Flawed Tax Cuts in Senate Budget Bill

May 27, 2014

Flawed Tax Cuts in Senate Budget Bill

May 27, 2014

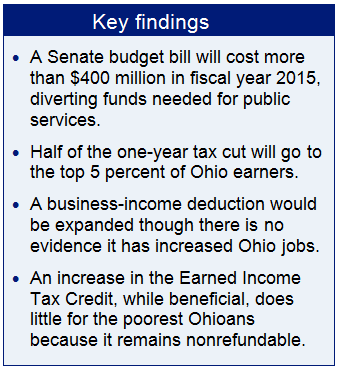

Download summary (2pp) Download report (8pp)Press releaseThe Senate tax changes will siphon more than $400 million next fiscal year into tax cuts: mostly to affluent Ohioans. While increasing the Earned Income Tax Credit is a step in the right direction, EITC must be made refundable to provide real benefits to poor Ohioans. Instead of more tax cutting, Ohio should invest in education and the infrastructure that will support enterprise and real job creation.

Fiscal year 2015 reductions divert funds, flow mostly to the affluent

A state budget bill approved by the Ohio Senate last week includes substantial new tax cuts, adding up to more than $400 million in Fiscal Year 2015.[1] While the biggest part of that reduction is limited to one year only, it diverts significant funds from needed public services.[2] At the same time, a new analysis shows that half of the one-year tax cut will go to the top 5 percent of Ohio earners. The top 1 percent will get a tax cut for the year averaging $1,846, while the poorest fifth of Ohioans will see just a $4 reduction.

A state budget bill approved by the Ohio Senate last week includes substantial new tax cuts, adding up to more than $400 million in Fiscal Year 2015.[1] While the biggest part of that reduction is limited to one year only, it diverts significant funds from needed public services.[2] At the same time, a new analysis shows that half of the one-year tax cut will go to the top 5 percent of Ohio earners. The top 1 percent will get a tax cut for the year averaging $1,846, while the poorest fifth of Ohioans will see just a $4 reduction.

The tax changes in the Senate version of House Bill 483 include two permanent provisions aimed at lower- and middle-income Ohioans, an expansion of the state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and increases in personal exemptions to the state income tax for those earning up to $80,000 a year. However, as an analysis by the nonprofit research group Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) reveals, these provisions reflect only very modest savings for middle-income Ohioans and almost nothing for the poorest Ohioans. For it to provide meaningful benefits to those at the bottom of the income scale, who need it most, the state EITC needs to be refundable, so filers get a refund if the credit exceeds income-tax liability. Under the Senate bill, the credit remains nonrefundable.

Ohio’s local governments are still suffering from cuts in state aid. Key education investments from pre-school to financial aid for Ohioans going to college have not been made.[3] Like the House version, the Senate budget bill calls for an additional $10 million for services that protect the elderly from abuse and neglect, and a similar amount for child protective services. These are needed improvements.[4] But they do not substitute for the large-scale investments in education, infrastructure and human services that Ohio badly needs.[5]

The biggest element of the Senate tax plan is the expansion of a deduction for business income from the state income tax. Ohio taxes the profits of many businesses such as sole proprietorships and limited liability companies as they pass through to their owners, through the individual income tax. Last year, the General Assembly approved a new tax break for such business owners. Through mid-May, 315,084 taxpayers had claimed this deduction, costing the state about $230 million.[6] The average of $731 apiece underlines how unlikely it is that this tax break is going to lead to any significant job creation. The vast majority of those who are able to take advantage of this break do not employ anyone and are unlikely to do so.[7]

Since June 2013, when this tax break was approved along with a three-year, phased-in 10 percent reduction in the state income tax, Ohio has gained 42,400 jobs. This 0.8 percent increase compares with a 1.2 percent job gain in the state in the 10 months before the tax break was approved, and a 1.5 percent gain during 2012. Between June 2013 and April 2014, the number of jobs in the United States grew by 1.4 percent. There has been no surge in Ohio job creation since this tax break and the rate cut were approved. The state apparently has not kept track of any job gains resulting from the business-income tax break. In short, there is no evidence that this big new tax break has increased the number of jobs in the state.

It remains unclear how much this existing business-income deduction will cost the state. When it was approved last year, the Legislative Service Commission (LSC) and the Kasich administration both estimated it would cost more than $500 million a year, considerably more than the amount claimed to date.[8] However, taxpayers will continue filing extensions through Oct. 15, and the taxation department has not updated its previous estimate of what the tax break would cost. Between April 15 and mid-May, more than 77,000 taxpayers claimed this deduction, costing the state $82.5 million.[9] Thus, the ultimate cost of this tax break remains uncertain.

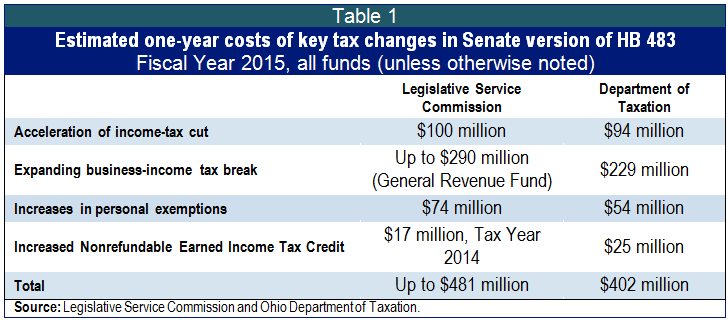

The Senate version would temporarily increase the share of business income that could be deducted from 50 percent to 75 percent, while also raising the cap on the amount of income that could be shielded from taxation from $125,000 to $187,500. This change would be effective for this tax year only. The LSC has estimated this could cost the General Revenue Fund up to $290 million in Fiscal Year 2015. The administration has estimated that the expansion will cost the state total revenue of $229 million. Neither estimate takes into account this year’s experience with the new tax break. While such estimates are inherently uncertain, in either case, this is by far the largest component of the tax changes in the Senate bill, which would also:

- Accelerate the last piece of an across-the-board, 10 percent income-tax cut approved last year, so that the final 1 percent reduction scheduled to take place in calendar 2015 instead would take place this year;

- Increase personal exemptions under the income tax. Taxpayers with Ohio adjusted gross income of $40,000 or less would see their exemptions increase from $1,700 to $2,200 starting in tax year 2014; those with income over $40,000 but less than or equal to $80,000 would see an increase to $1,950,[10] and

- Boost Ohio’s state Earned Income Tax Credit, first approved last year, to 10 percent from the current 5 percent. This credit would remain nonrefundable and capped, so that most of Ohio’s poorest earners would see very little gain from the change (see below).

Table 1 below shows estimates by the Legislative Service Commission and the Kasich administration, respectively, for the impact of each of these changes in fiscal year 2015, unless otherwise noted.

Policy Matters Ohio asked ITEP, a Washington, D.C.-based research group with a sophisticated model of the tax system, to review the key elements in the Senate bill’s tax package. ITEP analyzed the four elements in the Senate bill cited above and their impact on taxes that will be paid covering 2014. While some of the measures continue beyond then, this is a Mid-Biennium Budget bill, aimed at fiscal year 2015, the second year of the biennium (when most 2014 taxes are paid). Moreover, additional tax measures are likely to be considered as soon as later this year.[11] Thus, a focus on what the changes will mean for taxes paid on this year’s income is appropriate.

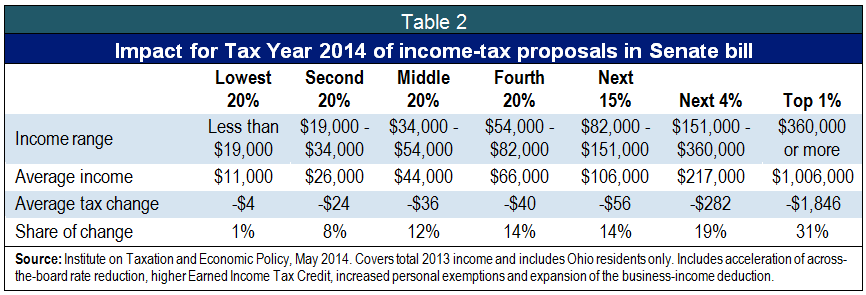

ITEP found that the top 1 percent of Ohio taxpayers, who had incomes of at least $360,000 last year, would receive an average tax cut of $1,846. By comparison, the middle fifth of Ohio taxpayers, with incomes in 2013 between $34,000 and $54,000, would see an average tax cut of $36. The lowest-earning fifth of taxpayers, who earned less than $19,000 last year, will average a cut of just $4. These estimates are based on how taxes would change from what is currently in Ohio law.

The estimates in Table 2 below show how Ohioans in different income groups would be affected by the four tax changes in the Senate bill for taxes they will pay on 2014 income. Altogether, 31 percent of the total tax cuts will go to the top 1 percent of Ohio taxpayers, and half of the tax cuts will go to the top 5 percent, those who made at least $151,000 last year:

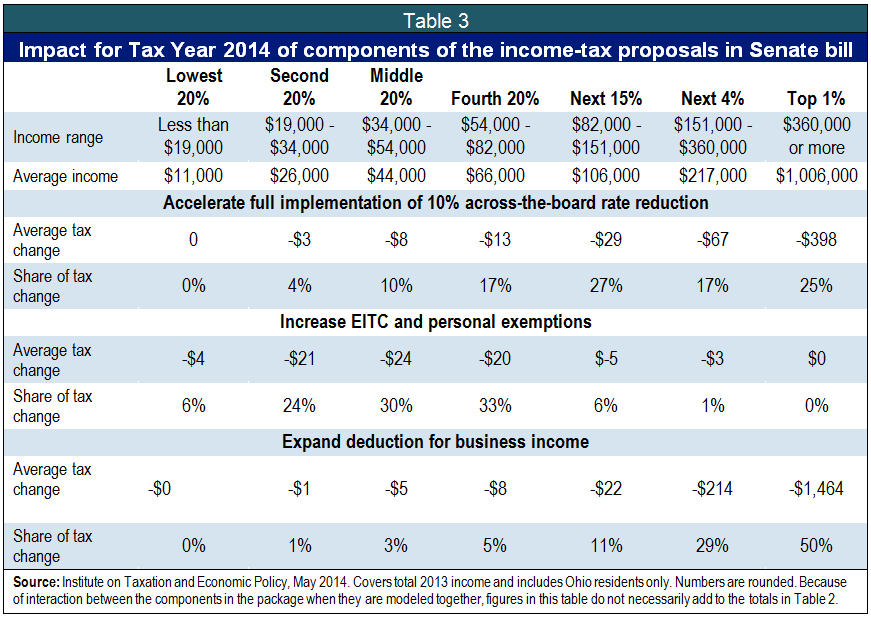

Table 3 breaks out the components of the tax changes (A separate description of the effect of the proposed increase in the state EITC follows later in the report). As the table shows, accelerating the income-tax cut and expanding the business-income deduction in 2014 far outweigh the impact of increasing the EITC and personal exemptions, the two tax changes aimed at lower- and middle-income Ohioans.

Speeding up the across-the-board rate cuts accrues mostly to the advantage of Ohio’s affluent; more than two-thirds of this will go to the top fifth of Ohio taxpayers, and the top 1 percent alone will get a quarter of the gain in 2014, averaging $398. The expansion of the business-income deduction is even more concentrated in how it flows to the most affluent Ohioans.[12] In fact, the bottom four-fifths of taxpayers will get only 8 percent of that tax cut covering 2014 income; half of it will go to the top 1 percent.

By contrast, the combined effect of boosting the nonrefundable EITC and increasing personal exemptions for those with income up to $80,000 is extremely modest. Middle-income taxpayers on average will see just a $24 cut in taxes, while those in the bottom fifth will average a cut of just $4.

The Earned Income Tax Credit

The increase in the EITC approved in the Senate version of HB 483 boosts the Ohio credit from 5 to 10 percent of the federal credit. This is a small step toward making the credit count for working Ohioans, but more is needed to truly fix Ohio’s credit. As noted, under the Senate bill, the EITC would remain nonrefundable. It also will remain capped, so that those who make more than $20,000 in Ohio Taxable Income can only receive a credit that is half of their tax bill.

The federal EITC is a carefully designed policy targeted to encourage work and make low-wage work pay. The federal credit was responsible for keeping 6.5 million Americans, and more than 3.3 million kids, out of poverty in 2012.[13] Children in households that receive the EITC are born healthier, do better in school, have higher college attendance rates, and even earn more as adults, compared with low-income children whose families don’t get the credit.[14]

Our current state tax policy is weighted against low-income families. Low-income earners are paying a higher share of their income in state and local taxes than their higher-income counterparts.[15] The most recent round of tax cuts approved by the General Assembly last year primarily benefited the top income earners in the state and exacerbated this fundamental inequality. According to a previous ITEP analysis, the top 1 percent of Ohio earners saw an average tax cut of more than $6,000, while the poorest 20 percent of earners saw an average tax increase of $12.[16]

The EITC is the most straightforward and effective way to bring greater fairness to the tax code while making work pay, but only if the credit is refundable. As a nonrefundable credit, Ohio’s EITC and the Senate-approved version can only offset income-tax liability, even though sales and property taxes are responsible for the majority of the taxes paid by working poor families. The federal EITC and the majority of state credits are refundable, meaning that if the amount of the credit exceeds the filer’s income-tax liability, the excess is returned as a tax refund.

Refundability makes the EITC effective. It is this refund that is responsible for a more significant boost in the earnings of low and moderate income working families, and for injecting fairness into the overall tax code. It is the most important design choice facing policymakers.

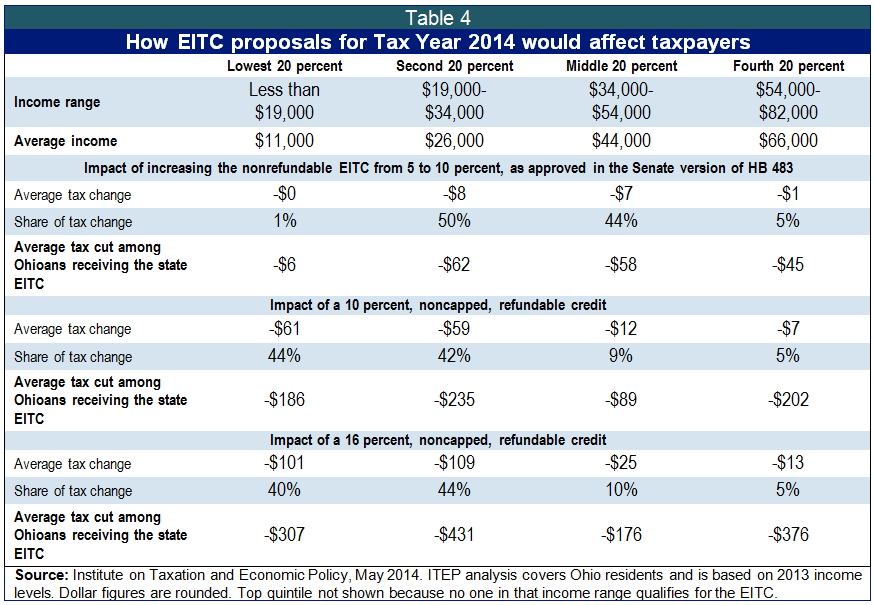

ITEP analyzed the EITC increase included in the Senate version of HB 483, along with alternatives under which Ohio would make the credit refundable and remove the current cap. Table 5 shows the results, which illustrate starkly how little the increase in a nonrefundable EITC does for the lowest-income earners.

Under the increase in the EITC in the Senate bill, taxpayers in the middle fifth of earners would see a modest average tax savings of $7 a year ($58 among those in that group who qualify for a credit). The poorest Ohioans would see almost no benefit at all; the increase in the tax credit would be so small that it would round to no change in the average tax. Only 1 percent of the total increase in the credit would go to the fifth of Ohioans who made less than $19,000 last year, and even among the small number who benefited, the average increase in the size of their credit would be just $6 a year.

By contrast, a refundable EITC provides much larger benefits, and targets them toward low-income workers. A 10 percent refundable EITC, with no cap, would provide an average of $61 a year on average to Ohioans who earned less than $19,000 last year. Fully 44 percent of the credit would go to this group, the poorest fifth of Ohioans, and among those in the group who qualified, they would see an average of $186 a year.

Nineteen states and the District of Columbia states have refundable EITCs, and they average 16 percent of the federal credit.[17] Fixing Ohio’s EITC and raising it to meet this standard would provide $101 on average annually to those who made less than $19,000 last year, and $307 to those among that group who qualify for a credit. More than four-fifths of the benefits of the increased credit would go to those who made under $34,000 last year. In short, while increasing the value of the state EITC is a worthwhile step, it does not do enough to make the credit truly count, and specifically does little to keep the lowest-income workers out of poverty.

Conclusion

The Senate tax changes, adopted without public input, will siphon more than $400 million next fiscal year into tax cuts. Most of this will go to affluent Ohioans. The biggest pieces of the tax cut, accelerating the income-tax rate cut and expanding the business-income tax deduction, are unlikely to boost Ohio jobs, based on past experience. While increasing the Earned Income Tax Credit is a step in the right direction, it needs to be made refundable to provide real benefits to the poorest Ohioans. Instead of more tax cuts like the expanded business-income tax break, we should restore and expand funding to local governments, public schools, health and human services and post-secondary education. This approach would improve communities, build opportunities for children and create the needed infrastructure for businesses.

[1] See Legislative Service Commission, Comparison Document (Including both language and appropriation changes), House Bill 483, 130th General Assembly, Appropriations/Mid-Biennium Review (FY2014- FY2015), As Reported by Senate Finance, May 21, 2014, at www.lsc.state.oh.us/fiscal/mbr130/comparedoc-hb483-sr.pdf, and email from Gary Gudmundson, Ohio Department of Taxation, May 21, 2014.

[2] See Policy Matters Ohio, “Small Solutions to Ohio’s Big Problems in Budget Bill,” at http://bit.ly/SbtX08.

[3] Patton, Wendy, “Mid-Biennium Review Should Focus on Investments, Not Tax Cuts,” Policy Matters Ohio, Apr. 1, 2014, at www.policymattersohio.org/mbr-apr2014.

[4] See Wendy Patton, “Protecting Elderly Ohioans from Abuse and Neglect,” Policy Matters Ohio, May 13, 2014, ” at www.policymattersohio.org/adult-may2014 and “Ohio’s Childcare Cliffs, Canyons and Cracks,” May 8, 2014, at www.policymattersohio.org/childcare-may2014.

[5] Some of these are outlined in Wendy Patton, “Mid-Biennium Review Should Focus on Investments, Not Tax Cuts,” Policy Matters Ohio, Apr. 1, 2014, at www.policymattersohio.org/mbr-apr2014.

[6] Conversation with Gary Gudmundson, Ohio Department of Taxation, May 20, 2014

[7] Zach Schiller, “Tax Break for Business Owners Won’t Help Ohio Economy,” Policy Matters Ohio, Apr. 2, 2013, at www.policymattersohio.org/tax-breakpr-apr2013. A recent national study by researchers at the U.S. Treasury Department found that only 11 percent of taxpayers reporting business income – and 2.7 percent of all income-tax payers – own a bona fide small business with employees other than the owner. See Matthew Knittel, Susan Nelson, Jason DeBacker, John Kitchen, James Pearce, and Richard Prisinzano, “Methodology to Identify Small Businesses and Their Owners,” Office of Tax Analysis, U.S. Department of Treasury, August 2011, Table 8, at http://1.usa.gov/1kbDNoT.

[8] The LSC estimated the new tax break would cost $543 million to the General Revenue Fund in FY 2015, while the administration estimated the cost at $556 million to all funds that year. See Phil Cummins, LSC Greenbook, Analysis of Enacted Budget – Department of Taxation, Sept. 2013, p. 25, at www.lsc.state.oh.us/fiscal/greenbooks130/tax.pdf and Office of Budget & Management, Estimates of HB 59 Tax Reform Package.

[9] See Gongwer News Service Ohio Report, “Taxpayers Slow to File for New Small Business Tax Cut,” Vol. 83, Report #76, April 21, 2014, and conversation with Gary Gudmundson, Ohio Department of Taxation, May 20, 2014.

[10] Gov. Kasich earlier this year proposed increases in the personal exemption for these two groups. His proposal called for larger increases – to $2,700 and $2,200, respectively.

[11] Pelzer, Jeremy, “Ohio Senate Approves Bill to Expand Income, Business Tax Cuts,” Northeast Ohio Media Group, May 21, 2004, at www.cleveland.com/open/index.ssf/2014/05/ohio_senate_approves_bill_to_e.html. The article notes that Kasich Administration spokesman Rob Nichols “said that Kasich’s proposed 8.5-percent across-the-board income-tax cut, which would be paid for by commercial activity, oil and gas, and tobacco tax hikes, is “still on the table” and will “be part of the longer discussion.””

[12] ITEP’s estimates are generated from their sophisticated microsimulation tax model based on business income reported on federal income tax returns. Modeling an expanded business-income deduction does not depend on data regarding how many taxpayers have claimed the existing deduction.

[13] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Policy Basics, available at www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=2505, accessed May 20, 2014, based on analysis of Census Bureau data.

[14] Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, and Arloc Sherman, Earned Income Tax Credit Promotes Work, Encourages Children’s Success at School, Research Finds, Center of Budget and Policy Priorities, April 15, 2015, available at www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3793, accessed May 20, 2014. “Poverty” is defined as a family with an income below the threshold for poverty as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.

[15] See, The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Who Pays? Fourth Edition, Ohio fact-sheet, January 2013, at http://www.itep.org/whopays.

[16] Patton, Wendy, Zach Schiller and Piet van Lier, “Overview: Ohio’s 2014-2015 Budget,” Policy Matters Ohio, Oct. 3, 2013, Table 1, p. 5, at www.policymattersohio.org/budget-oct2013.

[17] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Improving Tax Fairness with a State Earned Income Tax Credit,” May 2014, at www.itep.org/pdf/eitc2014.pdf.

Tags

2014Budget PolicyHannah HalbertRevenue & BudgetTax ExpendituresTax PolicyZach SchillerPhoto Gallery

1 of 22