restoring Ohio’s clean energy standards. These smart investments will reduce future costs for remedial education, incarceration, unemployment and energy while increasing employment now.

Introduction

On Labor Day 2014, Ohio workers have little to celebrate. Some indicators have improved slightly since their most dismal levels, particularly the unemployment rate. But for the most part, working people are not sharing in our economic growth. Ohio’s economy is growing more slowly than the nation’s, but it is nonetheless highly productive with great rewards to some. Yet for the typical worker, jobs remain too scarce, wages remain too low and security remains elusive. It need not be this way. A different set of public policies and expectations is needed to ensure that the typical, median, middle-income people who contribute to our productivity also share in its growth.

The income decline and stagnation in Ohio could lead to an assumption that we are simply not growing. Nothing could be further from the truth. Inflation-adjusted productivity in Ohio has grown by 66.9 percent since 1979, meaning that workers are producing more than 1.6 times as much per hour. However, hourly compensation for the median worker has actually fallen over that time period in inflation-adjusted terms. Real wages were below 1979 levels in 21 of the 34 years since then, including 2013, as Figure 1 shows.

At the national level, productivity growth over a slightly longer period has been even higher – 80.4 percent between 1973 and 2011. But national inflation-adjusted median hourly compensation has grown just 10.7 percent over that period.

Dismal employment participation

Ohio workers continued to flee the workforce at alarming rates in 2014. The labor force participation rate is the share of adults that is either working or unemployed and actively seeking work. In 2013, this rate fell to its lowest level since 1979 when we began tracking it. By last year just 62.9 percent of Ohio adults were in the labor force, down from 63.4 percent in 2013 and down from a peak level of 67.8 percent in 2007.

The employment-to-population ratio reflects the percentage of adults who are actually employed. This indicator also fell last year, to 58.2 percent, from 58.8 percent the year before. Employment as a share of the population in Ohio is now at its lowest level since the mid 1980s. Figure 2 shows the change in labor force participation and employment-to-population share.

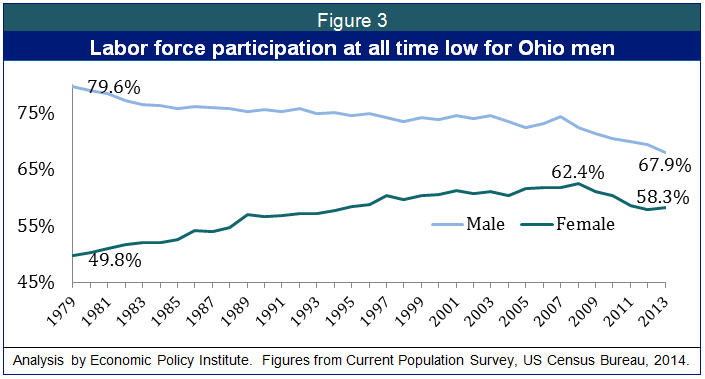

Male labor force participation fell steadily overall since 1979 with just occasional exceptions, while women’s grew almost every year between 1979 and the mid-2000s. Men’s participation revived slightly in 2006 and 2007 before dropping off sharply to an all-time low of 67.9 percent in 2013, a more than 12 percentage-point drop from the 79.6 percent rate in 1979. Women experienced a still larger decrease following the recession, with a slight revival this past year to 58.3 percent, down from a high of 62.4 percent, as Figure 3 shows.

The employment situation is challenging for all workers, but African-American workers in Ohio face a particularly difficult jobs situation. Only 48.3 percent of African Americans are employed as a share of the population, an indicator that declined last year and that is now as low as it has been at any point since the early 1980s. This is more than 11 percentage points worse than the employment-to-population ratio of white workers, which is itself in worse shape than it has been in the past thirty years as Figure 4 shows.

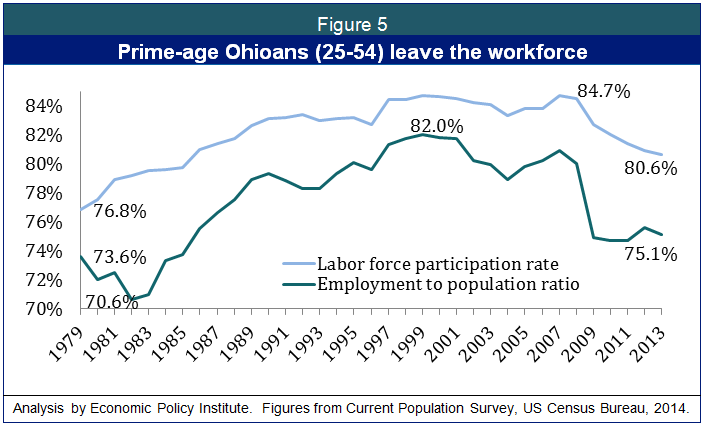

One argument that has been advanced about Ohio’s falling labor force participation is that Ohioans are simply older than people in other states and are therefore retiring. It is true that Ohio has fewer young workers and more older citizens than many other states. However, prime-age Ohioans, those between the ages of 25 and 54 are also leaving the labor force in Ohio, demonstrating that this is more of what economists call a demand-side issue. That is, there is insufficient demand for workers, forcing even those of prime working ages out of the labor force. Only 80.6 percent of prime-age Ohioans are now in the labor force (which includes both workers and those seeking work), lower than at any point since the late 1980s. Just 75.1 percent of prime-age Ohioans are employed, which is about on par with the last few years but otherwise lower than it has been since the mid 1980s. It is worth noting that in the 1970s, when these indicators were worse, fewer women were in the labor force.

Wages stay low

Ohio’s inflation-adjusted median wage rose slightly in 2013 to $15.81 per hour, a nickel above the $15.76 rate in 2012 and still well below recent peaks in 2000 and 2006 when the median wage was above $17.00 an hour in today’s dollars. Median wages remain lower than they were 34 years ago in 1979 and lower than in the majority of intervening years, despite strong growth in worker productivity since that time. Figure 6 traces median Ohio earnings from 1979 to 2013.

Ohio’s median wage is now nearly 90 cents less per hour than that of the median worker nationally. This is in contrast to the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, when Ohio’s median wage was far above, slightly above, or about equal to that of the median American worker. The typical worker nationally now earns $16.69 per hour, compared to $15.81 in Ohio, as Figure 7 shows.

Women continue to earn substantially less per hour than men in Ohio at the median, $14.63 compared to $17.25. This makes typical male worker wages more than 18 percent higher than women’s wages at the median. This gap has narrowed substantially since we first began tracking it in 1979, due to both declines in inflation-adjusted male wages and to smaller increases in women’s wages. Since 1979, men’s real wages have fallen by 17.1 percent, while women’s wages have grown by 16.1 percent. In recent years, male wages continued to fall while women’s wages stagnated. Women’s wages now lag 2001 levels by half a percent, while men’s wages have fallen 13.5 percent since 1999 and are lower, in inflation-adjusted terms, than in any year since we began tracking this in 1979, as Figure 8 shows. It is worth noting that despite the growth in women’s wages, the combined wages of a man and a woman at the median, $31.88, is lower in inflation-adjusted dollars than the combined wages of their counterparts in 1979, $33.41, so a family with both a man and a woman working at the median would have lost ground over this period.

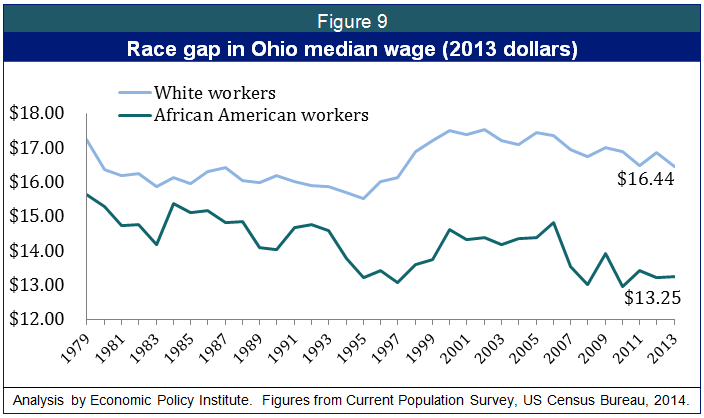

The racial wage gap widened substantially since the early 1990s in Ohio, with the median African-American worker earning just $13.25 in 2013, compared to $16.44 for the median white worker. Both white and black median worker wages are lower, in inflation-adjusted terms, than they were in 1979, but white Ohio workers earned 24 percent more than black workers at the median in 2013, as Figure 9 shows.

Of the 12 largest occupational categories in Ohio, just one (registered nurse) pays a wage that allows a family of three to be firmly above the federally-defined poverty line, which is widely recognized as extremely low. Table 1 illustrates that a worker in almost any of Ohio’s largest occupational categories earns median wages for full-time work that would not bring a family of three to even 1.5 times the very low official poverty level. More than half of these occupations actually pay below the poverty level.

Out of work

Many have left the labor force in Ohio and are not included in unemployment numbers, as the first section described. Nonetheless, annual unemployment in Ohio remained high in 2013 at 7.6 percent, slightly higher than the 2012 rate of 7.2 percent. This is down from the recent peak level of 10.3 percent in 2009 and from the highs in the early 1980s. It is significantly above unemployment rates seen in an economy with sufficient jobs, however. For example, throughout the late 1990s, annual employment was consistently at or well below 5 percent, even hitting the 4.0 percent level in 2000. Figure 10 shows the trend for annual unemployment. Note that unemployment figures are provided monthly and this trend has generally improved over the course of 2014 and was at 5.7 percent for the month of July, a substantial improvement.

African American workers are more than twice as likely to be jobless despite seeking work as are white workers. In 2013, nearly 15 percent of black workers were officially unemployed compared to 6.6 percent of white workers, as Figure 11 shows.

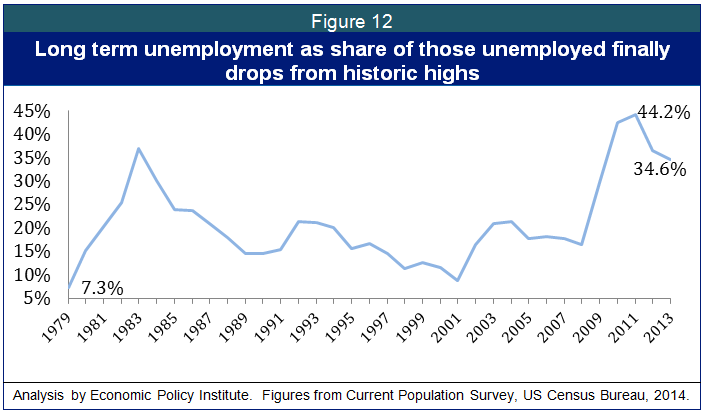

One disturbing element of recent economic reality is the high share of the jobless who have been out of work for more than six months. More than one in three unemployed workers is in this position, higher than at almost any point since the late 1970s, but lower than the past several years and down from a peak level of 44.2 percent in 2011. For one year in the early 1980s (1983), long-term unemployment constituted a higher share of the unemployed (36.9%), but never since we’ve begun tracking has it been so elevated for so many years in a row, as Figure 12 shows.

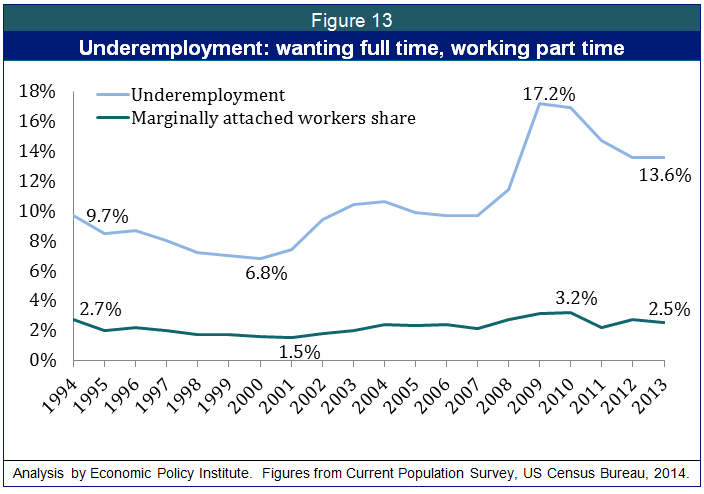

We also monitor what the federal government calls underemployment. In a weak labor market many workers accept part-time jobs when they’d rather work full-time, stop looking because they don’t think they’ll find a job, or stop looking because they lack the child care or transportation that they would need to be able to work. Beginning in 1994, the federal government began adding these variables together in a measure it calls underemployment, shown in Figure 13. The marginally attached line shows the workers who have stopped looking for work but do want work and are available for it. In 2013, 13.6 percent of Ohioans were underemployed, down from a peak of 17.2 percent in 2009 but far above the rates in the 1990s and early 2000s. In 2013, 2.5 percent of Ohioans were marginally attached.

Education pays, but it’s complicated

Annual unemployment is of course much higher for those with less education – nearly one in five workers without a high school degree was jobless despite seeking work in 2013, and nearly 9 percent of those with just a high school degree were also officially unemployed that year. For those with BA degrees, the rate was much lower, under 4 percent, as Figure 14 shows.

Workers have gotten more educated in Ohio over the past generation, with the share of the adult workforce that did not complete high school plunging from 24.4 percent to a still-too-high 8.2 percent. Well over half the adult workforce (56.9 percent) now has some college completed, up from 33.6 percent in 1979. A full 28 percent have completed a BA, up from just 14.7 percent in 1979 as Figure 15 shows.

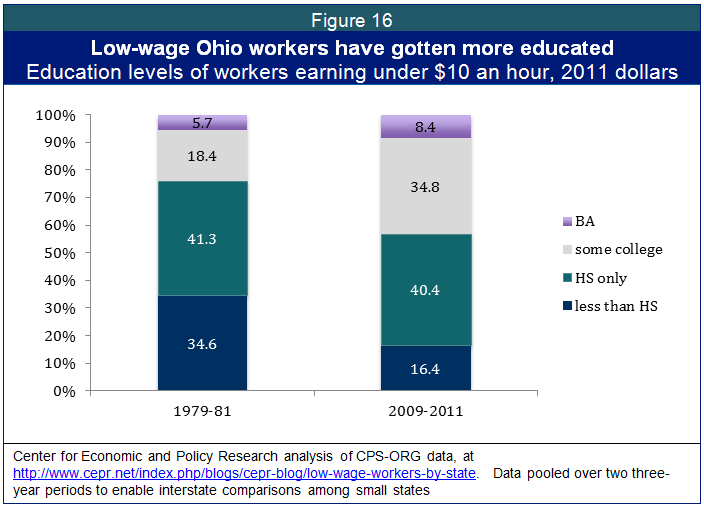

For any individual worker, getting more education means the worker is more likely to have a job and more likely to make better wages. But low-wage workers today are much more educated than they were a generation ago. Figure 16 compares a three-year period at the start of our analysis (1979-1981) to one toward the end of our analysis (2009-2011). We find that workers who made $10 an hour in 2011 dollars were much more educated in the later period. In the 1979-81 period, more than a third of these low-wage workers had less than a high school degree and under a quarter had some college or a BA. By contrast, in the later period, only 16.4 percent had less than a high school education, and 43.2 percent had some college or even a bachelor’s degree.

Although Ohioans have become much more educated, other states are investing more in the education levels of their people and experiencing better job or wage outcomes at least partly as a result.[1] Ohio ranks 39th in college degree attainment, behind 37 states and D.C. Degree holders comprise 25.2 percent of Ohio’s population age 25 and older. In the District of Columbia, an unusual case, 53.0 percent hold a BA or more. Massachusetts ranks next with 39.3 percent. The lowest ranked state is West Virginia, with 18.6 percent, as Figure 17 shows.

On the bright side, educational attainment is up for younger adult Ohioans. Among 25 to 34 year-olds, 38.0 percent hold college degrees. Ohio ranked in the middle in degree attainment for this cohort (26th out of the fifty states plus D.C.).

Growing apart

Wages have become much less equal in Ohio over the past generation. We divided the Ohio workforce into ten equal parts and took a snapshot of the wage level at the tenth percentile, twentieth percentile and upward to the ninetieth. The worker at the tenth percentile earns more than 10 percent of all workers and less than 90 percent. We found that for the bottom 70 percent of the earnings spectrum, inflation-adjusted wages are actually lower than they were for their counterparts on the earnings spectrum in 1979. That is, wages have gone down for seven out of ten Ohioans. The worker at the 90th percentile now earns $34.33 an hour, more than four times the hourly earnings of the worker at the tenth percentile, who now earns just $8.22 an hour.

Dividing the workforce into just ten parts only begins to capture the tremendous growth in income inequality in Ohio over the past generation because almost all of the growth in income has gone not just to the top 10 percent but to the top 1 percent. Inflation-adjusted incomes of the top 1 percent in Ohio grew 70 percent between 1979 and 2011, but the average real income for the rest combined actually fell 7.7 percent. In 2011, the average income of the top 1 percent in Ohio was 18.1 times as great as the average for the bottom 99 percent. Figure 19 captures the story.

The Union Premium

This report has demonstrated big problems with low wages and wage disparities based on race and gender. One factor that can make a difference in raising wages and reducing disparities is unions. For workers, whether black, white, male or female, unions raise wages and reduce disparities. Black workers who are in a union earn $17.00 an hour at the median, which is more than a third more than the $12.42 hourly wage that non-union African Americans earn at the median in Ohio. White workers also earn more when they are in a union, $20.62 compared to $15.61, also an increase of about a third. It is worth noting that, while the racial disparity endures, black workers who are in unions earn more than white workers who do not have a union contract.

Women also earn much more when they are in a union, $19.23 at the median, compared to $13.90 at the median without a union contract, again an increase of more than a third. Men, too, earn more in a union, $20.80 at the median in 2013 compared to $16.65 for non-union men, an increase of about 25 percent. Union women earned more at the median than non-union men in 2013.

The Answer: More Jobs

Neither Ohio nor the United States are creating sufficient numbers of jobs in what remains a weak recovery, though the state-level story is substantially worse. Ohio lags the country in job creation since 2005, when Ohio began phasing in major tax cuts justified on the notion that they would create jobs. Figure 21 brings our job numbers up to the most recent month and shows that our job growth has been consistently weaker than that of the country since those tax cuts. In the expansion of the late 2000s, the country added jobs while Ohio did not. In the recession of the early 2000s, both Ohio and the nation lost jobs, with Ohio’s loss being worse, as is often the case in manufacturing states. After the early 2000s recession, Ohio and the nation added jobs, although Ohio remained further behind its 2005 levels. Finally, in the last few months, U.S. job growth has been very modest, but steady, while Ohio has had a bumpier path, with good months often followed by bad months. By last month, Ohio had 97.7 percent of the jobs it had in 2005, while the U.S. stood at a slightly healthier 103.6 percent of its 2005 job levels, still far too low.

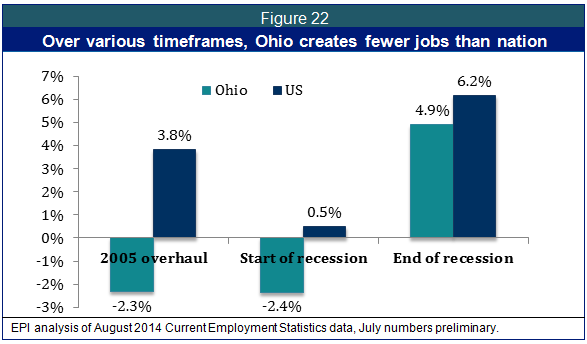

Figure 22 shows the same data in a slightly different way, illustrating how Ohio has lagged the nation in job growth in three different periods. Since the deep 2005 tax cuts, Ohio has lost 2.3 percent of its jobs while the nation has added to its job levels by 3.8 percent. Since the start of the recent recession, Ohio has lost 2.4 percent of its jobs while the U.S. has added .5 percent. And since the official end of the national recession, Ohio has added to its job levels by 4.9 percent, while the U.S. has added to its jobs by 6.2 percent.

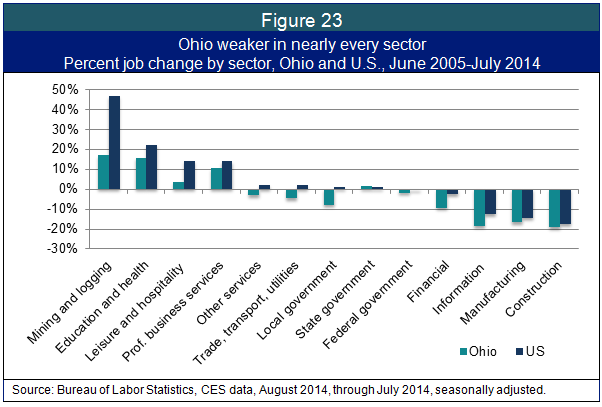

Ohio has underperformed the nation in percent job growth in every sector except state job growth between June 2005 and July 2014, as Figure 23 shows. In manufacturing, construction information, the financial sector, and the federal government, Ohio and the U.S. have lost jobs but the state lost more. In local government, trade, transportation and utilizes, and other services, Ohio lost jobs while the country has gained. And in mining and logging, education and health, leisure and hospitality, and professional business services, Ohio and the U.S. have added, but Ohio added a smaller share of jobs than the nation.

It is worth noting that the chart above makes certain sectors appear more important than they are to our local economy simply because they’ve added or lost a substantial share of their jobs since 2005. Figure 24 shows that manufacturing, trade, transportation and utilities, professional business services and education and health are the largest sectors in our economy. Mining constitutes only a tiny sliver of our economy.

There are things that Ohio and the nation can do to create jobs and we discuss some of these in the conclusion. But we can start with a sort of economic Hippocratic Oath: first do no harm. Ohio has slashed public jobs since the start of the recent recession, further weakening a poor employment situation. We’ve cut more than 7 percent of our local government jobs. We’ve added about 1 percent to our state level jobs when we use the comprehensive Current Employment Statistics numbers we generally use.[2] And federal cuts have also contributed. Combined, the federal, state and local actions add up to a five percent job reduction. Together, these public decisions have eliminated more than 40,000 public sector jobs in Ohio since the recession started, depriving our communities of teachers, firefighters and others, undercutting our recovery and removing spending from local economies. At a time when we had insufficient jobs, policymakers took the jobs over which we had most control and eliminated five out of one hundred of them.

Conclusion

A few indicators have gotten a bit better in the past year in Ohio, as they have nationally. But nearly all indicators are far worse than what we should expect this far into a recovery. Ohio remains, in most ways that matter to middle-wage workers, far behind its best days. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Looking at the Ohio data, we could make a case for actions to boost wages, like preserving or expanding union rights or raising the minimum wage. Those actions are needed. But in this conclusion, we focus on the source of the persistently high levels of joblessness, the record numbers of people leaving the labor market and the job growth that so badly trails that of the nation. All of these can be addressed with job creation strategies.

Here in Ohio, we’ve undercut our recovery by reducing public jobs. After the 1981 and 1990 recessions, Ohio added public jobs, providing a counter-cyclical boost to the economy, providing more of the services that families need when they are struggling financially, and getting projects done while it was cheaper to do them in a down economy. We should repeat that more successful approach now. Between the start of this recession and this month, Ohio policies have led to the elimination of 7.4 percent of our local government jobs, further weakening a poor employment situation. This meant not only that the displaced teachers, firefighters, social workers and bus drivers were unavailable to deliver valuable public services to Ohioans but also that they didn’t have money to spend, making our overall economy weaker and creating a downward spiral. They didn’t buy new school shoes, they didn’t go to the corner diner, they laid off the babysitter.

In addition to retaining and rehiring existing public workers, we have needs in our communities, which currently unemployed workers can fill, employing people now and positioning us better for tomorrow. Two clear areas for such investment are in people and in efficiency.

America created one of the world’s first K-12 education systems, and with the GI bill created the most educated workforce in the world, fueling our growth in the middle of the last century. But we are no longer making the new investments needed so that young Ohioans can be ready to thrive and excel in our new, more demanding economy. And other states, not to mention other countries, are passing us by.

Ohio can boost jobs by providing high quality early care for infants and toddlers, which positions children well for future success and helps parents stay employed. But Ohio has gone backwards. We have one of the lowest eligibility rates in the nation for state childcare aid: eligibility was reduced from 150 to 125 percent of poverty in the last budget. A parent earning $25,000 could not become eligible for childcare help, yet half her income would be consumed by childcare costs.

On pre-kindergarten education, there are some promising local initiatives, but Ohio is not keeping pace with countries and states that are putting in place universal high quality pre-kindergarten for all three and four year olds. We were once a leader, under Governor Voinovich, on state funded Head Start. But recently, Ohio ranked 37th for enrolling 4-year olds in state pre-K in 2012. Better early childhood investments would create demand for workers and reduce unemployment now, while permanently improving lives and reducing future costs.

In Ohio, state funding for K-12 education in this budget is more than $600 million dollars lower than it was in 2010-2011. When we surveyed districts about this last year, 70% said they were cutting their budgets, doing things like laying off teachers, getting rid of aides, raising class sizes, and eliminating course offerings.

Ohio has slashed aid for college students by a third over the past 10 years. We invest less in need-based aid per full-time undergraduate than any Midwestern state. Ohio devotes less than it used to funding higher education, and less than other states. We now rank 41st in the share of our income that we spend funding higher education. Tuition has soared and we have the sixth highest share of graduates leaving with debt and the ninth highest average debt load.

Deep investments in all of these areas would mean rehiring teachers and other school personnel we’ve laid off and bringing on ambitious young people struggling to find a foothold in our economy. It would mean that many people in Ohio would be better positioned for their own educational and eventual job success.

Another area ripe for investment is in conservation and green energy. We spend a lot on energy in Ohio (about 10% of our gross state product). We waste a lot of energy in our inefficient electrical grid, fuel-guzzling cars, and leaky buildings. We lose nearly 70 percent of energy during generation and transmission – basically throwing out two out of every three lumps of coal we use and wasting nearly $20 billion a year. And we pollute a lot.

We put in place clean energy standards in 2008, in a carefully-crafted bipartisan compromise. The policy worked, helping utilities invest in clean energy, create jobs, generate a market for renewables, and reduce consumption of polluting, largely imported fossil fuels. Utilities were producing and buying more wind and solar, and instituting programs to help manufacturers, businesses and households reduce consumption and upgrade their buildings.

We just became the first state ever to freeze clean energy standards. Instead of going backward, we should be insulating every public building in Ohio, doing it with union labor, and working with the building trades to create opportunities for a more diverse building trades workforce as we do so. Programs could help weatherize the home of every low-income family who struggles with high energy costs.

We should also encourage utilities to let private building owners retrofit and finance it off of the savings on their energy bills, bringing lower costs for owners and job creation for insulators, solar panel producers, and construction workers. Utilities in at least 23 states are doing or getting ready to do some form of this.

Transit is another crucial way to green the economy while delivering other benefits. In 2010, Ohio tied with South Dakota for the eighth lowest investment of state-source funds among the 46 states that put money into transit. Promoting transit increases vibrancy, reduces use of polluting fossil fuels, employs people, and makes it easier for poor families, who can’t afford a car, to keep a job.

Both human capital and efficiency investments reduce future public costs, reduce waste (of both people and resources), employ people now and make our lives better – our kids higher achieving, our workforce more productive, our air less polluted, our asthma rates lower and our planet’s climate less chaotic.

Ohio and the United States have taken on and solved more difficult problems than these, at times when we were much poorer than today. We transformed this country from one where only about one in four Americans had even a high school degree to one where 80 percent have a high school degree and close to one in three have a college degree. We got rid of slavery and Jim Crow, passed the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act, cleaned up our rivers and waterways and nearly eliminated once-staggering poverty among the elderly.

Given these accomplishments, we can figure out how to employ more Ohioans and deliver high quality education from pre-K to college, generating more productive Ohioans for the next generation. We can also implement clean energy standards that deliver jobs while improving efficiency. We just have to want to do it.

Acknowledgements

For substantial assistance with data and charts, we thank Avery Winston, Robert McCarthy and Hannah Halbert at Policy Matters Ohio and David Cooper at the Economic Policy Institute.

[1] Berger, Noah and Peter Fisher Well Educated Workforce is Key to State Prosperity at http://www.policymattersohio.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/EducationProsperity.pdf

[2]If we instead use the Ohio Department of Administrative Services data, based on actual payroll records instead of a survey and covering only state employees not university staff, Ohio also lost state jobs in the last several years http://das.ohio.gov/Divisions/HumanResources/HRDOCBPolicy/StateEmployeeData/StateEmployeeTrendReports.aspx

Tags

2014Amy HanauerEconomic DevelopmentMichael ShieldsState of Working OhioPhoto Gallery

1 of 22