Courting Crisis: Ohio Policy has Undermined Unemployment Compensation Fund

October 31, 2011

Courting Crisis: Ohio Policy has Undermined Unemployment Compensation Fund

October 31, 2011

If no action is taken to improve the solvency of Ohio's unemployment compensation trust fund, Ohio employers and the state itself will pay close to half a billion dollars in taxes and interest between September 2011 and the end of 2013. Ohio underfunded its UC system, leaving it among the states least prepared to face bad times and helping generate a $2.3 billion debt to the federal government. This October 2011 report concludes that after years of underfunding this crucial system, Ohio should face up to the need for more adequate financing and a higher taxable wage base.

If no action is taken to improve the solvency of Ohio's unemployment compensation trust fund, Ohio employers and the state itself will pay close to half a billion dollars in taxes and interest between September 2011 and the end of 2013. Ohio underfunded its UC system, leaving it among the states least prepared to face bad times and helping generate a $2.3 billion debt to the federal government. This October 2011 report concludes that after years of underfunding this crucial system, Ohio should face up to the need for more adequate financing and a higher taxable wage base.

Executive summaryFull report

Executive Summary

Ohio’s unemployment compensation trust fund – the money that pays benefits to unemployed Ohioans – has been broke for more than two years. If no action is taken, Ohio employers and the state itself will pay close to half a billion dollars in taxes and interest between last month and the end of 2013. Employers will find their unemployment taxes going up, beginning with a $21 charge for each employee making $7,000 in January 2012—and employers that have laid off the fewest employees will see the largest relative increases in tax rates. Already, the state has taken $70 million that had been intended first for anti-smoking programs and then for health and human-service programs and diverted it to pay interest on our $2.3 billion unemployment debt. If a long-term plan is not developed to begin rebuilding the fund, the state runs the risk of having a large, long-term debt to the federal government – a debt that will siphon off badly needed state resources, burden employers and could threaten the UC system, weakening coverage for jobless workers and reducing its positive effect on the economy.

Unemployment compensation not only provides a crucial backstop to jobless workers and their families – more than 3 million Americans avoided poverty in 2010 because of UC, according to the Census Bureau – it injects funds into the economy when they are most needed, acting as an automatic stabilizer. This eased the effects of the downturn.

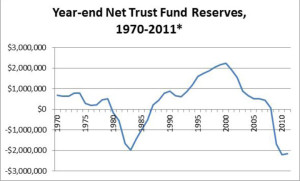

Ohio, however, has underfunded its UC system. For 11 out of the past 12 years, employers have paid less into the fund than was paid out in benefits. Like Ohio, more than half the states are borrowing from the federal government to pay unemployment benefits. But Ohio’s system was among the least prepared to face a serious recession.

Ohio’s trust fund has not met generally accepted solvency standards since 1974. Even in 2000, when Ohio had more than $2.2 billion in its fund, the state had less than two-thirds of the needed reserves to meet the benchmark, recommended by a nonpartisan federal commission. That year, 28 other states met the benchmark, while only six states had a poorer solvency position than Ohio. The situation was similar in 2007, as the recession began. Altogether, if Ohio employers had paid the average tax paid by employers across the U.S. between 1996 and 2006, the state trust fund would have received an additional $1.7 billion, or most of the deficit we currently face. While it’s not unreasonable that Ohio had to borrow during this period of high and long-term unemployment, it’s clear that Ohio’s UC solvency problem is not so much a product of the poor economy as much as poor policy.

Ohio employers pay taxes on only the first $9,000 in each employee’s annual wages, or less than a quarter of wages paid. That amount, which is well below the national average, hasn’t been raised since 1995; if it had risen with inflation since then, it would be $13,330. Sixteen states index their taxable wage bases, improving the likelihood that their trust funds will stay solvent.

Big increases in the number of unemployed and in long-term unemployment increased the benefit payout and contributed to the insolvency of the Ohio fund. Yet benefit levels – and the share of unemployed Ohioans who get benefits at all – are not high. The average weekly benefit is less than $300, below the U.S. average, and has fallen since 2008. While that represents a slightly higher share of average wages than in the country as a whole, it is not enough to keep a family of three above the official poverty line.

Ohio has persistently provided state benefits to a smaller share of its unemployed workers than does the average state. Recently, that share has fallen to a 25-year low of just 22 percent. Yet unlike most states, Ohio did not modernize its system to expand access to benefits and thus take advantage of a federal law that would have pumped $176 million into the state’s trust fund. We need to take measures to improve the share of Ohio unemployed who receive benefits—and avoid cuts to existing weekly benefit amounts or the 26 weeks that claimants can receive them. Ohio was able to avoid such draconian steps during the 1980s, when its debt was relatively higher than it is today, so those kinds of steps should not be needed now.

For the last year and a half, most Ohioans receiving unemployment compensation have been getting it because they have been out of work at least 26 weeks and qualify for benefits to the long-term unemployed paid by the federal government. Since mid-2008, the U.S. has injected $10 billion into the Ohio economy with UC aid, most of it through such extended benefits. However, these benefits are set to be phased out next year if Congress does not approve their extension. More than 57,000 Ohioans face a cut-off of such benefits in January 2012, according to the National Employment Law Project. These benefits need to be maintained.

A report commissioned by the state in 2007 on the solvency issue contains recommendations that would take the state a long ways toward a solid fund. Representatives of Ohio employers and employees made proposals in 2008 to tackle the solvency question, and while they did not reach agreement, their discussions then also provide a basis for a solution. Each of these included an increase in the share of wages being taxed, a temporary freeze on maximum benefits, and a surtax to help pay interest on the debt, as 22 states already provide for in their laws (that way, interest costs fall on employers, as they should, not individual taxpayers).

Legislation introduced in the U.S. Senate would give the states and employers a two-year breather on paying interest and the debt, and provide a long-term path to solvency. Ohio employers on average pay less than a penny for each dollar of wages in unemployment tax. After years of underfunding this crucial system, Ohio needs to face the need for more adequate financing and a higher taxable wage base, in particular.

Press release Executive summary Full report

Press coverage

Photo Gallery

1 of 22