Medicaid expansion benefits Ohio

October 21, 2014

Medicaid expansion benefits Ohio

October 21, 2014

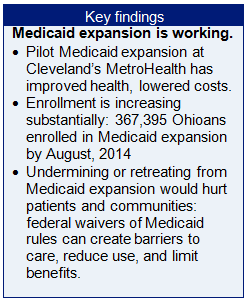

Download summary (1pg)Download report (7pp) Press release Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of waiver programsMedicaid expansion in Ohio delivers better care, broadens access. Ohioans see improved health outcomes, lower costs; providers get reliable pay for delivery; Ohio economy sees $2.5 billion boost Policy Matters Ohio reports on progress in Ohio's Medicaid Expansion, and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analyzes problems in Indiana's waiver program.

Better health, better care, controlled costs

Wendy Patton Ohio’s Medicaid program, expanded to provide coverage for working poor adults, is already showing positive outcomes. Early outcomes demonstrate the benefits of broad access to a doctor’s care: better health, better care, and lower costs. Ohio’s Medicaid program provides a good base to build on in the upcoming state budget for fiscal years 2016 and 2017.

Ohio’s Medicaid program, expanded to provide coverage for working poor adults, is already showing positive outcomes. Early outcomes demonstrate the benefits of broad access to a doctor’s care: better health, better care, and lower costs. Ohio’s Medicaid program provides a good base to build on in the upcoming state budget for fiscal years 2016 and 2017.

The federal government has waived traditional Medicaid rules for the Medicaid expansion population – low-income adults – for demonstration projects in four states. Enrollees will pay for services through premiums or co-pays, in some cases, through a mechanism like a health savings account. While demonstration projects approved so far have not strayed far from traditional rules, some elements could limit access to care. For instance, studies have found charging fees for Medicaid services can reduce participation in the program, which works against program objectives.

This brief reviews benefits from expanding Medicaid health care to low-income working adults; examines outcomes since January 2014, when Ohio offered broader Medicaid coverage, and finds that Ohio’s straightforward approach is already showing positive outcomes. Legislators need to focus on what works best in Ohio for Ohioans in the upcoming budget debates.

Medicaid Expansion

Medicaid provides insurance and access to health care to 24 percent of Ohio’s adults and children. The states administer this federal program. Before the Affordable Care Act (ACA), public health care coverage through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) covered children, aged, blind and disabled individuals and pregnant women, all of low-income or from low-income families. Some states – including Ohio - covered a portion of low-income parents with minor children. With the Medicaid expansion of the ACA, working poor adults earning up to 138 percent of poverty ($16,105 a year for a single person, which is $7.95 per hour for just under 40 hours per week) became eligible for Medicaid coverage, regardless of whether they have children. In Ohio, more than 367,395 newly eligible adults signed up for coverage between January 1, 2014 and August of 2014.The federal government is paying the entire cost of expanding Medicaid to these adults through the end of 2016. The federal share will fall to 95 percent in 2017 and then to 90 percent by 2020, and remain at that level.[1] Ohio will continue to get billions of federal dollars to provide care to this population. In the fall of 2013, the state Controlling Board, a largely legislative committee that oversees certain financial matters, approved acceptance of $2.5 billion federal dollars for this use. The legislature will debate whether to continue to accept federal funds and provide health care to these Ohioans in the two-year state budget for fiscal years (FY) 2016 and 2017, which begin July 1, 2015.

Initial outcomes of Ohio’s Medicaid expansion

Cleveland’s MetroHealth System provided Medicaid coverage to uninsured poor adults months before the state expanded eligibility. Analysis of nine months of data shows the pilot expansion achieved better care, improved health outcomes and reduced cost.[2] Emergency department visits dropped by 60 percent and primary care visits rose by 50 percent.[3] Care also cost $150 less a month per patient than MetroHealth officials had originally estimated.[4] Finances at the hospital improved as well. Charity care dropped by half, going from $268 million in 2012 to $132 million in 2013. Standard & Poor's, Moody's and Fitch Ratings boosted ratings for the hospital in 2014.[5]Statewide enrollment for Medicaid expansion started in Ohio in January. Ohio State University’s Wexner Medical Center reported a 19 percent drop in uninsured care between July 2013 and June 2014. Mount Carmel Health System saw a 10 percent decline in uninsured patients during the first half of 2014 compared to the last six months of 2013. Officials attributed the drop in uninsured patients to the Medicaid expansion.[6]

John Rusnaczyk, Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer of St. Vincent’s Hospital in Cleveland, notes that the share of Medicaid enrollees in the hospital’s payer mix has risen by 19 percent and the cost of charity care has gone down. This is good for hospital finances, but cuts in other state and federal funds loom. “The good news is, more people are getting care,” says Rusnaczyk. “If the state Medicaid expansion is not renewed in the coming budget, we could see significant negative impact if other program cuts are not re-visited.”[7]

The Cleveland Clinic has seen a substantial increase in its Medicaid volume. In response,, the hospital expanded primary care outreach and care coordination efforts with Medicaid patients at their family health centers. The Cleveland Clinic Integrated Care Model, which focuses on delivering the right care at the right time and place for each patient, is at the heart of the initiative. “This has the potential to benefit patients who have recently obtained coverage through expanded Medicaid and the healthcare exchanges, many of whom have not had regular access to preventive care for some time,” said Megan Pruce, Director of Public Relations. “We are in the process of evaluating how our approach to this population should evolve over time, as patients transition from a state of new patient evaluation and intervention, build regular relationships with their neighborhood providers, and begin to focus on wellness and health maintenance.”[8]

Berger Health System of Circleville, Ohio has also seen positive results from Medicaid expansion. Richard Filler, Chief Financial Officer, has analyzed trends for self-pay (uninsured) patients. From January through June 2014, Berger Health System saw a 30.4% decline in the number of uninsured patients. Bad debt for the hospital decreased as patients became insured under Medicaid.” [9]

Community health centers across the state are seeing benefits of Medicaid expansion. “We are seeing more patients who have Medicaid coverage and less who can’t pay,” said Randy Runyon, President and CEO of the Ohio Association of Community Health Centers. “We therefore have more resources to invest in strengthening the system and providing better, more comprehensive care.”[10] Community health centers are important partners in the health system. Even under expanded Medicaid, they serve those who remain uninsured or who are rejected by private physicians. Community health centers cannot limit the number of uninsured or Medicaid patients they treat.

Medicaid expansion program structure

Ohio’s Medicaid program gets good reviews in national studies. Medicaid coverage allows people to see a doctor and to get needed health care they could not otherwise obtain.[11] Ohio’s Medicaid program provides service and quality of care similar to that of private pay care.[12]Most states that elected to expand Medicaid simply amended their Medicaid state plans to extend coverage to the new adult eligibility group. This is what Ohio has done. Others chose a weaker version of the federal program, seeking a waiver of Medicaid rules for the expansion population, in some cases to overcome opposition in the state legislature to a straightforward expansion.

Section 1115 of the Social Security Act authorizes the Secretary of the federal Department of Health and Human Services to waive state compliance with certain federal Medicaid requirements. Expansion waivers must articulate a clear demonstration purpose that promotes the objectives of Medicaid and conforms to the following:[13]

- Expansions must fully extend Medicaid to adults up to 138 percent of the poverty line in order to get the enhanced matching rate for the expansion population.

- Medicaid expansion enrollees served under waiver in the health care marketplace – through private health insurers – remain Medicaid beneficiaries. As such, states must ensure that beneficiaries have access to the same benefits as they would under traditional Medicaid.

- Medicaid expansion enrollees may not be not subject to higher cost-sharing charges than if they were served under a traditional Medicaid plan. [14]

The basis for improving health and controlling cost under the ACA is expanded access to preventive care and predictable payment for providers. A substantial body of research finds requiring a financial contribution decreases participation in health care and, in some cases, increases unpaid emergency treatment.[15] Cost increases have a disparate impact on low-income individuals and families, who must dedicate a larger share of their incomes to other basic needs, such as food and shelter.

The Rand Health Insurance Experiment, conducted between 1971 and 1986, found that although it had little impact on the average person, cost sharing adversely impacts patients who are ill or poor. Free care led to improvements in hypertension, dental health, vision, and selected serious symptoms among the sickest and poorest patients.[16] The study found copayments led to a much larger reduction in use of medical care by low-income adults and children than by those with higher incomes. Families cut care that researchers called “effective” as well as care labeled "less effective." Low-income families lost far more because of financial contribution requirements than middle and high-income people. [17]

State-level studies assessing the impact of financial requirements on health care use by low-income people over the past decade corroborate these findings:

- Wisconsin imposed premiums of 3 percent of household income on adults in the state’s Medicaid program in July 2012. Three months later, nearly a quarter of this group was dis-enrolled from the program because of non-payment.[18]

- Physicians at Minneapolis’s main public hospital surveyed patients attending medical clinics in mid-2004. Of 62 patients covered by Medicaid or medical assistance, more than half (32) reported that they had been unable to get their prescriptions at least once in the last six months because of copayments of $3 for brand name drugs or $1 for generic drugs. Eleven of the patients who failed to get their medications had 27 subsequent emergency room visits and hospital admissions for related disorders. For example, patients with high blood pressure, diabetes or asthma who could not get their medications experienced strokes, asthma attacks and complications due to diabetes. [19]

- Over a decade ago, Oregon raised premiums for adults with incomes below the poverty line. Premiums ranged from $6 per month for people with no income to $20 per month for people with incomes at the poverty line. Nine months later, nearly half had disenrolled. About three-quarters of those who lost coverage became uninsured.”[20]

Low-income families live on tight budgets and unexpected expenses cause hardship. Some states have instituted financial contributions and then waived them for some particularly hard-pressed families. This is a puzzling approach, because the entire target population, all below 150 percent of the poverty level, experiences hardship. Some states have found the cost of collection and monitoring exceeds the value of premiums. Virginia imposed a $15 per child per month premium on low-income families but eliminated it when the state found nearly 4,000 children were at risk of losing coverage for nonpayment and a study indicated that the state was spending $1.39 in administrative cost to collect every $1 in premium.[24]

In approving waivers for the Medicaid expansion population, the federal government has kept states from straying too far from the general objective of the Medicaid program: to provide needed health care for people who can’t afford such services. To date, states have not been allowed to:[25]

- Disenroll people with incomes of less than poverty for failure to pay.

- Charge people more than existing Medicaid rules allow.

- Limit certain Medicaid benefits.

- Condition Medicaid eligibility on work requirements or job search activities.

Summary and conclusion

Ohio’s health care system, like that of other states, shows initial benefits from Medicaid expansion. Cleveland’s MetroHealth System, an early pilot that provided coverage to poor adults, caused emergency room visits to drop and doctor’s visits to rise. Patients were healthier. The health system’s finances improved. Other Ohio health systems are beginning to see positive outcomes from the statewide Medicaid expansion. The system seems to be working and producing needed results.

The federal government is allowing experimentation in how states provide services to the Medicaid expansion population. Common features in the four demonstration projects could diminish participation and thus reduce positive health outcomes. Financial contributions can be burdensome to people with low incomes. Many studies have found asking the poor to pay for health care causes them to disengage from the health care system. Complex administrative structures like health care accounts with different rules for different enrollees may be confusing to low-income families. Families may fall in and out of co-payment brackets with changes in seasonal hours or shifts. Low-income people and families often lack money for stable housing and move frequently, causing them to miss quarterly statements and bills. This could lead to loss of benefits or even collectible debts.

As Ohio moves into state budget deliberations, legislators should prepare to build on Ohio’s health care investments and strengths. Ohio can continue to be a leader and benefit from the changes of health reform, or we could join states that are losing out. States that have not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act are losing billions of federal dollars. Ohio would lose billions, too, if legislators chose to reject the expansion already under way. This would hurt individuals, families, and the health care system that serves us all.

Ultimately, national health care reform is about better health for all Americans – including those of moderate and low income – and strengthening the health care system that serves all Americans. Ohio’s Medicaid expansion plan is doing well. Ohio should stay the course.

[1] In Ohio, the federal government picks up 63.02 percent of the cost of Medicaid for medical services of covered groups other than the Medicaid expansion population and 74.11 percent for the medical care of children of low-income families.

[2]Dr. James Misak, Associate Director of Family Health for Metro Health System, panel discussion at the Columbus Metropolitan Club,10/1/2014.

[3] Sarah Jane Tribble, “A Hospital Reboots Medicaid To Give Better Care For Less Money,” NPR, Kaiser Health News and WCPN, 8/5/2014 at http://sarahjanetribble.com/2014/08/03/306/

[4] Interview with John Corlett, Government Affairs Director at MetroHealth, 8/22/2014.

[5] Stephen Koff, “Obamacare is helping Ohio hospitals, but several factors have yet to play out,” The Plain Dealer, 9/27/2014 at http://www.cleveland.com/open/index.ssf/2014/09/obamacare_is_helping_ohio_hosp.html

[6] Ohio Health Policy Review, http://www.healthpolicyreview.org/daily_review/ohio_hospitals/, 8/22/2014.

[7] Telephone interview with John Rusnaczyk, Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer, St. Vincent’s Hospital, Cleveland.

[8]E-mail from Megan Pruce, Director of Public Relations, Cleveland Clinic, 10/14/2014.

[9]e-mail from Richard Filler, Chief Financial Officer, Berger Health Systems, 10/15/2014.

[10] Interview with Randy Runyon, President and CEO of the Ohio Association of Community Health Centers, 9/26/2014.

[11] See Nakela Cook et al. “Access to Specialty Care and Medical Care Services in Community Health Centers.” Health Affairs, V.26, no. 5 (2007): 1459-1468 http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/26/5/1459/T2.large.jpg.

See also United States Government Accountability Office, Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services, “Medicaid: States Made Multiple Program Changes, and Beneficiaries Generally Reported Access Comparable to Private Insurance.” 11/2012. (GAO-13-55.) http://gao.gov/assets/650/649788.pdf

[12] A national study comparing quality of hospital care between patients with Medicaid and those with private insurance found no difference between Medicaid and private pay for two of three medical conditions studied for Ohio and only a one-percentage-point difference for the third. Ohio’s scores were always above the national Medicaid average. William Hayes, Op. Cit., (drawing on Joel S. Weissman, Christine Vogeli, and Douglas E. Levy. “The Quality of Hospital Care for Medicaid and Private Pay Patients.” Medical Care. 5/2013; 51:389-395.)

[13] Jesse Cross-Call and Judith Solomon, “Approved Demonstrations Offer Lessons for States Seeking to Expand Medicaid Through Waivers,” Center for Budget & Policy Priorities, 8/20/2014, at http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=4190

[14]In the United States, there are two ways that people with insurance pay for health care: through premiums, paid on an ongoing basis to cover the cost of care, and through other cost-sharing mechanisms like co-pays or deductibles, paid at the doctor’s office or hospital when care is received.Traditional Medicaid plans may be seen as a public service without cost, but within certain guidelines, more than 40 states imposed some form of charge on Medicaid recipients in 2013. See Cross-Call and Solomon, Center for Budget & Policy Priorities, Op.Cit.

[15]“Premiums and Cost-Sharing in Medicaid: A Review of Research Findings,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2/2013 at http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/8417.pdf ; Samantha Artiga and Molly O’Malley, “Increasing Premiums and Cost Sharing in Medicaid and SCHIP: Recent State Experiences,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured at http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/increasing-premiums-and-cost-sharing-in-medicaid-and-schip-recent-state-experiences-issue-paper.pdf; Leighton Ku and Victoria Wachino, “The Effect of Increased Cost-Sharing in Medicaid.” July 2005 at http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=321

[16] “The Health Insurance Experiment,” The Rand Corporation at http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9174.html

[17] The Rand study found that copayments did not significantly harm the health of middle- and upper-income people but did lead to poorer health for those with low incomes. The study found that among low-income adults and children, health status was considerably worse for those who had to make copayments than for those who did not. (In the RAND study, low income was defined as the lowest third of the income distribution, which is roughly equivalent to being below 200 percent of the poverty line. This is considerably higher, of course, than adult threshold for Medicaid even with its recent expansion) For example, copayments increased the risk of dying by about 10 percent for low-income adults at risk of heart disease - Joseph Newhouse, Free For All? Lessons from the Rand Health Insurance Experiment, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996, cited in Leighton Ku and Victoria Wachino, “The Effect of Increased Cost-Sharing in Medicaid.” July 2005 at http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=321

[18] State of Wisconsin Department of Health Services “Wisconsin Medicaid Premium Reforms: Preliminary Price Impact,” Table 4: Premium enrollment impacts. Findingshttp://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/P0/P00447.pdf

[19] Melody Mendiola, Kevin Larsen, et al. “Medicaid Patients Perceive Copays as a Barrier to Medication Compliance,” Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN, presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine national conference, May 2005 and American College of Physicians Minnesota chapter conference, Nov. 2004.

[20] Center for Budget and Policy Priorities and Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, Letter to Secretary Kathleen Sibelius regarding proposals for the Iowa Marketplace Choice Plan and Iowa Wellness Plan, September 26, 2013 at http://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/IA-Longer-Comments-Final.pdf

[21] The most unbanked places in America, Corporation for Enterprise Development at http://cfed.org/assets/pdfs/Most_Unbanked_Places_in_America.pdf

[22] 2011 FDIC National Survey of Banked and Underbanked Households, Appendix H, Table H-1 2011 Household Banking Status by State https://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/

[23] 2011 FDIC National Survey of Banked and Underbanked Households, Op. Cit., In 2009, there were 319,000 unbanked households in Ohio, or 6.9 percent of households. Id., Table H-2 2009 Household Banking Status by State

[24] Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services memo, 5/15/2002; see also, L. Summer & C. Mann, “Instability of Public Health Insurance Coverage for Children and Their Families: Causes, Consequences, and Remedies,” The Commonwealth Fund (June 2006). Cited in Tricia Brooks, Handle with Care: How Premiums Are Administered in Medicaid, CHIP and the Marketplace Matters, Georgetown University Center for Families and Children at http://www.healthreformgps.org/wp-content/uploads/Handle-with-Care-How-Premiums-Are-Administered.pdf

[25] Cross Call and Solomon, Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, Op. Cit.

Tags

2014Budget PolicyMedicaidRevenue & BudgetWendy PattonPhoto Gallery

1 of 22