Cuts to women's health care could cost more young lives

May 07, 2015

Cuts to women's health care could cost more young lives

May 07, 2015

Ohio's infant death rate declared a crisis, yet proposals to limit women's health care can only make it worse.

Contact: Wendy Patton, 614.221.4505

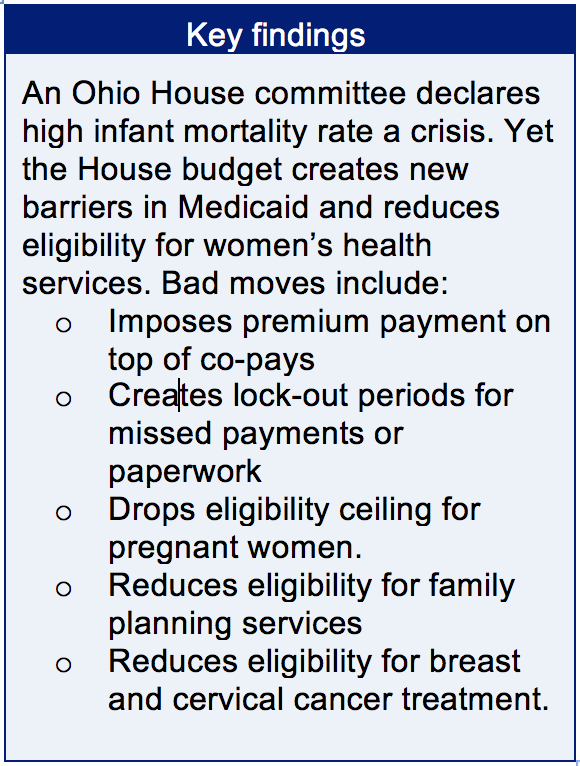

With Ohio ranking near the bottom of the 50 states in infant mortality, lawmakers should prioritize action and investment that will lead to improvements. Accepting federal money to allow more families to get Medicaid in 2014 was an excellent initial move. Yet, the new Kasich budget proposes cuts to health care for low-income women. The House would make it harder for low-income women to access and maintain health care through Medicaid.

With Ohio ranking near the bottom of the 50 states in infant mortality, lawmakers should prioritize action and investment that will lead to improvements. Accepting federal money to allow more families to get Medicaid in 2014 was an excellent initial move. Yet, the new Kasich budget proposes cuts to health care for low-income women. The House would make it harder for low-income women to access and maintain health care through Medicaid.The Senate should reverse budget cuts in women’s health care and eliminate changes in Medicaid that would act as barriers to care. It should retain Medicaid reforms that allow more women to see a doctor and invest in initiatives to reduce infant mortality.

Infant mortality

Babies that die before their first birthday are included in the count of infant mortality. The infant mortality rate is an estimate of the number of infant deaths for every 1,000 live births. This rate is commonly used to measure the health and well-being of a nation, because factors affecting the health of entire populations can also affect the mortality rate of infants.[1]

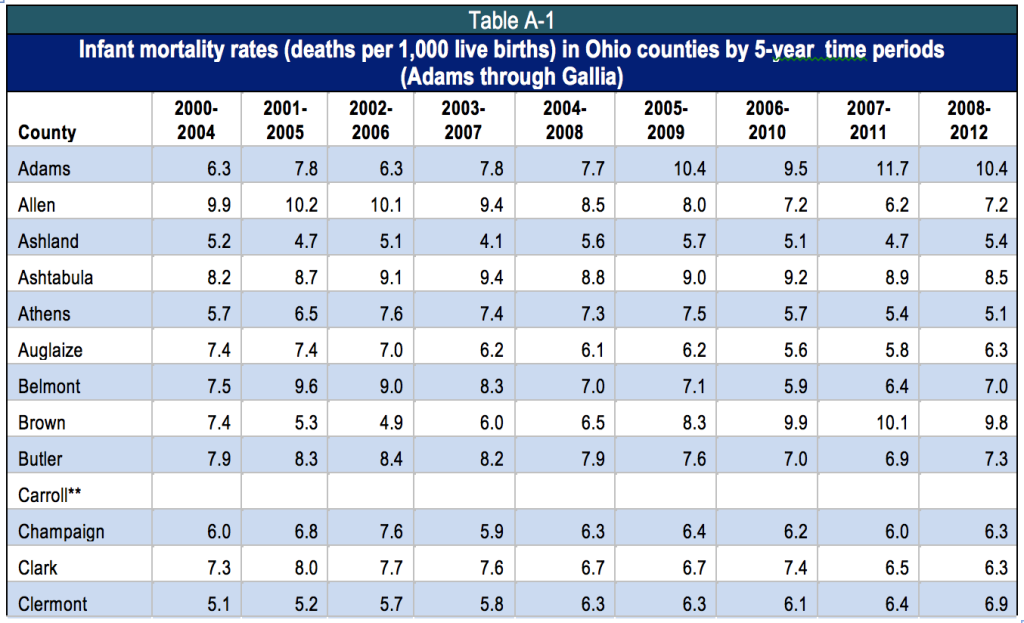

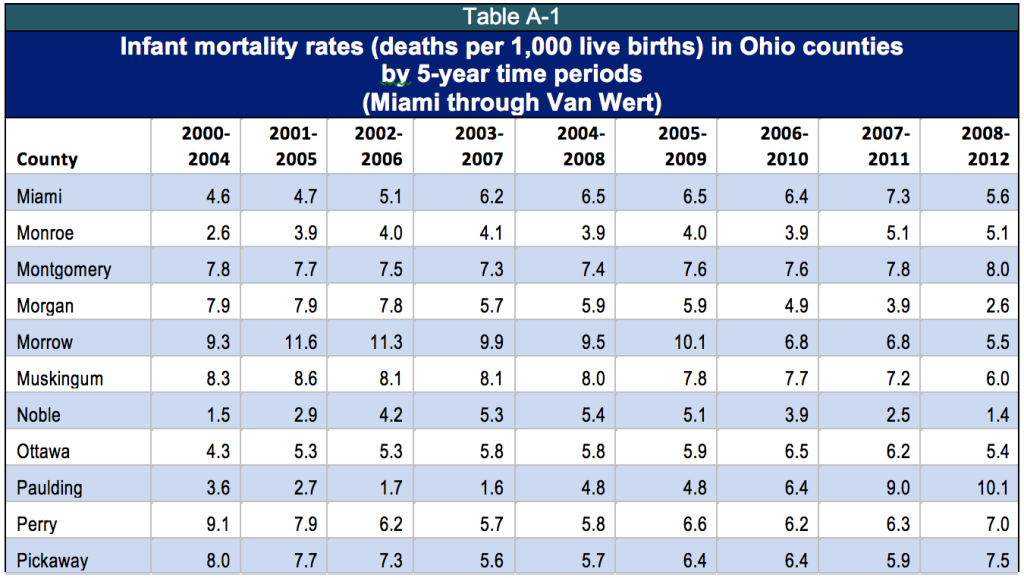

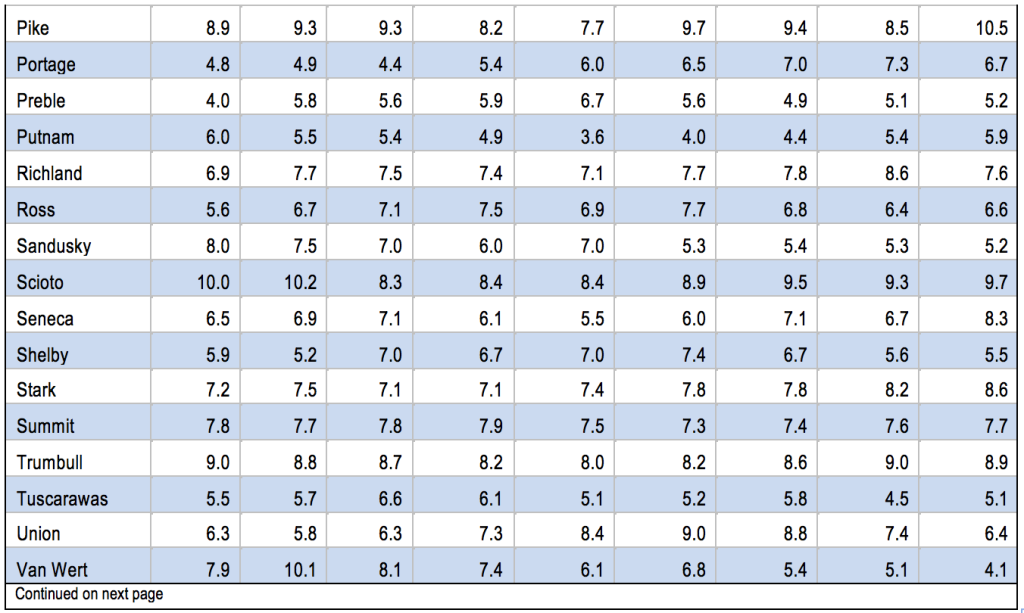

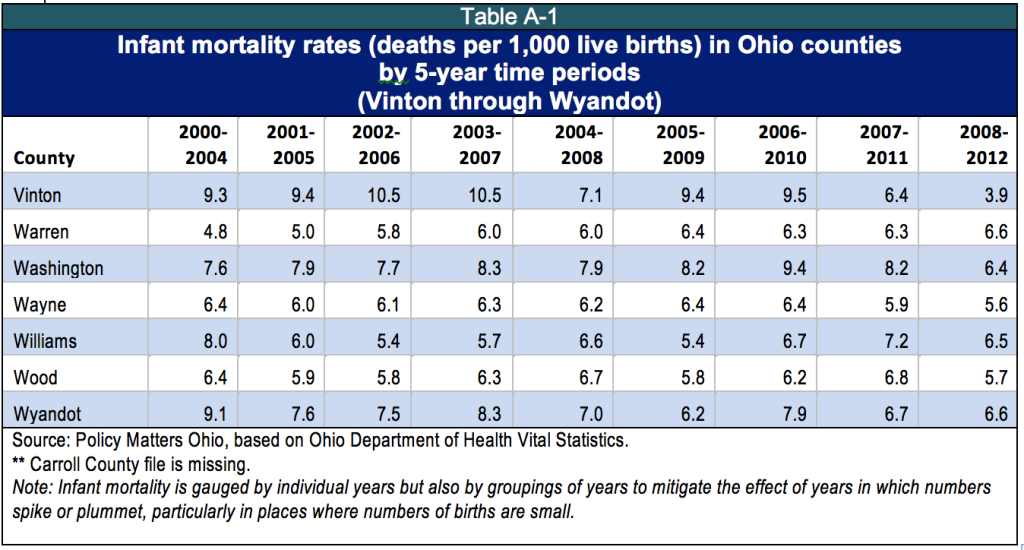

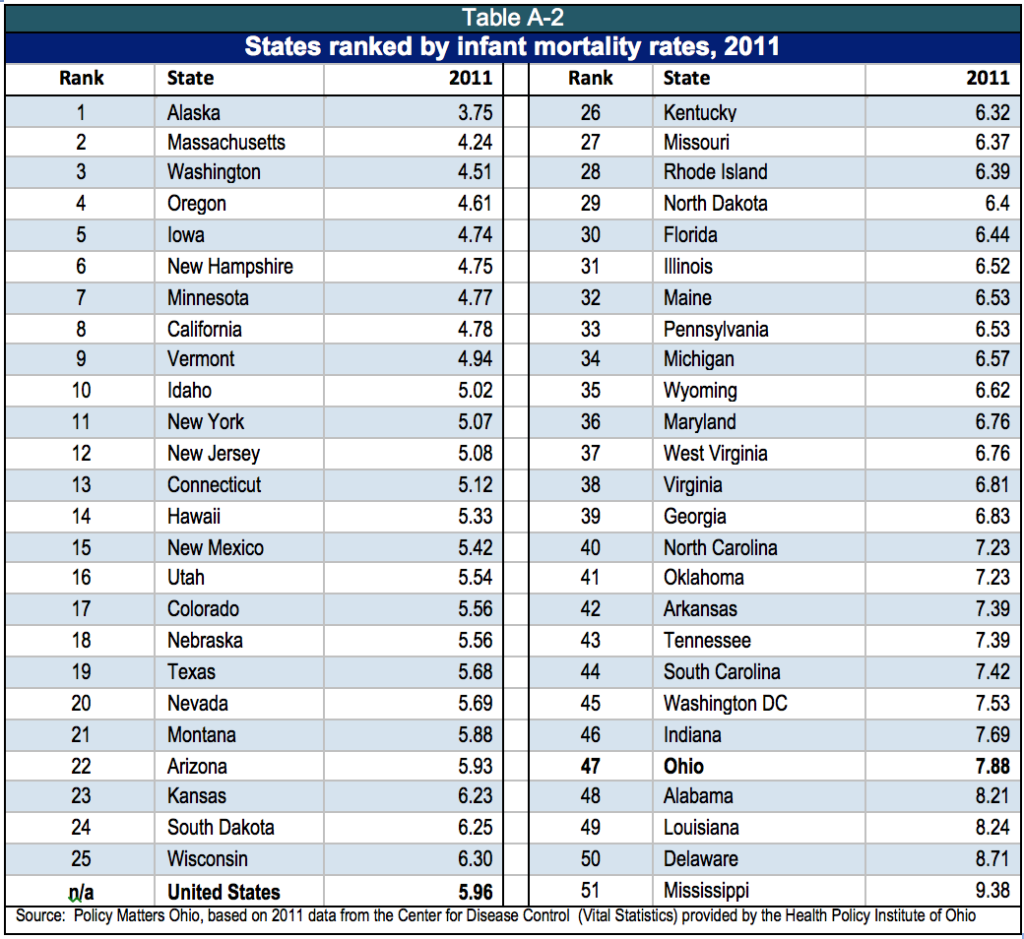

In 2011 Ohio’s infant mortality rate was 7.9 per 1,000, the fifth highest among the 50 states and the District of Columbia.[2] Cleveland was dubbed the ‘infant mortality capital’ of the United States in the award-winning 2014 television series “Fault Lines.”[3] A number of Cleveland neighborhoods had infant mortality rates above 27 deaths per 1,000 births: Hough, Mount Pleasant, Kinsman and South Collinwood - worse than in North Korea, Uzbekistan and Vietnam.[4] Rural Ohio has pockets of abysmal infant mortality as well. Adams, Highland, Madison, Paulding and Pike Counties had infant mortality rates of over 10 per 1,000 in the 2008-2012 period, worse than Mississippi - or Serbia.[5]

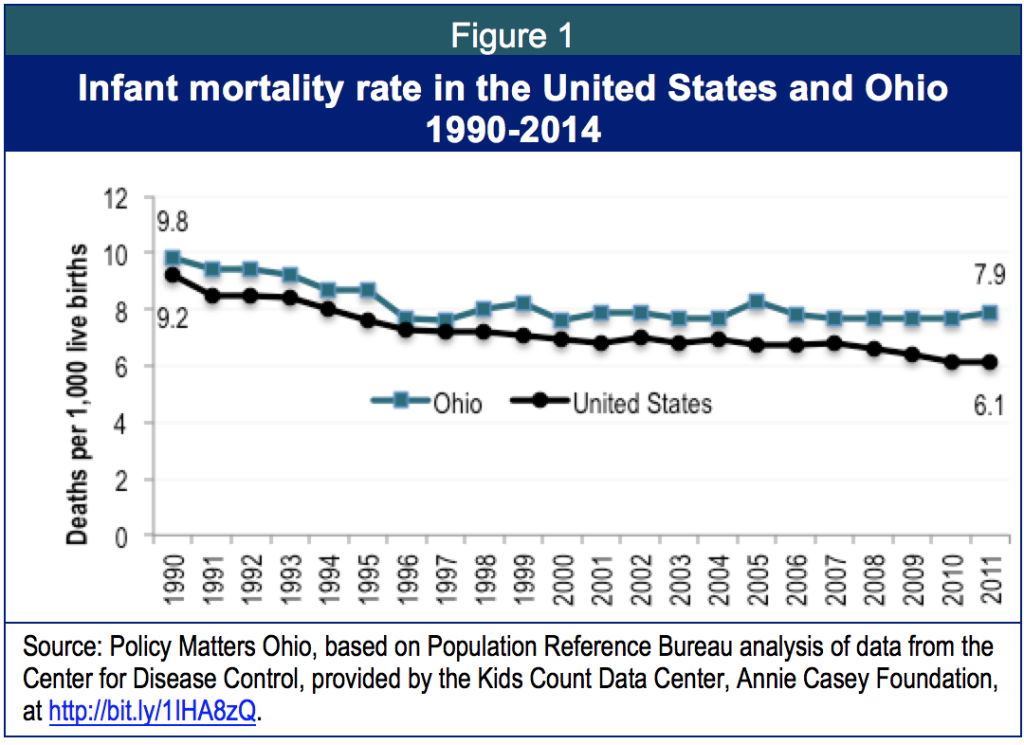

Infant mortality in Ohio and the nation

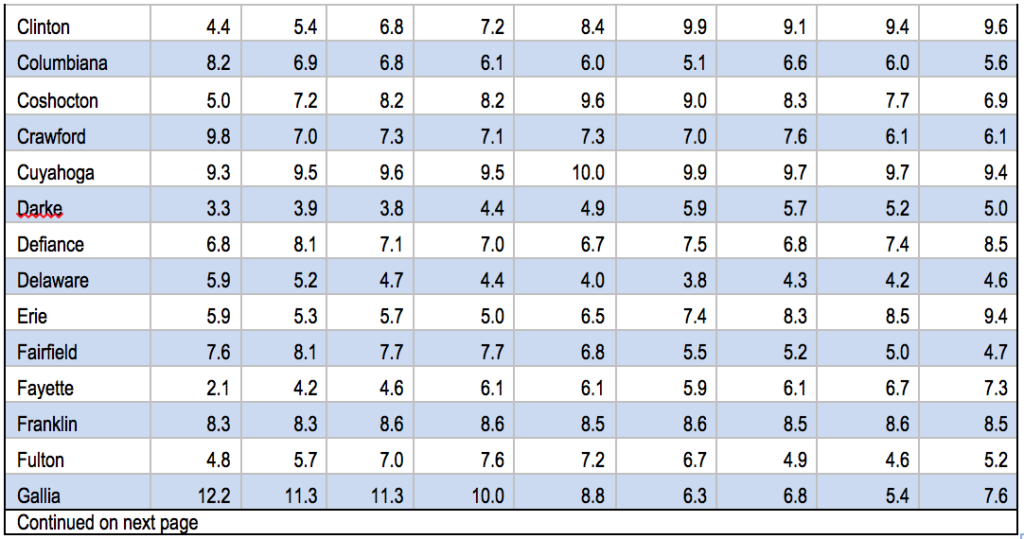

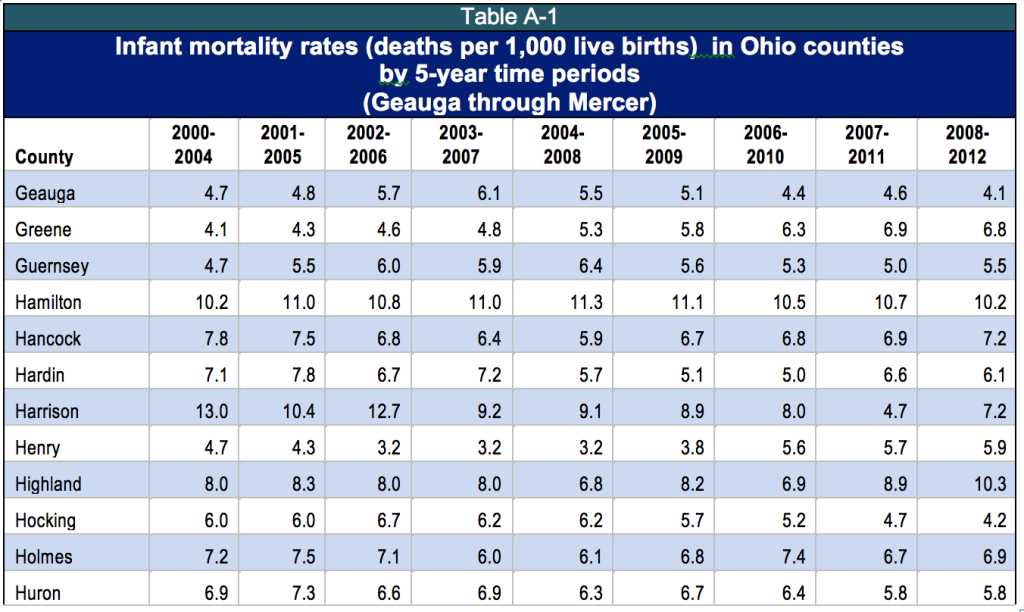

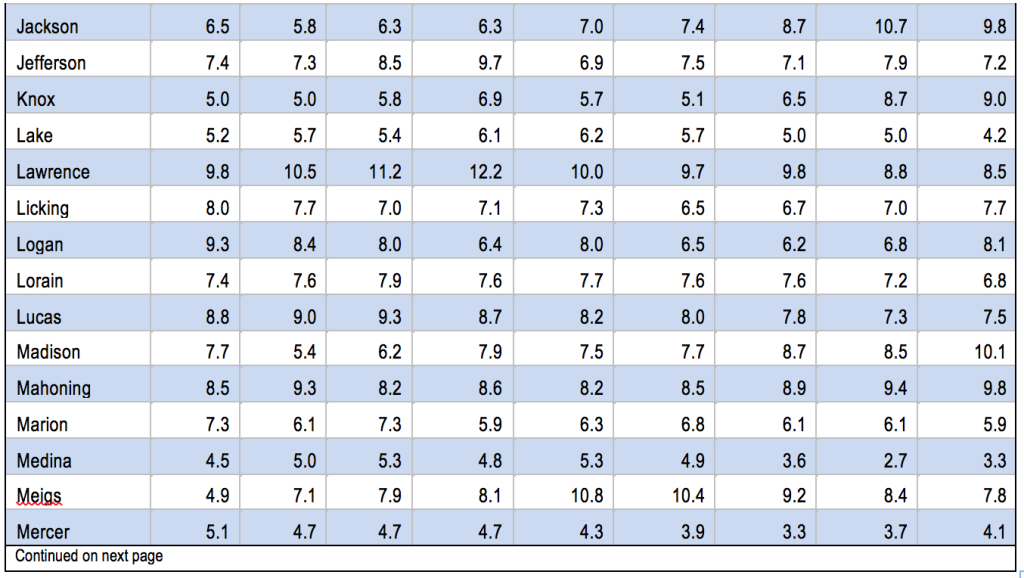

Figure 1 shows that Ohio’s infant mortality rate has been higher than that of the nation for years. In 2011, infant mortality was 6.1 per 1,000 births for the United States and 7.9 for Ohio.[6] There is also dramatic variation among counties (See Appendix, Table A-1).

In 2006, Ohio’s infant mortality rate ranked 38th among the states and the District of Columbia.[7] In 2011, it was 47th (See Appendix, Table A-2). The infant mortality rates of other states dropped while Ohio’s remained at about the same level.

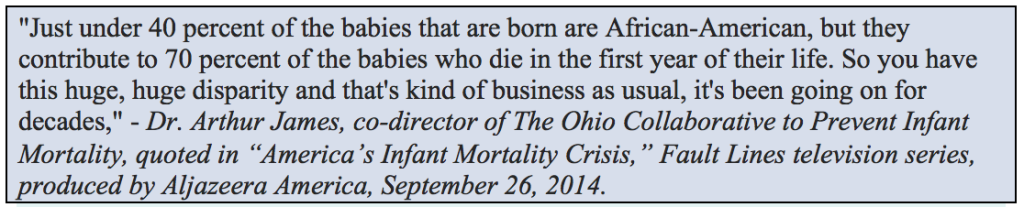

The infant mortality rate in 2011 for the state of Ohio was 7.9 per 1,000, but among black Ohioans, it was 16 per 1,000.[8] As an indicator for the well-being of a people or a state, this tells the story of disparity in America and in Ohio.

Mother’s health matters

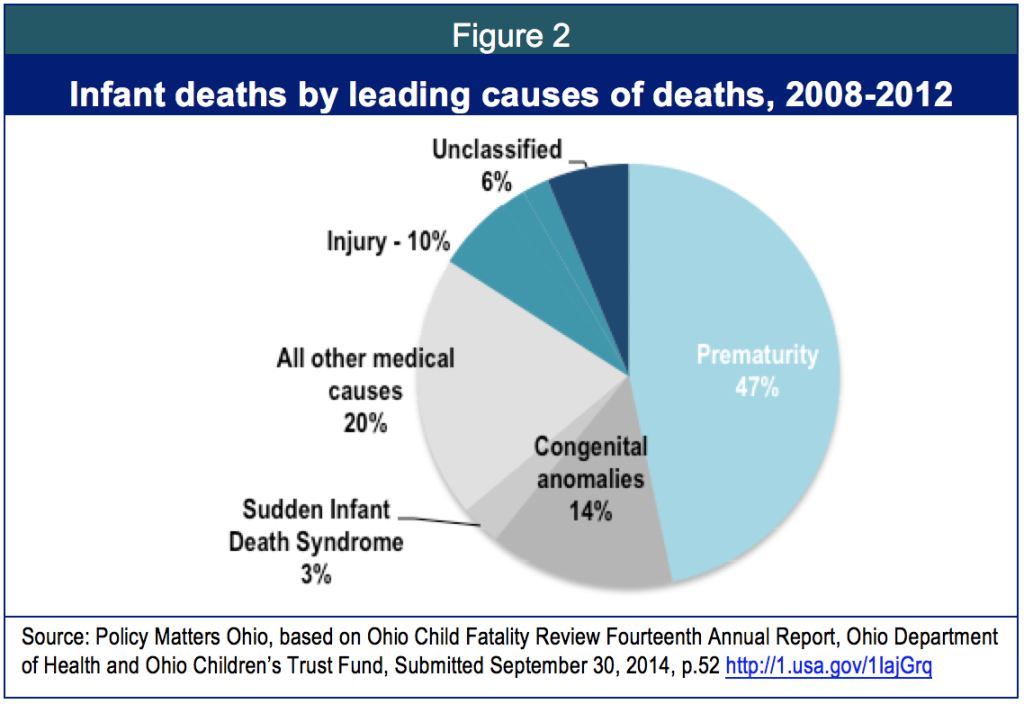

Many things contribute to infant mortality. When multiple causes related to prematurity are grouped, premature birth is the leading cause of infant mortality in the United States, accounting for over a third of all infant deaths.[9] Recent research has found infant death after the initial birth period among “less advantaged” Americans is more significant than previously thought.[10] However, the problem of premature birth in the United States is well known, and has drawn international attention. The watchdog group “Save the Children” reduced the ranking of the United States on its international Mother’s Index to among the lowest of developed nations because of high infant mortality. They found too many women in the United States – especially poor mothers – lacked sufficient access to medical care, leading to premature births.[11]

In Ohio, too, premature delivery is the leading cause of infant mortality. Congenital anomalies – like heart defects – are another leading factor. Injury and sudden infant death account for smaller categories. (Figure 2).

Mother’s health matters not just during pregnancy, but also before and after. The Centers for Disease Control identified key factors associated with pre-term birth,[12] including:

- Low or high maternal age

- Racial/ethnic heritage

- Low income or socioeconomic status

- Infection

- Prior pre-term birth

- Carrying more than one baby (twins or more)

- High blood pressure during pregnancy

- Smoking

- Alcohol use

- Late prenatal care

- Maternal stress

Medicaid and preventing infant mortality

In 2013, the Kasich administration broadened Medicaid eligibility to include low-income working adults earning up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (about $22,000 for a mother and child). This provides access to care for diseases that can cause infant mortality, an important step toward lowering infant mortality. The current Medicaid system goes further for critical components of care, covering pregnancy, family planning services and treatment for breast and cervical cancer for women earning up to 200 percent of poverty (about $32,000 for a mother with one child).

Medicaid is crucial to maternal and child health care in the United States, supporting over 40 percent of births.[13] Research shows Medicaid can reduce infant mortality for women who face high risk. Young pregnant women enrolled in Medicaid, for example, have been found to have reduced infant mortality, because prenatal care started earlier.[14] Family planning services reduce infant mortality by helping women plan for pregnancy and space births properly. Treatment for breast and cervical cancer improves maternal health by addressing the two most common forms of cancer in women. These three measures, taken together, are considered important health interventions for developing nations.[15] In a state with third-world levels of infant mortality in some neighborhoods or among some populations, employing strategies used in developing nations makes sense.

Medicaid coverage changes in the budget bill

The proposed budget for the next two years reshapes Medicaid services for many enrollees, including women of childbearing age. Changes include new premium payments for patients and penalties – a 12-month suspension of care if payments or paperwork are late. These changes will make it more difficult for women to access health care consistently.

The proposed budget for the next two years reshapes Medicaid services for many enrollees, including women of childbearing age. Changes include new premium payments for patients and penalties – a 12-month suspension of care if payments or paperwork are late. These changes will make it more difficult for women to access health care consistently.

The budget also narrows Medicaid eligibility for pregnancy, family planning, breast cancer treatment and cervical cancer treatment, reducing eligibility from 200 percent of poverty to 138 percent. Women can seek subsidized coverage in the commercial market under the Affordable Care Act during the annual “open enrollment” period, but there are cracks through which they can fall. A low-income working woman can be stranded without coverage during a pregnancy, increasing her risk of losing the baby.

- Waiting for open enrollment: Unlike marriage or the birth of a child, pregnancy does not qualify for a special enrollment period in the subsidized federal exchange like Ohio’s. An uninsured woman who becomes pregnant outside of an open enrollment period will not be able to enroll in marketplace coverage until the next open enrollment period comes around – and, it only comes around once a year. Many low-income pregnant women who didn’t sign up for coverage in the health care marketplace will have few options for prenatal care if Medicaid eligibility is cut back.

- The “Family Glitch:” Eligibility for a federal health care subsidy is determined in part by access to “affordable” coverage. The definition of “affordable” does not consider the cost of a family If the cost for an individual plan is less than 9.56 percent of household income, it is deemed affordable, even if what the worker needs is a family plan. Thus, the whole family can be locked out of access to tax credits and cost reductions because the formula considers the family able to buy individual coverage that won’t help them.

- Low-to-middle income women may not be able to afford coverage, even in the marketplace. For example, a pregnant woman earning about $32,000 for a family of three pays about 4 percent of her household income for coverage in the marketplace, even with the federal subsidy. Depending on household and work-related expenses (including school loans), the 4 percent may be unaffordable. While prenatal care should be included at no cost as a preventive service, deductibles and other cost sharing would apply to labor and delivery.

- Working mothers in the low-wage labor market have fluctuation in pay that may lead to inconsistency in care: In the low-wage labor market, temporary jobs start and stop, hours rise and fall with seasonal demand and plants, offices and stores open and close. A pregnant mother on Medicaid may land a temporary job that pays enough to raise her above the eligibility ceiling for Medicaid. That’s a good thing, but getting commercial coverage in the federal exchange may take a month and a half, depending on the timing of her application. That is too long to wait for health care during a pregnancy. If her temporary job ends, she can access Medicaid, but if something else comes along, she faces another gap in care.

- If low-income pregnant women remain uninsured, they may not get the prenatal care needed to have a safe, full-term delivery and healthy child: Research has shown that prenatal care reduces low-weight and premature births. Moreover, it saves money. The cost of hospitalizing a premature baby in a neonatal intensive care unit is around $5,000 per day; 100 days can cost upwards of a half million dollars. The health system bears the unreimbursed cost of the uninsured. The mother and baby bear the long-term effect of the medical crisis.

- Poverty compromises access to comprehensive care in the critical first year of life. A baby born to a mother covered by Medicaid is automatically eligible for Medicaid coverage for one year, regardless of changes in circumstances that may affect the baby’s eligibility. Cutting Medicaid for pregnant women will no longer automatically protect coverage for babies born to women in this income range during that first defining year in which babies make it to childhood or – in the case of too many Ohio children – don’t.

In recent years, Ohio shaped Medicaid to give low-income working women access to health care, particularly care that helps with pregnancy, family planning and common cancers. These improvements in health care for mothers are an excellent foundation for a long-term strategy to reduce infant mortality. Lawmakers need to retain the current Medicaid program structure, particularly in the areas of women’s health services.

The Ohio Senate has the opportunity to eliminate the proposal of the House budget for premiums, penalties and other changes that would act as barriers to care for too many. They can reject the executive budget proposal to reduce Medicaid eligibility for pregnancy, family planning services and treatment of breast and cervical cancer. They have the chance to address the state’s infant mortality crisis by protecting maternal health care.

Appendix: Table A-1: 2011 Infant Mortality Rates by County, 2000-2012

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Infant Mortality at http://1.usa.gov/1j1QbMj

[2] Population Reference Bureau, analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Multiple Causes of Death Public Use Files for 2006-2011From Kids Count data center, Annie Casey Foundation, at http://bit.ly/1IHA8zQ.

[3] Fault Lines: America’s Infant Mortality Crisis, Aljazeera America, September 26, 2014 at http://alj.am/1Iai0hq

[4] Tom Feran, “Expert says infant mortality rate near University Circle exceeds that of some Third World countries, The Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 12, 2013 at http://bit.ly/1ESYxRt.

[5] Ohio data from Ohio Department of Health (see Appendix); international data from the World Health Organization.

[6] Population Reference Bureau, Op.Cit.

[7] Population Reference Bureau, Op.Cit.

[8] Ohio Department of Health, Infant Mortality Data, Office of Vital Statistics at http://1.usa.gov/1EUNozr

[9] Mathews TJ, MacDorman, MF. Infant Mortality Statistics from the 2009 Period Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 61 no 8. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2013, cited in U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Child Health USA 2013. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013. At http://1.usa.gov/1KdqJOR. See also, Child Health USA 2014: Health Status and behaviors; same source; accessed at http://1.usa.gov/1GMDwER

[10] Alice Chen, Emily Oster and Heidi Williams, “Why is infant mortality higher in the US than in Europe? “National Bureau of Economic research and the University of Chicago, September 2014 at http://economics.mit.edu/files/9922.

[11] Save the Children’s “Mother’s Index” ranks 168 nations according to where the best places to be a mother would be. The U.S. dropped five spots for 2012, and declined further in the 2014 report. See Michelle Castillo, CBS News, May 7, 2013 at http://cbsn.ws/LYLzJland State of the World’s Mothers, 2014 at http://bit.ly/1ci6ULN

[12] Center for Disease Control, Factors Associated with Pre-term Birth, http://1.usa.gov/1E578wz

[13] Anne Rossier Markus, Ellie Andres, Kristina D. West, Nicole Garro, Cynthia Pellegrini, Medicaid Covered Births, 2008 through 2010, in the Context of the Implementation of Health Reform, Sept-Oct 2013 at http://www.whijournal.com/article/S1049-3867(13)00055-8/fulltext.

[14] Dawn Brintnell, Melanie Peterson-Hickey, David Stroud, Susan Castellano, Cheryl Fogarty, The Birth Certificate and Medicaid Data Match Project: Initial Findings in Infant Mortality, MN Department of Health and MN Department of Human Services, 2005 at http://bit.ly/1F46GEH;. See also Nancy Moss and Karen Carver, The effect of WIC and Medicaid on infant mortality in the United States, American Journal of Public Health, Vol 8, #9, September 1998;; Carol J. Rowland Hogue and Cynthia Vasquez,, Toward a Strategic Approach for Reducing Disparities in Infant Mortality, American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 92,#4, April 2002; U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Poverty in America: Economic Research Shows Adverse Impacts on Health Status and Other Social Conditions as well as the Economic Growth Rate,” 07-344, January 24, 2007 athttp://1.usa.gov/1IK4Qby

[15] Dara Lee Luca , Alyssa Shiraishi Lubet , Kristine Husøy Onarheim, David E. Bloom, Johanne Helene Iversen, Elizabeth Mitgang, Klaus Prettner, Benefits and Costs of the Women’s Health Targets for the Post-2015 Development Agenda, Copenhagen Consensus Center, November 2014 at http://bit.ly/1IdOcC4

Tags

2015MedicaidWendy PattonPhoto Gallery

1 of 22