State of Working Ohio 2012 (executive summary)

August 27, 2012

State of Working Ohio 2012 (executive summary)

August 27, 2012

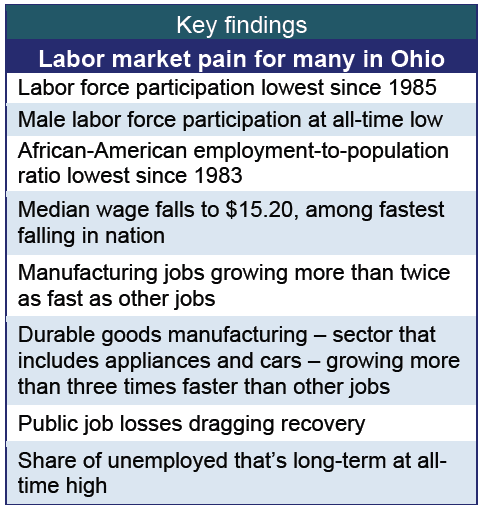

Our comprehensive review of the Ohio labor market finds that the median wage is dropping, job growth is far too slow, the labor market facing the black community is in crisis, and labor force participation is falling for all demographics and to historic lows for  some groups. Three years into what should be a strong recovery, Ohio workers are not getting what they need from the public or the private sector.

some groups. Three years into what should be a strong recovery, Ohio workers are not getting what they need from the public or the private sector.

Key findings include:

Modest job growth

- Over the last 12 months, the state job total has grown by 100,300 jobs, or 2 percent. At that rate, it will take more than two years to generate the 233,300 jobs needed to return Ohio to pre-2007 recession levels of employment and even longer to get to year 2000 levels. Nonetheless, the number of jobs has finally begun to pick up slightly in Ohio.

- Layoffs of local public sector workers are slowing Ohio’s recovery. If Ohio had avoided cuts to local public jobs since the end of the 2007 recession in June 2009, an additional 35,400 Ohioans would be employed.

- Ohio manufacturing climbed from a low of 609,900 jobs in November 2009 to 663,500 jobs in July 2012, a solid 8.8 percent growth over 33 months. Durable goods manufacturing, which produces appliances, cars and car parts, added 47,600 of those positions, an 11.9 percent growth in this subsector. Ohio jobs overall grew by just 3.6 percent over this period.

Leaving the labor force

- Ohioans continued to leave the labor force last year – more than 182,000 since the recession began. In 2011, only 64.1 percent of Ohioans were in the labor force, the lowest since since 1985.

- Ohio female labor force participation has fallen for four years and is at only 58.6 percent, lower than at any point since 1995. Male labor force participation has been declining since 1979 to last year’s all-time low of 69.9 percent, down ten percentage points since 1979.

- The unemployment rate fell for the last two years in Ohio and has fallen further since January. The rate was 8.7 percent annually in 2011 and at a 7.2 percent monthly rate in June and July 2012.

Unemployment

- The employment-to-population ratio of black workers last year was at just 48.6 percent, lower than at any point since 1983. Despite drops in labor force participation that keep discouraged workers out of the unemployment statistic, African Americans in Ohio were unemployed at an alarming 17 percent in 2011. Full-year unemployment had not been that high since 1986 in the black community.

- The share of the Ohio unemployed that’s been jobless for more than half a year rose to an all-time high of 44.2 percent in 2011, up from 42.4 percent in 2010. The prior peak was 30.2 percent in 1984.

- Last year 3.8 percent of workers had been jobless for more than half a year, 4.9 percent for less and another 4.9 percent stuck in part-time jobs. These contributed to underemployment of 14.7 percent, lower than the last two years but higher than at any other point since before 1994, when this measurement was started.

Inequality and wages

- The top 1 percent of Americans owned more than one-third (35.6 percent) of U.S. wealth in 2009 and the top 5 percent owned nearly two-thirds (63.5 percent). The bottom 80 percent own a tiny and shrinking share, down from 18.7 percent in 1983 to 12.8 percent in 2009.

- In just the last calendar year, Ohio’s median worker saw a 45-cent drop, in inflation-adjusted dollars, from the 2010 median wage of $15.65 (in 2011 dollars) to $15.20.

- Ohio real wage loss over the 2000s was among the highest in the U.S., second only to Michigan. Ohio’s median wage fell by $1.33 between 2000 and 2011, while Michigan’s fell by $1.36 in inflation-adjusted 2011 dollars. By contrast, states with fast-growing wages over that period included D.C. (+$3.54), North Dakota (+$2), Wyoming (+$1.93) and Massachusetts (+$1.41).

- Ohio is now well below average in median wage – tied with Maine for 30th highest median wage among states, at $15.20. The highest-earning states – in the $19 to $23 hourly range –– all have high levels of bachelor degree attainment, reasonable protection of collective bargaining and are diverse northeastern economies with large urban centers. The upper midwestern states whose economies resemble Ohio’s have wages ranging between $15.10 and $16.42. The lowest-wage states with wages from $13.84 to $14.53 have generally lower levels of education, much less unionization, more policies that hinder unions, and less urban and less diverse economies.

- Ohio workers with at least a bachelor’s degree earned $23.78 in 2011, $10 an hour more than workers with just some college, who earned $13.79 an hour. Still, wages are falling in most educational categories – dropping more than $2.00 per hour for workers with some college since 1979 and $5.84 for workers without a high school degree (in inflation-adjusted 2011 dollars).

- Ohio workers have increased their education levels. Of the labor force in 1979 just one third (33.6 percent) had some college or a BA compared to well over half (56.3 percent) by 2011. Nearly a quarter of Ohio workers hadn’t completed high school in 1979, but now more than 90 percent have. These levels remain behind those of the most affluent states like Massachusetts and Connecticut.

- In 2011, the median woman worker earned just $13.92 an hour, more than $3.00 less per hour than men ($17.08). Both male and female real median wages dropped for the past two years.

- The median black worker wage grew to $12.95 in 2011, but the gap is now 23 percent, much wider than in 1979. The median white worker earned $15.92 last year. This gap endures when controlling for education. At the median over the combined years 2009-2011, black workers with a BA earned $18.03 while whites earned $25.00; black workers with just a high school degree earned $11.62 while whites at that level earned $14.45 per hour.

- One way to address racial wage disparities is to encourage unionization. A union contract increases wages of black and white workers, and reduces the racial disparity from 22 to 17 percent.

The report concludes with recommendations to restore public employment and services, strengthen manufacturing, encourage education and unionization, and restore smart regulation.

Photo Gallery

1 of 22