Boosting home care options under Medicaid: Balancing Incentive Payment Program, Community First Choice Option

January 29, 2013

Boosting home care options under Medicaid: Balancing Incentive Payment Program, Community First Choice Option

January 29, 2013

Press releaseThe state is already improving services and controlling costs by reducing complexity, and creating a managed care pilot. But more can be done to help people in their homes, bring additional federal dollars to underwrite these services, and create jobs in the community.

Download the full report

Executive summary

One of the many ways that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) curbs  the cost of health care is by offering incentives to states to provide services in the most cost effective way possible: at home or in the community. These incentive dollars can boost health care spending in neighborhoods, creating new jobs as well as expanding needed services.

the cost of health care is by offering incentives to states to provide services in the most cost effective way possible: at home or in the community. These incentive dollars can boost health care spending in neighborhoods, creating new jobs as well as expanding needed services.

In Ohio and nationally, a significant share of Medicaid is dedicated to patients who are elderly or have disabilities. Too often, this is in a high-cost nursing home setting. The ACA offers incentives to encourage more cost-effective home care services for people who need help with dressing, bathing, chores, preparing meals, or other activities of daily living. A study of state expenditures on long-term care and services between 1995 and 2005 found that states with broad access to home and community-based services realized cost savings in the long term as they shifted from institutionalized settings (nursing homes) to home care services, although there was a short-term increase in costs during the shift.[1]

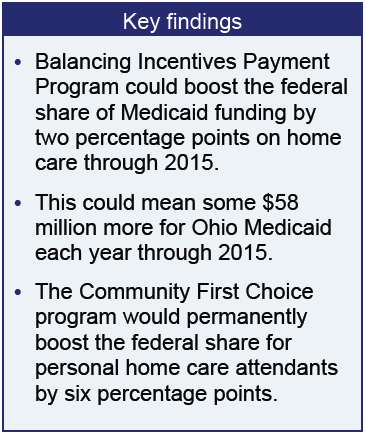

The ACA offers new opportunities to help states provide long-term services and supports to people in their homes. This brief examines two of the programs: The Balancing Incentives Payment Program, which increases federal matching funds for states like Ohio by two percentage points through 2015 for increased home and community-based services, helping with any up-front costs, and the permanent Community First Choice Option (CFCO) which provides a boost of six percentage points, from 63.58 to 69.58 percent, in federal funding for personal attendant services in the home or community.

One estimate finds Ohio could gain $58 million a year from the Balancing Incentives Payment Program.[2] The Unified Long Term Care System Advisory group recommended authorization be included in the current state budget,[3] and it was, but the application has not been submitted. The

Community First Choice option could bring a permanent six percentage point increase in federal Medicaid match for selected services. California received $573 million over two years for its Community First Choice option.[4] New York anticipates $90 million annually.[5] Alaska, with its small population, expected about $11.8 million over two years.[6] While California is the only state approved for the CFC at present, others – Arkansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, Montana, New York and Oregon – have announced plans to apply, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.[7]

Medicaid services for those in need of long-term care

Medicaid serves 56 million recipients, more than any other health program. Enacted in 1964 under Title XIX of the Social Security Act, Medicaid provides medical services to people with disabilities or low incomes, and it is an important source of aid for elderly nursing homes residents.[8] In Ohio, it serves 2.3 million low-income children, their parents if the family is very low-income, and those who are elderly, blind or have disabilities. Non-elderly adults without disabilities or without children are not eligible. Financial need, based around federal poverty levels, is used to determine eligibility. Medicaid is jointly financed by the federal government and the states, with Washington paying 50 percent of the costs in higher-income states and about 70 percent in lower-income states like Arkansas.[9] In 2013, the federal match in Ohio is 63.58 percent.[10]

States define eligibility and benefits within guidelines set by federal law. The only two mandated benefits for long-term care under the Medicaid program are institutional care and home health services for those not eligible for nursing home (institutional) care.

Since 1981, states have used authority under Section 1915(c) of the Social Security Act to request a waiver of certain federal Medicaid requirements (including state-wide program coverage) to establish home and community-based programs to serve people who need institutional levels of care. States have broad authority to seek approval to provide a wide range of services under waivers.

The Community First Choice Option funds personal care attendants. Since 1975 states have had the option of offering personal care services as part of the statewide Medicaid plan as well as through waivers, which may be limited geographically or in other ways. States have considerable discretion in defining personal care but programs typically involve non-medical assistance with daily living (e.g., bathing and eating) for participants with disabilities and chronic conditions.

The section below describes Ohio’s system of home and community-based care for low- and moderate-income people who need significant assistance in health care and daily living, and the comprehensive changes underway to streamline and simplify the system and rebalance institutional care with care in the home and community.

Ohio’s existing system

Since Medicaid was established in 1965, states have been required to cover nursing facility care for beneficiaries age 21 and older who need help with daily living (dressing, bathing, feeding, or mobility). As noted above, federal law allows states to apply for a formal waiver of program rules to provide services outside of a nursing home. Over time, more services have been covered in community settings, and the federal government has created several different types of waivers for state programming.

In April of 2011, Ohio Medicaid Director John McCarthy described his program in budget testimony: “What is the Medicaid program and who does it serve? Medicaid is the health insurance program for low-income families with children; and the aged, blind, and disabled. …. The program covers children up to 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL), parents of those children to 90% FPL, and the elderly or individuals with disabilities up to 64% FPL, unless they meet an institutional level of care and then it is 150% FPL.”[11] In addition to those Director McCarthy described, individuals are eligible for waiver services if they have income less than 300 percent of the SSI standard of need and require an institutional level of care. For nursing home care, income can be higher as long as monthly income is less than the nursing home’s Medicaid reimbursement rate.

Ohio’s Office of Health Transformation points out that the state’s Medicaid program “serves approximately 173,000 individuals with long-term care needs – primarily seniors and people with disabilities – each year. Although only 7 percent of the Medicaid population uses long-term services and supports, approximately 41 percent of annual Medicaid expenditures stem from services to these individuals.”[12] This is a little higher than national averages. Nationally, 6 percent of the Medicaid population needed long-term services and supports in 2010[13] and about a third of Medicaid spending in 2010 was directed to these services.[14]

According to the Ohio Office of Health Transformation, in 2011 Ohio was spending more of its Medicaid budget on high-cost nursing homes and other institutions than all but five states, and Ohio taxpayers were spending 47 percent more for Medicaid long-term care than taxpayers in other states.[15] Ohio’s current budget rebalances where the money is spent by increasing allocations to home- and community-based services from 36 percent of Medicaid long-term care spending today to 42 percent in SFY 2013.”[16] The current budget bill sets an aspirational goal of a 50/50 balance (institutional v. community-based as measured by the number of participants) for Ohioans age 60 and above, and a 60/40 balance for Ohioans under age 60 with physical disabilities. Correcting the imbalance is important because nursing home care is expensive, with the average daily Medicaid rate for an Ohio nursing home now at $167 per day.[17] Home and community-based care costs less. For example, the National Health Policy Forum reported that in 2011, the average annual cost for nursing home care was more than $78,000; for assisted living communities, it was almost $42,000.[18]

Ohio has many waivers in place that provide home and community-based care. Ohio’s system for this care is comprised of nine waiver-based programs and one plan amendment. These programs are administered under the authority of three different state agencies: the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, the Ohio Department of Aging and the Department of Developmental Disabilities.

The Department of Aging administers three waiver programs: PASSPORT, Choices, and Assisted Living waivers. The department also oversees a small program provided as part of the Medicaid plan itself (PACE). Descriptive information here is taken from the website of the Ohio Department of Aging.

- PASSPORT (Pre-Admission Screening System Providing Options and Resources Today), is a waiver program that provides services in home and community settings to delay or prevent nursing facility placement for people 60 and older who need hands-on assistance with dressing, bathing, toileting, grooming, eating or mobility. Their care services must not exceed 60 percent of the cost of nursing home care. Clients must meet financial criteria for Medicaid eligibility and their physicians must agree to a service plan. PASSPORT is by far Ohio’s largest waiver for home- and community-based services for the elderly, with enrollment of 33,103 consumers in December of 2012.

- Choices waiver provides home and community-based services and supports to older Ohioans. Geographically limited, it is available to current PASSPORT consumers in the central Ohio, northwestern Ohio, and southern Ohio regions served by the Area Agencies on Aging based in Columbus, Toledo, Marietta and Rio Grande. It serves 559 people 60 and older, with a capacity to serve 1,610, and offers personal control over services.

- Assisted Living waiver serves people 21 and over who need hands-on assistance with dressing, bathing, toileting, grooming, eating or mobility; meet the financial criteria for Medicaid eligibility and are able to pay the state established monthly room and board payment (rent). It provides services in a community residential setting with around-the-clock personal care but not skilled nursing comparable to a nursing home. As of December 2012, there were 3,899 enrollees in the assisted living waiver.

- PACE (Program for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly), is a managed-care model that provides participants with all of their needed health care, medical care and ancillary services in acute, sub-acute, institutional and community settings. Like Choices, it is geographically limited, to sites in Cincinnati and Cleveland. It serves people over 55 years of age who are eligible for Medicaid (although the program accepts private-pay clients) and who need an institutional level of care. It served 780 people in December 2012. PACE is not a waiver program; rather, it is a part of the state Medicaid plan.

The Ohio Department of Job and Family Services administers three programs that serve those with disabilities who are eligible for institutional care, but prefer home care. Information here is taken from the website of the Ohio Office of Health Transformation and the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services.

- Ohio Home Care waiver for people with physical or developmental disability who are 59 and younger. It had 8,778 enrollees in June of 2012. It is designed to meet the needs of consumers eligible for Medicaid who have been assessed to require an intermediate or skilled level of care. Without the services available through the waiver benefit, these consumers are at risk for hospital or nursing home placement. Consumers approved for the OHC waiver benefit may receive care at home or in a nursing facility.

- Transitions waiver, for all ages with developmental or physical disabilities, had 2,931 participants in June of 2012. This benefit package consists of all of the services as listed above. However, it is designed to meet the needs of consumers eligible for Medicaid who have been assessed to require an ICFMR/DD (intermediate care facility for the mentally retarded/developmentally disabled) level of care. This waiver is not open to new enrollees. You must first be on the OHC waiver and be transitioned due to level-of-care considerations.

- Transitions waiver carve-out This benefit package consists of all of the services as listed above. However, it is designed to meet the needs of consumers who are age 60 and over. Eligibility criteria require having either an intermediate or skilled level of care. This waiver is not open to new enrollees. You must first be on the OHC waiver and be transitioned due to reaching age 60. There were 2,056 enrollees in June of 2012.

The Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities administers three waiver programs, described below. Information here is taken from the waiver handbooks at the website of the Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities, and from the website of the Ohio Office of Health Transformation.

- Individual Options (IO) waiver serves 16,787. The IO Waiver is for people with developmental disabilities who require the level of care provided in an Intermediate Care Facility for people but want to live at home or in the community and who meet the financial criteria of Medicaid eligibility.

- Level I waiver (LI) covers services for all ages and served 11,141 individuals as of June 2012. It serves people who require the care given in an Intermediate Care Facility for the Mentally Retarded but want to live at home. The cost for this help cannot be more than what the Level I Waiver allows.

- SELF waiver, a new program, has a goal of serving 2,000 over three years. At its one-year anniversary, as of December 10, 2012, there were 26 individuals enrolled on the SELF Waiver, 10 of whom are utilizing a state-funded Children with Intensive Behavioral Needs (CIBN) SELF Waiver.

The current budget bill, HB 153, established a goal of boosting the number of Ohioans served in their homes through these programs. Rebalancing institutional care with home and community based services is, however, is taking longer than originally anticipated.[19] There are two major initiatives underway to facilitate improvements. One will consolidate five of its nine waivers into a single, unified waiver system (PASSPORT, Choices, Assisted Living, Transitions and Transitions ‘carve out,’). Today, programs are accessed through different agencies and entities; in the future, the goal is to provide coordination through a single entry point (the “front door”) and a common website. [20]

In May 2012, Director McCarthy praised the unification effort. He pointed out that HB 153 made access and navigation of the system easier by authorizing a single waiver that will serve 46,000 adults with disabilities and people over the age of 65 who need a nursing home level of care and said program design had begun.[21] Another initiative, however, a geographically based managed care demonstration project, was prioritized and will go into effect September 1, 2013. [22] In his testimony Director McCarthy explained that the state delayed the unified waiver to reduce disruptions as the new demonstration project is implemented.[23]

While the system of home-based care is undergoing change, funding for these services could be augmented by the enhanced federal Medicaid match of the Balancing Incentives Payment Program and Community First Choice. As implementation is just now taking place, the requirements of these programs could be worked into the initiatives moving forward. The next section focuses closely on these two programs.

Balanced Incentive Payment Program

A temporary incentive program, the Balanced Incentive Payment Program (BIPP) provides enhanced federal matching payments (“FMAP”) to states to allow them to increase Medicaid payment for long-term care services to people in their homes.[24] States like Ohio that spend between 25 and 50 percent of their long-term care Medicaid dollars on home and community-based services may apply for an additional two percentage points in federal matching funds for many services in the home, including services provided under waivers.[25]

The law makes available up to $3 billion in federal matching funds during a limited period: October 1, 2011 thru September 30, 2015. To qualify for the BIPP, a state applies to the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) with an outline of plans for expanding Medicaid home and community-based care services and describing its approach to making the required administrative structural changes in its delivery system (outlined below). The plan must be implemented six months after the date of application.

What the state must do to get BIPP funding:

Within six months of applying for funding under the BIPP, the state must institute administrative changes to increase home and community service use in Medicaid, including:

- “No wrong door single entry point system” that will enable consumers to gain access to all services through a single point where they will receive information, referrals and an eligibility assessment. The “no wrong door” strategy is to include:

- A set of ‘entry’ agencies;

- A website and;

- A statewide 1-800 telephone number.

- "Conflict-free" case management to develop individual service plans and to arrange for and conduct ongoing monitoring of services (i.e., no conflict of interest regarding the case manager and the service providers).

- A core, standardized eligibility and service assessment.

- States must report on services, quality and outcomes.

- States must maintain 2009 eligibility levels for all non-institutional Medicaid services for which the states will get an added federal payment percentage (see below).

Ohio is moving toward meeting these requirements.[26] A PDF posted on the Ohio Department of Aging’s website recounts progress Ohio has made toward meeting the requirements of the BIPP:

Ohio is moving in the direction of significant system reform efforts consistent with the requirements of the BIPP.

- Front door work/development of Aging and Disability Network/Continued “Connect me Ohio” website development.

- Level of care criteria changes/single assessment tool.

- Transition program (ie, HOME choice).

- Streamlined Medicaid eligibility

Application for the program was approved in HB 153, the current state budget bill.[27] The governor has a goal of rebalancing institutional care 50/50 with home-based care, the same goal as the Balancing Incentive Payment Program. A spokesperson for the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services said that a BIPP application was considered, but delayed because of a desire for more analysis of the demonstration period. [28]

The state should maximize federal funding by moving the application forward, possibly in the upcoming state budget.

Community First Choice Option

The Affordable Care Act establishes the Community First Choice Option (CFCO) in Medicaid to encourage states to provide home and community-based personal attendant services on a statewide basis for people who require an institutional level of care. The announcement of the program from the federal Department of Health and Human Services touted the fact that states could get a six percentage point increase in federal matching funds and that over three years states could see a total of $3.7 billion in new funds for personal attendant services in the home.[29] This is a permanent program, not time limited, like the Balancing Incentives Payment Program. Generally speaking, federal funds pay 63.58 percent of the cost of mainstream Medicaid services in 2103. A six percentage point increase means the federal government would pay 69.58 percent of the specific services included under the Community First Choice option in 2013. (The federal match is allocated by formula and the baseline may change from year to year based on the federal formula.)

California, the first state approved for funding under the CFCO, looks forward to $573 million in new federal funds.[30] New York expects $90 million annually.[31]Alaska, one of the least populous states, anticipates $11 million over two years;[32] this seems small but the program is permanent, so over 10 years, the additional funding would be $55 million.

The Community First Choice Option serves seniors as well as those with disabilities, but it has been long sought by the disability rights community. Inclusion of the initiative as an optional component of the health care reform law was considered a partial victory.[33] It had been hoped that all Medicaid recipients would be eligible for attendant care services but under the final rules, only those in need of institutional care or the equivalent would be eligible. [34]

This option has a slightly higher threshold for financial eligibility than regular provisions of Medicaid expansion (138 percent of federal poverty level). The floor for services under CFCO is 150 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). States that currently extend Medicaid nursing home eligibility to incomes greater than 150 percent of poverty may cover higher-income individuals with the CFCO, but only for incomes up to the level that would qualify for Medicaid institutional coverage – up to 300 percent of SSI ($2,022 per month in 2010).[35]

Because CFCO is provided through a state plan amendment rather than a waiver, benefits must be made available statewide and may not limited by enrollment caps or other restrictions. Many, if not most, of those who would be eligible for CFCO are already eligible, because of the focus on individuals needing institutional care.

Community First Choice Option: A Program Outline

CFCO is designed to give those with functional limitations a choice between care in an institution or in their own homes or community. [36] Services for each participant are based on an assessment-driven individual care plan. The program has required and optional services.

Required Services:

- Assistance with activities and instrumental activities of daily living and health-related tasks, including hands-on assistance and supervision;

- Acquisition, maintenance, and enhancement of skills to complete those tasks;

- Back-up systems, such as beepers, that will ensure continuity of care and support;

- Training on hiring and dismissing attendants, if desired by the individual.

Optional Services:

- Transition costs, such as first month’s rent; utility deposits; and kitchen supplies, bedding, and other necessities for moving from a nursing facility to the community;

- Coverage for other items noted in a care plan that increase independence or substitute for personal assistance.

Excluded:

- home modifications;

- room and board;

- medical supplies, and;

- assistive technology (except items that would meet the definition of back-up systems to ensure care continuity).

Providers:

-

States can select one or more models for the delivery of CFC. Ideally, states will provide consumers with a robust system in order to increase choice. Services must be provided under a person-centered plan. “Agency Provider Model” includes a range of approaches, with the individual having the ability to select, train,

and dismiss their direct attendant, including: [37]

- Traditional agency-managed services

- Agency-with-Choice model where the agency operates solely as a fiscal intermediary

- “Self-Directed Model with service budget” including:

- Vouchers;

- Direct Cash Payments (similar to a Cash & Counseling model);

- Fiscal Agent;

- Family members, as defined by the Department of Health and Human Services, can provide services.

Providers are to be selected and services controlled by the individual or individual’s representative to the maximum extent possible. States must ensure that regardless of care model, services are provided in accordance with the Fair Labor Standards Act.

Requirements for states:

- Service availability: States must make services available statewide, with no caps or targeting by age, severity of disability, or any other criteria. Services must be provided in the most integrated setting appropriate, given an individual’s needs.

- Maintenance of Effort: During the first year, a state must maintain or exceed its prior year Medicaid expenditure level for included services provided to elderly individuals and people with disabilities.

- Implementation Council: States must establish a Development and Implementation Council to collaborate on program design and implementation. The council must have majority membership of the elderly, people with disabilities, or their representatives.

- Quality Systems and Data: States must develop quality systems that incorporate consumer feedback and monitor health measures. The state must submit program reports to the Department of Health and Human Services.

High incentives, lingering concerns

The Community First Choice Option offers a significantly higher share of federal match for services, but only one state has applied and been approved for this opportunity. In a study published this past summer, the United States Government Accountability Office found uptake slow in part because final rules were published only in May, and in part because states were concerned by perceived risks of the new option, including the following: [38]

- Prohibition of caps on enrollment and utilization is seen as a financial exposure.

- Not all services offered under existing waiver programs would be covered.

- Administrative costs could outweigh enhanced federal match.

- Lack of staffing prevented consideration.

- Overall reform is being prepared before targeted programs are dealt with.

- Some states are in the middle of transition of long-term support and service for the targeted population to managed care.

- Some states have just implemented a “money-follows-the person” program and have existing transition programs in place and under implementation.

In a sense, concerns mirrored the larger concerns about the Affordable Care Act itself.

Ohio is not considering this option, according to Eric Poklar of the Office of Health Transformation.[39] He emphasized, in response to a query, that Ohio already offers personal care attendant services under the waiver programs and that it has other priorities – other initiatives – to make such care better.

However, personal attendant care offered under waivers lack the broad accessibility of a plan option, and they lack enhanced federal match.

Anna Rich of the National Senior Law Center suggested that Ohio would benefit from the extra money provided by the CFCO, that the timing would be good, that California had had an easy transition with much help from the national Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and that Ohio’s desire to boost waiver enrollment made it appealing for our state. Rich also pointed out that most of those who would take advantage of the CFCO are likely to already be on Medicaid, so the program wouldn’t bring in new costly participants.[40]

Ohio ranks low among the states in terms of meeting the needs of those with developmental disabilities, according to the 2012 study: “The Case for Inclusion.” Although Ohio’s overall ranking is 34th among the states overall, and improved by 14 places since 2007, we still rank 44th among the states in meeting needs, based on waiting lists.[41] According to data provided by the Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities, county waiting lists for services for this community topped 40,000 in February of 2012. Many of these individuals may not be eligible for Medicaid and/or are not in need of institutional care, but provision of adequate home and community-based care is a problem. In April of 2011, the Legal Rights Service (now known as the Disability Rights Service), an advocacy organization, wrote in a letter to the Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities:

LRS is gravely concerned about the current size and pace of waiting lists in counties across the state for home and community-based services waivers. According to the Department’s own estimate, even after the Nancy Martin settlement, there are approximately 27,000 people with developmental disabilities who are presently institutionalized or at risk of institutionalization and who are on waiting lists for Medicaid waivers. Moreover, a person’s placement on a waiting list for a Medicaid waiver almost always remains static (or even moves downward on the waiting list), and even those who have been waiting for a decade or more have no realistic opportunity of receiving these needed community services anytime soon. An article in the Columbus Dispatch on April 27, 2011 entitled ‘Some families wait years for Medicaid home-care waivers’ highlighted the frustration of individuals with developmental disabilities and their families. The system must fundamentally change to comply with federal law.[42]

Advocates have asked the state to embrace federal enhanced funding opportunities for home and community-based care. As Governor Kasich took office in 2011, he was greeted with a series of letters from public policy leaders and experts across the state of Ohio. From LEAP (Linking Employment, Abilities and Potential), Deborah Nebel and Melanie Hogan wrote to encourage a personal care attendant option under the state plan with enhanced federal matching funds. Among other arguments, Nebel and Hogan said the initiative would strengthen the Medicaid program. “For the first time, federal Medicaid dollars can be spent on non-medical personal assistance (activities of daily living, one month rent, utility deposit, household goods). People with disabilities of all ages need these services to live and work in the community and would sustain services provided under HOME Choice which ends in 2016,” the letter said.[43] This is precisely what the Community First Choice Option would do.

Summary and recommendations

Ohio can bring in more federal funding by taking advantage of the Community First Choice Option and the Balancing Incentives Payment Program. It will save money spent on long-term care by providing more care – at enhanced federal Medicaid match rates – in the home and community. By broadening availability of services – the personal attendant care service - it can create personal and health care jobs in the community.

It is the responsibility of the state to explore significant federal funds for important programs at budget time. Many of the directors’ letters on last fall’s budget requests to the governor last fall emphasized the importance of federal funding sources to the pending budget. The Community First Choice Option and the Balancing Incentives Payment Program are two excellent opportunities to bring in federal funds and better meet Ohio’s needs.

[1] H. Stephen Kaye, Mitchell P. LaPlante, and Charlene Harrington, “Do Noninstitutional Long-Term

Care Services Reduce Medicaid Spending?” Datawatch, January-February 2009 at http://bit.ly/Vevks4.

2 National Council on Aging, “BIPP annual FMAP increase estimates” at http://bit.ly/Wid2XX.

[3] Unified Long-Term Care System Advisory Group, “Nursing Facility Reimbursement Subcommittee Report to the Ohio General Assembly,” December 21, 2012, Accessed through Gongwer Ohio on Dec. 28, 2012 at http://1.usa.gov/W9u3EE.

[4] “California First State To Receive Approval for Services Under Community First Choice Option,”The Arc, Capital Insider, 9/4/2012 at http://bit.ly/112jSEZ.

[5] Center for Disability Rights New York State, “1915(k) Community First Choice Option in New York State” at http://www.ilny.org/downloads/legislative/CFC%20in%20NYS%20-%20Handout%20for%20NYAIL.pdf.

[6] Medicaid Task Force, Options for Cost Savings, Report to the Governor, May 4, 2011 at http://1.usa.gov/X5gMKN.

[7] Vernon K. Smith, Ph.D., Kathleen Gifford and Eileen Ellis (Health Management Associates) and Robin Rudowitz and Laura Snyder (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured - Kaiser Family Foundation), “Medicaid Today; Preparing for Tomorrow A Look at State Medicaid Program Spending, Enrollment and Policy Trends

Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2012 and 2013,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, October 2012 at http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/8380.pdf. The footnote to this paragraph in the report says that Maryland is looking at implementing the Community First Choice option in 2014.

[8] New York Times, Medicaid Navigator at http://nyti.ms/bv6Mnh.

[9] Id.

[10] This is not the enhanced rate; taken from Table 1 – Federal Medical Assistance Percentages and Enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentages, Effective October 1, 2012-September 30, 2013 (Fiscal Year 2013). Federal Register Volume 76, Number 230 (Wednesday, November 30, 2011), [Notices][Pages 74061-74063] From the Federal Register Online via the Government Printing Office at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-11-30/html/2011-30860.htm.

[11] House Health and Human Services Subcommittee Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, Office of Ohio Health Plans Executive Budget Recommendations SFY 2012-2013 John McCarthy, Medicaid Director April 4, 2011 at https://jfs.ohio.gov/oleg/McCarthySubcommitteeTestimony040411.pdf.

[12] Ohio Office of Health Transformation, “Rebalancing Medicaid Long Term Care” at http://1.usa.gov/X5h5VP.

[13] Kaiser Commission on Medicaid Facts, Medicaid and long term care services and supports, June 2012 at http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/2186-09.pdf.

[14] National Health Policy Forum, “National Spending for Long Term Services and Supports,” 2/23/2012 at http://www.nhpf.org/library/the-basics/Basics_LongTermServicesSupports_02-23-12.pdf.

[15] Ohio Office of Health Transformation website at http://1.usa.gov/UvzDjw.

[16] Ohio Office of Health Transformation, “Rebalancing Medicaid Long Term Care” at http://1.usa.gov/X5h5VP.

[17] Roland Hornbostel, “Unfinished Business: Rebalancing Ohio’s System of Long-Term Services and Supports for Elders and People with Physical Disabilities,” State Budgeting Matters, Center for Community Solutions at http://bit.ly/X2wkgM.

[18] National Health Policy Forum, “National Spending for Long Term Services and Supports,” 2/23/2012 at http://www.nhpf.org/library/the-basics/Basics_LongTermServicesSupports_02-23-12.pdf.

[19] Joint Legislative Committee for Unified Long-Term Services and Supports Testimony of John McCarthy, Medicaid Director Office of Ohio Health Plans, Ohio Department of Job and Family Services February 21, 2012 at http://www.healthtransformation.ohio.gov/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=-GYEkKv_qW0%3D&tabid=104.

[21] Joint Legislative Committee for Unified Long-Term Services and Supports Testimony of John McCarthy, Medicaid Director Office of Ohio Health Plans, Ohio Department of Job and Family Services May 3, 2012 at http://www.healthtransformation.ohio.gov/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=-x1ReskdhYc%3D&tabid=104.

[22] Gongwer-Ohio, CMS Approves Medicare-Medicaid Duals Project; Savings Expected To Total $243 Million

Volume #81, Report #240, Article #6--Wednesday, December 12, 2012.

[23] Joint Legislative Committee for Unified Long-Term Services and Supports Testimony of John McCarthy, Medicaid Director Office of Ohio Health Plans, Ohio Department of Job and Family Services May 3, 2012 at http://www.healthtransformation.ohio.gov/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=-x1ReskdhYc%3D&tabid=104.

[24] Balancing Incentives Payment Program at Medicaid.gov, http://bit.ly/KTjjSN.

[25] States that spend less than 25 percent on home and community based care are eligible for a 5 percent increase in FMAP for the services under BIPP; those with 25 to 50 percent, like Ohio, are eligible for a two percentage point boost. (see Medicaid.gov, “Balancing Incentives Payment Program” at http://bit.ly/KTjjSN.

[26] Director John Martin’s February 22, 2012 testimony stated: Thanks to your support in the budget, Ohio is on the path to meeting these benchmarks. HB 153 increased funding for all long-term services and supports by $166 million and rebalanced where the money is spent, increasing HCBS funding from 36 percent of Medicaid spending in SFY 2011 to 42 percent in SFY 2013 and decreasing the share spent on institutions from 64 percent to 58 percent over the same period. The operating protocols that BIPP requires are aligned with Ohio’s plans to integrate Medicaid and Medicare benefits for dual eligibles and create a single HCBS waiver. Ohio Medicaid is currently reviewing the BIPP requirements and considering whether to apply for the program.

[27] Text of House Bill 153 of the 129th General Assembly, Section 309.35.10. “Rebalancing Long-term care”

[28] Email from Eric Poklar of the Office of Health Transformation, November 21, 2012.

[29] “Affordable Care Act Supports States in Strengthening Community Living,” press release from United States Department of Health and Human Services, February 22, 2011 at http://1.usa.gov/gV0m4s.

[30] California receives first in nation approval for new community based care option for at-risk seniors and persons with disabilities, California Department of Social Services Press Release, August 31, 2012 at http://bit.ly/VhbKJV.

[31] New York Center for Disabilities at http://bit.ly/WieDgH.

[32] State of Alaska, Department of Health and Social Services, “Medicaid Task Force: Options for Cost Savings.” May 4, 2011 at http://dhss.alaska.gov/Commissioner/Documents/medicaidtaskforce/files/MTF_Final_Report_To_Gov.pdf

[33] Michelle Diamont, “Feds begin roll out of Community living program,” Disabilityscoop, September 5, 2012 at http://www.disabilityscoop.com/2012/09/05/feds-rollout-community-living/16385/

[34] There was much deliberation over eligibility for CFCO. The Federal Government’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) initially took a broader view, the view that only those above 150% of the federal poverty level (FPL) would have to qualify for an institutional level of care, i.e., “but for” HCBS, the individual would require the level of care in a hospital, nursing home, intermediate care facility for developmentally disabled, or institution for mental disease. After further consideration, including discussions with stakeholders, CMS reversed this position in the final rule so that now all individuals must meet the institutional level of care to qualify for CFC. There is, however, still some distinction that may exclude certain special categories of “higher” income beneficiaries with limited benefit packages.[34]

Federal Register/Vol. 77, No. 88/Monday, May 7, 2012/Rules and Regulations, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 42 CFR Part 441 [CMS–2337–F] RIN 0938–AQ35Medicaid Program; Community First Choice Option, AGENCY: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. ACTION: Final rule – pp26828 at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2012-05-07/pdf/2012-10294.pdf

[35] In Ohio, if individuals meet the institutional level of care they can be eligible for waiver services if they have income less than 300% of the SSI standard of need. For nursing home care, income can be higher as long as monthly income is less than the nursing home’s Medicaid reimbursement rate.

[36] “Long-Term Services Health Reform Provisions: Community First Choice Option. Families USA: The Voice for Health Care Consumers, at http://www.familiesusa.org/issues/long-term-services/health-reform/community-first-choice-option.html

[37] New York Center for Disability Rights at http://bit.ly/WieDgH.

[38] United States Government Accountability Office, “States’ Plans to Pursue New and Revised Options for Home- and Community-Based Services” June 2012 at http://www.gao.gov/assets/600/591560.pdf

[39] E-mail from Eric Poklar, Director of Government Affairs and Communications Governor's Office of Health Transformation dated December 14, 2012: “Ohio already covers the individuals and services that are provided through the Community First Choice Program through its 1915(c) waivers. Those waiver programs are mature programs with extensive case management. Ohio is always looking to improve the program and decided to start improvements through the ICDS initiative. One of the facets of the ICDS initiative is to break down the barriers between the 5 HCBS waivers to ensure a person simply gets the services he or she needs. The waiver should not dictate the services. What a person needs to keep them independent and in the community should dictate the services.”

[40] Anna Rich, e-mail of 12/13/2012: “I think that an additional important point to make on CFCO is that implementing it in combination with the duals demo is really perfect timing, because the state is (we hope) already thinking through issues like how plans will do assessments, care plans, etc—that thinking could be combined with implementation of CFCO requirements like the person-centered service plan, so as not to require extra work. Also, the experience in California was that CMS was definitely willing to work with the state to make the transition to CFCO from our current personal care services option as seamless as possible, keeping the administrative burden minimal and maximizing the benefit of the increased match. From the beneficiary perspective, the transition has been easy. I also don’t think Ohio should be scared by the fact that it is a statewide state plan benefit rather than a capped waiver benefit because your waivers are so underenrolled. Also, Medicaid expansion or so-called “woodwork effect” should not scare the state off because CFCO is for people who need an institutional level of care—they are likely already on Medicaid.”

[41] “The Case for Inclusion 2012,” United Cerebral Palsy at http://bit.ly/JqHW8G.

[42] Letter from the Ohio Legal Rights Organization to Gregory W. Swart, Senior General Counsel Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities, April 28 2011 at http://bit.ly/14lGtvW.

[43] Journal of the Center for Community Solutions, “Dear Governor”, Center for Community Solutions, 2010 at http://www.communitysolutions.com/associations/13078/files/PA%20deargov%202010.pdf.

Tags

2013Affordable Care ActBudget PolicyRevenue & BudgetWendy PattonPhoto Gallery

1 of 22