Overview: Ohio's 2014-15 Budget

October 03, 2013

Overview: Ohio's 2014-15 Budget

October 03, 2013

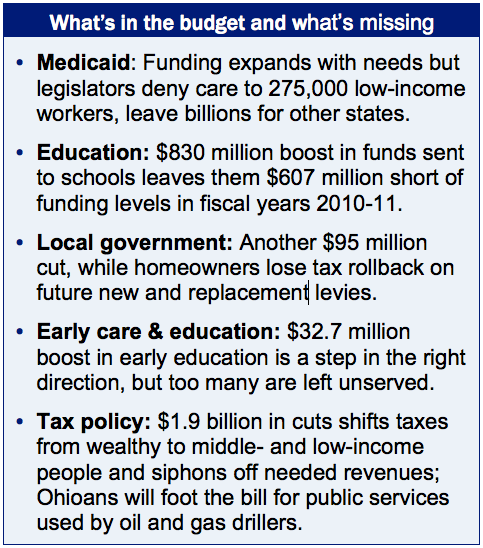

Download summary (2 pp)Download full report (27 pp)Press releaseThe new state budget increases the General Revenue Fund by $4.5 billion over two years, but did not restore key investments to 2010-11 levels. The budget also cut taxes by $1.9 billion, shifting taxation from the affluent to those with less income and making it harder to adequately fund critical services.

The state budget for the next two fiscal years restores some necessary investments in Ohio after very deep cuts in the prior biennium. But legislators missed essential opportunities. They failed to expand Medicaid, which would have provided health care to hundreds of thousands, made people healthier, and brought billions of federal dollars into the state. They boosted educational spending compared to the steep cuts in 2012-13, but many public schools will get less because more money will go to poorly regulated charter schools. They failed to modernize the tax structure for the growing oil and gas industry and gave significant tax cuts to the wealthiest and business owners, which will make it harder to fund the education and infrastructure needed for real success.

The state budget for the next two fiscal years restores some necessary investments in Ohio after very deep cuts in the prior biennium. But legislators missed essential opportunities. They failed to expand Medicaid, which would have provided health care to hundreds of thousands, made people healthier, and brought billions of federal dollars into the state. They boosted educational spending compared to the steep cuts in 2012-13, but many public schools will get less because more money will go to poorly regulated charter schools. They failed to modernize the tax structure for the growing oil and gas industry and gave significant tax cuts to the wealthiest and business owners, which will make it harder to fund the education and infrastructure needed for real success.

Ohio budgets on a biennial basis: each budget provides funding for a two-year period. This report examines the new, two-year (“biennial”) budget for fiscal years 2014 and 2015, and compares it with the last two-year budget. Ohio’s new budget will total $121.1 billion. The appropriations authorized in this budget are 12 percent or $14.8 billion larger than in the prior budget, fiscal years 2012-13.

Budget analysis typically focuses on the General Revenue Fund (GRF) because state tax revenues fund it. Ohio also includes some federal dollars in the GRF, something most states do not do. When federal dollars are removed, state-only GRF revenues make up just over a third – 36 percent – of the total budget. The state-only share of the GRF increased by almost $4.5 billion, 11.4 percent over state-only share of GRF in the budget for fiscal years 2012-13.[1] Increases in GRF represent growth in funding for health care for poor children and some very low-income parents, as well as low-income people who are aged, blind and/or disabled. In addition, funding for education increased in the state budget for fiscal years 2014-15 compared with 2012-13, although major funding cuts in the last budget were not completely restored.

There were also cuts in this budget. For example, local government faces $95 million in cuts to revenue sharing, following cuts of a billion dollars in the last biennium. The impact is felt in counties, cities, villages, townships, and various services – children services, senior services, mental health services – funded by local property tax levies.

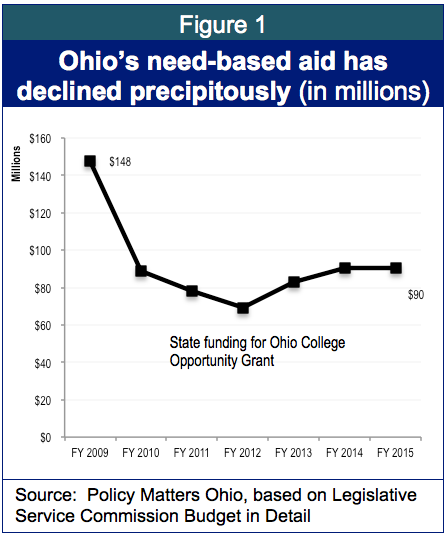

Although the budget will grow in fiscal years 2014-15 compared to the very austere 2012-13 budget, many important areas have been underfunded for so long that services remain insufficient. The waiting list for services to those with developmental disabilities is 30,000.[2] The Ohio College Opportunity Grant remains far behind the funding levels prior to the recession. And long-term, unaddressed needs remain. For instance, Ohio owes more than $1.5 billion to the federal government because we’ve borrowed to pay for unemployment compensation. Although the General Assembly set aside $120 million over the two-year period to pay interest costs for this, legislators have not come up with a plan to make the fund solvent and prepare for an increase in claims.[3]

Sources of funds in the new state budget

This GRF budget is larger than the last budget for several reasons. First, the state reduced what it previously provided to local governments, schools and libraries. This along with other tax changes included in the 2012-13 budget bill brought $1.3 billion to the General Revenue Fund that it had not had in prior years.[4] Second, strong personal income tax collections came in at $824.2 million over estimates.[5] This was partly the result of the country coming out of the recession and partly the result of changes in federal tax rates that caused some wealthy taxpayers to report earnings early. Finally, the state received a one-time payment of $495.5 million[6] because Ohio finished leasing the revenue stream from wholesale liquor sales to support the new, privatized economic development agency, JobsOhio.[7] Altogether, there was a year-end surplus of $2.084 billion, from which the state’s rainy day fund was replenished [8] and $517.3 million in tax revenues from the last biennium were moved forward for use in the current biennium.[9]

Tax changes

The General Assembly reduced personal income tax rates and created a new tax break for business owners that will siphon off billions of dollars in revenue over the next few years, revenue that is badly needed to restore local services, put teachers back in Ohio’s classrooms, control tuition at state colleges, and provide human services that a lagging economy and growing inequality have made all the more important. The legislature paid for these tax cuts in part by using revenue available based on growth the state expects over the next two years, and in part by raising other taxes, including the sales tax.[10] The net result is a further shift in who pays Ohio’s taxes, so that affluent residents on average pay thousands of dollars a year less, middle-income Ohioans see tax cuts that can’t cover a tank of gas, and some of Ohio’s poorest residents pay more than they have in the past.

As with other areas of the budget, tax policy changes were also notable for what they did not do. The General Assembly refused to go along with Gov. Kasich’s proposal to broaden the sales tax to cover most services. Instead of doing that and using some of the revenue to reduce the sales-tax rate, legislators raised the sales-tax rate. This is a losing battle long-term; as services have come to make up more of consumer purchases, broadening the tax to include more of them is more sensible than raising the rate on a shrinking share of the economy.[11] The legislature also failed to increase the tax on oil and gas drilling to put Ohio more in line with other energy-producing states. State policy, as a result, allows precious, limited natural resources to be extracted and fails to help the communities that face higher infrastructure and other public service costs because of the drilling activity.[12]

Nor did the General Assembly create a mechanism to review Ohio’s $7.7 billion in annual tax exemptions, credits and deductions, known as tax expenditures. Indeed, while some tax expenditures were eliminated, such as one for gambling losses, more new ones were created than old ones repealed.[13] Tax breaks were created or expanded for-profit grain handlers, certain fraternal organizations, purchases of computer data center equipment, veterans’ organizations, and large employers, among others. Overall, the cost of such expenditures will rise by hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

This is largely from one new exemption for business income, which will cost more than half a billion dollars a year. Overnight, this will become the third-largest tax break in the state tax code. This new tax break is unlikely to generate new jobs.[14] The bulk of Ohio business owners eligible for the break employ no one but themselves. Although the break costs the state, most owners get no more than a few hundred dollars a year, and at maximum, less than $7,000, not enough to add an employee.

The General Assembly cut state income-tax rates by 10 percent, increasing to that percentage over a three-year period. According to OBM, this will cost almost $2.28 billion over the next two years. In addition, OBM expects the new exemption for business income to reduce state revenue by $1.09 billion over that time span.[15]

The rate cut does little for most Ohioans in part because, like most states, we have a graduated income tax, under which rates go up as income goes up. The bulk of the modest income-tax savings that most Ohioans will see from the rate cuts will be wiped out by other tax increases (see below). And some Ohioans won’t see an income-tax cut. According to the Ohio Department of Taxation, 81 percent of Ohio taxpayers will see an income-tax cut because of the income-tax changes, 17 percent will see no change (a preponderance of whom pay no income tax now), and 2 percent will see a slight increase.[16]

Many Ohioans are seeing no benefit from the income-tax cuts, and some are seeing a tax increase. In part, this is because state law says that those with incomes of $10,000 and below receive a credit that wipes out their income-tax liability. Other exemptions and credits, such as the $1,700 personal exemption for each filer and their dependents and the $20 credit, mean that some Ohioans with incomes higher than $10,000 also are among those who don’t have income-tax obligations.[17] Despite these provisions of the tax code, low-income Ohioans on average pay considerably more of their income in overall state and local taxes than those high up on the income scale.[18] Some don’t pay income tax, but as a group they more than make up for that with sales, property and other taxes they pay. Meanwhile, other provisions in the budget bill (see below) will limit credits and exemptions. Some Ohioans will actually pay more income tax because they are affected by those limitations.

Who Pays?

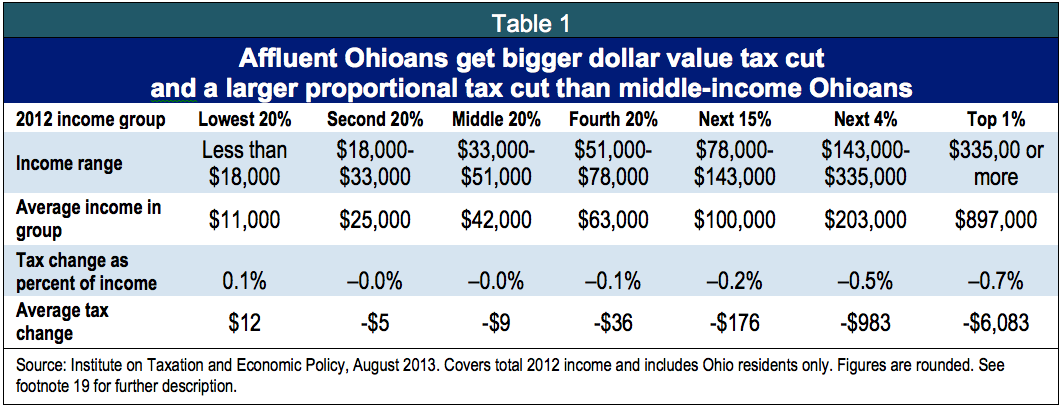

According to an analysis done for Policy Matters Ohio by the Institute on Taxation and Economy Policy, the poorest fifth of Ohioans, who last year made less than $18,000, on average will see a $12 tax increase because of the changes in House Bill 59.[19] The middle fifth of taxpayers, who earned between $33,000 and $51,000, will see a $9 cut, while the top 1 percent, who made more than $335,000 apiece, will average a tax cut of $6,083.

Affluent Ohioans get both a bigger dollar value tax cut and a larger proportional tax cut than middle-income Ohioans; the top 1 percent will see an average reduction of 0.7 percent of their income while middle-income earners get a cut so small that it doesn’t even average 0.1 percent of their income.

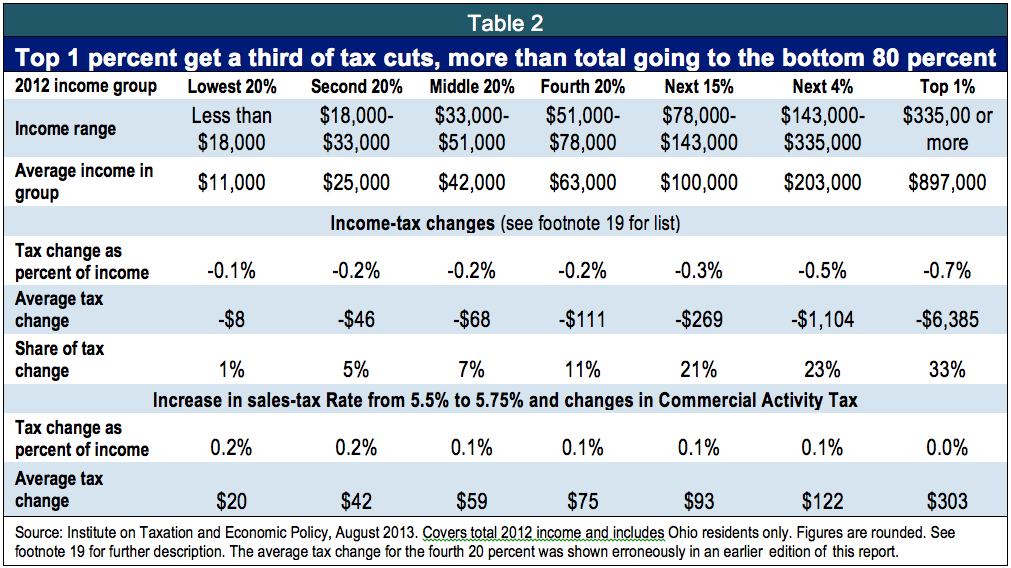

ITEP’s analysis breaks out the effects of the income-tax changes from the ¼-penny increase in the state sales tax and increase in the minimums many businesses will pay under the main state business tax, the Commercial Activity Tax. It shows that the top 1 percent will get nearly a third of the income-tax cuts, more than the total going to the bottom four-fifths of taxpayers. Meanwhile, the sales-tax increase falls more heavily on low- and middle-income taxpayers, who spend more of their income than upper-income taxpayers do (the effect of the Commercial Activity Tax increase is included with the sales tax because it is likely to ultimately fall on individual taxpayers in much the same way). On average, middle-income taxpayers will see a $68 annual cut in income tax, but this will nearly be erased by the sales and CAT tax changes, leaving an overall cut averaging just $9. Similarly, the bottom income group, those earning under $18,000 last year, will see an average $8 benefit from the income-tax changes, but this will be more than wiped out by the sales and CAT tax changes. Table 2 shows how taxpayers in different income groups will be affected by income, sales and CAT tax changes.

Included in the table above is a new state Earned Income Tax Credit, which will allow some of those who qualify for the federal EITC to receive a 5 percent credit on their Ohio income tax. This smart policy takes a step toward correcting a state and local tax code that requires low-income families to pay a larger share of their income than the affluent.[20] The federal EITC does more than any other program to keep working families out of poverty, and Ohio now joins two dozen other states with their own credits.[21] However, as the data above show, the new state EITC is insufficient to make the tax changes even a break-even proposition for many poor Ohioans. Indeed, many of the poorest Ohioans will be unable to qualify for the credit. The credit is not refundable, meaning that even though low-income Ohioans on average pay more of their income in all taxes combined than affluent Ohioans do, they won’t qualify if they aren’t paying income tax. It also is limited so that those earning more than $20,000 will only be able to receive a credit towards half of their taxable income. Nevertheless, the credit is a small step forward.

The General Assembly approved numerous other tax changes in the final bill, many added by the conference committee at the end of the budget process with virtually no public input. This potpourri included measures aimed at raising revenue to support a larger income-tax rate cut and the business-income tax exemption; while the sales-tax increase was the biggest and most visible, all of the other tax changes actually will produce slightly more revenue each year, according to administration estimates. Among these were changes in income-tax exemptions and credits, including:

- A three-year freeze in the personal exemption, which is indexed to inflation and deducted from income when taxpayers figure their income tax. The administration estimated this would save the state $17 million in fiscal year 2014 and $34 million in 2015.

- Freezing for three years the indexing of income-tax brackets, which has kept taxpayers from moving into higher brackets because of growth in their income that merely matches inflation. This is estimated to raise $37 million in fiscal year 2014 and $90 million in 2015.

- Means-testing the $20 credit that taxpayers receive for themselves and each dependent, so only those with Ohio taxable income under $30,000 are eligible. This is estimated to save the state $125 million in both years.

The General Assembly also ended certain state reimbursements to schools and local governments for two “rollback” mechanisms that effectively pay 10 percent and 2.5 percent, respectively, of homeowners’ property taxes (the 10 percent rollback covers all residential property owners, while the 2.5 percent rollback covers only owners who live in their homes). The state will continue reimbursing for existing levies, but not for new or replacement levies. OBM has estimated this will save the state $34 million in in fiscal year 2015 and $96 million in 2016. The change is likely to make it more difficult for local governments and school districts to win approval of new property-tax levies and is an additional example of the state reducing support to localities.

Juni Johnson-Frey, executive director of Paint Valley Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services Board, responded to this change in recent testimony to a state House committee. “We are concerned that homeowners will be less inclined to pass a levy once they understand they will now have to pay the full rate of 100 percent as opposed to the 87.5 percent they paid in the past,” Johnson-Frey said. “Right now, for those communities already feeling negatively toward levies, this increase will make it harder.”[22]

Some of the revenue-raising measures were well targeted, raising revenue from those who can afford it or expanding the tax base. For instance, the General Assembly:

- Added a progressive element to the Commercial Activity Tax, the tax on Ohio receipts that is now the state’s main general business tax. The General Assembly increased the minimum tax based on the amount of gross receipts. For instance, instead of paying the flat $150 all businesses have paid on the first $1 million in receipts, a company with annual receipts of more than $4 million will pay $2,600. This is expected to generate $86 million in fiscal year 2014 and slightly more in ensuing years.

- Means-tested the homestead exemption on local property taxes. Created to help low-income seniors, the homestead exemption was expanded during the Strickland administration to cover all homeowners over 65. It eliminates tax liability on the first $25,000 in home value. Some $400 million in such exemptions were distributed during calendar 2012.[23] The General Assembly, while keeping the exemption for those receiving it now, scaled it back so that those who turn 65 after the end of 2013 will only be eligible if income is less than $30,000, as computed for state income-tax purposes.[24] The administration estimated this would save the state $9 million in fiscal year 2015 and $27 million in 2016. The change makes sense, but it should apply to all seniors, so wealthy homeowners don’t continue to receive an unneeded tax break when less affluent property owners just turning 65 now are excluded. The means testing could also be improved.[25]

- Extended the sales tax to digital goods and services, such as video and music downloads, bringing in an estimated $15 million a year. This is a step toward bringing the sales tax into the 21st century, so e-books and other such products are treated as physical counterparts are.

- Raised the tax on little cigars to 37 percent of the wholesale price, so that percentage is equivalent to the cigarette tax.

The General Assembly also carved a new tax out of the CAT covering motor fuel, which will be paid once instead of each time motor fuel is sold, at a rate of 0.65 percent. This came in response to an Ohio Supreme Court decision that CAT tax receipts had to be used for highway purposes. The taxation department has estimated that this tax will generate $125 million in fiscal year 2015, when it becomes effective, and more than $170 million in both 2016 and 2017.[26] We should monitor how much the new tax generates compared to these estimates.

In summary, the tax changes in this year’s budget bill were substantial and far-reaching. Some, such as the earned income tax credit, means-testing the homestead exemption and applying the sales tax to digital goods and services, brought Ohio’s tax code more in step with today’s economy and provided a degree of fairness. But the biggest elements of the package – the income-tax cuts, the sales-tax increase and the business-income exemption – overwhelm these smaller elements. The tax cuts will make it harder than ever for Ohio to educate our children, care for each other and offer the services and amenities that make our state attractive to residents and businesses. The overall effect of the tax package is to further shift taxes from affluent Ohioans to those with less income.

Supporters claim these cuts will make Ohio more attractive to business and will generate jobs. The evidence from our own recent history does not support that – since June 2005, when major Ohio tax cuts were approved, Ohio has lost more than 214,000 jobs, or 3.96 percent of its total, while the nation as a whole has gained 2.48 million, or 1.86 percent. Gov. Kasich’s budget is based on a forecast that job growth that will continue to lag the national average during fiscal years 2014-15.[27]

Tax cuts also are risky. As long as revenues come in as expected, the tax cuts over the next two years will be paid for. But should revenues dip, tax cuts can become dangerous. That’s what happened after the big tax cuts of 2005: The deep 2007-09 recession, on top of the tax cuts themselves, slashed revenues and created a fiscal crisis. Ohio’s GRF taxes fell by more than $3 billion a year between fiscal years 2008 and 2010. Leaving aside the effects of inflation, they did not return to 2006 levels until 2013 – and even that was partly because the state seized revenues that had previously gone to schools and local governments. Ohio is badly in need of an antidote to its tax-cut fever.

Use of funds in the new state budget

In this section, we look at specific programs within three broad categories of public service. We provide an overview of the state’s investment in education, its contribution to thriving communities, and how the state promotes a healthy environment and healthy people.

Investment in education

Funding for all education – K-12, higher education and early learning – increased in the state budget for fiscal years 2014-15 compared with the deep cuts of 2012-13. Funding has not been restored to earlier levels.

Primary and secondary education

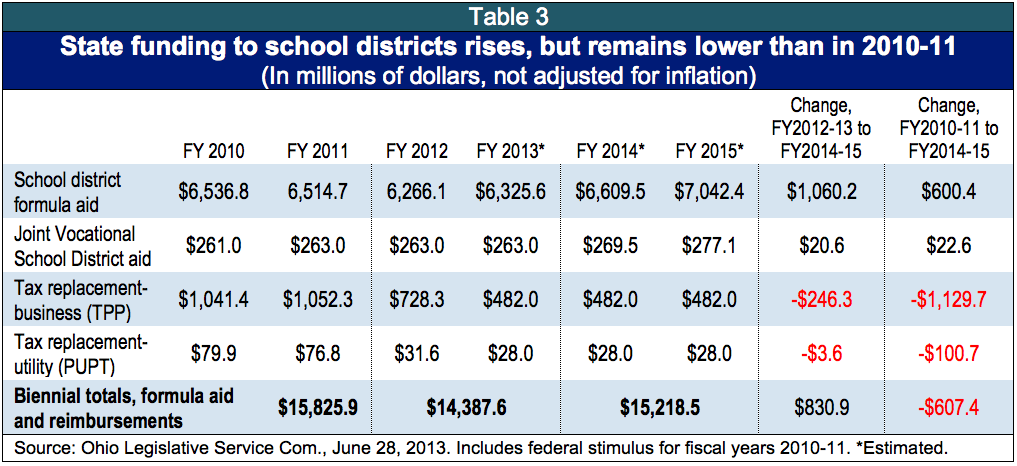

The new budget increases state investment in K-12 education but does not make up for deep cuts in the last budget. State funding sent directly to school districts increases by $830 million in fiscal years 2014-15 compared with 2012-13 but remains $607 million below what it was in fiscal years 2010-11. This includes formula funding and tax reimbursements, a mix of GRF and non-GRF funds. It also includes some federal funds, as federal stimulus dollars were used in the GRF portion of the Department of Education budget in fiscal year 2010-11.

Table 3 breaks down the totals to show that formula aid increases for fiscal years 2014-15, the current biennium, were offset by larger decreases in tax reimbursements. The table compares basic state funding over three two-year budget cycles, showing the fiscal year and biennial totals.[28]

The changes in formula funding described above mask changes in distribution and accounting that affect districts’ bottom lines. Following are examples of how these changes can hurt districts even when they appear to increase overall funding.

Charter schools: These publicly funded, privately operated schools continue to open in Ohio, diverting money from district schools. At the beginning of the 2013-14 school year (fiscal year 2014), 52 new charters were set to open, including 17 in Columbus.[29] Ohio is one of the top three states in the nation in terms of the number of these schools, which serve about 7 percent of Ohio’s public school children.[30]

According to the Ohio Legislative Service Commission, charter school funding will increase by about $26.7 million in fiscal year 2014 even if enrollment does not go up. Although the state made a commitment that no district would lose formula funding for the 2013-14 school year (fiscal year 2014) compared to the 2012-13 school year, when the charter-school deduction is taken into account, 190 districts are set to get less than they did the year before. LSC calculations show that the Cleveland district takes by far the biggest hit, with about $4.5 million more being deducted this year than last. Five other districts see six-figure increases in the charter deduction. The average deduction increase for the 190 affected school districts was $39,289; the median was $7,044.[31] With HB 59, policymakers increased funding for private schools, both voucher and charter, in this year’s budget, despite much evidence that, overall, such schools do a worse job educating students.[32]

Transportation: Funding for transportation – school buses – was included in district formula funding this year; previously, it had been funded and accounted for in separate line items. Since transportation dollars are earmarked and cannot be used for general operating costs, this is an accounting change, not an increase in funding.

Straight A Fund: HB 59’s Straight A Fund is set to distribute $250 million in competitive grants during fiscal years 2014 and 2015. This new line item provides one-time grants to school buildings and districts, joint vocational school districts, Educational Service Centers, community schools, STEM schools, higher education institutions, and private entities; the aim of the grants is to achieve significant advancement in achievement, spending reductions, or use of more resources in the classroom. This is not a replacement for funding previously cut, since not all districts will get this funding and those that do have to propose new, targeted uses for the one-time money.

Tax changes: When state legislators eliminated property taxes on machinery and equipment (tangible personal property), the state promised to replace all lost local taxes for five years and to continue to provide schools with 70 percent of the new business tax that replaced it, even as direct replacement phased out. In the last two budgets, tax replacements were cut deeply. According to the Ohio Department of Taxation, the reduction in tax replacements for schools amounted to $966.8 million for fiscal years 2012-13 compared to 2010-11.[33] The reimbursements will continue to fall in the new budget: school districts will see nearly $250 million less in revenue sharing through tax replacements in fiscal years 2014-15 than in the previous budget.

Funds provided to districts through property tax rollbacks will be reduced in fiscal years 2014, 2015 and beyond. The reductions of 10 percent and 2.5 percent of tax bills for owners and owner-occupants, respectively, have been eliminated on new and replacement levies for schools and local governments. In addition, the Homestead Exemption was eliminated for new seniors making more than $30,000 a year (see p. 7). These changes are expected to make it more difficult for school districts to ask local taxpayers for help to restore school services.

Guarantee: Because of cuts the legislature and governor made to the budget for fiscal years 2012 and 2013, schools cut program and staff deeply. This budget’s formula funding continues to include a long-standing ‘guarantee’ to hold districts harmless from formula cuts, even if enrollment decreases. It is important to note that “Achievement Everywhere,” the Kasich administration’s education funding plan released in February 2013, stated that the guarantee creates “inequities [that] are unsustainable and unfair, and school districts should begin preparing for their eventual phase out.”[34] Even if it were to continue beyond the current budget cycle, the guarantee has been undermined by increasing allocations to charter schools and voucher programs, and because it does not cover loss of tax replacements.

Seventy percent of districts responding to a Policy Matters survey last fall reported that they had made cuts to their budget for the 2012-13 school year. Eighty-two percent cut staff, 43 percent increased class size and 23 percent reduced course offerings.[35] Funding in House Bill 59 is higher than in the last biennial budget, but is lower than the previous budget, is not stable and won’t allow schools to make permanent restorations.

Higher education funding

State-only GRF funding for higher education through the Ohio Board of Regents will increase by 5.3 percent or $238 million in the new budget compared to the prior budget. It is 5 percent less than in 2010-11, however, because of federal stimulus dollars used in the GRF component of the Board of Regents budget in fiscal years 2010-11.

GRF funding for the State Share of Instruction, which supports classroom teaching, will rise by $122 million, or 3.5 percent in fiscal years 2014-15 compared to 2012-13. The formula for distribution of the State Share of Instruction was changed in House Bill 59 to be heavily weighted toward college completion instead of enrollment. This approach makes sense in terms of helping ensure that enrollees are more likely to finish, but will have to be monitored to make sure that it doesn’t lead to creaming (failing to admit students from low-income families or with other perceived barriers to graduation).

GRF funding for the State Share of Instruction, which supports classroom teaching, will rise by $122 million, or 3.5 percent in fiscal years 2014-15 compared to 2012-13. The formula for distribution of the State Share of Instruction was changed in House Bill 59 to be heavily weighted toward college completion instead of enrollment. This approach makes sense in terms of helping ensure that enrollees are more likely to finish, but will have to be monitored to make sure that it doesn’t lead to creaming (failing to admit students from low-income families or with other perceived barriers to graduation).

Tuition in Ohio has soared over the past 15 years. The Board of Regents reports that during the past decade (2003 to 2012) tuition rose by 42 percent for community colleges (13 percent when adjusted for inflation) and by 56 percent at the four-year main campuses (25 percent when adjusted for inflation).[36] Ohio is known for having high tuition at public institutions relative to national averages, ranking among the top five for cost of public campuses as a share of family income. [37]

Need-based aid, which had dropped precipitously since fiscal year 2009, will increase in the new budget by $28 million, still far below the 2009 level (Figure 1). This Ohio College Opportunity Grant aid also leaves out community college students who used to be able to get help through the program.

State tuition caps have helped curtail tuition growth.[38] House Bill 59 caps annual in-state undergraduate tuition increases at the greater of 2 percent or $188 for university main campuses, the greater of 2 percent or $114 for university regional campuses, and $100 for community and technical colleges. It also allows a state university to establish an “Undergraduate Tuition Guarantee Program” under which the university guarantees a cohort a set rate of tuition for four years; the university is authorized to increase tuition by 6 percent for the first cohort and by the five-year inflation rate plus the tuition cap for subsequent cohorts.

Early learning and child care funds

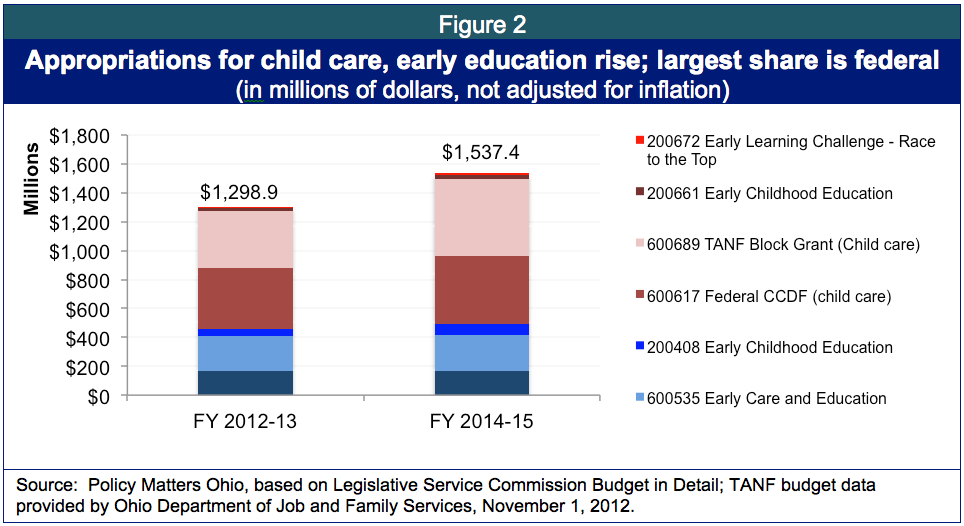

Appropriations for childcare and early learning will expand across seven agency line items in fiscal years 2014-15 compared with the budget for FY 2012-13 (Figure 2). Of that, a significant share results from a reallocation of funds from within the TANF block grant, permitted because the number of adults on cash assistance plummeted.[39] New GRF funding of $32.7 million in the Ohio Department of Education’s ‘Early Childhood Education’ line item (Agency Line Item 200408) will help between 6,000 and 7,000 children access pre-school.

Figure 2 illustrates the split between federal and state dollars for early education and childcare. State dollars are in shades of blue, the much larger federal dollars are in shades of red. A majority of the funding goes to child care subsidies.

Childcare subsidies have lagged need in Ohio. Unlike in other states, where eligibility is indexed to inflation, eligibility declined in Ohio as need rose. Eligibility for subsidized childcare in Ohio fell from $27,408 for a family of three in 2011 to $23,172 in 2012 – in other words, from 44 percent of the state median income level to 38 percent. This follows years of cuts in eligibility: In 2007, income eligibility was $31,764. [40] Although funding was expanded in the budget, using TANF dollars reallocated from Ohio Works First, eligibility was not expanded to allow more to participate.

Early learning has also lagged in Ohio. According to the National Institute for Early Education Research, Ohio fell from a 2002 ranking of 19th in the nation for enrolling 4-year-olds in state pre-K to 37th in 2012. On per-child spending, we fell from 6th in 2002 to 18th in 2012. [41] During budget deliberations, State Sen. Peggy Lehner asked for $100 million to put 22,000 of Ohio’s eligible children in preschool. Her request was funded at $32.7 million over the biennium, serving about a third of the number she had targeted. It is an important step in the right direction, but there is a long way to go to rebuild the infrastructure for Ohio’s next generation of learners.

Thriving communities

Municipalities, counties and townships provide the public services we depend on to work, learn and live in our communities. They are responsible for public health, public safety and other aspects of well-being. According to the Office of Budget and Management, aggregate state funding across 40 agency line items, for goods and services delivered at the local level, will have fallen by nearly a billion dollars (10 percent) between fiscal years 2010-11 and 2014-15.[42]

In this section, we look at revenue sharing for local government as well as funding for three services necessary to thriving communities: economic development, public transit and corrections.

Local government aid

Local government in Ohio is responsible for many services considered a state responsibility in other places. In recognition of a strong “home rule” tradition and differing regional needs, the state has provided flexible aid through mechanisms such as property tax relief and the Local Government Fund.

When the sales tax was established in the 1930s, proceeds were used to create the Local Government Fund to help counties and municipalities. When the income tax was established in the 1970s, substantial property tax relief (the 10 percent property tax rollback) was part of the deal. When local business taxes were eliminated during the past decade, the state pledged tax reimbursements.

The symbiotic relationship has been diminished. In the last budget, the Local Government Fund was cut in half. The phase-out of tax reimbursements was accelerated for local governments and the reimbursements themselves were greatly reduced for schools. On top of this, the state eliminated the estate tax, which affected only the wealthiest seven percent of Ohio estates. The tax was eliminated in the last budget, effective at the start of 2013. The estate tax was divided between state and local governments, with 80 percent of the proceeds going to local communities. It provided more than $600 million to communities throughout the state during fiscal years 2012-13.

The budget for fiscal years 2014-15 continues dismantling the fiscal pact between state and local government. It provides $95 million less in revenue sharing over the biennium when compared to fiscal years 2012-2011. The property tax rollback, through which the state buffers Ohio’s dependence on local property taxes for public services, has been eliminated for new and replacement levies.

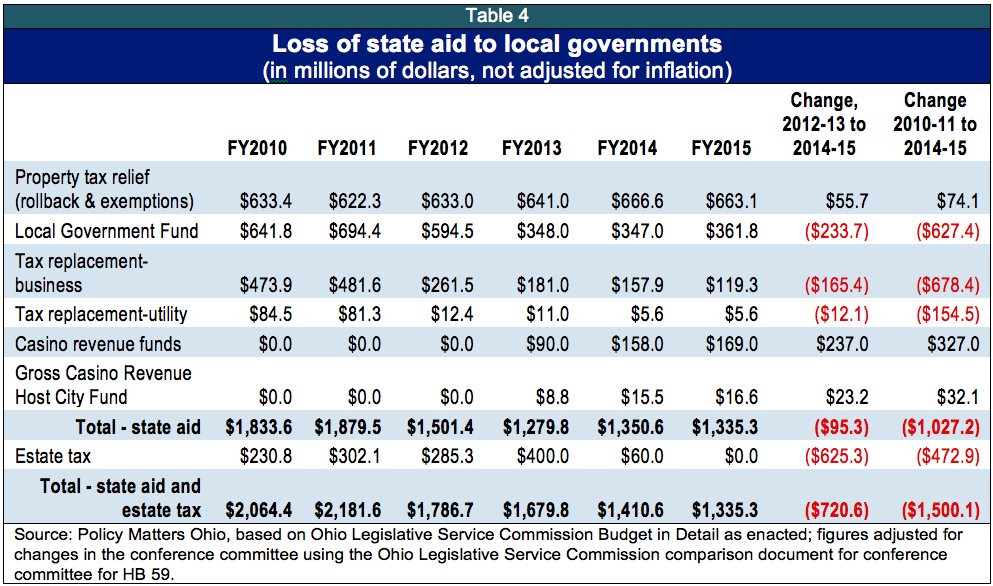

Altogether, local governments face the next two fiscal years with $720 million less in general-purpose revenues for local services than they had in fiscal years 2012-2013. They have $1.5 billion less than in fiscal years 2010-11 (Table 4).[43]

Ohio’s configuration of funding is unique among the states. For example, in 2010 the state provided a smaller share of funding for services for the developmentally disabled than any other state, and local government provided a larger share than in any other state.[44] State government in Ohio also provided a smaller share of children’s welfare financing than any other state. The average state provides 43 percent and the average locality nationwide provides just 11 percent – in Ohio those proportions are flipped with the state providing just 10 percent and localities providing 44 percent.[45] This is why cuts in flexible funds, which impact local levies supporting emergency services, parks, health and human services, and local government have had a harsh fiscal impact.

Economic development

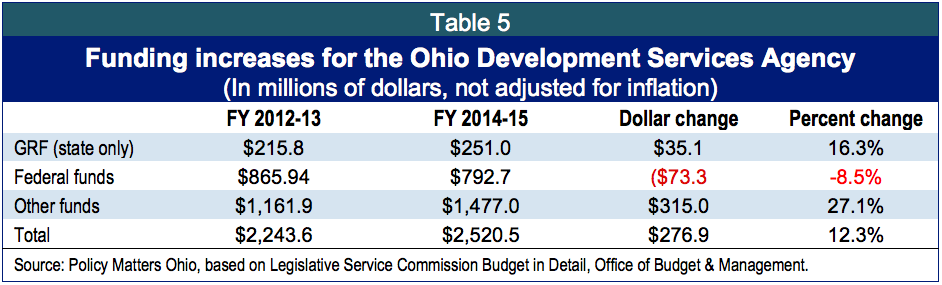

While certain economic development services have been privatized, funding for the state agency, now known as the Development Services Agency, has not decreased. Appropriations of state GRF within the Development Services Agency will increase by $35 million in FY 2014-15 compared to FY 2012-13, an increase of 16.3 percent. Although some programs related to industrial attraction and retention will end (Rapid Response grants, Ohio Industrial Training Program), others will increase (research and development and technology programs). There is also a jump in debt service related to the repayment schedule of refinancing.[46]

There are reductions in some federal line items, but overall funding increases in terms of the all-funds budget within the Development Services Agency (Table 5). This agency houses programs with significant funding from special state revenues: from incumbent worker training vouchers, funded by casino revenues, to low-income energy assistance, the Local Government Innovation Fund, and numerous research and development line items. The Housing Trust Fund, a line item within the Development Services Agency funded by fees, received appropriations of $106 million over the coming biennium.

The Development Services Agency also oversees a variety of business tax credits. While these are not considered in the budget process unless the General Assembly chooses to change them – there is no regular mechanism for reviewing tax expenditures – they have the same fiscal impact as state spending. These include, among others, three income-tax credits – the historic preservation credit, the motion picture credit and the small business investment credit – and four commercial activity tax credits, for job creation, job retention, research and development and net operating losses. Altogether, the taxation department estimated in its biennial tax expenditure report that the value of these credits would increase from $224.6 million in fiscal years 2012-13 to $368.4 million in 2014-15.[47]

Public transit

Within the GRF, state dollars dedicated to public transit (bus, rail and aviation) remain flat at $10.1 million for fiscal year 2014 and $10.1 million for 2015: this is the same as in fiscal years 2012 and 2013. GRF investment has fallen by 77.9 percent from $45.6 million in 2002. The 2012 Survey of State Funding for Public Transportation found that in 2010, Ohio tied with South Dakota for the eighth lowest investment of state-source funds among the 46 states (plus the District of Columbia) that put state dollars into public transit. (Total funding in 2010 was listed as about the same as in the current and past budget).[48] Ohio is a densely populated state, with the 7th largest population in the country. Funding for public transit should not mirror that of sparsely populated rural areas: it should be in the range of other densely populated states that fund public transit to get millions to work every day.

Public transit is funded out of both the state operating budget (HB 59) and the state transportation budget (HB 51). The combined total of state and federal funding will fall in this biennium compared to the prior one because of federal funding reductions. The federal stimulus boosted investment in public transit, and as stimulus dollars ebbed the state invested a share of federal dollars designated for “highway construction” in public transit. Even so, overall funding has fallen since 2011 (Figure 3). Fiscal problems at the local level, compounded by state cuts, have meant reduced services and increased fees. For example, according to the Ohio Public Transit Association, Cleveland has eliminated 24.6 percent of its services over the past decade and increased fares by 80 percent from $1.25 to $2.25; Dayton has eliminated 25 percent of services and doubled fares. [49]

Ohio legislators could help people get to work and stay employed by boosting investment in public transit. During discussions of Medicaid expansion, legislators focused on helping recipients move off public benefits, but lack of a ride to work is an important barrier to self-sufficiency. A recent study by the Brookings Institution found that in metropolitan areas, many lack access to public transit. Within all metropolitan areas in Ohio, at least a third of workers cannot commute on public transit within a reasonable amount of time. The Youngstown metropolitan area is 6th worst in the nation: only 12.1 percent of residents can reach jobs via public transit within 90 minutes. This is a particular problem for low-skilled workers and their employers: transit access is the worst in the suburbs, where low- and medium-skilled jobs are concentrated.[50]

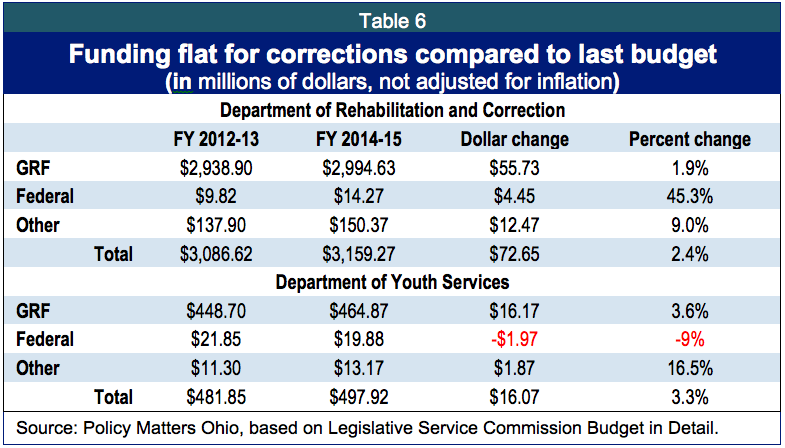

Corrections

GRF funding for the Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections will grow less than the inflation forecast in the executive budget, and GRF funding for the Department of Youth Services grows by only slightly more than inflation in FY 2014-15 compared to FY 2012-13 (Table 6).

ODRC will continue privatizing food services, laboratory services and recovery services. Medical and mental health services, combined in the budget for fiscal years 2014-15, will get a combined total funding that is $8.6 million less (1.7 percent) than in the prior budget period. Funding for community services was increased by about 5 percent in fiscal years 2014-15 relative to 2012-13.

The agency’s needs are growing even though funding is not. Sentencing reforms intended to reduce state inmate population have not; the current population of 50,419 (about 130 percent of capacity) may rise to over 52,000 in two years. The Correctional Institution Inspection Committee reports that inmates entering prison today have committed more serious crimes with longer sentences. In addition, the growing number of women entering the system was not anticipated. [51]

Funding for the Department of Youth Services increases very slightly in fiscal years 2014-15, allowing it to keep up with inflation. DYS is in the final year of settling a class action lawsuit over conditions for inmates and has taken actions to reform the state's juvenile justice system in order to be in compliance with the settlement agreement.[52]

Healthy people and environment

Public services help keep people healthy, take care of the aged and help families of the developmentally disabled. These services make sure we have clean water to drink, provide nutritional aid for mothers and children, and help prevent outbreaks of disease. Many people suffer from mental health or addictions: services help with recovery. The public sector keeps people healthy and safe in other ways, too, making sure dams and waterways are safe, ensuring soil and watersheds are in good shape, and monitoring livestock, poultry and food supply in stores.

In this section we review some of the major developments in health, human services, natural resources, environmental protection and agriculture.

Funding for health care services will grow in fiscal years 2014-15 in Medicaid, both in the new Department of Medicaid and in the agencies supported by Medicaid funding: Aging, Mental Health and Addiction Services, Developmental Disabilities, Department of Health and Department of Job and Family Services. In non-Medicaid appropriations, human service agencies will see mostly flat funding. GRF funding for the Ohio Department of Natural Resources rises by 29.5 percent, for Agriculture by 8.9 percent.

Health care

Medicaid is Ohio’s largest health payer: Ohio’s Medicaid program supported 83,000 doctors, hospitals, nursing homes and other providers that cared for 2.2 million Medicaid patients in 2012. According to the Legislative Service Commission, the Medicaid budget includes state and federal GRF appropriations of $14.70 billion in fiscal year 2014 and $15.61 billion in 2015. The state share is $5.74 billion in fiscal year 2014 and $6.11 billion in 2015.[53] Medicaid dollars support other state agencies as well, including the Ohio Departments of Aging, Developmental Disabilities, Job and Family Services, Health and Mental Health and Addiction Services.

Ohio spends more per person on health care than typical for the nation.[54] Health reform under the Affordable Care Act has the potential to curtail growth in health care costs by allowing early diagnosis and appropriate treatment through universal access to a doctor’s office and preventative care. Care for those too poor to buy health insurance would be provided to all through an expansion of Medicaid.

The Kasich Administration proposed to expand Medicaid in the executive budget proposal, estimating that it would cover 275,000 newly eligible Ohioans in fiscal years 2014-15. This group is made up primarily of very low-income workers who do not have children, as well as parents making between 90 and 100 percent of the federal poverty line. Federal funds would pay the entire cost for this expansion from 2014 to 2017. After that the federal share steps down to 90 percent by 2022 and thereafter. This is much higher federal reimbursement than in the rest of Medicaid, where the federal government pays about 64 cents of each dollar. The General Assembly did not put Medicaid expansion in the budget, although it would have been paid for by federal dollars, freed up a half billion in state dollars for other uses,[55] and put $2 billion in federal funds into the Ohio economy.

According to the Ohio Legislative Service Commission, initiatives funded within the Medicaid budget in fiscal years 2014-15 include:[56]

- $398.1 million in fiscal year 2014 and $261.9 million in 2015 of GRF Medicaid appropriations to pay certain primary care physicians at the higher Medicare rate. The federal government will reimburse 100 percent of the increased costs. This was due to a federal requirement.

- $357.5 million ($131.7 million state share) in fiscal year 2014 and $449.3 million ($166.2 million state share) in 2015 for an Integrated Care Delivery System to provide coordinated care for 114,000 individuals who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. Enrollment is to begin in fiscal year 2014.

- $83.3 million ($30.7 million state share) in fiscal year 2014 and $176.7 million ($65.3 million state share) in 2015 to continue a 5 percent rate add-on for hospital inpatient and outpatient services.

- $7.2 million per year in GRF funding and the corresponding federal reimbursements for county departments of job and family services for the costs related to transitioning to a new public assistance eligibility determination system as required by federal health reform.

In addition, the Administration applied for and received $169 million for home and community-based health care services through a federal program authorized under the Affordable Care Act, the “Balancing Incentives Payment Program,” that boosts federal match for improving the system for home and community based care. This will allow seniors to stay in their homes instead of nursing homes or other types of institutions. This contributes to the health care initiatives undertaken in FY 2014-15.

Human Services

Government provides services for individuals and families. In addition to health, these safeguards include protecting vulnerable children and seniors, providing meals for disabled and elderly Ohioans, training and transition assistance for those who lose their jobs, funding for food pantries, and nutritional assistance for women, infants and children.

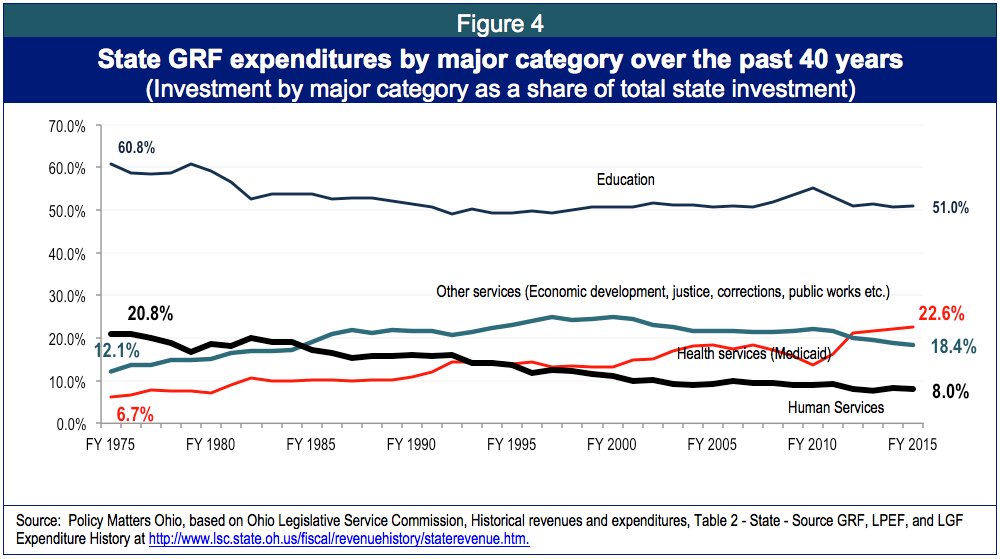

This vital part of public service is mostly funded by the federal government. The share of state-only GRF funding for human services as a share of the budget has declined over the past 40 years. In 2015, it will comprise 8 percent of state-only GRF spending, down by almost two thirds (Figure 4).

In the new budget, appropriation of state-only GRF funding other than Medicaid for the Ohio departments of health, job and family services, aging, mental health and addiction services, developmental disabilities and other disabilities, is essentially flat compared to fiscal years 2012-13.

Federal dollars constitute the majority of funds in many health and human service agencies.[57] As this report goes to press, the federal government is being shut down. In Ohio that shutdown, if it drags on, will have the harshest impact on health and human services because of dependence on federal dollars. While the federal shutdown is the most immediate threat to human services, there is also ongoing reduction of federal dollars. Congress has set in place an automatic mechanism to cut the federal budget in many program areas, known as sequestration. Medicaid and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families are not included in sequestration, but other important programs are, including Women, Infants and Children (WIC), the nutritional aid program that supports the families of half of the infants born in Ohio.[58] Sequestration will cut certain federal programs, year over year, unless Congress puts a halt to it. Many agencies do not yet know what the impact of the federal sequester will be in the coming biennium. Budget documents do not highlight planning for these cuts.

Mental health and addiction services: GRF funding for the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services will be $1 billion in the budget for fiscal years 2014-15, a decline of 1.9 percent over the prior budget.

When the General Assembly withdrew Medicaid expansion from the budget, it also boosted state investment in community mental health services. This was badly needed: According to the Ohio Association for County Behavioral Health Authorities, by January of 2012, non-Medicaid funding for community mental health services had been cut by 70 percent since 2002 and non-Medicaid community addiction services had been cut by 35 percent since 2005.[59] The budget increases GRF funding for community behavioral health boards by $47.5 million per year, earmarks $17.5 million per year for addiction services and $30.0 million per year for mental health services and provides $5.0 million in fiscal year 2014 for an addiction treatment pilot program.[60] Lorain County Board of Mental Health Director Charles A. Neff, however, in testimony to the House Tax Reform Legislative Study Committee, pointed out that county boards of mental health across the state are receiving less funding today than in 2002, even after new funding in the budget for fiscal years 2014-15.[61]

The Ohio Office of Health Transformation indicates that more than $700 million additional dollars would have been available for mental health and addiction services if Medicaid expansion had been left in the budget.[62] The restoration of GRF funding to community mental health is welcome, but Ohio still lags, even before the eroding effect of inflation is taken into account. Medicaid expansion would help in many ways.

Ohio Department of Aging: State GRF funding within the Ohio Department of Aging will be $29.3 million dollars for fiscal years 2014-15. GRF spending rises by 2.7 percent (less than a million dollars) in fiscal years 2014-15 compared to 2012-13.

The state budget for fiscal years 2014-15 adds $6 million for PASSPORT, the largest of several Medicaid programs providing home and community-based services to help seniors and disabled adults stay in their homes instead of moving to nursing homes. There have been concerns that a lack of funding in some aspects of PASSPORT slowed the state’s goals of supporting more seniors in home and community-based care instead of institutional care.[63] The new investment of this budget may help, but monitoring will be needed.

Department of Developmental Disabilities: State GRF funding for the Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities will be $1.1 billion in fiscal years 2014-15. The new state budget increases the GRF funding by $237 million dollars (29 percent) in 2014-15 compared to 2012-13.

GRF dollars account for 20 percent of the agency’s budget. Most GRF dollars are used as the Medicaid state share for home and community-based waiver services, services provided in developmental centers, and payments to private intermediate care facilities that provide housing and care for people in need of help in the activities of daily living.

The state budget for fiscal year 2014-15 increases funding by $8 million for home care providers who help developmentally disabled people stay in their homes instead of having to live in institutions. Rates of pay to direct service workers – the front-line home health care workers who come into homes and help the disabled – are very low. The Ohio Providers Resource Association (OPRA), the trade association of providers of services for the developmentally disabled, found that 90 percent of its members have employees who earn so little that they are eligible to receive health care through Medicaid. Turnover among the direct care workforce is more than 43 percent annually.[64] Pay is so low that the workers providing this service - a public service, since it is largely funded through federal and state funds - struggle to get by:

First, I would like to provide you with a candid description of day-to-day life for our system’s low-wage workers. It is not a simple existence, reality is often harsh and in our system we often lose good, compassionate, hard-working employees because of low wages and lack of health insurance. Every day, our direct care staff are faced with tough decisions about how to spend their hard earned pay. Food or gas? Clothes or health care? - Mark Davis, President of Ohio Providers Resource Network, testimony to the Ohio Senate, May 29 2013.[65]

This creates poorly compensated jobs, fosters a lack of stability in care and highlights the worst results of Ohio’s lean state budget.

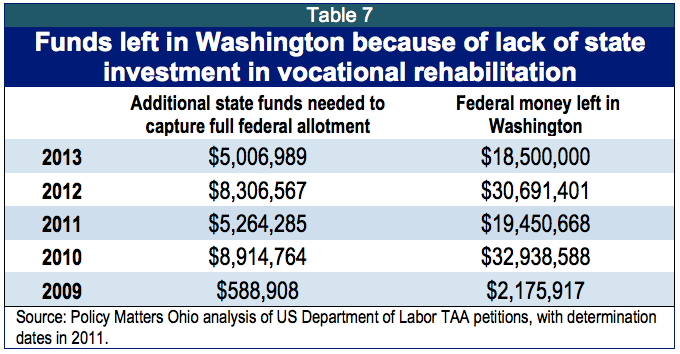

Opportunities for Ohioans with Disabilities: This agency, formerly known as the Ohio Rehabilitation Services Commission, will get additional GRF funding of $5 million in fiscal years 2014-15, bringing total GRF funding over the biennium to $31.4 million, an increase of 19.2 percent.

Added investment builds a base that allows the state to draw down federal match for each state dollar invested. Previous cuts in state funding resulted in a sharp drop in number of Ohioans with disabilities aided through this department since the recession: from 9,370 in 2008 to 3,510 in 2012, a decline of 62.5 percent.[66]

Added investment builds a base that allows the state to draw down federal match for each state dollar invested. Previous cuts in state funding resulted in a sharp drop in number of Ohioans with disabilities aided through this department since the recession: from 9,370 in 2008 to 3,510 in 2012, a decline of 62.5 percent.[66]

The Rehabilitation Services Administration of the federal Department of Education shows that in 2013, Ohio left $18.5 million of the federal allotment for vocational rehabilitation services on the table in Washington D.C. A $5 million state investment could have brought that money into Ohio, providing services and boosting the economy. Ohio has left funds in Washington for the past five years (Table 7).

The Legislative Service Commission’s ‘Red Book’ for OOD indicates that $130 million federal dollars annually is available for Ohio in vocational rehabilitation services grant funding during 2014 and 2015,[67] but the appropriations for fiscal years 2014 and 2015 respectively are $117 million and $113 million. Ohio will miss the mark again in the current biennium.

Ohio Department of Health: GRF funding for ODH will grow by $14.4 million dollars (8.8 percent) in fiscal years 2014-15 compared to fiscal years 2012-13. Total GRF funding is $177.2 million. A new initiative addressing infant mortality was created and will be funded over the biennium at $6.2 million. Tobacco cessation programming is funded at $2.1 million. Help Me Grow, a program that helps new parents, has been slashed over the past decade, but sees $3.1 million in restored funding.

Ohio Department of Job and Family Services: State-only GRF funding for ODJFS, net of most of the health care services largely transferred to the new Department of Medicaid, will grow slightly compared to fiscal years 2012-13. State-only GRF funding for this agency will be $1.4 billion in fiscal years 2014-15.

One of the most troubling elements of state funding concerns Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. TANF is the main welfare program, serving people making 50 percent of the federal poverty level or less, and is housed in ODJFS. Since January of 2011, the number of adults receiving cash assistance under Ohio Works First (OWF) has dropped by almost two-thirds, but the number of children has dropped by far less: just over a third.[68] About two-thirds of Ohio Works First cases statewide are now child-only, meaning that the eligible child receiving benefits does not reside with his or her parents.[69] There is concern that the program is not keeping needy families together, but splitting them apart.

Across the state, at least half of all OWF recipients are required to work or participate in work activities at least 30 hours per week. Ohio did not meet these standards during and after the recession, and faced federal financial penalties. According to the Center for Community Solutions, the state came into compliance with federal requirements because caseloads fell, not because the number of adults completing work assignments increased. The number of working families has not exceeded 13,700 since January 2011, and it reached a two-year low of 9,490, in June 2013.[70] A recent study commissioned by the state found local efforts to comply with federal work participation requirements focused on diversion or even reducing programs that would help people succeed at the required participation rates or find jobs.[71]

The state has changed internal program funding for TANF, using program funds made available by the decline in adult caseload to boost work supports. Supports should have been in place all along, especially when the need was the highest. Better funding is needed to ensure critical work support programs are adequately funded with greater state GRF investment.

Healthy environment

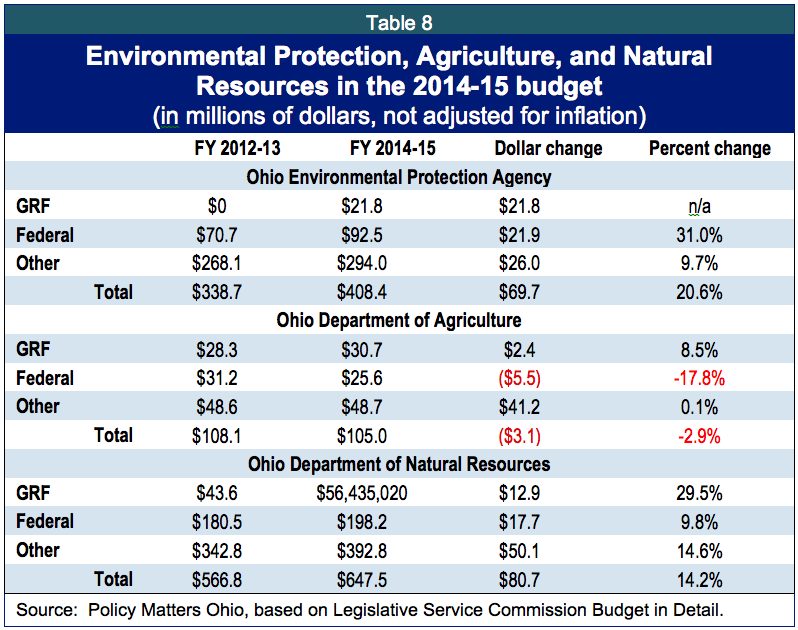

The health of people and communities depends on good stewardship of the environment. Three state agencies bear primary responsibility for this stewardship: The Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, the Ohio Department of Agriculture and the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. Funding will rise in the budgets for the EPA and DNR, and decrease modestly, as a whole, for Agriculture (Table 8).

An adjustment of a funding line within the Ohio EPA puts GRF funding directly into the budget of the agency: most state funds for this agency come from user fees. The state agriculture department budget for fiscal years 2014-15 drops modestly when compared with the prior biennium. ODNR sees an increase of $12.8 million in fiscal years 2014-15 compared with the prior biennium. A jump in lease and debt service payments – which account for 48 percent of the GRF in this agency - accounts for an important share of the growth.[72] In addition, an improved oil and gas regulatory infrastructure, water quality programming and fee-based services drive increased appropriations within ODNR.

Summary and conclusion

In an August speech entitled, “Economic Outlook: What Matters Nationally and Locally,” Sandra Pianalto, chair of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, cited a 2006 study by Cleveland Fed researchers and noted that, “It found that regions with higher levels of education and innovation see higher rates of income growth. That is no less true today than it was when I first said it years ago.”[73] She went on to urge her Cleveland audience to “continue investing in human capital. In doing so, we can ensure that our area’s workforce is educated and innovative, and we can attract new companies and good jobs to our area. By focusing on building a skilled workforce over the long run, we can make Northeast Ohio a region that is ready and able to meet the opportunities of the twenty-first century.”

A state budget should invest in human capital, support thriving communities and enhance the health of people and the environment. The budget for fiscal years 2014-15 is better than the last, but does not invest enough to meet needs, and misses critical opportunities.

Program improvements in health care are expected to yield better services and long-term savings. But legislators missed the biggest opportunity: Medicaid expansion, which would provide health care for 275,000 low-income Ohioans, reduce costs, bring in federal dollars and help our economy.

The budget invests in schools, but doesn’t fully restore the $1.6 billion cut in the last budget period. Many public school districts, which educate 92 percent of the children of Ohio, see state formula funding eroded by an increase in money for charter schools, too many of which have a bad track record.

The prior budget was particularly hard on services that support thriving communities. Revenue sharing funds, cut in half in the last budget, are not restored in the budget for fiscal years 2014-15, and even less flexible revenue sharing funds will flow to local communities than during FY 2012-13.

Increases in human service spending, though critically important to specific programs and areas, scarcely offset reductions in the last budget through elimination of tax replacements, part of the local government cuts. An estimated $210 million was cut in state tax replacements to local property tax levies supporting senior services, children’s services, mental health and developmental disability services and health departments in fiscal years 2012-13. These cuts are not restored in the budget for 2014-15.[74] Unmet needs in these areas reduce community stability, but there are particular concerns now about inadequate mental health services in the wake of recent mass shootings. The Medicaid expansion could have contributed $700 million to needed mental health and addiction services in Ohio.

By and large, investment of the kind specified by Pianalto as promoting long term economic growth has not been embraced in this budget, nor in the previous one. Ohio’s track record on job creation since 2005, when the tax cut strategy was first implemented, shows that decisions to prioritize tax cuts over investment have not boosted our state’s economy. Continued pursuit of this strategy will not boost our economy in the future.

[1] State-only GRF rises by about 7 percent in FY 2014 and over 4 percent in FY 2015 for the 11.4 percent total. This is greater than the increase allowed under the State Appropriations Limit (SAL), but the increase accounted for here includes some items not considered in the base for the SAL (such as property tax relief). Moreover, the General Assembly altered the SAL. According to Gongwer Ohio: “The biennial budget included a revision to the SAL to ensure the limit is adjusted when a special fund that was ultimately reimbursed by the state gets moved to the GRF.” www.gongweroh.com/programming/news.cfm?article_ID=821300202 - sthash.6GA0buh2.dpuf.

[2] Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities at http://dodd.ohio.gov/medicaid/Pages/Waiting-List.aspx.

[3] U.S. Department of Labor, Employment & Training Administration, Trust Fund Loans, Sept. 26, 2013, retrieved from http://workforcesecurity.doleta.gov/unemploy/budget.asp#tfloans

[4] Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Budget Footnotes, July 2012 (p.5) at www.lsc.state.oh.us/fiscal/bfn/v35n11.pdf; Budget Footnotes, July 2013 (p.5) at www.lsc.state.oh.us/fiscal/bfn/v36n11.pdf.

[5] Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Budget Footnotes, “Personal income tax revenues,”

July 2012 (p.6) and, July 2013 (p.6).

[6] Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Budget Footnotes, July 2012; see also, Office of Budget and Management, “Comprehensive Accounting Review Report” (CAFR), 2012: “On February 1, 2013, the State transferred its spirituous liquor distribution and merchandising operations for a period of 25 years to JobsOhio Beverage System in exchange for a payment of $1.46 billion. A portion of this payment provided for the payment of all debt service on the outstanding Economic Development and Revitalization revenue bonds and notes. Pursuant to the transaction agreement, the State will forgo deposits to the GRF from the net liquor profits and may not issue additional obligations secured by a pledge of profits from the sale of spirituous liquor during the 25-year term.”

[7] Ohio Office of Budget and Management, Monthly Financial Report, July 2013 at http://media.obm.ohio.gov/OBM/Budget/Documents/mfr/2013-07_mfr.pdf.

[8] Testimony of Director Tim Keen to the Conference Committee on the FY 2014-15 Main Operating Budget, 6/18/2013.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Some of the available revenue results from the major cuts made in support to local governments. See Wendy Patton, Policy Matters Ohio, Three Blows to Local Government: Loss in state aid, estate tax, property tax rollback, July 24, 2013 available at www.policymattersohio.org/local-gov-jul2013

[11] See “Schiller testifies before House Ways & Means subcommittee on HB 59 sales-tax plan,” Policy Matters Ohio, March 7, 2013, available at www.policymattersohio.org/sales-tax-testimony-mar2013.

[12] Patton, Wendy, Statement: Severance tax proposal is responsible and simple, Prepared Comments on House Bill 212, June 19, 2013, available at www.policymattersohio.org/severance-jun2013.

[13] Schiller, Zach, Policy Matters Ohio, Tax breaks grow in new Ohio budget, Aug. 8, 2013, available at www.policymattersohio.org/tax-breaks-aug2013.

[14] See Michael Mazerov, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Testimony to House Finance and Appropriations Committee On HB 59 Income Tax Plan, March 19, 2013, available at www.policymattersohio.org/mazerov-mar2013, and Zach Schiller, Policy Matters Ohio, Tax Break for Business Owners Won’t Help Ohio Economy, April 2, 2013, available at www.policymattersohio.org/tax-break-apr2013.

[15] That number does not include what are likely to be sizeable additional revenue losses in fiscal year 2014, because beneficiaries of the exemption are likely to have more tax withheld this year than is eventually needed to pay their full year tax bills.

[16] Emails from Gary Gudmundson, Ohio Department of Taxation, July 17 and July 24, 2013. The department did not include the new business-income exemption in this analysis.

[17] Jon Honeck of the Center for Community Solutions pointed out in a report last year that a considerable number of higher-income individuals also are claiming the $10,000 credit by using other credits and deductions. As Honeck advised, this loophole should be closed and income limits set on the use of the low-income credit. See Honeck, Jon, “Closing the Loophole in Ohio’s Low-Income Tax Credit,” Center for Community Solutions, Oct. 26,2012, available at www.communitysolutions.com/associations/13078/files/sbmV8N6LowIncomeCredit JHoneck102612.pdf. However, overall, Ohio starts taxing its residents at a lower income than most states with income taxes. A report last year by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that in 2011, Ohio was one of only five states that taxed two-parent families of four with income less than three-quarters of the federal poverty line or $17,264. While a large share of Ohioans with incomes below that level are effectively exempt from the state income tax because of the low-income and other credits, it shows that some Ohioans in extreme poverty continue to pay the tax. Phil Oliff, Chris Mai, and Nicholas Johnson, The Impact of State Income Taxes on Low-Income Families 2011, available at www.cbpp.org/files/4-4-12sfp.pdf

[18] The bottom fifth of Ohioans, who made less than $17,000 in 2010, on average pay 11.6 percent of their income in state and local taxes, compared to the top 1 percent, who earned more than $324,000 that year, and on average pay just 8.1 percent. See Policy Matters Ohio, Ohio’s state and local taxes hit poor and middle class much harder than wealthy, Jan. 30, 2013, available at www.policymattersohio.org/income-tax-jan2013.

[19] The ITEP analysis covers Ohio residents and is based on 2012 income levels. It includes the following components of the tax changes: The 10 percent income tax rate cut; the business-income tax exemption; the increase in the state sales tax from 5.5 percent to 5.75 percent; the tiered minimum taxes under the Commercial Activity Tax; the elimination of the $20 personal exemption credit for those with $30,000 or more in annual income; the repeal of the income-tax deduction for gambling losses, and the new Earned Income Tax Credit. The analysis does not include five other changes in sales or income taxes, and two property-tax changes that will affect taxpayers in future. These are either quite small or not easily modeled. The numbers in this analysis for those with income between $51,000 and $78,000 are slightly different than the figures Policy Matters published in June because of an updating by ITEP. That report is available at www.policymattersohio.org/itep2-jun2013.

[20] Policy Matters Ohio, “Ohio’s state and local taxes hit poor and middle class much harder than wealthy,” Jan. 30, 2013, available at www.policymattersohio.org/income-tax-jan2013.

[21] Rothstein, David, Policy Matters Ohio, “Small Investment, Big Difference: How an Ohio Earned Income Tax Credit Would Help Working Families,” March 15, 2013, available at www.policymattersohio.org/eitc-mar2013.

[22] Kent, Matthew, “Local officials want funding returned,” The Chillicothe Gazette, Aug. 14, 2013, available at www.chillicothegazette.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=2013308140028&nclick_check=1.

[23] Ohio Department of Taxation, Tax Data Series, Real Estate Taxes: Real Property Tax Relief: Ten Percent and Two and One Half Percent Rollbacks, and Homestead Exemption, by County, Distributed during Calendar Year 2012 (for Tax Year 2011), available at www.tax.ohio.gov/tax_analysis/tax_data_series/publications_tds_property/PD1CY12.aspx.

[24] The $30,000 limit excludes Social Security retirement income, so it amounts to a higher threshold for most retired homeowners.

[25] For example, the exemption could be phased out, decreasing as income increases. Or a sliding scale could be devised, under which property owners would qualify if property taxes amounted to more than a certain percentage of income (the percentage would be lower for the poorest homeowners, and rise so that more affluent homeowners would need to be paying a larger share of their income in property taxes to qualify).

[26] Email from Gary Gudmundson, Ohio Department of Taxation, Sept. 6, 2013. The FY2015 estimate includes tax receipts for only three quarters of the year because of when the tax is paid.

[27] Timothy S. Keen, director, Office of Budget and Management, Amended Substitute House Bill 59, Conference Committee Testimony on the FY 2014-2015 Main Operating Budget, p. 5. The budget is based on a forecast by IHS Global Insight that shows Ohio lagging in job gains.

[28] On August 21, 2013, the Ohio Office of Budget and Management provided a document to the House Tax Reform Legislative Study Committee that defined state aid to local schools far more broadly than the Legislative Service Commission (Table 1). The OBM document, entitled “Fact Sheet: Funding Ohio Communities,” included Agency Line Item (ALI) 200426 (Ohio Educational Computer Network), 200502 (Pupil Transportation), 200540 (special education enhancements), 200550 (foundation funding) and 200612 (lottery profits – foundation funding). Revenue sharing – tax reimbursements (ALI 200909 and 200900) and property tax relief (ALI 200901), as well as debt service for school facilities (ALI 230908)– were accounted for elsewhere on the fact sheet. According to the OBM calculations, the loss to schools between FY 2010-11 and FY 2014-15 is only $53 million, when all funds, including federal stimulus funds, are included.

[29] Bush, Bill, The Columbus Dispatch. “Charter schools’ failed promise,” September 1, 2013. Retrieved at www.dispatch.com/content/stories/local/2013/09/01/charter-schools-failed-promise.html.

[30] Bridge Worksheet report from Ohio Department of Education, July 2013. This document shows total Average Daily Membership for Ohio public schools is 1,766,091, with charter enrollment at 116,139.

[31] “Charter School Deductions by District,” from the Ohio Legislative Service Commission. Also see O’Donnell, Patrick, “State aid could fall for nearly 200 school districts under new budget, once money for charter schools is deducted (database).” The Plain Dealer, September 5, 2013. The estimates for increased charter deductions from fiscal year 2013 to 2014 range from $25 for St. Henry Consolidated Local to $4.5 million for Cleveland.

[32] See more at: policymattersohio.org/privatization-jan2013. Also see the Sept. 1, 2013, Dispatch article by Bill Bush, “Charter schools’ failed promise,” dispatch.com/content/stories/local/2013/09/01/charter-schools-failed-promise.html and “National Charter School Study,” 2013, by The Center for Research on Education Outcomes, Stanford University.

[33] Ohio Department of Taxation, “Explanation of law changes enacted in 2011 relative to the reimbursement of foregone tangible personal property taxes and modifications in state tax revenue streams,” May 1, 2012, p.16 and 17.

[34] “Achievement Everywhere: Common Sense for Ohio’s Classrooms,” John R. Kasich, Governor of Ohio, retrieved at www.governor.ohio.gov/PrioritiesandInitiatives/K12Education/AchievementEverywherePlan.aspx.

[35] van Lier, Piet, and Wendy Patton, “Ohio shrinks its schools: State cuts lead to larger class sizes, fewer course offerings,” Policy Matters Ohio at

[36] Ohio Board of Regents, “Undergraduate Tuition and Fees, 2003-2012” at https://www.ohiohighered.org/files/uploads/reports/Undergrad_Tuition_Fees_FY2003-12.pdf

[37] National College and Higher Education Management Systems’s Information Center, College Affordability, 2010.

[38] According to the College Board’s “Trends in Student Pricing,” growth of tuition over the last 5 years has been among the lowest of the states at both 2-year and 4-year public campuses. (http://trends.collegeboard.org/college-pricing).

[39] A recent study found that counties often followed state directives to comply with federal work participation requirements for recipients by reducing programs that would help people succeed at the required participation rates or find jobs: see Public Consulting Group, “Ohio Works First Participation Improvement Project,” Review, Assessment, and Recommendations for Improvements to County Agency Work Activity Processes, May 2013.

[40] National Center for Children in Poverty, State Profile at http://bit.ly/VmH6Rg.

[41] Barnett, W.S., Carolan, M.E., Fitzgerald, J., & Squires, J.H. (2012). The state of preschool 2012: State preschool yearbook. New Brunswick, NJ: National Institute for Early Education Research.

[42] Policy Matters Ohio, “State Aid to Local Governments is Down,” Testimony of Wendy Patton to the House Tax Reform Legislative Study Committee, September 12, 2013 at http://www.policymattersohio.org/local-govt-sept2013, see also Ohio Office of Budget and Management, “Fact Sheet: Funding Ohio Communities,” presentation to the House Tax Reform Legislative Study Committee, August 21, 2013.

[43] The numbers in Table 4 include sources of flexible funding for unique local needs. The many sources used by the Ohio Office and Budget and Management’s document “Fact Sheet: Funding Ohio’s Communities” (see footnote # 43) include these numbers, but the majority of the funds in that analysis are dedicated for a specific program or use; they are not flexible revenue sharing funds.

[44] University of Colorado, State of the States in Developmental Disabilities, “State profiles for I/DD during fiscal years 1977-2011 at www.stateofthestates.org/index.php/intellectualdevelopmental-disabilities/state-profiles.

[45] Public Children’s Services Association of Ohio, “PCSAO and Child Welfare Financing,” June 2013 at www.pcsao.org/Presentations/2013/Child Welfare OH Financing Execs 6 13.pdf.

[46] E-mailed communication from the state, with Debt Managers Kurt Kauffman and Dave Pagnard of the Ohio Office of Budget and Management, dated 9/20/2013.

[47] Governor John R. Kasich, Ohio Department of Taxation, The State of Ohio Executive Budget, Fiscal Years 2014-2015, Tax Expenditure Report, retrieved from http://media.obm.ohio.gov/OBM/Budget/Documents/operating/fy-14-15/bluebook/budget/Tax_14-15.pdf A fourth business-related income-tax credit, the technology investment tax credit, was eliminated in the budget. It was worth nearly $4 million a year in FY12 and FY13.

[48] American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, Survey of State Funding for Public Transportation, Final Report, 2012 (Table 1-8. Changes in State Transit Funding Levels, 2009–2010) at http://scopt.transportation.org/Documents/SSFP-6.pdf.

[49] This is taken from a letter from the Ohio Public Transit Association to Jerry Wray, Director of the Ohio Department of Transportation, dated April 11, 2013. Note: Fare increases are not due to inflation: according to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics Inflation Calculator, prices increased 27.62 percent between 2002 and 2012.

[50] Adie Tomer et.al., “Missed Opportunity: Transit and Jobs in Metropolitan America,” May 2011 at http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2011/05/12-jobs-and-transit

[51] Correctional Institutional Inspection Committee, “DRC Population overcrowding 2013” at http://ciic.state.oh.us

[52] Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Red Book for the Department of Youth Services for FY 2014-15 budget at http://www.lsc.state.oh.us/fiscal/redbooks130/dys.pdf

[53] Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Budget in Brief at http://www.lsc.state.oh.us/fiscal/budgetinbrief130/budgetinbrief-hb59-en.pdf

[54] Ohio Medicaid Reform, Testimony of Greg Moody, Director of the Governor’s Office of Health Transformation to the House Finance and Appropriations Group, May 7, 2013 (p.8). at http://1.usa.gov/1a2d9vH.

[55] Ohio Office of Health Transformation, “State GRF Impact of House Sub Bill's Removal of Medicaid Expansion & Additional Related State Spending,” http://1.usa.gov/1eZCjkj.

[56] Ohio Legislative Service Commission Budget in Brief for HB 59 as enacted at http://bit.ly/1buRkqD.

[57] Wendy Patton, The Budget Control Act of 2011: Impact on Public Services in Ohio, Policy Matters Ohio, March 2013 at www.policymattersohio.org/budget-control-act-march2012.

[58] Ohio WIC Annual Report, 2010 at http://www.zmchd.org/pdfs/WAR.pdf.

[59] Cheri Walters, “Losing the local behavioral health safety net,” Ohio Association for County Behavioral Health Authorities, January 2012 at http://oacbha.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Jan-2012-OACBHA-News.pdf

[60] Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Budget in Brief (FY 2014-15) at http://bit.ly/15L9xvm.