Ohio’s childcare cliffs, canyons and cracks

May 08, 2014

Ohio’s childcare cliffs, canyons and cracks

May 08, 2014

Download summary (2pp)Download report (14pp)Press releaseOhio could improve the lives of many working moms this year by making public childcare work better for families and children. This study examines how a small increase in earnings causes families to lose childcare subsidies and see reductions to their family budgets.

Executive Summary

Access to quality childcare helps build pathways out of poverty for low-income families. In the short run, childcare serves as a critical work support that allows parents to work knowing their children are in good hands. In the long run, quality childcare gives low-income children the attention, care, stimulation and education they need for brain development and prepares them to do well in school.

Access to quality childcare helps build pathways out of poverty for low-income families. In the short run, childcare serves as a critical work support that allows parents to work knowing their children are in good hands. In the long run, quality childcare gives low-income children the attention, care, stimulation and education they need for brain development and prepares them to do well in school.

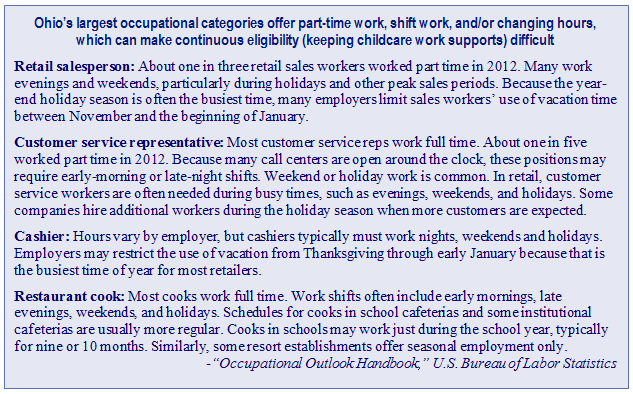

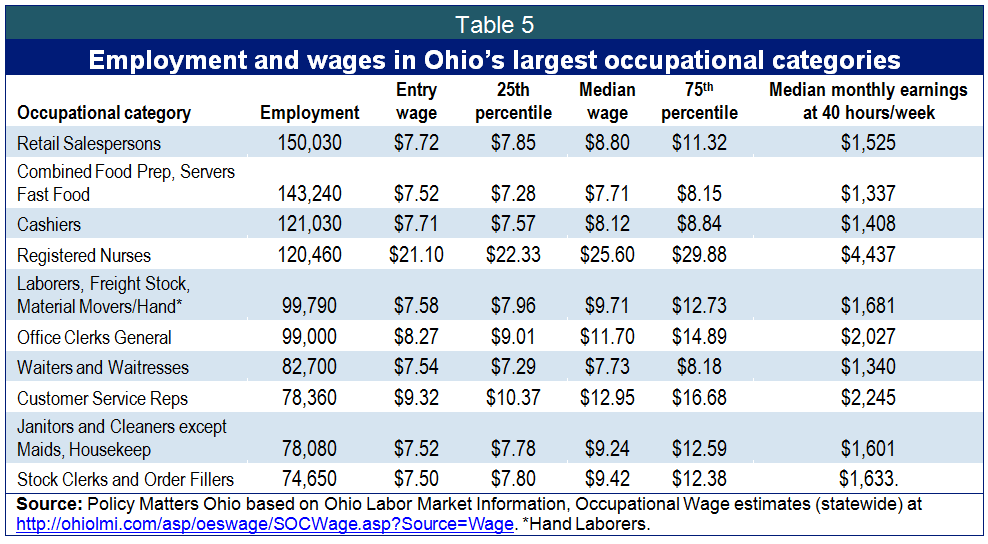

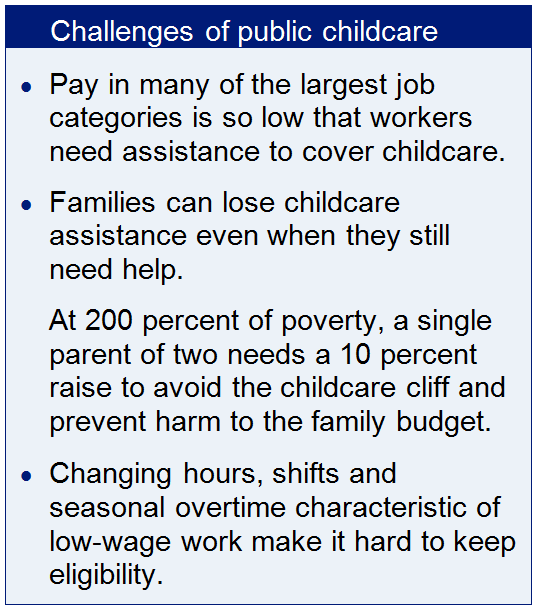

Childcare aid is often called a “work support.” Work supports are public benefits that allow families to survive in an economy with jobs that don’t pay enough. The largest occupational categories in Ohio pay far less than a family needs for self-sufficiency.

Work supports like childcare assistance are supposed to help families move from poverty to self-sufficiency. But for too many, the transition isn’t smooth: it is rough terrain, with cracks, cliffs and canyons.

The public childcare assistance program administered by the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services is the largest of several childcare programs the state sponsors; two-thirds of the funding is federal. In Ohio, the threshold of initial eligibility for public childcare assistance is 125 percent of the federal poverty level. While families can only enter the program at or below that level, they continue to receive childcare aid if they are in the system without interruption up to 200 percent of poverty, the ceiling for ongoing eligibility. Today Ohio ranks among the lowest of states in initial eligibility levels for this public childcare assistance. Once you are in, it is too easy to fall out.

The earnings cliff

The most commonly recognized place that people lose eligibility is at the income ceiling for the program. For families that enter the public childcare system at or under 125 percent of the federal poverty level, and have stayed in the system without interruption, earnings can increase up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level without loss of the work support. Family co-pays increase, but the share of income needed for childcare remains below 9 percent. Above 200 percent of the poverty level, the support ends and the family falls off the cliff. A parent of one in the Cleveland area would need a raise of about 10 percent ($1.68 per hour) to keep from suffering a net income loss.

Falling through the cracks

Many who leave childcare assistance do not do so because their income rises, but because something in their employment situation changes. The largest occupational categories in Ohio are low-wage jobs, and they are characterized by part time, seasonal, or shift work, all of which can bounce a family in and out of eligibility. Changes that impact eligibility must be reported within a specified window, along with employer letters, pay stubs, and class schedules. If there is an interruption in participation (a pink slip; illness; winter break), families can lose eligibility. They can re-enter only at the threshold of eligibility, at the bottom of the income ladder.

Caught in the canyon

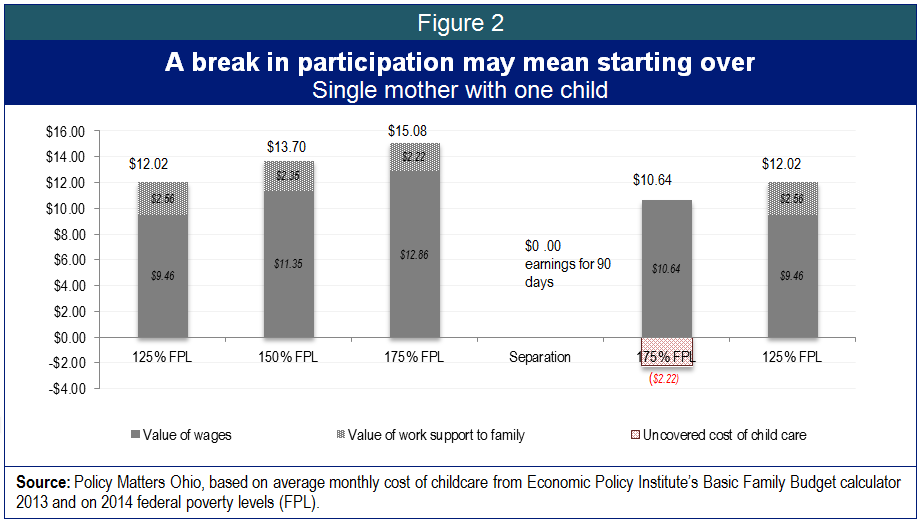

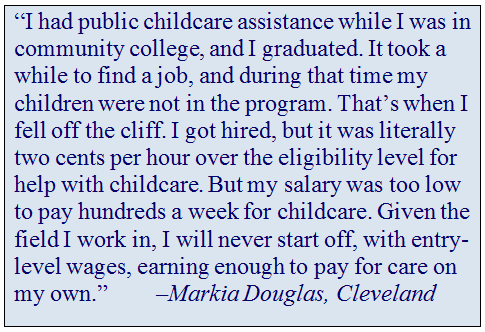

A parent who loses a job tries to re-enter the labor market where she left off; say, at $12.86 per hour, but she finds it is not worth hiring on at that level. She’ll bring home a lot less because she is above the level of initial eligibility (125 percent of poverty) so she can’t get her childcare assistance back. She does better starting again $9.46 per hour and getting back into the childcare assistance program. The problem is, she can’t advance in career or earnings by moving backwards.

Ohio’s economy doesn’t work well for low-earning families with young children. Nor does it work well for kids. A 2000 National Academies of Science report, Neurons to Neighborhoods, showed that brain development is most rapid during the first five years of life. Other studies have demonstrated that the benefits of childcare last well into adolescence. Interruptions in care reduce benefits for individual children, with a long-term societal impact.

The rough terrain of childcare doesn’t work very well for employers, either. Employers in low-wage sectors can have significant numbers of workers with childcare assistance. Around the level of the cliff, some find it hard to move experienced workers into higher positions. Some are finding what they thought was a skills gap is actually a problem in getting and keeping adequate childcare.

Access to consistent, quality childcare is essential to children, families, communities, and our economy. Yet today’s economy has far too many low-wage jobs that leave families unable to access high-quality childcare. With these low wages, everyone has to work, including both parents and other family members who might once have assisted with childcare. Public policy needs to support low-wage working families in a way that contributes to stability and supports early learning. Key steps the legislature could take include:

- Increase the income ceiling. To reduce the earnings cliff, the income ceiling should be extended to the self-sufficiency level by family size and county of residence.

- Accept children for 12 months at a time regardless of changes in family income or employment. This allows children to stay in one center, to build a platform of trust, and to start learning. It helps pressed caseworkers, eases financial and other stress of parents and helps teachers stabilize a classroom for sustained learning.

- Allow childcare providers to presume eligibility for public childcare assistance. Under Ohio law, approval for childcare assistance may take 30 days, but the parent needs the care, and the center needs the customer.

- Increase the income level for initial eligibility. Let families qualify for assistance until they earn enough to be self-sufficient. That way if a parent changes jobs, shifts, or gets sick, she can hire back in at the level where she left off.

Introduction

Access to quality childcare helps build pathways out of poverty for low-income families. In the short run, childcare serves as a critical work support that allows parents to work knowing their children are in good hands. In the long run, quality childcare gives low-income children the attention, care, stimulation and education they need for brain development and to do well in school.

Childcare aid is often called a “work support.” Work supports are public benefits that allow families to survive in an economy with jobs that don’t pay enough to raise a family. Most of the largest occupational categories pay far less than a family needs for self-sufficiency. Even two parents working full time may not be able to afford adequate childcare. Work supports help families bridge that gap.

Work supports like childcare assistance are supposed to help families move from poverty to self-sufficiency. But the transition can be difficult. Eligibility for help ends before a family reaches self-sufficiency. Changes in hours and shifts make it hard to stay in the system. Further, childcare is so expensive that parents may be reluctant to accept more hours, a raise or a better-paid job if it threatens eligibility.

A small increase in earnings can cause a family to lose a bigger childcare subsidy, resulting in a net loss. This is known as the childcare cliff. It happens in Ohio when incomes rise above 200 percent of poverty. There are also what we call cracks and canyons in childcare assistance. Changes in shifts, hours, class schedules or jobs, or problems with paperwork or notification, are the ‘cracks’ through which families can fall out of the system. Once out of the system they are in a canyon: they can’t regain the childcare work support unless they start over at the level of initial eligibility.

When families don’t get assistance, care can suffer. Some families find an informal arrangement for childcare that may or may not be adequate. Some may not be able to stay at work. Some families may break apart; some fall into poverty. As a result, children can struggle with learning, trust and behavior. Preventing such harm can have lifelong benefits.

Public childcare assistance

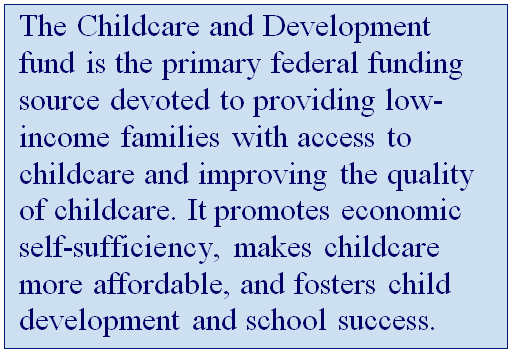

There are several childcare and early learning programs in Ohio, but the largest by far is the public childcare assistance program administered by the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services.[1] Federal dollars from the Childcare and Development Fund and from Temporary Aid for Needy Families (TANF) make up about two thirds of the funding. The remainder comes from state General Revenue Funds to match federal dollars.[2] In Ohio and across the nation, childcare assistance reaches about 17 percent of children living in or close to poverty.[3]

There are several childcare and early learning programs in Ohio, but the largest by far is the public childcare assistance program administered by the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services.[1] Federal dollars from the Childcare and Development Fund and from Temporary Aid for Needy Families (TANF) make up about two thirds of the funding. The remainder comes from state General Revenue Funds to match federal dollars.[2] In Ohio and across the nation, childcare assistance reaches about 17 percent of children living in or close to poverty.[3]

In fiscal year 2014 there will be 105,766 Ohio children in public childcare assistance at a projected cost of $589 million or $5,569 per child. The 2015 projection is 106,114 children at a cost of $592 million or $5,580 per child.[4]

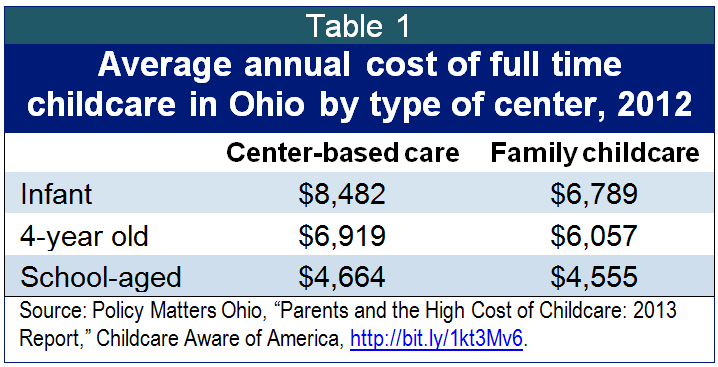

The state’s per-child cost of care is lower than the market price (Table 1). Parents share in the cost, and reimbursement of providers is set at the low end of the market.[5] In 2014 it is set at 16 percent of the 2012 market survey the state conducts on the childcare industry.[6]

The state’s per-child cost of care is lower than the market price (Table 1). Parents share in the cost, and reimbursement of providers is set at the low end of the market.[5] In 2014 it is set at 16 percent of the 2012 market survey the state conducts on the childcare industry.[6]

Childcare is a big-ticket item in the family budget. The U.S. Census found that as a national average, families with a working mother paid $7,436 for childcare in 2011. The cost of childcare rises quickly, outpacing inflation by 70 percent between 1985 and 2011.[7]

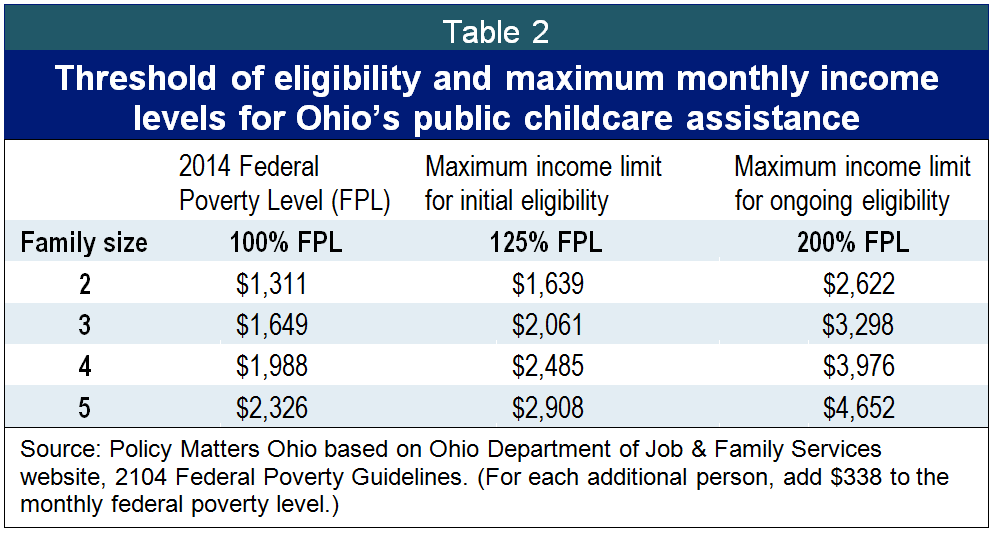

In Ohio, the threshold of initial eligibility for public childcare assistance is 125 percent of the federal poverty level.[8] While families can only enter the program at or below that level, they continue to receive childcare aid if they are in the system – without interruption – up to 200 percent of poverty, the ceiling for ongoing eligibility (Table 2). Eligibility levels have changed several times over the past decade in Ohio, dropping from 185 percent of federal poverty level to 150 percent, then back up and down, before being reduced to 125 percent of the federal poverty level in 2012.[9] The savings anticipated by the administration as a result of this final cut were $12 million annually – an extremely tiny share of Ohio’s budget, but a huge blow to poor working families earning around $25,000 per year and unable to afford childcare on their own.[10] Today Ohio ranks among the lowest of states in initial eligibility levels for public childcare assistance.[11]

The childcare cliff

The thresholds for eligibility in the public childcare assistance program, and the earning ceiling, are presented in Table 2. The most commonly recognized place that people lose eligibility for the childcare work support is at the income ceiling for ongoing eligibility, at 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

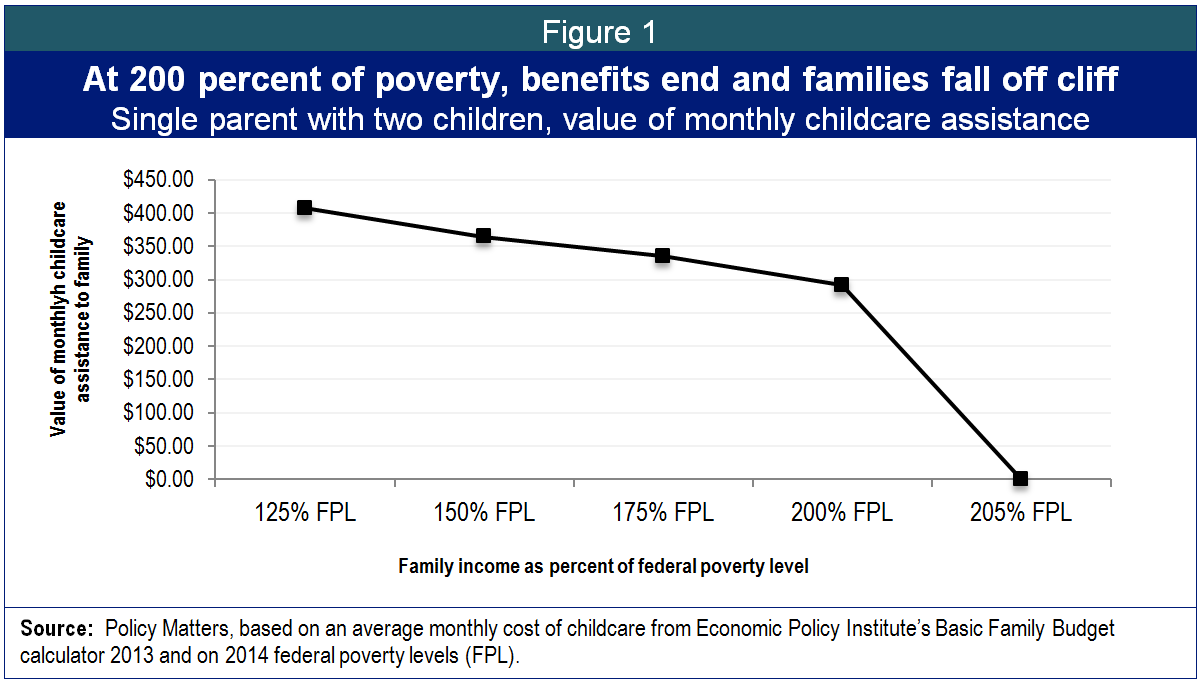

For families that enter the public childcare system at or under 125 percent of the federal poverty level, and have stayed in the system without interruption, earnings can increase up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level without loss of the work support. Family co-pays increase, but the work support keeps the share of income devoted to childcare to less than 9 percent of included earnings.[12] Over 200 percent of the federal poverty level, the work support ends. The family falls off the cliff as cost of childcare shoots up – from under 9 percent of income to over 17 percent of family income for the family portrayed here (Figure 1).

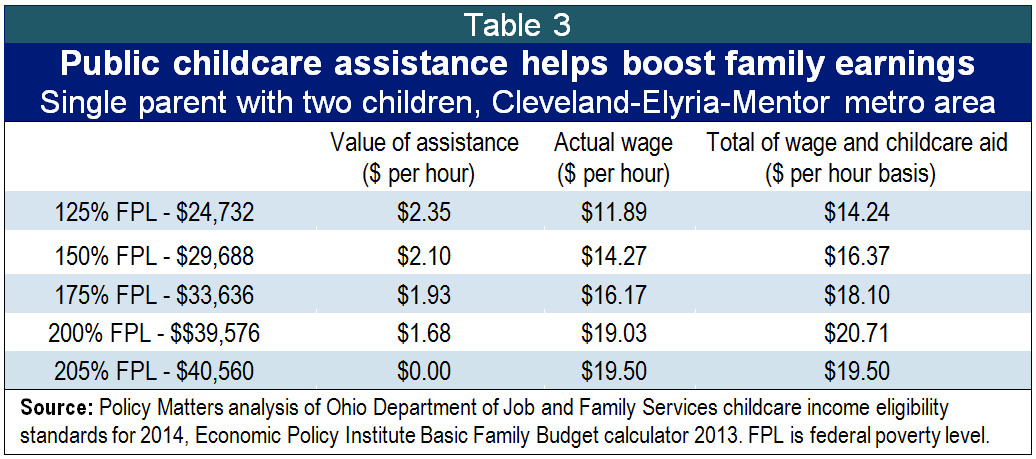

Another way of looking at this is by calculating the size of the pay raise needed to boost earnings without losing childcare assistance and damaging the family budget. While a family is getting childcare aid, Ohio’s many adjustments to the co-pay keep the share of childcare to less than 8.75 percent of total family income. Over 200 percent of poverty – say, at $19.50 per hour in the example in Table 3, below – the family is no longer eligible for the public childcare benefit. The unsubsidized cost of childcare rises from just under 9 percent of total income to 17.16 percent. A parent would need a raise of about 10 percent ($1.68 per hour) to avoid falling off the cliff and damaging family finances.

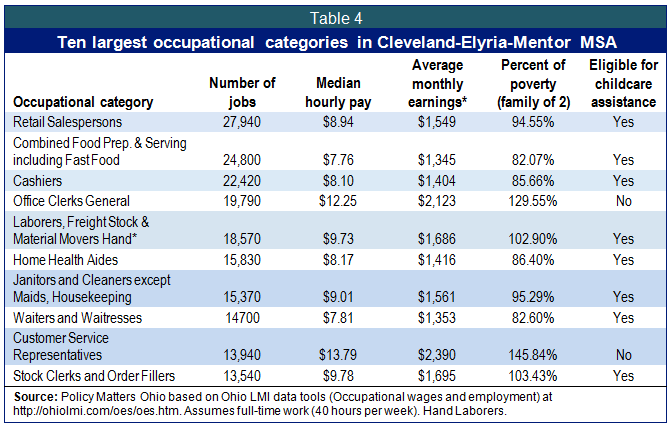

Too many jobs in Ohio, as in the rest of the country, have low pay: wages are not high enough for a family to cover its costs, particularly for costly elements, like childcare. Table 4 shows the 10 largest occupational categories in the Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor metropolitan statistical area in 2013. Median hourly wages are shown, along with whether earnings are likely to meet the threshold for initial eligibility for public childcare assistance.

Table 4 calculates an annual wage based on 40 weekly hours, traditionally considered full time work. The average number of hours worked weekly across all sectors and all jobs in Ohio is 34.1 hours. Many low-wage jobs offer fewer hours: in February 2014, the average hours per week for retail workers was 29.2. In health and social assistance jobs, it was 30.4.[13] Part-time work and low wages in some sectors are made worse by instability of jobs. Employee turnover is higher in retail than economy-wide, for example, averaging 56 percent annually as compared to 41 percent.[14]

Cracks in the childcare system

Most people who leave childcare assistance do not do so because their income rises above the maximum income ceiling.[15] According to the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, cases closed due to rising income levels accounts for a small minority of tracked reasons.[16] Leading reasons for closure among specifically named and tracked categories include failure to participate in required activities or non-use of services. This may reflect loss of jobs, seasonal change in class schedules, or changes in shifts and hours. According to the United States Department of Labor, change and variation in schedule is typical of low-wage occupations.

The childcare system requires notification for changes in status that impact eligibility, and the notification system itself can trip a family up. Changes that impact eligibility must be reported within 10 days. Required paperwork can include employer letters, pay stubs, and class schedules. Despite extremely limited family financial resources, penalties may accrue because of reporting mistakes. If there is an interruption in participation (a pink slip, illness, winter break), families can lose eligibility.[17] They can re-enter only at the threshold of eligibility, at the bottom of the income ladder: in the canyon.

The canyon

Figure 2 illustrates that after a separation in employment, a parent who tries to re-enter the labor market where she left off – say, at $12.86 per hour – actually brings home a lot less than that because she is above 125 percent of eligibility and can’t get her childcare assistance back. The cost of childcare – the equivalent of $2.22 per hour – knocks her disposable income back to the equivalent of $10.64 per hour. She does better starting again at 125 percent of eligibility, at $9.46 per hour, and getting back into the childcare assistance program. The problem is, she can’t advance in career or earnings by moving backwards.

The churning and bumpy nature of employment in low-wage sectors can too easily push families over the cliff or into a canyon. In Springfield, Ohio, Karen J. Lampe, President of Creative World of Childcare, Inc., sees a 30 percent monthly turnover in her classrooms, predominantly comprised of children supported by public childcare assistance. She attributes the turnover in part to program policies. “It is hard to become eligible and remain eligible,” she says.

When a family’s qualifying activity (work, training or school) ends, childcare eligibility continues without interruption if the parent has a new activity with a verified start date within 30 days. If there is not a verified activity – a new job has not been found; there is uncertainty around paying for next semester’s classes – money might be owed on the childcare, if nothing comes through. Yet if they do not use their childcare for 30 days, they lose their place in the system.

“Between 125 and 200 percent of poverty, a family is really poor,” says Director Lampe. “Parents bounce in and out of jobs, particularly because of illness.[18] They may be moving from relative to relative. Kids have so much instability in their lives. Our work support policies could do a better job in cushioning for kids.”

The context

Ohio’s economy doesn’t work well for low-earning families with young children. Childcare is expensive, aid ends at a level below self-sufficiency, and the largest, fastest growing occupational categories in Ohio are in low-wage sectors. The Economic Policy Institute’s Basic Family Budget calculator found childcare in 2013 took about 19 percent of the basic family budget at the level necessary to maintain a safe, decent, modest standard of living.[19] This level – the self-sufficiency level of income - is above 200 percent of poverty in many counties in Ohio. Depending on age of children and family size, it may be well above 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

Ohio’s economy doesn’t work well for low-earning families with young children. Childcare is expensive, aid ends at a level below self-sufficiency, and the largest, fastest growing occupational categories in Ohio are in low-wage sectors. The Economic Policy Institute’s Basic Family Budget calculator found childcare in 2013 took about 19 percent of the basic family budget at the level necessary to maintain a safe, decent, modest standard of living.[19] This level – the self-sufficiency level of income - is above 200 percent of poverty in many counties in Ohio. Depending on age of children and family size, it may be well above 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

Family income approaches self-sufficiency between about 200 and 280 percent of poverty in Ohio, depending on location and size of family. For example, a single mother with two kids – a school aged child and a preschooler – in Cuyahoga County, working full time, needs $23.20 an hour (248 percent of the federal poverty level for a family of three) to cover basic needs: housing, childcare, food, transportation, health care, household, miscellaneous, and taxes.[20] (This accounts for tax credits like the childcare tax credit, child tax credit and earned income tax credit.) If she has an infant and a preschooler, she needs to be making $26.01 per hour, because the cost of infant care is so high.[21]

Hourly wages in most of the 10 largest occupational groups in Ohio don’t make it close to self-sufficiency (Table 5). In fact, in only one of the state’s 10 largest occupational categories do the combined earnings of a two-child family with two parents working full-time (40 hours per week) at the occupation’s median wage earn enough to achieve self-sufficiency.[22] If these parents had hired on at entry-level wages in these jobs, and had worked without interruption up to the median, nine of 10 would still be eligible for public childcare assistance. If, however, there was an interruption, or they hired in above entry level, eligibility would have been limited.

Low-income employees often have unstable employment.[23] Childcare work supports are supposed to help stabilize employment, and inadequate or inconsistent supports make it hard to move into self-sufficiency. Research finds that the cliffs associated with means-tested benefits can diminish families' opportunities for upward mobility and control over their lives through work.[24] Difficulties parents and families experience are magnified by impact on the children.

Research shows that babies who experience multiple disruptions in early care are more likely to show aggression and be less outgoing in the preschool years.[25] Access to sensitive, responsive caregiving may be particularly protective for infants and toddlers growing up in families struggling with poverty and life stress; one in five children under age three who live in extreme poverty is estimated to face three or more risks to their development.[26]

“A child just begins to understand the flow of their day, to trust their teacher, after three months time,” says teacher Shawn Riggins of Columbus’s Southside Learning & Development Center. “Then they lose eligibility and move. Up to a third of the kids in our class churn in and out. It’s bad for those kids – they are traumatized; we know they have regressed, because sometimes we see them when they return. It’s bad for the class, because there are always new kids that are scared and disruptive.”

The impact on employers

In Ohio as in much of the country, the largest occupational categories are in low-wage sectors. Employers in these sectors can have significant numbers of workers with childcare assistance. Around the level of the cliff, some find it hard to move experienced workers into higher positions. Some employers struggle to find workers who can take periodic overtime or night hours. Qualified workers may not apply for promotions or may take themselves out of consideration because they fear losing childcare assistance.

When the state of Kentucky dropped the childcare assistance eligibility level, employers in Northern Kentucky started to worry about recruiting workers. Gateway Community and Technical College and a cluster of manufacturers worked with The Women’s Fund of The Greater Cincinnati Foundation to understand how to attract, retain and move workers up within their systems. Entry-level wages ranged from $12 to $14 per hour, so workers from the Ohio side of the river hit the earnings cliff quickly (a single mother with one child hits the ceiling at $14.32 per hour).

“Some employers thought they couldn’t find workers at mid-level positions because of a skills gap, but found it was something else,” explains Vanessa Freytag of the Women’s Fund. “It was the cliff. Workers couldn’t afford to take the next incremental raise, or to accept a promotion, because the increment in pay did not offset the loss of childcare aid. The parents could not risk losing the aid.”

Horseshoe Casino of Cincinnati has created a position to help their low-wage workforce navigate the system of work supports and other forms of aid. LeDawn Thomas, an employee relations specialist, is designing a program that will identify sources of help for workers in eight critical areas. The eight pillars in her “Breaking the Barriers” program will include information and referrals for problems in health, transportation, financial literacy, housing, utilities and other costs of living, including childcare.

“People have trouble with everything. They have trouble meeting their basic living expenses,” Thomas says. “Housing is at the top. Transportation is a big one. Childcare is too. When we see a problem in attendance or something that indicates someone is struggling, we intervene.”

Horseshoe, open 24 hours, seven days a week, runs three shifts. Employees bid for their preferred shift on a quarterly basis. Sometimes they get first shift, sometimes third. Not many providers in the Cincinnati area keep children overnight, so continuous eligibility can be lost with a shift change. Many positions at the casino pay close to the edge of eligibility, and workers must be vigilant on timely notifications of changes to eligibility, especially if they are between 24 hours a week (“part-time”) and 27 hours a week (“full-time”). Tipped work may push earnings over the limits and before a parent is fully aware of the cumulative impact.

“We lose people,” Thomas admits. “Not a lot – people do their best to make arrangements with family and friends, to keep track of their numbers, to stay in the system – or some system. But we lose some. Turnover is expensive. We work to keep people with us.”

Societal impact of good early care

The federal Childcare and Development Fund program, the major source of funding for most childcare assistance programs in the United States, was established as a part of welfare reform in the 1990s as a work support to help families out of poverty. The societal value of good and stable childcare was soon seen as a major ancillary benefit. A 2000 National Academies of Science report, Neurons to Neighborhoods, showed that brain development is most rapid during the first five years of life. Nurturing and stimulating care in the early years were found to build optimal brain architecture, fostering potential for learning. Hardship in early years can lead to later problems.[27] Other studies have demonstrated that the benefits of childcare last well into adolescence.[28] Interruptions in care reduce benefits for individual children, with a long-term societal impact.

The federal Childcare and Development Fund program, the major source of funding for most childcare assistance programs in the United States, was established as a part of welfare reform in the 1990s as a work support to help families out of poverty. The societal value of good and stable childcare was soon seen as a major ancillary benefit. A 2000 National Academies of Science report, Neurons to Neighborhoods, showed that brain development is most rapid during the first five years of life. Nurturing and stimulating care in the early years were found to build optimal brain architecture, fostering potential for learning. Hardship in early years can lead to later problems.[27] Other studies have demonstrated that the benefits of childcare last well into adolescence.[28] Interruptions in care reduce benefits for individual children, with a long-term societal impact.

The business community and economists recognize the societal and economic value of early childhood education.[29] Professor James J. Heckman of the University of Chicago is a leading advocate for increased investment in young children as a way of lowering long-term societal costs.[30]

Increasingly, jobs with a living wage require literacy and numeracy. For workers to earn a living, and for employers to have the workforce they need, a literate workforce is essential. Early childhood education can increase essential skills basic to tomorrow’s workforce, like literacy. Lack of solid educational foundation is already a problem in some sectors. For example, the U.S. military has found that many recruits have educational deficits and has consequently advocated early childhood education.[31]

Impact on childcare infrastructure

Churning among clients in the public childcare assistance program creates problems for providers.

“My teachers are so busy integrating new kids into the classroom there is no time for teaching,” says Karen J. Lampe of Creative World of Childcare, Inc. “All your time is spent building the platform of trust needed to teach and learn.”

Columbus’s Southside Learning & Development Center, like other centers, helps parents fill out the lengthy application and other forms. They fax it to the county office so there is a receipt. A rejection of an application may come after 30 days, and the entire application must be done over. If the provider accepted the client under the current system, the lengthy approval may be a cost factor. “From the provider perspective, it’s a nightmare,” says Roberta Bishop, Southside’s executive director. “We elect to help. Between 20 to 25 percent of the families we serve are constantly moving. They may lose their pay stub. They may not have gotten a notice, and they don’t know what documents they need. We can help them keep order, stay on top of the requirements.”

Southside is a United Way agency. Up to a third of the families they serve need case management services. “I stay on top of their notification needs,” says Amy Valentine, fiscal operations director. “I accompany them to hearings. I keep a file on each family, and my files are in order. We have positive outcomes in many hearings.”

Southside is a United Way agency. Up to a third of the families they serve need case management services. “I stay on top of their notification needs,” says Amy Valentine, fiscal operations director. “I accompany them to hearings. I keep a file on each family, and my files are in order. We have positive outcomes in many hearings.”

The case management function – the work providers do to help families keep from falling between the cracks – is not funded by the program. The contract between the state and the provider states that the provider will assist clients, but level of help and communications protocol with the county are not specified. Providers point out that this is especially difficult given that payments for public childcare have been reduced: from 35 percent of the 2008 market survey to 21 percent of the 2012 market survey in FY 2012-13,[32] to 16 percent of the market survey in the current year.[33]

“Our funding model no longer works for the agency,” Director Bishop says. “We have to apply for more and more grants.”

Costs associated with childcare assistance cause some centers to curtail slots for the public childcare assistance students. The 30-day approval period can be a risk and cost factor. A parent has taken a job and needs childcare, but the state aid may not be approved for 30 days. The center takes a risk if they accept the child prior to approval. Many centers simply don’t take that chance, even though Director Bishop says the risk is low; in her experience, less than 2 percent turn out to have problems. Another cost has to do with the limited number of absences allowed over six months. Many infants and children need more than the 10 absent days allotted per six-months, but the state will not cover more. Lori O’Hara of North Broadway Children’s Center in Columbus points out that her center does not get paid if a child is out for more than 10 days, but they do not want sick kids brought to school. “That is where we lose money,” she says. “We have one public childcare slot. We used to have three, but we could not plan for the days the kids missed and we couldn’t subsidize those slots.”

The North Broadway Children’s Center is in Clintonville, a Columbus neighborhood where demand is high but incomes vary broadly. “I know many families who have childcare vouchers would like to get in here, because of the high quality care we can offer” says O’Hara. “We’d like to have more, because it would be a service to the community, but we can’t afford it.”

Conclusion and recommendations

Access to consistent, quality childcare is essential to children, families, communities, and our economy. Yet today’s economy has far too many low-wage jobs that leave families unable to access high-quality childcare. With these low wages, everyone has to work, including both parents and other family members who might once have assisted with childcare. Public policy needs to support low-wage working families in a way that contributes to stability and supports early learning.

Access to consistent, quality childcare is essential to children, families, communities, and our economy. Yet today’s economy has far too many low-wage jobs that leave families unable to access high-quality childcare. With these low wages, everyone has to work, including both parents and other family members who might once have assisted with childcare. Public policy needs to support low-wage working families in a way that contributes to stability and supports early learning.

Ohio’s public childcare assistance program has good features. There is not a waiting list for services. Share of family income required for childcare under Ohio’s public childcare assistance program is at about the level recommended by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.[34] Improvements are needed, however; some are already in process.

Increase the income ceiling. To reduce the earnings cliff, the income ceiling should be extended to the self-sufficiency level by family size and county of residence. Share of family income required for childcare up to 200 percent of poverty should be maintained at current levels. For levels between 200 percent of poverty and self-sufficiency, assistance should be tapered so that the cliff at the end is not so steep.

Accept children for 12 months at a time regardless of changes in family income or employment. This allows children to stay in one center, to build a platform of trust and to start learning. It helps pressed caseworkers, eases financial and other stress of parents, and helps teachers stabilize a classroom for sustained learning.

Childcare stakeholders have asked that the public childcare program include 12 months of continuous eligibility. This would match the structure already in place in Ohio’s early learning program, often used in coordination with the public childcare assistance program. An amendment to House Bill 483 provides for 13 weeks of continuous eligibility out of the year, during which a worker may lose one job but get a new one, or graduate from college and find a job, or bounce into third shift and back into first; during this time, the kids get to stay in their childcare class, without interruption. Only one such period is allowed within the year.

This is a good start, but still allows too much disruption in the care and education of too many children in families where low-wage jobs churn and new jobs take a long time to find in a sluggish economy. Twelve months of consistent childcare should be guaranteed to help stabilize the lives of children and families.

Allow childcare providers to presume eligibility for public childcare assistance. Under Ohio law, approval for childcare assistance may take 30 days – but the parent needs the care, and the center needs the customer. Another amendment to HB 483 provides for “Presumptive Eligibility.” The risk of whether the state will approve the applicant, and the timeliness of such approval, has been borne by the provider. The “Presumptive eligibility” language fixes this, allowing children to get care more quickly, helping parents get and keep jobs, and reducing provider concerns.

Allow childcare providers to presume eligibility for public childcare assistance. Under Ohio law, approval for childcare assistance may take 30 days – but the parent needs the care, and the center needs the customer. Another amendment to HB 483 provides for “Presumptive Eligibility.” The risk of whether the state will approve the applicant, and the timeliness of such approval, has been borne by the provider. The “Presumptive eligibility” language fixes this, allowing children to get care more quickly, helping parents get and keep jobs, and reducing provider concerns.

Increase the income level for initial eligibility. Let families qualify for assistance until they earn enough to be self-sufficient. That way, if a parent changes jobs, shifts, or has illness, she can hire back in at a level where she left off.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to St. Luke’s Foundation and Christie Manning for support. We also thank: Roberta Bishop, Marika Douglas, Debbie Fodge, Vanessa Freytag, Margaret Hulbert, Katie Kelly, Eric Karolak, Karen Lampe, Stephanie Moore, Shawn Riggins, LeDawn Thomas, and Amy Valentine. Amanda Woodrum of the Policy Matters staff assisted with interviews and writing.

[1] See Katie Kelly and Susan Blasko, “Early Childhood Challenges and Opportunities,” State Budgeting Matters, Page 3, Table 1, February 2011 at http://bit.ly/1fey8mv.

[2] Ohio Department of Job and Family Services (ODJFS), Childcare and Development Fund Plan for Ohio, FFY 2014-15, Section 1.2.1 (p.4), at http://1.usa.gov/QLEgY6; also e-mailed communications from ODJFS, April 24, 2014. Agency line items funding public childcare include 600617 (day care federal); 600689 (TANF federal); 600413 (childcare state match for Childcare Block Grant) and 600535 (early care and education state match for TANF). Early Care and Education is a separate program that serves less than 10,000 children, although the two programs are used in tandem.

[3] Ohio numbers calculated from the 2012 American Community Survey based on children under the age of 11 and in families under 185 percent of poverty. National estimates are from the United States Government Accountability Office (2010,May5). GAO-10-344. “Childcare: Multiple factors could have contributed to the recent decline in the number of children whose families receive subsidies,” at http://www.gao.gov/assets/310/304093.html.

[4] Emailed communications from Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, April 8, 2014.

[5] Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, “Childcare weekly co-payment desk aid,” http://bit.ly/1nN6uwH.

[6] Childcare and Development Fund (CCDF) Plan For Ohio FFY 2014-15, p.65 at http://1.usa.gov/QLEgY6.

[7] Linda Laughlin, “Who’s minding the kids? Childcare arrangements in Spring 2011,” United States Department of Census, April 3, 2013 at http://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/p70-135.pdf.

[8] In state fiscal year 2013, 105,342 children were in public childcare assistance. The initial eligibility level for public childcare assistance is 125% of federal poverty level. If a parent has transitioned from TANF/Cash Assistance (Ohio Works First or “OWF”) in the last 12 months, the eligibility threshold (“transitional eligibility”) is 150 percent of FPL. In fiscal year 2013, 10,817 children were part of the OWF childcare. Public Assistance Statistics Monthly of the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services at http://jfs.ohio.gov/pams/Reports/PAMS-SFY2013.stml.

[9] See Katie Kelly, Op. Cit.; see also Ohio Legislative Service Commission www.lsc.state.oh.us/budget/mainbudget.htm, Red Books and Green Books for Ohio Department of Job and Family Services current and past General Assemblies.

[10] Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Redbook for the biennial budget of the 129th General Assembly (HB 153).

[11] National Center for Children in Poverty, State Profile at http://bit.ly/VmH6Rg. See National Women’s Law Center, “Pivot Point: State Childcare Assistance Policies 2013,” http://bit.ly/1rrqyFj.

[12] “Family co-payments range from zero to 8.75 percent of a family’s gross monthly income. Ohio Revised Code specifies that no copayments can exceed ten percent of the family’s income.” Childcare and Development Fund (CCDF) Plan For Ohio FFY 2014-15, p.70 at http://1.usa.gov/QLEgY6.

[13] Ohio Labor Market Review, Hours and Earnings of Production or Nonsupervisory Workers (Not Seasonally Adjusted) for Ohio and Metropolitan Statistical Areas, p.39, http://ohiolmi.com/ces/LMR.pdf

[14] Françoise Carré, Ph.D. and Chris Tilly, Ph.D., Continuity and Change in Low-wage Work in U.S. Retail Trade, Center for Social Policy, University of Massachusetts, April 2008 at http://bit.ly/1kOECWZ.

[15] Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, e-mailed data, “eligibility closures 2013_3.xls,” April 14, 2014.

[16] Id.; According to the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, about 55 percent of public childcare assistance case closures are tracked to two categories: “Automated” and “Administrative.” These categories are described as annual or “clean-up” categories. Percentages reported here are taken as a share of the remainder in categories other than ‘automated’ or ‘administrative.’ About 4 percent of tracked case closures other than administrative or automated are due to income rising above the income ceiling. About 60 percent – divided roughly equally - are due to either failure to be in required activities or failure to use the service.

[17] Parents receiving childcare assistance can continue to receive it for up to 30 days if there is a change in work or school activities such that they are scheduled to return to work, school, or training within that timeframe. In addition, parents who lose their job can continue to receive childcare assistance for a 15-day prior notice period; if the parent starts another approved activity within that period, the parent can remain eligible – with proper notification and documentation of the change. National Women’s Law Center, “Pivot Point, State Childcare Assistance Policies 2013” at http://bit.ly/1p1qs83.

[18] The hard choices parents face are presented in this piece by Randy Albelda and Jennifer Shea, “To work more or not to work more: Difficult Choices, Complex Decisions for Low-Wage Parents,” Journal of Poverty, July 20, 2010 at http://bit.ly/1kNFPww.

[19] EPI’s Family Budget Calculator (http://www.epi.org/resources/budget/) measures the income a family needs in order to attain a secure yet modest living standard by estimating community-specific costs of housing, food, childcare, transportation, health care, other necessities, and taxes. The budgets, updated for 2013, are calculated for 615 U.S. communities and six family types (either one or two parents with one, two, or three children). As compared with official poverty thresholds such as the federal poverty line and Supplemental Poverty Measure, EPI’s family budgets offer a higher degree of geographic customization and provide a more accurate measure of economic security. In all cases, they show families need more than twice the amount of the federal poverty line to get by.

[20] Ohio Association of Community Action Programs, Self Sufficiency Standard for Ohio 2013, “Table 18. The Self-Sufficiency Standard for Cuyahoga County,” p.67 at http://www.selfsufficiencystandard.org/docs/OH13SSS_web.pdf

[21] Id.

[22] This is for all metropolitan statistical areas and rural areas in Ohio, calculated using the EPI Basic Family Budget Calculator at http://www.epi.org/resources/budget/.

[23] According to the profile of Ohio compiled by Columbia University’s National Center for Children in Poverty, the majority (58 percent) of children in low-income families lived with a single parent. Fewer than half (43 percent) have a parent with full time employment, compared to 90 percent of kids in homes with incomes over 200 percent of poverty. More than a third have parents who are employed part-year or part-time. Columbia University, National Center for Children in Poverty, Profile of the State of Ohio for 2011 at www.nccp.org/profiles/state_profile.php?state=OH&id=6.

[24] Romich, J. L. (2006). Difficult calculations: Low-income workers and marginal tax rates. Social Service Review, 80, 27–66.

[25] Patten, Peggy. (2001). “Teacher- Child Relationships Are Central to Quality.” Parent News [Online], 7(2) at http://npin.org/pnews/2001/pnew301/int301c.html.

[26] Knitzer, Jane and Jill Lefkowitz, “Helping the Most Vulnerable Infants, Toddlers, and Their Families,” January 2006, Columbia University, National Center for Children in Poverty, http://www.nccp.org/publications/pub_669.html.

[27] Jack P. Shonkoff and Deborah A. Phillips, Editors, “From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development,” National Research Council Institute of Medicine, from National Academies Press at http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=9824.

[28] Deborah Lowe Vandell, Jay Belsky, Margaret Burchinal, Nathan Vandergrift, and Laurence Steinberg, “Do Effects of Early Childcare Extend to Age 15 Years? Results From the NICHD Study of Early Childcare and Youth Development,” NICHD Early Childcare Research Network, May 1, 2011, National Institute of Health Public Access site at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2938040/.

[29] Steffanie Clothier and Julie Poppe, Early Education as an economic investment, National Council of State Legislatures at www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/new-research-early-education-as-economic-investme.aspx.

[30] Brendan Greeley, “The Heckman Equation: Early Childhood Education Benefits All,” Bloomberg Business Week, Jan. 16, 2014 at www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-01-16/the-heckman-equation-early-childhood-education-benefits-all.

[31] “Fully 75 percent of 18-year-olds are not qualified to serve their country through military service. To address this national security issue, military leaders have identified the need for quality early care and education for all children as a top priority to ensure children get off to the right start.” From “The High Cost of Childcare: 2013 Report. Childcare Aware of America” at http://usa.childcareaware.org/sites/default/files/cost_of_care_2013_103113_0.pdf .

[32] Savings of around $41 million annually were anticipated as a result of the cuts in eligibility and provider payments in the public childcare program in HB 153, the budget for FY 2012-2013. Together with the reduction in eligibility, state cuts to public childcare assistance have been in the neighborhood of $50 million annually since FY 2012. Based on anticipated savings outlined in the Redbook for Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, 129th General Assembly budget bill, Ohio Legislative Service Commission at http://www.lsc.state.oh.us/fiscal/redbooks129/jfs.pdf.

[33] Childcare and Development Fund (CCDF) Plan For Ohio FFY 2014-15, Op.Cit, p.65at http://1.usa.gov/QLEgY6.

[34] National Child Care Information and Technical Assistance Center. (2008). “Childcare and Development Fund: Report of state and territory plans: FY 2008-2009,” Section 3.5.5 – Affordable co-payments, p. 89.

Tags

2014Budget PolicyChild careWendy PattonPhoto Gallery

1 of 22