Avoiding Accountability: How charter operators evade Ohio’s automatic closure law

January 09, 2013

Avoiding Accountability: How charter operators evade Ohio’s automatic closure law

January 09, 2013

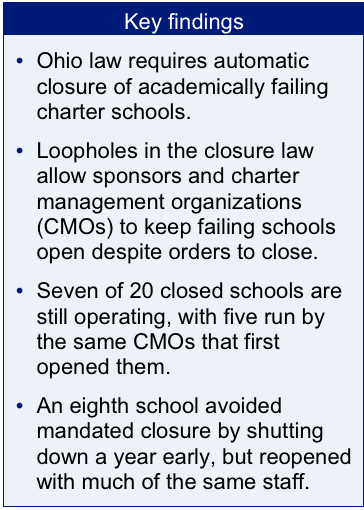

Executive summaryThe ability of schools and their management companies to skirt Ohio law reveals a systemic flaw in charter oversight. Until Ohio strengthens its charter-closure law, the state will continue to fall short of the goal of improving public education for all Ohio’s children.

Download reportPress release

Introduction

Ohio’s charter-closure law is touted as one of the toughest in the nation because it requires the automatic closure of charter schools that consistently fail to meet academic standards. The law has been showcased by the National Association of Charter School Authorizers (NACSA) in its “One Million Lives” campaign, which calls for tougher state laws to close failing charter schools.[1]

Ohio’s charter-closure law is touted as one of the toughest in the nation because it requires the automatic closure of charter schools that consistently fail to meet academic standards. The law has been showcased by the National Association of Charter School Authorizers (NACSA) in its “One Million Lives” campaign, which calls for tougher state laws to close failing charter schools.[1]

The widespread attention and support of the NACSA campaign has pushed Ohio’s closure law into the spotlight as a model of accountability for low-performing charter schools. However, The Plain Dealer’s editorial board, in a commentary on NACSA’s praise of Ohio’s charter school accountability standards, pointed out what NACSA did not: Ohio’s charter school laws, while they may have stronger mandates for closure than those of other states, are still replete with loopholes.[2] Since the charter-closure law went into effect in 2008, 20 schools across the state have met closure criteria, and all are currently listed as closed by the Ohio Department of Education (ODE). But an investigation of the schools by Policy Matters revealed that eight schools – and the management companies that run them – have found ways to skirt the closure law and remain open, severely undermining the law’s effectiveness and highlighting the lax accountability that prevails in Ohio’s charter sector. For-profit managers – the Leona Group, Mosaica Education and White Hat Management – operate six of the reopened schools

Automatic closure

Ohio’s charter-closure law, which became effective in 2008 and was revised in 2011, calls for automatic closure of schools rated in Academic Emergency for at least two of the three most recent school years. To be subject to the law, charters serving grades four through eight also must show less than one year of academic growth in either reading or math in that time period.[3]

Oversight of these criteria primarily falls on authorized sponsors, which are responsible for evaluating and reporting on the academic and financial performance of their sponsored schools, and on ODE. The automatic closure law calls for schools meeting the criteria to be closed permanently, and it requires the school’s sponsor and its governing authority to comply with state-mandated procedures for closing the school. The law forbids the governing authority (the school board) of a school marked for automatic closure from entering into a contract with any other charter school sponsor after the school closes.[4]

The loophole in the law

Despite tough legislation, weak oversight of Ohio’s charter sector continues to allow evasion of the closure law by charter management organizations (CMOs). While Ohio law sets up charter school boards as the entity to be held legally responsible for a school’s academic and financial performance, it does not do the same for management companies, many of them for-profit, that are contracted by schools to manage their daily operations. These companies are often in charge of making major decisions for a school, including hiring and firing teachers, assessing academic performance, contracting with vendors, budgeting, developing curriculum, and providing basic classroom materials. Yet the closure law places no penalty on CMOs when their schools meet academic closure criteria. This omission creates a loophole for managers to keep “closed” schools open and continue to receive public funds for failing schools.

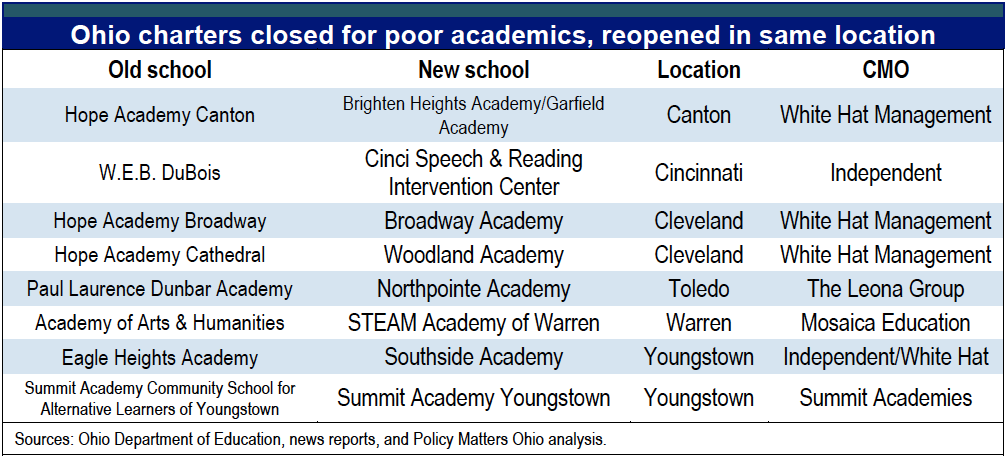

Policy Matters Ohio examined charter schools on ODE’s closure list and found that several – all but one managed by CMOs – are still open despite their “closed” status. For-profit CMOs run six of the schools, the non-profit Summit Academies operates one, and the last is independently operated. While these schools have new names, Policy Matters discovered that the old, closed schools and the new schools opened in their places had significant – in some cases nearly complete – staff overlap, and that all the new schools remained at the same address where the old schools had operated. Table 1 provides an overview of these schools, along with their location and CMO.

Closing failing charters

In February 2011, Policy Matters reported on the required closure of Paul Laurence Dunbar Academy, a K-8 charter school in Toledo operated by the Leona Group, a Phoenix-based, for-profit management firm.[5] Paul Laurence Dunbar Academy was placed on the state’s closure list for poor academic performance and was required to be shut down by the end of June 2010; however, by July 2, 2010, the Leona Group had opened a new school, Northpointe Academy, at the same location and with much of the same staff. The Leona Group’s re-opening of Paul Laurence Dunbar Academy under a new name is just one of several cases in which charter management companies have skirted Ohio’s automatic closure law. This paper examines these cases to show how charter schools are being kept open in spite of consistently failing academic records.

Since the Ohio legislature first established charters in Ohio, the state has taken a quantity-over-quality approach to approving new schools and allowing troubled schools to continue. National studies that have included Ohio have found that overall, the majority of charter schools do no better than demographically comparable district counterparts.[6] The state’s closure law was put in place to deal with the glut of ineffective charter schools that have for too long betrayed the promise of charters in Ohio. But our investigation shows that despite its seemingly strict closure law, Ohio still falls short of the meaningful oversight and accountability needed to improve the state’s charter sector.

Until legislators and the charter sector in Ohio begin to take accountability and academic quality more seriously, families and children that would benefit most from quality education will be ill-served by Ohio’s charter schools.

Case No. 1: Eagle Heights Academy

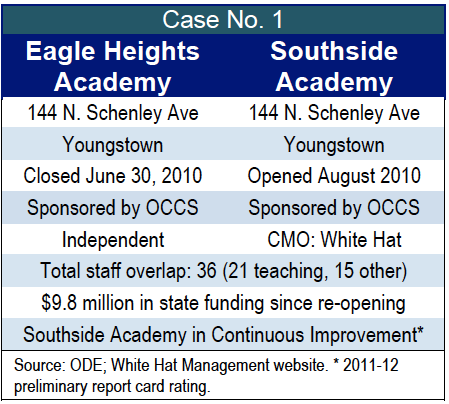

Eagle Heights Academy, a K-8 charter school in Youngstown, was required to close by the end of June 2010 due to consistent Academic Emergency ratings. Ohio Council of Community Schools (OCCS) sponsored the school, which was located at 1833 Market Street in Youngstown. The Ohio Department of Education lists its official closure date as June 30, 2010.[7]

Within days of Eagle Heights’ closing, a new school serving grades K-8, Southside Academy, was set to open at the same location. When Southside Academy opened for the 2010-11 school year, it had the same sponsor, OCCS, and retained the Eagle Heights principal and 36 of its staff members, including 21 teachers, aides, and instructional support staff.[8] Unlike Eagle Heights, which was independently operated, Southside Academy contracted Ohio’s largest charter school operator, the for-profit White Hat Management, to run the school. Despite the new name and management, the use of the same building and staff raise the question: Would the typical observer consider Southside Academy a new school, or would it simply appear to be the same school with a new name?

In addition to its academic shortcomings, in May 2010, the state auditor found “extensive fiscal mismanagement” at Eagle Heights Academy and declared a lack of proper financial oversight at the school – oversight that according to Ohio charter school law should have been provided by OCCS, the school’s sponsor. The mismanagement included $454,381 in federal income tax and Medicare withholdings never given to the IRS, over $700,000 in questionable costs, and $33,500 of illegal one-time payments to 29 employees from a federal grant.

In the three years prior to closure, Eagle Heights received over $18 million in state funding. Southside Academy has taken in over $9.8 million since its opening in 2010.[9]

Case No. 2: Paul Laurence Dunbar Academy

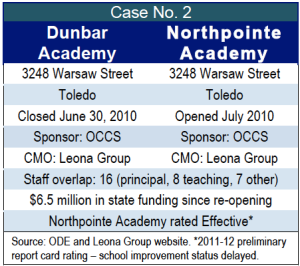

Paul Laurence Dunbar Academy, a Toledo charter school serving grades K-8, was ordered to close by the end of June 2010 for consistent academic failure. Like Eagle Heights Academy, Dunbar was sponsored by OCCS. It was operated by the Leona Group, a for-profit charter management company based in Arizona. Between 2007 and 2010, Dunbar Academy received $3,686,910 in state funding.

ODE marked Dunbar’s closing date as June 30, 2010, but by July 2, 2010, the Leona Group had already opened a new school, Northpointe Academy, at the same Warsaw Street site. Northpointe Academy, also sponsored by OCCS, was originally another Leona Group school, Great Lakes Environmental Academy (GLEA), which served grades 7-12 at a different location. During the 2009-10 school year, GLEA’s name was changed to Northpointe Academy (the school’s state-issued identification number, or IRN, remained the same), and Northpointe took over Dunbar’s location, 3248 Warsaw Street in Toledo. The staff and administration of GLEA, however, stayed behind and became the 7-12 expansion of another Leona Group school, Wildwood Environmental Academy, while the principal and 15 staff members of Dunbar Academy moved into nearly identical positions at Northpointe Academy without moving to a new address.[10]

In a March 2011 Toledo Blade article, an ODE spokesperson called the Leona Group’s actions “legal.”[11] Northpointe Academy, which now serves grades K-6, still employs 14 staff members from Dunbar Academy, including Principal Andre Fox. The school’s enrollment jumped significantly in 2010-11 but fell after dropping grades seven and eight last year; it has also improved from Academic Watch to Effective.[12] Since 2010, Northpointe Academy has received just over $6.5 million in state funding.

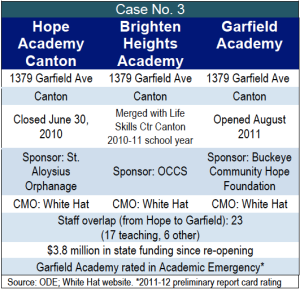

Case No. 3: Hope Academy Canton

Hope Academy Canton, a K-8 charter school in Canton, was ordered to close in June 2010 by its sponsor, St. Aloysius Orphanage, which did not renew its contract because of the school’s poor academic performance. Operated by the for-profit White Hat Management, Hope Academy Canton failed to rate higher than Academic Watch and was at risk for being closed by the state for academic failure. In the three years prior to closure, the school received nearly $7.4 million in state funding.

Instead of closing in June 2010 as ordered, however, Hope Academy Canton was kept alive through the expansion of another White Hat-operated school, Life Skills Center Canton, a dropout-recovery program. Under the expansion, the schools merged to become Brighten Heights Academy, operated by White Hat and sponsored by Ohio Council of Community Schools (OCCS).[13] Despite its status as a single school, Brighten Heights maintained the two existing campuses: a high school at the former Life Skills Center location (1100 Cleveland Ave NW) and a K-8 at the former Hope Academy site (1379 Garfield Ave. SW). Twenty-one staff members from Hope Academy Canton, including 19 teachers and aides, stayed on at Brighten Heights.

The merger between Hope Academy Canton and Life Skills Center Canton lasted for one school year, during which Brighten Heights received a rating of Academic Watch and took in $3 million in state funding. By the 2011-12 school year, Life Skills Center Canton was back to its original name, and a new school, Garfield Academy, took the place of the Brighten Heights K-8 school. Garfield Academy is one of White Hat’s Hope Academies, just like Hope Academy Canton.

Ohio law prohibits boards of charter schools shut down by the state’s closure law from contracting with a new sponsor, and the same five-member school board that ran its predecessor, Hope Academy Canton, governs the new Garfield Academy. But since Hope Academy Canton was ordered to close by its sponsor, St. Aloysius, and was still a year away from meeting the state’s automatic closure criteria, Garfield Academy’s board members are not technically in violation of the law for contracting with Buckeye Community Hope Foundation as its sponsor.

It must be noted, however, that the decision to merge schools and subsequently create a new school in the same location on Garfield Avenue allowed White Hat Management, and the board members, to avoid the looming closure that Hope Academy Canton’s poor academic performance was about to trigger. In receiving a new charter for Garfield Academy, White Hat is assured of at least five more years of operation even though it is essentially the same school, with much of the same staff, that existed under the name of Hope Academy Canton. Twenty-eight Brighten Heights Academy staff members were on the 2011-12 Garfield Academy staff list, and 23 of those – of a total staff of 32 – had been employed at Hope Academy Canton.

Improved academic outcomes have not been a part of this story. Garfield Academy was rated in Academic Emergency last year. Since its opening, the school and its management company have taken in more than $3.8 million in state funding.

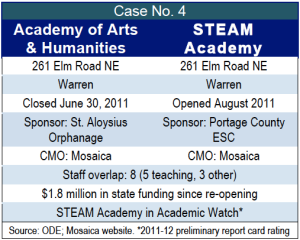

Case No. 4: Academy of Arts & Humanities

Academy of Arts & Humanities, a K-8 charter school in Warren, became subject to the closure law in 2011 after repeated Academic Emergency ratings. Sponsored by St. Aloysius Orphanage and operated by the for-profit charter management company Mosaica Education, the Academy of Arts & Humanities received over $6.5 million in state funding from 2007 to 2011. According to ODE records, the school closed on June 30, 2011. Mosaica is an international company with offices in New York and Atlanta that runs schools across the U.S., in Britain, the United Arab Emirates and India.

When ODE forced the closure of the Academy of Arts & Humanities, Mosaica started, at the same location, the STEAM Academy of Warren in time for the 2011-12 school year. Sponsored by Portage County Educational Service Center, STEAM Academy (for Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Math) opened its doors with eight staff members from Academy of Arts & Humanities. The new school has received ratings of Academic Emergency and Academic Watch over the past two school years and received over $1.8 million in state funding since 2011.

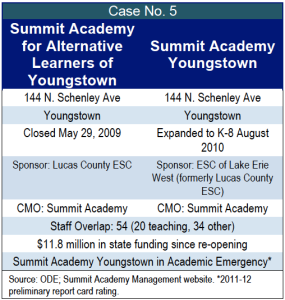

Case No. 5: Summit Academy Community School for Alternative

Learners of Youngstown

Summit Academy Community School for Alternative Learners of Youngstown, a K-8 charter school, opened with the mission of providing an education alternative for students with mild to moderate learning and behavior disabilities. Located at 144 N. Schenley Avenue in Youngstown, the school was operated by the non-profit Summit Academy Management and sponsored by Lucas County Educational Service Center. After three consecutive years in Academic Emergency, the state required Youngstown’s Summit Academy to close by the end of June 2009. According to ODE records, it officially closed its doors on May 29, 2009.

Although the school building was closed in May 2009, Summit Academy Management was able to keep its Youngstown K-8 school open by adding grade levels to one of its existing schools, Summit Academy Middle School – Youngstown. In 2008-09, the middle school, located at 810 Oak St. in Youngstown, served grades 6-8; by the following school year it had expanded to grades K-8 and was re-named Summit Academy Youngstown. By the 2010-11 school year, the expanded and newly renamed Summit Academy Youngstown moved to its current location, 144 N. Schenley Ave, the former site of Summit Academy Community School of Alternative Learners of Youngstown, the K-8 that had been closed by the state.

A review of ODE records revealed that in the 2009-10 school year, Summit Academy Youngstown employed 54 staff members that had been employed at Summit Academy Community School for Alternative Learners of Youngstown during the 2008-09 school year. In fact, during 2008-09, the two schools shared 63 staff members, mostly in administrative positions, and after the merger, half of Summit Academy Youngstown’s teaching staff were teachers and aides from Summit Academy Community School for Alternative Learners of Youngstown.

Summit Academy Management currently operates 26 charter schools in Ohio. Lucas County Educational Service Center, which has since merged into the newly created sponsor known as Educational Service Center of Lake Erie West, was the sponsor of both schools before the merger and continues to sponsor Summit Academy Youngstown, as well as 23 other Summit Academies across the state. In the three years prior to required closure, Summit Academy Community School for Alternative Learners of Youngstown received just over $7.3 million in state funding. Since the school merger in 2009, Summit Academy Youngstown remains in Academic Emergency and has taken in over $11.8 million in state funds.

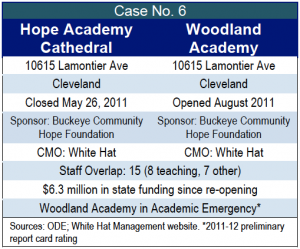

Case No. 6: Hope Academy Cathedral

Hope Academy Cathedral, a White Hat-operated charter school in Cleveland, was ordered closed in 2011 after three consecutive years in Academic Emergency. Located at 10615 Lamontier Ave, Hope Cathedral served grades K-8 and was sponsored by Buckeye Community Hope Foundation. In the three years before ODE required it to close, Hope Cathedral took in nearly $12 million in state funds. According to ODE’s list of closed schools, Hope Cathedral closed on May 26, 2011.

Less than two months later, the for-profit White Hat sent out a press release announcing the opening of a new school, Woodland Academy, at the same Lamontier Avenue location. Also serving grades K-8, Woodland Academy held its grand opening on July 16, 2011, providing free handouts and entertainment to prospective students and families in addition to promising “a special guest from the Mayor’s office.”[14] When Woodland Academy opened for the 2011-12 school year, 15 former Hope Cathedral staff members, including 8 teachers, were on the staff roster. Like Hope Cathedral, Buckeye Community Hope Foundation sponsored Woodland. Woodland received a rating of Academic Emergency in its first year and has received over $6.3 million in state funding since opening.

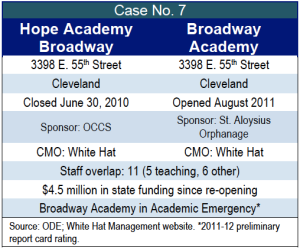

Case No. 7: Hope Academy Broadway

Hope Academy Broadway, another White Hat-operated charter school, served grades K-8 until being ordered closed in June 2010 for repeated academic failure. Hope Broadway was located at 3398 E. 55th St. in Cleveland and was sponsored by OCCS. From 2007 to 2010, the school received more than $10 million in state funds.

Hope Broadway closed its doors a year earlier than required because its board could not find a sponsor for the 2010-11 school year. By the following school year, however, a new charter school, Broadway Academy opened its doors at the former Hope Broadway site.[15] Sponsored by St. Aloysius Orphanage, Broadway Academy is a K-8 school operated by White Hat. It retained 11 former Hope Broadway staff members and added three former Hope Cathedral teachers to its roster.

Broadway Academy received a rating of Academic Emergency in 2011-12, and has taken in more than $4.5 million in state funding since opening.

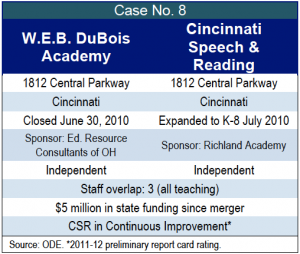

Case No. 8: W.E.B. DuBois Academy

W.E.B. DuBois Academy, an independently run Cincinnati charter school serving grades four to eight, was placed on ODE’s closure list in 2009 after three straight Academic Emergency ratings. It received more than $3.6 million in state funds from 2007 to 2010. According to ODE records, DuBois Academy, sponsored by Educational Resource Consultants of Ohio, closed on June 30, 2010.

Despite the state-mandated closure, the Cincinnati Enquirer reported in June 2010 that the DuBois Academy board had other plans. Edward Burdell, a DuBois board member, told the Enquirer DuBois’ sister school, Cincinnati Speech and Reading Intervention Center (CSR) would expand from K-3 to K-8 and move into the DuBois Academy building to accommodate its student population.[16] Prior to its 2010 required closure, DuBois Academy had its share of controversy. Once celebrated for its academic achievement, the school originally announced it would close in May 2006 due to financial difficulties stemming from over-payment by the state for DuBois’ extended school year. School officials said the school could not survive on the corrected aid amount and would be unable to repay the $3 million it was overpaid.[17] After contracting with a new sponsor, DuBois Academy was kept open, only to have its founder, Wilson Willard indicted, and later convicted, on charges of theft and record-tampering. Willard falsified student enrollment records in order to receive more state funding and used public funds meant for the school to renovate his home. A 2009 Ohio Auditor report revealed Willard and another school employee cheated the school and state taxpayers for more than $700,000.[18]

Records for both DuBois and CSR reveal a pattern of high teacher turnover in recent years. The 2010-11 CSR staff list shows only three of eight CSR teachers from 2009-10 remained employed by the school. Three DuBois Academy teachers were also on the 2010-11 CSR staff list. CSR was rated in Academic Watch in 2007-08 and was not rated by ODE from 2008 to 2010. After the expansion to K-8 in 2010-11, it received a rating of Academic Emergency for one year before moving to Continuous Improvement in 2011-12. CSR has taken in just over $5 million in state funding since its 2010 merger with DuBois Academy.

Letting CMOs and sponsors off the hook

It requires no great leap of logic to conclude that CMOs hold a great deal of responsibility for a school’s academic failings, but as this study shows, management companies running failed charter schools have been able to escape responsibility time and time again. For-profit management companies – the Leona Group, Mosaica Education, and White Hat Management – run six of the eight schools investigated for this report. White Hat, a repeat offender that has kept a number of failed schools open, was sued in 2010 by the boards of 10 White Hat-managed schools (including Hope Academy Cathedral and Hope Academy Broadway), partly on the grounds that it was abusing the “unchecked authority” granted to charter managers in state law.[19] The controversial law permits sponsors to remove a charter school governing board if the board decides to terminate a contract with its CMO, and gives the company the right to appoint a school board to its liking and continue management of the school.[20] Ohio’s law gives too much power to sponsors and CMOs. The law makes it difficult to have strong, independent charter school boards that can make decisions based on the best interest of their students. It also allows for uncomfortably close relationships between sponsors and charter managers, both of which have strong financial incentives to maintain a school’s operation regardless of its academic performance.

CMO accountability was further diminished in 2011 when Ohio legislators repealed Ohio’s “highly qualified operator” provision. The repeal gives new start-up charter schools the option of contracting with CMOs that do not meet previously prescribed performance standards, effectively eliminating academic accountability for CMOs.[21] Unfortunately, these recent legislative changes are reflective of Ohio’s weak regulation of CMOs, which continue to receive a free pass from state lawmakers. Similarly, aside from losing revenue – up to 3 percent of the state funding of schools they authorize – sponsors are not penalized when schools are closed under their watch.[22] Sponsors can have their right to authorize new schools taken away if ODE finds them non-compliant with reporting requirements, or if the composite performance index of their schools puts them into the lowest 20 percent of sponsors.[23] Of the sponsors in this study, Richland Academy and Portage County ESC are in the bottom 20 percent and are no longer allowed to sponsor new schools; they do maintain sponsorship of schools already under contract.[24]

SB 316, passed by the Ohio General Assembly in June 2012, conceded the lack of accountability for sponsors, and new legislation on charter school sponsorship accountability is currently being considered.[25] The proposed legislation, HB 555, would go into effect for the 2015-16 school year and adds components on the sponsor’s adherence to quality practices and standards. It leaves the responsibility of determining the practices and standards that sponsors will be measured by to ODE and the state school board, but the legislation currently includes language that would give ODE the right to revoke sponsorship rights from non-compliant sponsors.[26] This is a step in the right direction, but we will not know how effective the new accountability measures will be until the new sponsor rating system is unveiled.

Conclusion

Policy Matters has documented that of the 20 charter schools ODE has required to close for academic reasons, seven have essentially remained intact, skirting the automatic closure law.[27] In some cases, management companies have expanded the charters of other schools to incorporate grade levels served by closed schools – a practice deemed legal by ODE. In other cases CMO-operated schools facing automatic closure were replaced by nearly identical schools, managed by the same company with much of the same staff. An eighth school, Hope Academy Canton, was ordered closed by its sponsor a year before it would have been shut down by the state. In this case, our investigation showed that by closing early and opening a new school in the same location with much of the same staff, the schools’ for-profit operator, White Hat Management, bought five additional years of life – and revenue – for a low-performing school. In more than half the cases we examined, the new schools’ academic performance remained the same as the old schools’; five of the eight “new” schools are still ranked in Academic Watch or Emergency, while their management companies and sponsors continue to take in millions of dollars in public funding. For-profit CMOs – the Leona Group, Mosaica Education, and White Hat Management – run six of the eight schools we investigated. The non-profit Summit Academies runs one, and one is operated independently.

Despite the appearance of being tough on academically failing charter schools, Ohio’s automatic closure law has glaring loopholes that undermine its effectiveness and the overall quality of its charter schools. Because it holds only charter school boards responsible for academic failure, the law allows sponsors and CMOs to evade accountability and keep poorly performing schools open. Our investigation shows that Ohio’s charter-closure law is at best a superficial attempt to close poorly performing schools and improve Ohio’s charter sector; by failing to set firm consequences for sponsors and CMOs, the law only succeeds in punishing students. Charter advocates and education reformers speak often of doing what’s best for children, not for adults, but in light of the evidence, these words sound like little more than empty rhetoric, at least in Ohio.

Ultimately, responsibility lies with Ohio policymakers for refusing to hold sponsors and CMOs accountable for the academic failures of their schools. Ohio’s lawmakers have given too much power to CMOs, while simultaneously absolving them of responsibility. Also at fault is ODE, which by turning a blind (and understaffed) eye, and on at least one occasion recognizing loopholes as “legal,” has allowed questionable practices by sponsors and CMOs to go unchecked. Ohio’s charter-closure law will never be tough enough without provisions placing the burden of accountability on CMOs. Until the closure laws are strengthened, sponsors must do more to ensure that schools facing closure are closed. Sponsors, in continuing to approve contracts that put the reins of new schools back in the hands of the CMOs that failed in the first place, violate the spirit of the law and weaken the efforts to hold charter schools accountable for their academic performance. There is no excuse for those who keep failed charter schools open, and it is time for policymakers and charter advocates to take real action against those who do.

Recommendations

In the 2010 report, “Authorized Abuse: Sponsors, Management, and Ohio Charter School Law,” Policy Matters Ohio called for an overhaul of Ohio charter school law to increase standards for more effective sponsor oversight of management-school board relationships.[28] This study provides further proof that Ohio’s charter school laws do not provide the necessary framework for meaningful oversight of the charter sector.

Based on this study, Policy Matters Ohio recommends the following:

- Revamp the closure law – Legislators must change the law to include accountability measures for the sponsors and charter management organizations of schools meeting closure criteria. The reworked law should ensure that sponsors, CMOs and school boards do not sign new contracts that circumvent the closure of academically failing schools.

- Strengthen oversight – ODE’s capacity to oversee closure of charter schools is woefully inadequate. The department should have, and exercise, increased capacity to provide meaningful oversight. This should include the power to refuse the expansion of charter contracts, which has allowed charter managers to merge closed schools with other schools they run. Legislators, ODE, and the state school board must also push forward on proposed legislation to better measure sponsor performance, increase accountability of sponsors, and revoke the approval of non-compliant sponsors. ODE and the state board, as they promote quality practices and standards for charter sponsors, should include tough penalties for sponsors that help keep failed charter schools open.

- Hold charter managers accountable – Ohio’s charter closure law does not reflect the considerable role CMOs play in the failure of a charter school, leaving management firms free of blame and, even worse, free to manage new schools despite their failures. Ohio lawmakers need to push for stronger accountability measures for charter management organizations and push out those that have a history of academic failure and non-compliance. It is unfortunate that in 2011 the legislature repealed the relatively weak operator provision that kept charter managers with no schools rated at least at Continuous Improvement – the equivalent of a C grade – from authorizing new schools. This represents a step in the wrong direction for Ohio’s charter sector; policymakers should have made the operator provision tougher, not weaker.

Charter law in Ohio remains ineffective and weak. Until Ohio gets serious about quality in the charter sector – both on the front end, by preventing operators with weak track records from opening new schools, and by creating a more meaningful charter-closure law – Ohio will continue to fall short of the goal of strengthening its public education system so that it can serve everyone.

[1] NACSA press release on 11/28/12: “A Call for Quality”

[2] “Tougher charter school standards praised – by charter group: editorial” The Plain Dealer. November 28, 2012. http://www.cleveland.com/opinion/index.ssf/2012/11/tougher_charter_school_standar.html

[3] This provision applies only to schools serving children in grades four to eight because Ohio’s standardized testing measures academic progress only in those grades and only in reading and math.

[4] Ohio Revised Code 3314.35 http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/3314.35.

[5] “Toledo charter school re-opening skirts Ohio law.” Policy Matters Ohio 15 February 2011. http://www.policymattersohio.org/toledo-charter-school%C2%A0re-opening-skirts-ohio-law

[6] See, for example, Rand Corporation, Charter Schools in Eight States, at http://bit.ly/XFfchX and CREDO/Standford University, Multiple Choice: Charter School Performance in 16 States, at http://credo.stanford.edu/research-reports.html.

[7] All school data found in the Ohio Department of Education’s Annual Reports on Ohio Community Schools and its Directory of Community Schools and Sponsors, online at http://bit.ly/SiypcC.

[8] All school staff data found through ODE’s Power User Reports at http://ilrc.ode.state.oh.us/Power_Users.asp.

[9] All state funding amounts are from ODE’s Community School Payment Reports

[10] van Lier, Piet, “Charter School Re-opening Skirts Charter School Law,” Policy Matters Ohio, February 15, 2011. Retrieved at http://www.policymattersohio.org/?p=902.

[11] Rosenkrans, Nolan,“Origin of school questioned,” Toledo Blade, March 23, 2011, retrieved at http://bit.ly/XXntCV.

[12] All report card data found on ODE’s Interactive Local Report Card site, http://ilrc.ode.state.oh.us.

[13] Griffy Seeton, Melissa, “New name, new ‘Hope,’ but new school?,” Cantonrep.com, July 18, 2010 http://www.cantonrep.com/news/x1814121457/New-name-new-Hope-but-new-school

[14] White Hat Management press release http://www.wediducan.com/uploads/296001310397251.pdf

[15] White Hat Management press release http://www.wediducan.com/uploads/29321310397238.pdf.

[16] Brown, Jessica, “Two charter schools face closure,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 17, 2010.

[17] Elliot, S, “Cash crunch to close charter school darling,” Dayton Daily News blog Get On the Bus, May 27, 2006.

[18] Ohio Auditor of State press release, April 2, 2009 http://www.auditor.state.oh.us/newscenter/press/release/670/

[19] Marshall, Aaron, “10 Northeast Ohio charter school boards sue White Hat Management firm,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 18, 2010 http://www.cleveland.com/open/index.ssf/2010/05/for-profit_management_company.html

[20] Ohio Revised Code 3314.026 – Termination of contract with operator.

[21] Ulmer Berne LLP, H.B. 153 Community School Summary, retrieved at http://bit.ly/SX8QvN.

[22] Ohio Revised Code 3301-102-04 A(3). Sponsorship Agreement. http://codes.ohio.gov/oac/3301-102-04

[23] Ohio Revised Code 3301-102-07 – Revocation of sponsorship authority. http://codes.ohio.gov/oac/3301-102-07

[24] From the “Sponsor Composite Performance Index & Reporting Compliance” document found on the ODE website.

[25] From the Ohio Legislative Service Commission’s (OLSC) Final Analysis of SB 316. at http://bit.ly/Tdgpgy.

[26] From the OLSC Bill Analysis of HB 555, at http://www.lsc.state.oh.us/analyses129/h0555-i-129.pdf.

[27] ODE’s “List of Closed Schools” was retrieved at http://1.usa.gov/UauYUm.

[28] van Lier, Piet, Authorized Abuse: Sponsors, Management, and Ohio Charter School Law. Policy Matters Ohio, September 2010.

Tags

2013Former StaffK-12 EducationPhoto Gallery

1 of 22