The promise of Pre-K

September 28, 2016

The promise of Pre-K

September 28, 2016

Cincinnati ballot issue is critical to ensure access to preschool for all.

Cincinnati ballot issue is critical to ensure access to preschool for all.Contact: Michael Shields, 216.361.9801

By Michael Shields

Executive Summary

Quality preschool improves children’s educational outcomes into the elementary grades, and good programs with wraparound childcare anchor family financial stability by enabling parents to work. Yet, too few Cincinnati children have access to a good preschool or any preschool at all. A levy on this November’s ballot seeks to change that by adding a new local funding source for both preschool and K-12 education.

Quality preschool improves children’s educational outcomes into the elementary grades, and good programs with wraparound childcare anchor family financial stability by enabling parents to work. Yet, too few Cincinnati children have access to a good preschool or any preschool at all. A levy on this November’s ballot seeks to change that by adding a new local funding source for both preschool and K-12 education.Issue 44 asks voters to approve a $48 million per year - $33 million for K-12 schools and $15 million to expand access to quality preschool throughout Cincinnati. The proposal forges a partnership between parents, educators, the Cincinnati Public School District and Preschool Promise advocates. The proposal, which combines two separate initiatives, would fund preschool for all 4-year-olds and for some at-risk 3-year-olds. This would be transformative for children and families in Cincinnati.

A new report by Policy Matters Ohio lays out the current preschool landscape, discusses the challenges families now face to accessing quality early care and education, and identifies opportunities for the city to leverage new and existing funds to deliver top quality education to all Cincinnati young children and their families.

The report says families face barriers to quality programs because of cost. Available slots for quality programs and wraparound childcare are lacking, and good programs are located too far from neighborhoods where they are needed.

The report also discusses how investing in staff is a vital component in delivering a high quality center, and urges the city to devote resources from Issue 44 to teacher development and compensation.

Policy Recommendations

- Pass Issue 44 to increase resources for K-12 and undertake a broad initiative to build out quality preschool options for Cincinnati

- Restore initial eligibility for publicly funded childcare to 200 percent of poverty level.

- Boost reimbursement rates to the 75th percentile so that families can choose from an array of programs, including top-rated programs. The 75th percentile is the point that would meet the cost of the most affordable 75 percent of programs.

- Increase participation in quality ratings programs. Making Step Up To Quality rating mandatory is a step in the right direction. Delivering the resources programs need to make it work is the next step.

- Increase preschool offerings in public schools where quality is high and demand far exceeds capacity

- Explore partnerships between public preschools and good extended-hours childcare centers and home providers to provide the best pre-academic learning and wraparound care. Rate in-home providers using SUTQ.

- Invest in teachers. Substantially increase teacher pay to attract high quality staff with strong credentials, and keep them focused on their work.

Introduction

Quality preschool improves children’s educational outcomes into the elementary grades. Good programs with wraparound childcare anchor family financial stability today by enabling parents to work. Yet too few Cincinnati children have access to a good preschool or any preschool at all. A levy on this November’s ballot seeks to change that by adding new local funding source to available resources for both preschool and K-12 education.Issue 44 asks voters to approve a $48 million per year joint levy - $33 million for K-12 schools and $15 million to expand access to quality preschool throughout Cincinnati. The proposal forges a partnership between parents, educators, the Cincinnati Public School District and Preschool Promise advocates. The proposal, which combines two separate initiatives, would fund preschool for all 4-year-olds and for some at-risk 3-year-olds. This would be transformative for children and families in Cincinnati. This report focuses on the preschool component of the measure, lays out the current landscape, discusses the challenges families face accessing quality early care and education, and identifies opportunities to leverage new and existing funds to deliver top quality education to all Cincinnati young children and their families.

Cincinnati preschool today

Among Cincinnati’s more than 10,000 preschool-aged children, less than 46 percent attend a school or center-based early childhood education program.[1] Cost is a major barrier. The median household in Cincinnati earns just $34,002 per year, while the cost of center-based preschool is $9,372 at the median. Public preschool is a high-quality option that is more affordable at $6,800 per year, but gaps in hours and summertime breaks mean that working parents may face the added cost and logistical challenge of supplementing preschool with childcare through a different provider. Tuition for preschools with wraparound childcare is higher than the cost of rent for the typical Cincinnati family.

High costs create affordability challenges not just for poor families, but for most families with young children. Costs are a challenge to programs on the other hand too, which face challenges to provide high quality care and learning opportunities on tight budgets; some succeed, while others remain perpetually under-resourced. School districts offer high-quality public programs, but there are too few spots for all children, and limited wraparound services favor access to two-parent or flexible-schedule households. The solution is deep public investments in preschool-12 education, and an expansion of strong education infrastructure.

Cincinnati preschoolers in and out of preschools

As of the 2010 Census, there were an estimated 10,000 preschool-aged children living in Cincinnati, including five-year-olds not yet enrolled in Kindergarten.[2] While all of these children meet Ohio’s definition of “preschoolers” – an age category – only about 46 percent were enrolled in a formal program last year. The same Census report found that 4,593 children were in preschool or nursery programs in 2010. Childcare centers reported serving 4,269 of them in 2014-2015, while district-based programs served as many as 1,200. Since there is overlap in program use, it is not possible to sum these numbers. This report uses the Census figure, indicating that some 45.6 percent of Cincinnati preschool-eligible children were in full- or part-time preschool last year.

Because quality programs give children the core fundamentals they need to thrive in school, boosting access is vital. This is especially true for older preschoolers in their last year before entering school. The levy would enable Cincinnati to serve all four-year-olds, and some at-risk young preschoolers starting at age three.[3]

Preschool settings

Cincinnati preschoolers are in programs administered by either public school districts or private centers, many of which offer extended day childcare. Head Start programs may operate under either structure. District-run programs are licensed and inspected by the Ohio Department of Education, while non-district affiliated programs fall under the jurisdiction of the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services. The Cincinnati public school district operates 37 preschools under ODE, and ODJFS licenses 120 childcare centers that provide early childhood education in Cincinnati. Cincinnati child care centers reportedly served 4,269 preschoolers in 2014-2015. Around 1,200 attended preschool through the public schools.

Ohio lacks a uniform definition of preschool. While school districts provide structured programs with some consistency, childcare centers host an array of offerings all under the umbrella of “preschool.” Quality varies widely. Characteristics of a high quality program include staff who hold early childhood education credentials, especially college degrees; curriculum planning with emphasis on developmentally appropriate activities and respect for the needs of young children to learn through play; and fewer children per teacher. In addition to licensing child care operators, ODE and ODJFS certify programs with proven quality track records using the Step Up To Quality star rating system. Programs earn from one to five stars based on factors cited above, which are consistent with National Association for the Education of Young Children guidelines.[4] While it bears note that some quality markers are not formally measured, such as cultural competency, the Step Up To Quality program provides a good general indicator of program quality. Ratings and participation levels show that program quality varies widely in Cincinnati.

A note about data

This report relies on licensing inspection reports by the Ohio Department of Job and Family services, which oversees private childcare centers. The data are rich in detail, but change quickly as enrollment shifts and programs move into and out of the Step-Up-To Quality Program. The Ohio Department of Education similarly monitors public preschools but does not compile its reports into a central database. Requests for detailed records were not answered. For this reason, this report provides a more detailed picture of the private preschool landscape. What is known about public preschools is that they have some of the highest quality standards, including degreed staff and small classroom sizes, and that they are in high demand by Cincinnati families who have experienced wait lists to enroll their children.

Cincinnati Public Schools

Cincinnati public schools currently house 80 preschool classrooms in 37 schools. There are too few slots for all families who seek them. Some 1,700 families attempted to enroll their children last year for just 1,200 slots – the rest were wait listed. In response, CPS has announced plans to open ten more classrooms. Based on a review of the CPS website, new space does not appear open for the 2016-2017 school year.

Cincinnati Public Schools preschools appear to be in high demand because they are high quality. District preschools have teachers with Bachelor’s degrees in early childhood education, and commit to class sizes of ten students per teacher. These programs provide families the added advantage that enrollees are guaranteed admission to kindergarten at the school they attend. With some preschools housed at strong magnet schools, parents seek to enroll their children early. While aid is available to some, those who can pay full tuition may be at an advantage. Head Start is limited to families earning less than the poverty level ($24,250 for a family of four in 2015). On CPS’s scale, private tuition runs $6,800 for full-day and $3,500 for half-day preschool.

By providing supplemental funding, the Preschool Promise initiative would help families who can’t afford public preschool’s high tuition, and could reduce costs for families whose children are currently enrolled. Growing and better funding school-based preschools, which provide some of the city’s top quality preschool experiences, would vastly improve Cincinnati’s early learning landscape.

Centers

Childcare licensing inspection reports from ODJFS let us closely examine features of Cincinnati preschool programs at private childcare centers. In 2014 and 2015 inspection reports, Cincinnati preschools and childcare centers reported serving 4,269 children. About two thirds of these children, 2,845, participated in full-time childcare with some preschool programming, while another 1,424 participated in part-time preschool programs.

Center-based preschool costs may be prohibitive for families. Public funding is available to families as a work support, and those who qualify pay a fixed copayment based on income. However, since eligibility is contingent on the parent’s job, children may have to leave school if a parent is laid off. The income eligibility structure also presents challenges. Initial eligibility is limited to families earning up to 130 percent of the poverty level. While continuing eligibility grows to 300 percent, if a parent earns a raise and later loses a job, the family may lose eligibility even when she starts a new job, unless she takes a pay cut.[5][6] For Cincinnati, Issue 44 can bridge the gap. Ohio needs to align the public preschool and child care center funding models so that families across the state don’t fall into this trap.

The state funding formula also raises concerns. The ODJFS commissions a survey of centers every two years to determine the costs for self-pay families. The results provide a benchmark to price state reimbursements for childcare subsidies. Early education advocates recommend that the reimbursement be pegged to the 75th percentile market rate, the point at which 75 percent of programs cost less, and 25 percent cost more. That level is $910 per month in Cincinnati as of the latest report.[7] The state uses its benchmark as a ceiling, so less costly centers are reimbursed only for the rate they charge to families. The costliest programs would have to accept a discounted rate or forego subsidized children. While 23 states reimbursed at the 75th percentile in 2001, rates have been falling throughout the nation as levels fail to keep pace with the rising cost of care. Just one state, South Dakota, continues to reimburse at the 75th percentile. Ohio’s rate last year had fallen to the 26th percentile and was still chained to the market rate from 2008.[8] One of the primary goals of Preschool Promise is to provide adequate funding to make all the best programs affordable to the families who need them.

The state funding formula also raises concerns. The ODJFS commissions a survey of centers every two years to determine the costs for self-pay families. The results provide a benchmark to price state reimbursements for childcare subsidies. Early education advocates recommend that the reimbursement be pegged to the 75th percentile market rate, the point at which 75 percent of programs cost less, and 25 percent cost more. That level is $910 per month in Cincinnati as of the latest report.[7] The state uses its benchmark as a ceiling, so less costly centers are reimbursed only for the rate they charge to families. The costliest programs would have to accept a discounted rate or forego subsidized children. While 23 states reimbursed at the 75th percentile in 2001, rates have been falling throughout the nation as levels fail to keep pace with the rising cost of care. Just one state, South Dakota, continues to reimburse at the 75th percentile. Ohio’s rate last year had fallen to the 26th percentile and was still chained to the market rate from 2008.[8] One of the primary goals of Preschool Promise is to provide adequate funding to make all the best programs affordable to the families who need them.

Quality

The ODJFS rated 44 of Cincinnati’s 120 programs as participants of the Step Up To Quality program. Most programs have not yet been rated. Among programs that participated, the largest share had earned one star, in part because stars are cumulative as explained below, and 25 had earned a rating of three or more – the benchmark the state regards as a high quality rating. A 3-star program uses a developmentally appropriate curriculum, has staff with a combination of education and training in early childhood development, and implements a child-centered learning approach. Figure 1 shows the break-down.

The Step Up To Quality program is cumulative and was voluntary when these data were collected for the 2014-2015 school year. The program became mandatory for all public school-based preschools in July 2016 and will be mandatory for center-based preschools receiving public dollars in July 2020. Since participation has been voluntary up to now, programs that have an SUTQ rating have shown a commitment to quality by opting in. Because ratings are cumulative, programs must first apply for and earn one star before they can earn a second and so forth. This means that while a five-star program is definitely high quality, a one- or two-star program that is new to SUTQ may be very good as well.

One reason relatively few programs are participating in Step Up To Quality may be funding constraints. Delivering a top quality program means costly investments, especially in hiring educated staff, and keeping child/staff ratios low. Deeper public investments are needed to ensure programs have the resources they need to deliver quality early education to families in Cincinnati and the state.

Ensuring that staff are fairly and adequately compensated is key to delivering the best possible programs. An assessment below documents the low pay preschool teachers face, especially in private programs, and shows how Cincinnati can invest in early childhood professionals, who are the single biggest factor in delivering a quality program.

Besides rating centers on quality learning opportunities, ODJFS inspects all childcare centers to ensure compliance with state laws governing child health and safety. Three of 120 centers inspected had serious non-compliance violations. Such violations present substantial safety risks to children and are grounds for license revocation. None of the three centers in violation participated in Step Up To Quality. Among 114 remaining centers with inspection reports, 17 centers, just 15 percent, were fully compliant in their most recent license inspection.[9] Another 54 centers (49 percent) had lesser compliance violations, which had been remedied upon follow-up inspection, and 40 centers, (35 percent) had violations left unaddressed by the time of the follow-up. Licensing inspection reports, available on the ODJFS website, can be a useful way for parents to choose a program.

Advocates also flag in-home childcares as important providers, especially for families with non-traditional work hours. In-home programs, of which Cincinnati has more than 600, are not detailed here, due to their number, diffusion, small size, and limited data. The state just created a pathway for such programs to rank as SUTQ providers in 2014. Quality appears to vary widely, but efforts including a collaboration between Cincinnati 4C and the United Way are working to bring in-home childcare providers into the high quality sphere.

The access/quality trade-off

Research has often found that the most accessible programs are not always the highest quality. This seems to hold true for Cincinnati. Factors that affect access include school capacity, cost, schedules, and location. In Cincinnati, limited slots for public preschools have barred access to hundreds of children. While private preschools as a whole could serve all children, the best center-based preschools often have wait lists. The next biggest challenge is cost. Limited hours favor two-parent, flexible households. Low-income families often lack adequate transportation, which leaves some families in what some call access deserts. And limited wrap-around services mean that parents’ work schedules may bar them from a top quality program.

Quality deserts in poor neighborhoods

Cincinnati Public Schools wait-listed some 500 preschool children last school year. Many quality private preschools have wait lists too. Classrooms must be expanded through public investment. Below we discuss ways to serve more children with existing infrastructure. Doing so means both deeper resource investments, and efforts to bring existing programs – most of which have yet to attain high quality ratings if three or more stars - into the quality landscape.

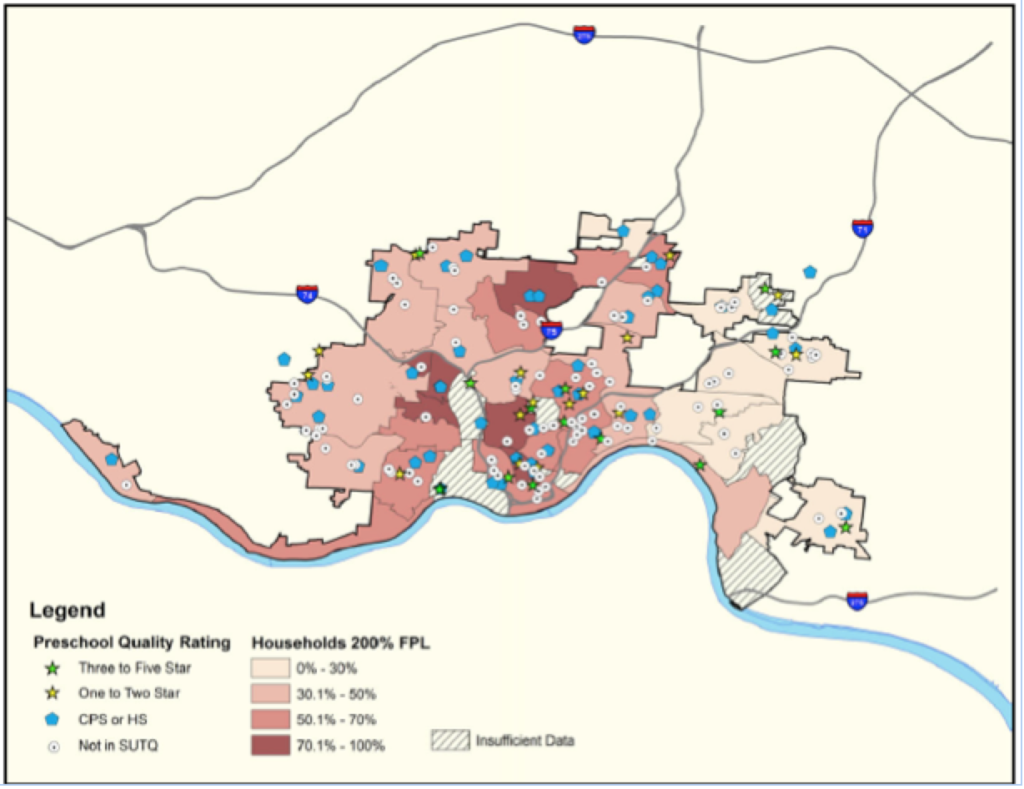

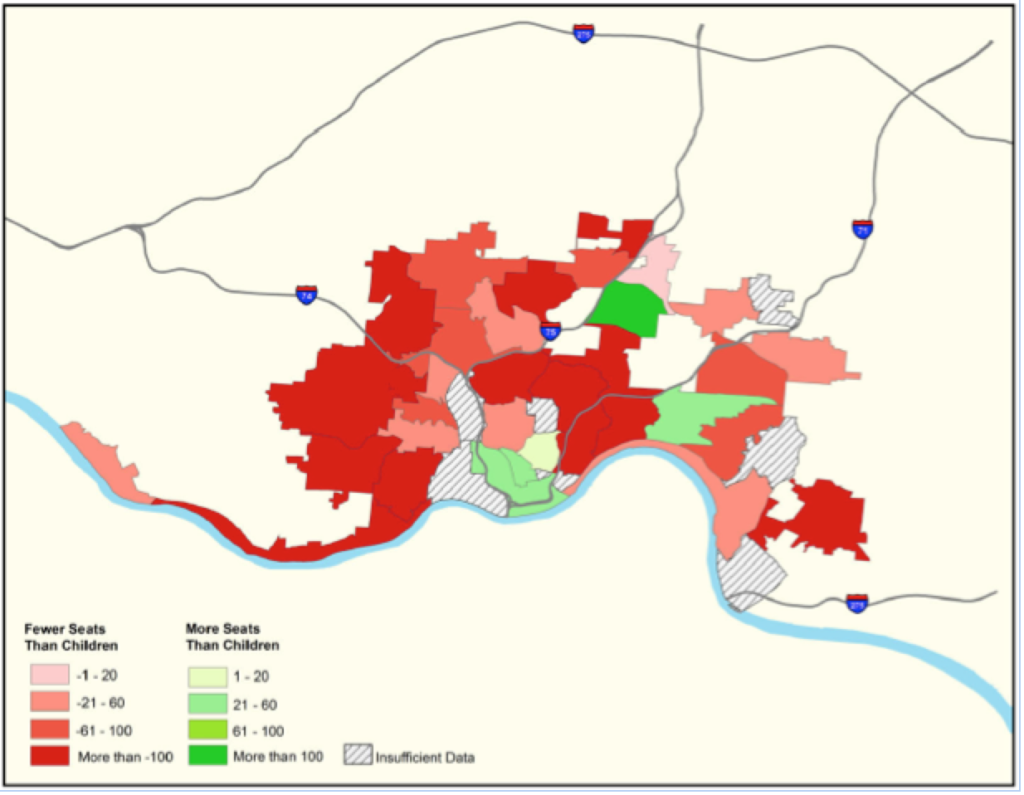

A report released by RAND this summer found that shortages of slots in high quality, 3+ star, programs were clustered by neighborhood, and that poor neighborhoods are highly likely to face shortages.[10] Policy Matters Ohio sorted programs by quality rating and zip code, and like RAND, finds that quality deserts are most pronounced in western Cincinnati neighborhoods. Maps reproduced here from RAND’s report illustrate the overlap between quality early childhood education deserts, and family financial hardship. While not all high poverty areas are equally isolated, neighborhoods experiencing greatest need include Price Hill, Lower Price Hill, Mount Airy, Westwood, South Cumminsville, Camp Washington, and Millvale. Subtracting the number of seats available to serve children in high quality programs from the total number of children reveals shortages in some communities exceeding 100 slots. Efforts are needed to bring programs to these communities, which are also geographically isolated from infrastructure like public transit that could help bridge shortfalls.

Reproduced from Lynn A . Karoly, Anamarie Auger, Courtney Ann Kase, Robert C. McDaniel, Eric W. Rademacher “Options for Investing in Access to High Quality Preschool in Cincinnati.” Figures 2.3 and 2.5.

Opportunities to grow

Providing the highest quality preschool experience for children in Cincinnati and the state means making deep public investments to ensure access for all. Building on the K-12 model for infrastructure, quality standards, and non-means tested funding should be a long-term goal. Yet already today, existing public and private programs could be tapped to provide universal preschool to all Cincinnati children starting at age four – and for those 3-year-olds in greatest need. Issue 44 is designed to bridge the gap between available state and federal resources already in place

Policy Matters Ohio found that demand for public preschools substantially exceeds available space. Offerings should be expanded. Combining public and private centers, Cincinnati has enough total programs that seats could be expanded to all area preschoolers using existing infrastructure, but a key challenge that remains is neighborhood-specific access deserts, especially in western neighborhoods, including pockets where between 30 and 50 percent of families are low income, earning less than double the poverty level.

Last year in Cincinnati, 114 centers served a reported 4,269 preschool-aged children.[11] Between them, there is current capacity for as many as 3,025 more full-time children and an unknown number of part-time children, without any changes to existing licensure. Centers have unused building capacity for 12,713 children and staff, meaning that with new staffing commitments, existing programs could be expanded to serve the entire preschool-age population of Cincinnati without building new facilities.

Cost to families

Policy Matters Ohio found that the biggest indicator of cost was not program quality, but operating hours. This makes sense, considering the labor intensive nature of preschool and childcare. Some preschools charge less than $200 per month, but programs at this price point are part-time, a few days per week, and therefore accessible only to families who have a stay-at-home parent or part-time work schedule that matches the program’s hours.

Programs with wraparound childcare, on the other hand, come with substantial price tags. The median cost of center-based preschool in Cincinnati is $781 per month. The 10th percentile program costs $569 a month. Programs in our survey ranged to $1,005 per month. Public school programs charge $6,800 for the year, and this cost is compounded by the need for parents to find other arrangements for holidays, including the summer.

Childcare and early education affordability is a major challenge for the typical Cincinnati family. The median household income for Cincinnati was $34,002 for the 2010-2014 period (including households with and without children). At a median cost of $9,372 per year, center-based preschool for a single child would eat up 27.6 percent of this typical family’s income. Ohio’s funding formula means a family in this situation might not receive any public dollars at all to defray the cost. This income puts a family of three at just 172 percent of the poverty level, but to meet initial eligibility standards for childcare funding, they would have had to apply while earning 130 percent or less.

Costs may be a burden even for those families fortunate enough to get help. Last year, Ohio eliminated childcare copays for families earning up to 100 percent of the official poverty level. That’s a step in the right direction. The state should consider raising that level. A report by the National Women’s Law Center found that an Ohio family earning 150 percent of poverty – if they qualify, by having received an initial subsidy when they were earning less – is still making a co-pay of $216 per month, 9 percent of the family’s budget.[12]

While the high cost of childcare means that affordability is a challenge not only for those struggling with poverty, Cincinnati is characterized by glaring income segregation and some neighborhoods have staggering incidence of families living below the official poverty line. Nearly one in three Cincinnatians is in poverty. Official poverty rates range from just 6 percent in some zip code, half the national average, to as high as 63 percent in others.

Families break even when preschool is free

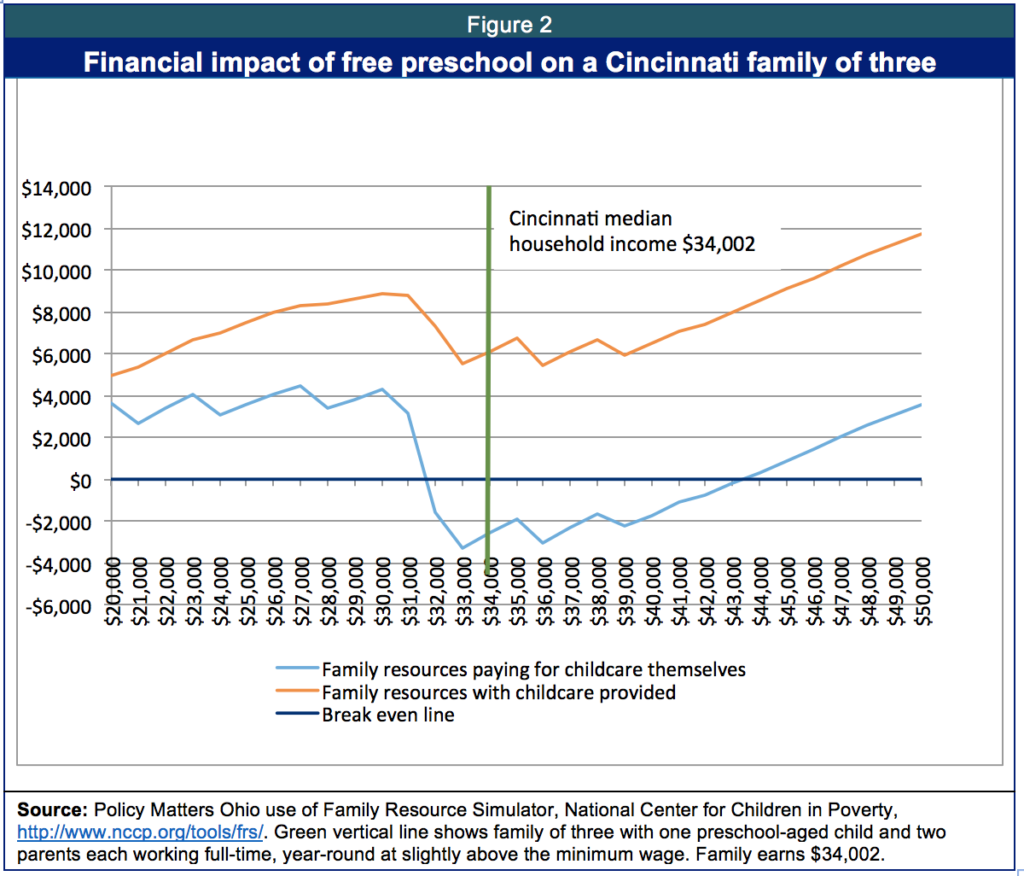

Policy Matters modeled how making preschool free would affect Cincinnati families at various income levels. We take a hypothetical family of three, with two parents employed full time outside the home. Note that under these assumptions, Cincinnati’s median household income is just slightly higher than Ohio’s current minimum wage of $8.10.[13]

Figure 2 shows how much the family has left over for the year once all expenses have been paid. We use modest assumptions that the family has no debt and contributes nothing to savings, so all income goes to meet current expenses. Note too that these expenses account for just one child. The income range appears on the horizontal axis at the bottom. The vertical axis column shows the family’s financial situation after expenses. The break-even line is at zero dollars. This chart shows that a family of this make-up earning between about $31,000 and $43,000 per year falls short. In order to break even, Cincinnati’s median family must either earn an additional $9,400 per year to rise into the $43,410 income bracket, or drop below $31,010, when food aid (SNAP benefits) phase in.

Considering the median earning household, a full tuition waiver would raise the family to solvency. Their after-expenses resources would rise from a shortage of $2,585 to a savings of $6,116. Free preschool with wraparound childcare would serve as a work support to enable both parents to work. Preschool Promise can help fill this gap, but larger scale policy changes to childcare funding are needed. This family would not be initially eligible for childcare assistance based on an income of just 172 percent of the poverty level. Restoring initial eligibility from its current level of just 130 percent of the federal poverty level to 200 percent would enable a family of three earning up to $40,180 to access affordable childcare and preschool. As this chart shows, families at that earnings level still need the boost.

A high quality preschool means a high quality workplace

Allocating public resources for early care and education not only provides a crucial work support to families and allays unmanageable costs; it also ensures better outcomes for children by providing programs with the resources they need to deliver the highest quality. The most essential of these resources are teachers themselves.

Preschool teachers play a vital role in shaping the early development of the youngest Cincinnatians. Preschools also provide safe spaces for children, enabling parents to work. Yet this female-dominated profession of vital workers suffers from entrenched low pay that leaves teachers with too few resources to meet their own family needs. Private, center-based preschool teachers make less than 97 percent of all workers. As a result, terrible turnover rates characterize the landscape, especially in the private sector. This turnover disrupts classroom continuity and fractures key relationships young children form with their teachers. These relationships, when safeguarded, form the bedrock of stable early development. Providing quality early learning to help children grow depends on taking care of the teachers who care for them.

High quality early education programs are linked to immense improvements in children’s development that last into adulthood – particularly for poor children. For Cincinnati, a city which ranks third in the nation for child poverty at 48 percent, the stakes are high and the opportunities great.[14] Children who have participated in good preschools go further in school, are held back less, and require fewer special education services.[15] They grow into adults with higher earnings, more college education, better health, less likelihood of incarceration and lower need for public assistance. Studies across the nation have documented that, due to these outcomes, investments in high quality pre-k deliver civic and economic returns valued between $3 and $7 per dollar spent.[16] These outcomes hinge on the quality of care. Teacher job quality – especially livable wages – does more than any other factor to ensure high quality care.

The National Survey of Early Care and Education documents substantial links between program quality and teacher pay. Higher paying programs are able to hire teachers with more education, and better retain them as their experience grows. Teachers with a bachelor’s degree were paid 49 percent more than those with a high school diploma only. Head Start programs, where teachers made $17.90 on average in 2012, have some of the lowest turnover rates in the field, at 10 percent. By contrast, for-profit chains, where teachers made $12.20 an hour at the average, had 27 percent annual turnover.[17] High turnover disrupts forming the strong relationships with stable adults that children need, especially for children who face instability from poverty, frequent moves, housing and food insecurity, and parents living under the constant stress of these factors.

Preschool teachers earn less than other similarly educated workers – and the gap widens as education levels rise. That creates challenges to hiring and retaining highly qualified teachers. High school graduates in early childhood education earned 28 percent less than their peers, but preschool teachers with a bachelor’s degree earned 45 percent less than degreed workers in other fields.[18] Implementing living wages for teachers is not only a way to invest in quality pre-k, doing so also improves wage equity since preschool teachers are overwhelmingly female.

In Worthy Work, STILL Unlivable Wages, researchers at UC Berkeley identify the Department of Defense childcare program for military families as a model for providing high-quality programming with good teacher pay at rates families can afford. Preschool teachers earn between $28,262 and $45,512 for non-management roles.[19] The program requires staff to hold an early childhood education degree or demonstrate its equivalent through a combination of education and work experience. By supplementing existing funding streams and conditioning support on high quality standards, the Preschool Promise initiative could make that successful model a reality for all Cincinnati families with young children.

Preschool teachers among the lowest earners

Unfortunately, preschool and childcare settings like those provided for service members are not the norm. Preschools in the United States and in Cincinnati are not doing enough for teachers. Nationwide, childcare teachers earn less than 97 percent of all workers. Cincinnati center-based teachers earn even less than that: $20,310, compared to national average earnings of $21,490.[20] Public preschool teachers fare slightly better, but still earn less than 81 percent of workers. Nationally, public preschool teachers earn $31,420, about 46 percent more than in private centers.

Women comprise 96 percent of preschool and childcare teachers nationally. African Americans are over-represented in the field at 16 percent of preschool teachers nationwide, and 13 percent of the population.[21] This means that raising early childhood teacher pay is a step toward race and gender pay equity.

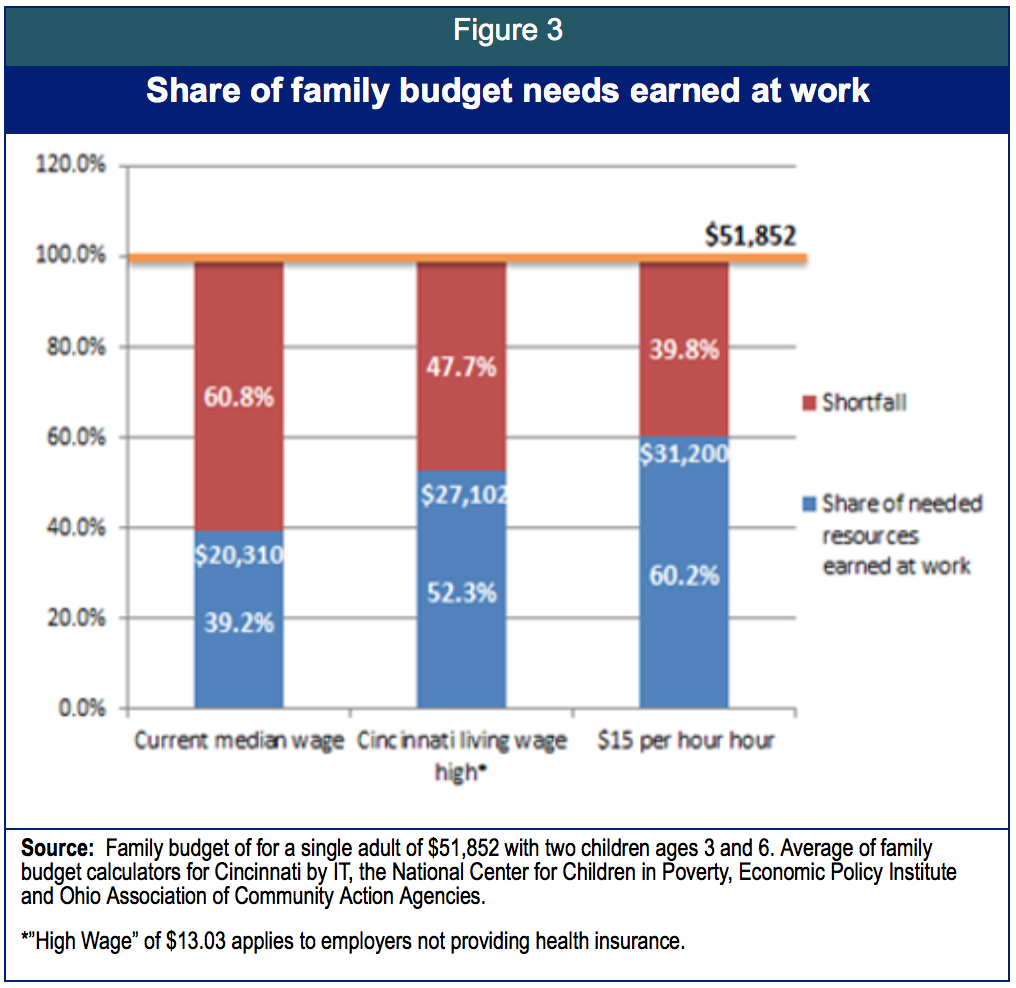

In Cincinnati, the average private center-based preschool teacher is earning just $20,310 per year, the equivalent of $9.76 an hour for full time work. Based on an average of four cost-of-living indices, that’s about 61 percent below the subsistence level for an adult with a preschooler and first grader; such a family would need around $51,852 in Cincinnati.[22] [23] Figure 1 shows the shortfall in the median private preschool teacher’s earnings for a teacher with this hypothetical family. While this family may have access to other resources, such as food aid, or child support payments from a noncustodial parent, it is clear that pay from this full-time job would not be enough to meet immediate basic needs, let alone pay off debt or begin saving. At current wages, this working mother (since 96 percent of early childhood education workers are women) is making less than half her family’s needs. That means that even with a partner contributing the same earnings as she is, the family is in the red.

Preschool teachers’ pay is not just tight, it’s unsustainable. Nationwide, 46 percent of childcare-based teachers are using public assistance.[24] Nearly half of teachers from an independent study report fears of having too little food for their families.[25] In a sad irony, preschool teachers often earn too little to enroll their own children in pre-k: in Cincinnati, the median cost of preschool, $9,372, is 46 percent of the pre-tax earnings of the average private preschool teacher.[26]

Cincinnati can deliver for teachers

By providing additional funding to centers, Cincinnati could create a wage floor for preschool teachers to help remedy this shortfall and bring private center preschool teacher salaries in line with those of public school districts. Cincinnati has set a precedent for this by creating a Living Wage Index for city contractors. That measure is a good start, but the $13.03 now in force for workers not receiving employer health coverage still falls short of both alignment with public programs, and cost of living.[27] A worker at this wage would earn $27,102 per year for full time work, and could afford just 53 percent of her family’s needs. A stronger minimum wage benchmark for preschool teachers would be $15 per hour, which would place full-time workers at a $31,200 annual wage, covering 69 percent of family budget needs.

Because public programs pay higher wages and earn stronger quality assessments, delivering city-wide preschool through a public system is likely to yield the most positive outcomes and create the greatest benefit to the community. Professional credentials and recognition for staff are vital to a quality program. With a conclusive body of evidence showing the benefits of early education, it is time to take steps toward implementing large-scale pre-k, especially pre-k that includes robust public offerings accessible to all families where they live.

Hours of care

Policy Matters examined access to preschool based on hours of availability. There is a trade-off between quality and operating hours with the best-rated programs offering more limited hours and less inclusion of wraparound care. This restricts access to families who have a parent or babysitter on stand-by to drop off and pick up the child. Limited wrap-around services are one of the key barriers families face to accessing high quality public preschools.

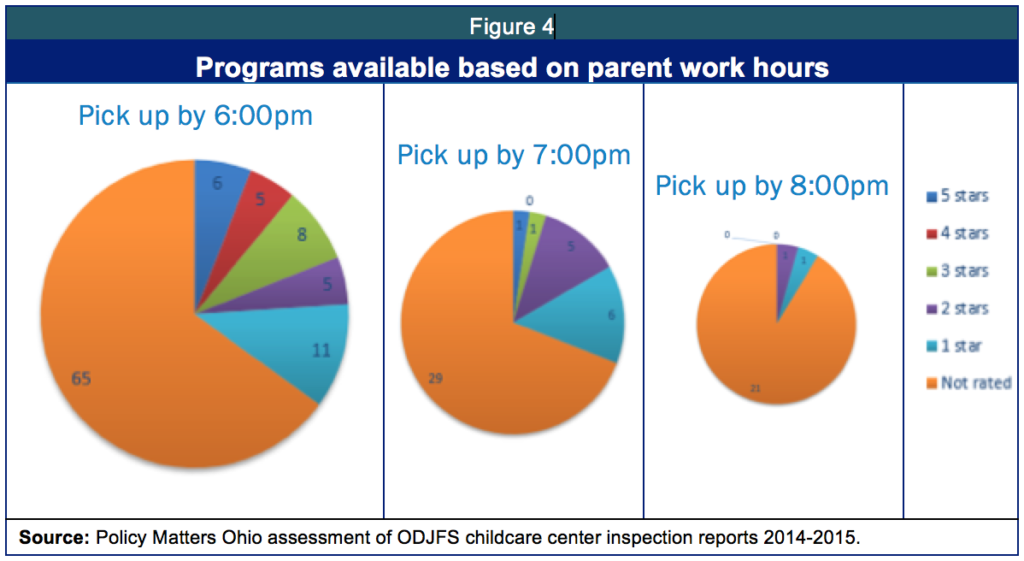

Public preschools are open on a limited basis during school hours, ending in the early afternoon before most parents leave work. As for private centers, figure 2 shows the share of programs available to families based on their work schedules. The vast majority of programs, regardless of hours, are unrated. Among rated programs, less than half have received a rating of four or five.

Families with traditional hours have both more overall options and more quality options. A family in which at least one parent works a traditional 9-5 schedule and can pick up a child by 6:00 p.m. can use at least 100 centers. Thirty-five of these are star-rated and 19 are rated 3-star or higher. But a parent who needs just one more hour for pick-up can choose from only 38 centers, nine of them star-rated, and two rated at three or more stars. This is a barrier for families working only slightly atypical hours. For parents on nontraditional or erratic schedules, the challenge mounts quickly. Just two star-rated programs are open past 7:00 pm, and only two programs, not rated, are open after midnight.

A key priority must be ensuring access to high quality preschools for all families. To achieve this, programs need to provide wraparound childcare. Currently in Cincinnati, the highest-rated programs on average offer less flexible scheduling than unrated programs and those with only one or two stars.

The average unrated center was open 12.1 hours a day, while the average center with a 5-star rating was open just 9.6 hours. No program with a star rating above two was open more than twelve hours, whereas 38 unrated programs were open twelve hours or more, and twenty were open at least 16 hours. The latest pick-up time for a three-to-five star program was 6:30 p.m., and 24 of 25 of these programs closed by 6:00. Among unrated programs, nineteen were open until at least 11:00 p.m., and two were open 24 hours. There are important differences between childcare and pre-k, and children are not attending pre-k during evening hours, but attaching wraparound childcare to pre-k can make the difference in allowing families to participate. It is the childcare component of these programs that enable them to function as a vital work support.

This trend shows a stratified market for preschool that locks some families out of high quality programs. Families with a stay-at-home parent, or in which both parents work the 9-5 schedule typical of office workers, have access to high-quality programs. Parents who work nontraditional hours have severely limited access. The children of these parents, who often earn low wages, have a real need for a high-quality program. To fully address the needs of working families, more and better programs need to offer care during nontraditional work hours.

A key opportunity to fill this gap may be found in partnerships between public preschools and private childcare centers or home based caregivers. Coupling a high-quality district preschool with a good extended-hours childcare center connects the child to a highly skilled early learning staff to prepare her for the academic learning she will soon take on, and shifts the focus of the childcare provider to delivering a safe and nurturing space for the child whose parent is still at work at the end of the school day.

Policy Recommendations

- Pass Issue 44 to both increase resources for K-12 and undertake a broad initiative to build out quality preschool in Cincinnati

- Restore initial eligibility for publicly-funded childcare to 200 percent of poverty level.

- Boost reimbursement rates to the 75th percentile so that families can choose from an array of programs, including top rated programs.

- Increase participation in quality ratings programs. Making SUTQ mandatory is a step in the right direction. Delivering the resources programs need is the next step.

- Increase preschool offerings in public schools where quality is high and demand far exceeds capacity

- Explore partnerships between public preschools and good extended hours childcare centers and home providers to provide the best pre-academic learning and wraparound care. Rate in-home providers using SUTQ.

- Invest in teachers. Substantially increase teacher pay to attract high quality staff with strong credentials, and keep them focused on their work.

The tension between access and quality leaves communities grappling between shoring up good programs that some families are locked out of, and expanding access to all families to some program, but leaving many children to cope with poor quality. Yet the studies are conclusive: positive developmental and academic outcomes depend on access not only to some preschool program, but to a good one. The trade-off between access and quality is a false choice. Bridging the gap for Cincinnati’s early learners depends fundamentally on dedicating adequate funding to achieve both.

By expanding access to high quality programs to all families, Cincinnati can not only improve early learning outcomes for children, but also secure financial stability and enhanced workforce access for Cincinnati families. Both are vital to delivering on the promise of a bright future for Cincinnati children.

[1] This report identifies an estimated 10,000 preschool children, including five-year-olds not yet in Kindergarten, using figures from the 2010 Census. A report by Rand on the same initiative earlier identified some 9,150 preschoolers using ACS 5-year estimates from 2010-2014.

[2] The 2010 Census recorded 21,846 children under age five in Cincinnati. Assuming they are evenly distributed across ages, there were an estimated 8,738 three- and four-year-olds in the city. Policy Matters estimates there were some 1,336 five-year-old preschoolers on a typical school day. The share of 5-year-old preschoolers grows over the school year as more children reach their fifth birthday. Policy Matters estimates their number as an average of all such children across school days. Figures also assume a 6 percent “red shirting” rate (when parents hold a five-year-old back from kindergarten to give the child time to mature), consistent with National Center for Education Statistics findings for the 2010-2011 school year.

[3] Those already in kindergarten are classified as School Agers, and children can be classified as School Agers beginning the summer before they enter kindergarten, even if they are only four years old. Three-year-old preschoolers are mandated smaller class sizes of twelve per teacher, while older preschoolers can be taught in classes of fourteen to one.

[4] Starting in July 2016 for state preschools, and July 2020 for centers, all Early Childhood programs receiving public funding will be required to participate in Step Up To Quality. The program will remain optional for privately funded programs, http://www.earlychildhoodohio.org/files/sutq/StandardsOverview5_2015.pdf.

[5] http://codes.ohio.gov/oac/5101%3A2-16

[6] Patton, Wendy, “Ohio’s childcare cliffs, canyons and cracks,” Policy Matters Ohio, May 2014, http://www.policymattersohio.org/childcare-may2014

[7] The Ohio State University Statistical Consulting Service, 2014 Ohio Child Care Market Rate Survey Table 41, p. 57, weekly rate for Full time preschoolers, cluster D https://jfs.ohio.gov/cdc/docs/MarketRateSurvey2014.stm.

[8] National Women’s Law Center, Building Blocks: State Childcare Assistance Policies 2015, Table 4A, State reimbursement rates in 2015, p. 31, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/CC_RP_Building_Blocks_Assistance_Policies_2015.pdf.

[9] Three Cincinnati centers are start-ups not yet in operation as of these inspections.

[10] Lynn A . Karoly, Anamarie Auger, Courtney Ann Kase, Robert C. McDaniel,

Eric W. Rademacher, Options for Investing in Access to High-Quality Preschool in Cincinnati, RAND, 2016.

[11] Among 120 centers, three were start-ups not yet open at the time of their latest reported inspection. Three others were cited with serious noncompliance violations – conditions that pose substantial risk of harm to children and are grounds for loss of operating license. Both were removed from consideration, leaving 114 programs examined here.

[12] National Women’s Law Center, Building Blocks: State Childcare Assistance Policies 2015, Table 3a: Parent Copayments for a Family of Three with an Income at 150 Percent of Poverty and One Child in Care, p. 28, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/CC_RP_Building_Blocks_Assistance_Policies_2015.pdf.

[13] $34,002 divided by 2,080 hours for each of two earners is $8.17 per hour. This exceeds both the 2014 minimum wage during which this figure was taken of $7.95 per hour, and the current state minimum wage of $8.10. Ohio’s minimum wage did not rise in 2016.

[14] http://www.cincinnati-oh.gov/simpson/youth-commission-of-cincinnati/news/councilmember-simpson-to-present-at-mayerson-student-workshop/

[15] Whitebrook, Marcy, Deborah Phillips and Carollee Howes, Worthy work, STILL Unlivable Wages: The Early Childhood Workforce 25 Years after the National Child Care Staffing Survey. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, 2014, p.. 8.

[16]Whitebrook, Phillips and Howes, p 8

[17] Public school-based preschools where teachers made $25.30 an hour had moderate turnover of 14 percent. This may be explained by teachers moving within their districts to higher grades.

[18] Gould, Elise. “Child care workers aren’t paid enough to make ends meet.” Economic Policy Institute, November 5, 2015, http://www.epi.org/publication/child-care-workers-arent-paid-enough-to-make-ends-meet/

[19] General Schedule qualifications https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/classification-qualifications/general-schedule-qualification-standards/1700/general-education-and-training-series-1701/ and wage table https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/pay-leave/salaries-wages/salary-tables/pdf/2016/GS.pdf.

[20] National average earnings for childcare teachers were $21,710 in 2013, http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes399011.htm; compared to $20,310 for Cincinnati in 2014.

[21] American Community Survey, from http://www.irle.berkeley.edu/cscce/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/ReportFINAL.pdf p. 61

[22] This figure is taken from an average of MIT’s living wage calculator: $50,586, the Basic Needs Budget Calculator by Columbia University’s National Center for Children in Poverty: $52,581, the Economic Policy Institute’s Family Budget Calculator: $53,616, and the Self-Sufficiency Calculator by Ohio Association of Community Action Agencies: $50,627.

[23] We model a single parent household to isolate the subsistence wage for one worker. This model reflects the reality for 52.3% of Cincinnati families with children http://www.cincinnati-oh.gov/simpson/youth-commission-of-cincinnati/news/councilmember-simpson-to-present-at-mayerson-student-workshop/ .

[24] Jacobs, Ken; Ian Perry and Jenifer MacGilvery. The High Public Cost of Low Wages, UC Berkeley Labor Center, http://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/the-high-public-cost-of-low-wages/

[25] Whitebrook, Phillips and Howes, p 45.

[26] Ohio Child Care Market Rate Survey, https://jfs.ohio.gov/cdc/docs/MarketRateSurvey2014.stm, p. 55.

[27] Employers providing health insurance are allowed to pay even less: just $11.54 per hour.

Tags

2016Early Childhood EducationMichael ShieldsPhoto Gallery

1 of 22