Taxing Fracking: Proposals for Ohio's severance tax

May 10, 2012

Taxing Fracking: Proposals for Ohio's severance tax

May 10, 2012

Press releaseDownload reportDownload executive summaryThis report explores how revenue from a fracking tax could bolster vital public services if it is not used to finance income tax cuts that would mostly benefit wealthy Ohioans, as Gov. John Kasich has proposed. The Ohio General Assembly should consider an adequate tax on oil and gas extraction to help restore local jobs, schools and services and assist communities impacted by drilling.

The Kasich Administration has proposed strengthening the severance tax, but the General Assembly won’t have the debate. Job losses mount and local economies falter as the result of billions cut in the state budget. There is urgent need to raise revenues to restore jobs and services and help impacted communities with up-front costs of drilling. Every day the oil and gas extracted from Ohio’s land will never be replaced, yet legislators are not even talking about keeping a share of that value to build opportunity for Ohio’s future.

Current severance tax

Ohio’s severance taxes are among the lowest of all energy states. Regardless of the price for a barrel of oil, the driller pays a dime per barrel for the severance tax and another dime in a conservation fee. Whether oil is selling for $35 or $150 per barrel, Ohio is getting just 20 cents. The severance tax on natural gas is also low, at 3 cents (including a half-cent conservation fee) per thousand cubic feet (mcf). Whether natural gas is selling for $10.00 or $2.28 per mcf, Ohio is getting just 3 cents.

Kasich’s proposal

Gov. John Kasich proposes raising rates on fracked oil and natural gas liquids to 4 percent with a tax break that lowers it to 1.5 percent for up to 24 months. Fracked dry gas would be taxed at 1 percent. A small share of the revenues – no more than what would be raised at today’s low rates – would be used for oversight and regulation of the industry. The rest would be given back in income tax cuts.

Rates should be higher

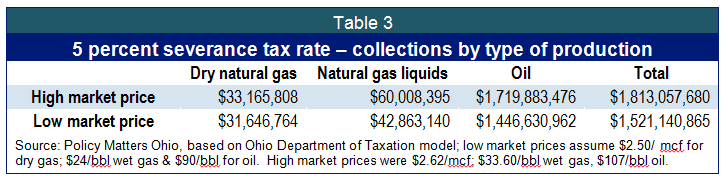

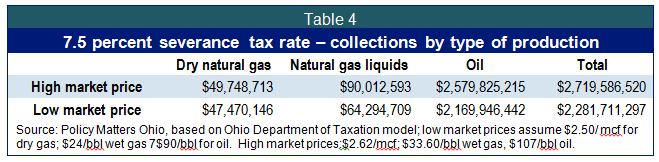

Kasich’s proposal could raise up to a billion dollars over four years. A 5 percent severance tax rate (on all production, no loopholes) could generate up to $1.8 billion over the same time period. An additional 2.5 percent could raise another $900 million. None of this is enough to restore the nearly $2 billion cut from Ohio’s K-12 schools and the $1 billion cut from communities for services ranging from pothole repair to senior centers. But a severance tax at 5 percent or 7.5 percent could start to restore jobs and investment in local communities and local services.

Tax loopholes should be eliminated

Kasich’s proposal includes tax loopholes that allow frackers to recover the costs of drilling. The tax break lowers the severance tax rate on oil and natural gas liquids for the first year, and up to another 12 months, from 4 percent to 1.5 percent. This loophole may cost as much as $603 million over four years.

Tax cuts are the wrong use

The state has lost 275,000 jobs since 2005, when the Ohio legislature cut the state income tax by more than 20 percent. Kasich proposes using severance tax revenues for further income tax cuts, an approach that has not created jobs in the past. Furthermore, most families won’t benefit from Kasich’s proposed tax cuts, which would average only $42 for median-income Ohioans, but would give $2,300 to the top 1 percent, those averaging incomes of $321,000 a year. Revenues should be used instead to keep cops on the beat, firehouses open, teachers in the classroom and to maintain vital services that families depend on, like senior centers, community mental health, trash pick-up, clean water and pothole repair.

Local communities impacted by drilling face a treadmill of costs

The Kasich proposal for local impact fees would require well owners to make an up-front payment of $25,000 (based on estimates of needs related to roads) but would require that fee to be paid back. This ignores not only many costs associated with drilling activity, which range from roads to health care, schools, emergency services, and waste disposal, but also the recurrence of drilling impacts related to repeated well stimulation. Horizontal drilling has unusual costs that recur as the well is stimulated over and over: swarms of workers, truckloads of supplies, well preparation, wastewater disposal or recycling. The “treadmill” of drilling and fracking activity means heightened and more continuous industrial impacts on rural infrastructure and stress on community services. As a result, communities impacted by drilling will need resources on an ongoing basis. The severance tax is the tool of public finance used to assist impacted communities in states with significant energy production. For example, Colorado provides 63 percent of its severance tax to local government. Montana provides 39 percent; North Dakota, 11 percent; Wyoming, 35 percent.

Drillers are going to drill if the resource is there

The oil and gas industry is vociferous in opposition to Kasich’s proposal. But imposition of the tax won’t discourage oil companies that have spent billions on land leases. The leases already create a contractual obligation to drill. Leases expire after three to five years and although they may be renewed, there is a cost to renewal.

Recommendations

- The tax rate on all oil and gas needs to be higher than 4 percent. A 5 percent severance tax rate would help restore local jobs, schools and services and assist impacted communities. An additional 2.5 percent should be used to create a permanent fund dedicated to economic recovery from the drilling and to provide for environmental risk.

- There should be no tax breaks. Loopholes for cost recovery such as those in Kasich’s proposal were first used as horizontal drilling and pressurized extraction were under development. Other states have such breaks, but they reflect years of legislative fights that oil company lobbyists won. There is no reason to adopt the outcomes of those battles in a new tax structure in Ohio.

- All production from the well – dry gas, wet gas and oil – should be taxed at the same rate. Natural gas may be low in cost now, but it has been high in the recent past. The proposed severance tax fee is based on percentage, so when taxation falls with market value.

- Funds should not be used for tax cuts. Revenues should be used to restore services, help local communities with drilling costs and start building a diversified economy when wells run dry.

Introduction

The severance tax is used to ensure that the wealth of the land, mined and sold by private interests, provides lasting benefits to the people of a region or state. As oil and gas drilling expands in Ohio, Gov. John Kasich has proposed boosting the severance tax, a good idea. However, the proposed rates are too low; tax breaks would erode collections yet don’t interest a defiant industry; and the complexity mirrors states where energy taxes have been distorted by decades of legislative wrangling. There’s much to debate, but Ohio’s House of Representatives, reluctant to even talk about taxes, stripped the proposal from the budget bill it passed in April and sent over to the Senate.

Last year’s budget cuts undermined the economic recovery by causing thousands of layoffs in schools and local government. An adequate severance tax could help restore jobs, lower class size, open closed senior centers and turn streetlights back on. But even if the legislature would consider it, Kasich wants to use the money for more tax cuts, and tax cuts that favor the wealthy – again. Middle-income households would get an average of just $42 per year under the Kasich proposal; wealthy households averaging $321,000 in income would get $2,300.[1]

Adequate taxation of mineral wealth is a responsible recommendation the legislature should embrace, the sooner, the better. A natural resource boom doesn’t last. A severance tax provides for the present and prepares for a future after the minerals are depleted. The oil companies’ land leases to drill expire within 3 to 5 years: now is the time to act.

Depending on market prices, a 5 percent severance tax rate on oil and gas production – with no loopholes – could yield up to $1.8 billion over four years for job creation, economic recovery and restoration of investment in Ohio.[2] Investment funds rise to $2.7 billion with a rate of 7.5 percent. This could help repair some – but not all – of the damage of the slashing of $2 billion cut to schools, the $1 billion cut to communities, and a $500 million cut to instruction in colleges and universities. Revenues should be used to restore jobs, local economies and services and to help communities impacted by the drilling boom. Prudent leadership would use some of the money for a permanent fund to lay the groundwork for a strong, diversified economy after the drillers are gone, and to establish a cushion in the case of liability if the air, water and/or soil are poisoned by drilling.

What is a severance tax?

Citizens and businesses alike pay taxes to support civil society. The severance tax is different: it is the tax that allows the people to share in the wealth of natural resources removed forever from the land. In developing nations, valuable minerals and natural resources may be abundant and vigorously extracted, but the people often remain poor. In The United States, the wealth reserved through the severance tax is typically used to boost opportunity: to strengthen schools, keep tuition low, build roads and bridges, plan for a diversified economic future, and protect communities from environmental degradation that is often a part of the extractive process.

What is the current severance tax on natural gas and oil in Ohio?

Ohio’s severance taxes on oil and gas are among the lowest of states that produce energy.[3] Regardless of the selling price for a barrel of oil, the driller pays a dime per barrel for the severance tax and another in a conservation fee. Whether oil is selling for $35 or $150 per barrel, Ohio is getting just 20 cents. The severance tax on natural gas is also low, at 3 cents (including a half cent conservation fee) per thousand cubic feet (mcf). Whether natural gas is selling for $10.00 or $2.28 per mcf, Ohio is getting just 3 cents.

Kasich’s proposal for new severance taxes

The Kasich Administration’s proposal is complex, establishing new definitions based on type of well and setting taxes based on these new distinctions. It creates a distinction is between wells drilled with a horizontal bore and those with a vertical bore (“non-horizontal"). It distinguishes between dry natural gas and the more valuable natural gas liquids (‘wet gas’). Oil produced from conventional (non-horizontal) wells would see no change in severance tax. Most current natural gas wells would be exempted from any severance tax on production, wet or dry. The owner of a horizontal well would pay one severance tax rate on natural gas liquids and oil, and a different rate on dry natural gas.

Natural gas wells producing dry or “pipeline quality” gas

Kasich’s proposal would tax wet gas and dry gas separately.[4]

- Non-horizontal wells producing ‘dry’ natural gas and producing less than 10,000 cubic feet per day (referred to as 10 MCF) per day would no longer be taxed. This exempts 44,500 wells from the severance tax, 90 percent of Ohio’s current natural gas wells.[5]

- Wells producing more than 10 MCF daily either through conventional wells or horizontal wells would be taxed at 1 percent of value with a cap of 3 cents per MCF.[6]

- Wells that produce through horizontal drilling will be taxed at 1 percent of value even if production is less than 10 MCF per day.

- Value will be based on metered volume of the gas in the quarter multiplied by the average of the daily closing spot "Henry Hub" prices for that quarter listed on the New York Mercantile Exchange.

Natural gas wells producing “wet’ gas

Some of the natural gas coming out of a well condenses into liquids that are processed into butane, ethane, propane, and others and used in chemical and plastics manufacturing. Wet gas would be taxed at the same rate as oil under the Administration’s proposal.

- Wet or liquid natural gas from a horizontal well would be taxed at 4 percent of value.

- Value is based on metered volume multiplied by the average of the daily closing spot "Mont Belvieu" price for the condensate that quarter listed on the New York Mercantile Exchange.

- Producers of wet gas through horizontal wells may apply for a reduced rate of 1.5 percent during the initial 12 months of production, with extension if necessary up to 24 months, to recover the costs of drilling.

- Wet gases produced from non-horizontal wells would be exempted from the severance tax.

Oil wells

- Oil from horizontally drilled wells would be taxed at a rate of 4 percent of value.

- Value is based on metered volume multiplied by the average of the daily closing spot "WTI Cushing" (oil) prices for that quarter listed on the New York Mercantile Exchange.

- Producers of oil through horizontal wells may apply for a reduced rate of 1.5 percent during the initial 12 months of production, with extension if necessary to up to 24 months, to recover the costs of drilling.

- Non-horizontal oil wells would be taxed at the existing severance tax rate (10 cents per barrel for a severance tax and 10 cents per barrel for a conservation fee).

Appendix B contains tables that compare features of Ohio’s proposed system to other energy states. The application of the tax specifically to natural gas liquids is a good feature of severance taxes in many states, and the Kasich administration is right to adopt this feature. Other aspects, like the tax breaks for cost recovery, immediately accede to the legislative victories of oil and gas lobbyists in other states and in earlier times. These concessions don’t acknowledge the fact that drillers who want to extract from Ohio’s shale-based resources will probably use horizontal drilling.

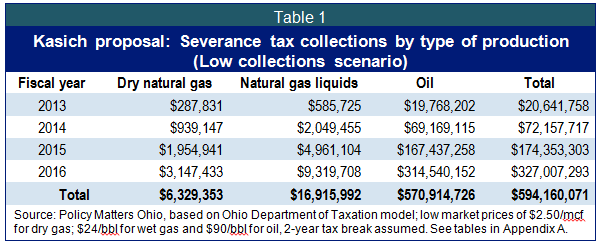

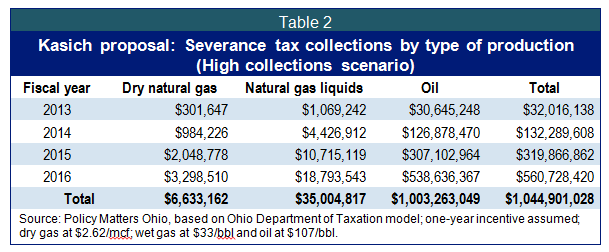

How much money would the proposed severance tax raise?

The Kasich administration’s proposal will produce around $600 million to $1 billion dollars over the next four years depending on prices and use of tax breaks, according to simulations by the Ohio Department of Taxation.[7] At the lowest level, assuming low market prices for oil and gas and 24-months of tax breaks on oil and natural gas liquids, revenue collections under the administration’s proposal would raise $594 million over four years (Table 1; see Appendix A for prices, production and comparisons). This would replace only a little more than half the funds cut from local government for safety, street repair, and other essential services – in the two-year state budget. With higher market prices and use of the cost recovery tax break for only 12 months, the Kasich proposal would raise more than $1 billion over four years (Table 2).

Table 1 illustrates collections of severance tax under the Administration proposal if prices for oil and gas are less than they are at present. Revenues come primarily from production of oil. Although the revenues from natural gas over the next four years could be very helpful,[8] they are minimal compared to the estimates for oil. The cost recovery tax break, which brings the severance tax rate down to 1.5 percent instead of 4 percent, is assumed here to be used for the maximum time allowed, 24 months, and low market prices are assumed. Revenues are adjusted for fiscal year collections, which lag the calendar year by three quarters.[9]

The highest production of oil and gas happens in the first two years of production, so the cost recovery tax break can shelter income during peak production. [10] The price tag under the Kasich proposal could be as high as $603 million.[11]

Table 2 shows the high estimate revenue collections under the Kasich proposal. This scenario assumes higher market prices and only 12 months of the cost recovery tax break.

Table 3 shows that if all production – oil, dry gas, wet gas – were taxed at a severance tax rate of 5 percent rate, with no tax breaks, $1.5 to $1.8 billion in revenues could be generated in the next four years, depending on market prices. (See Appendix A as well.)

Table 4 shows that at a tax rate of 7.5 percent on all production, with no incentives, $2.3 billion to $2.7 billion could be raised over four years time.

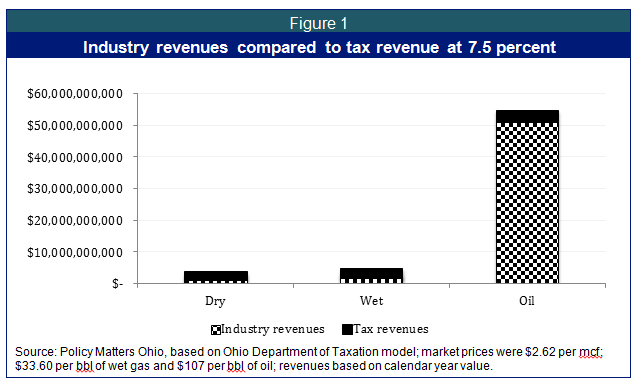

The value of oil and gas production from fracking in Ohio is projected to total between $45 and $54 billion dollars over four years. (See Appendix A, Tables 1-A and 2-A, for estimates of number of wells per year and annual production for the first 5 years of a well.) Figure 1, next page, shows that tax collections, at 7.5 percent, would represent a small share of total value.

Gongwer Ohio quotes Gov. Kasich saying he could not “conceptualize or even imagine” why legislators would seek funding to restore local services and schools cut in his biennial budget.”[12] In fact, virtually every community has been hurt by budget cuts in the past few years, with more harm on the horizon. Children’s classrooms have become more crowded, trash collections are now bi-weekly in some communities, police and fire protection has been cut, potholes are not repaired and senior centers have been closed. New revenues could be used to replace those lost, to ensure that Ohio can provide the basics that have historically made this a good place to do business, raise a family, and be part of a community.

The oil and gas industry is vociferous in its opposition to the Kasich proposal. This is not unusual, as business usually fights taxation. But imposition of the tax won’t discourage oil companies that have spent billions on land leases. The leases already create a contractual obligation to drill, and expire after three to five years; although they may be renewed, there is a cost to renewal. Crain’s Cleveland Business interviewed attorneys representing landowners in Ohio’s growing oil patch, and concluded: “As a result of those potential costs, lawyers say, even if the state raises the taxes it collects on the production of Ohio's gas and oil, the energy companies still will need to drill if they want to keep their leases and avoid paying for them all over again.”[13]

Natural resources are not footloose: where the resource is rich, the extraction company will drill or mine. Studies of the oil and gas industry over the past 40 years make clear that state tax rates have miniscule impact on oil and gas production. A University of Wyoming study found that a 2 percentage point reduction in the state’s oil severance tax would increase production by only 0.7 percent over 60 years while dramatically decreasing government revenue. However, the study also found that raising taxes had a negligible effect on production, and that “the main effects of the tax increase would be to dramatically increase Wyoming’s severance tax revenues and to reduce federal corporate income taxes paid by producers.”[14] A study in Utah found similar results; that even significant changes to severance tax rates had large impacts on government revenue, but very little effect on industry production.[15] A Penn State study found that every $100 million in severance tax imposed on oil and natural gas companies would create a “net gain” of more than 1,100 jobs and would slightly boost gross state product. The study found this was largely because the negative effects of the imposed severance tax on employment, output, and income did not offset the increased spending of severance tax revenue by state and local government.[16]

A proposal to strengthen the severance tax is needed in Ohio and the administration is right to offer one. However the Kasich administration’s proposal is too low, too complex, contains big tax loopholes, and plans to spend the revenue raised on an income tax cut that will mostly flow to the wealthiest. Figure 2 compares revenues that could be raised under the Kasich proposal, at 5 percent (without tax breaks) and at 7.5 percent (without tax breaks).[17]

Although the Kasich plan has flaws, it is a step in the right direction. Unfortunately, the legislature has refused to consider the proposal. At a time that local governments and schools have just spent down their reserves and face a new and deeper round of cuts in the second year of the two-year state budget, legislators should be working to bring relief and restore jobs to communities.

Proposed uses of funds

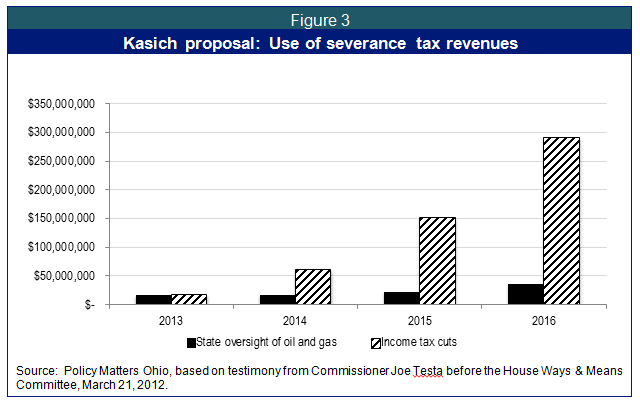

Under the Administration proposal, severance tax revenue from horizontal wells will be held in a new fund, the Horizontal Well Tax Fund. Revenues equaling what would be collected at current severance tax rates (3 cents per mcf of dry gas and 20 cents per barrel of oil) would be used for the regulation, oversight, and management of oil and gas resources and extraction by the Ohio Department of Natural resources. Extra revenue would be used for income tax cuts. (Figure 3.)

If those income tax cuts were implemented, Ohio households in the middle quintile – around the median income – would see on average a yearly benefit of $42 in years that the income tax give-back fund is $500 million. In years that it is smaller, they would see less. Households in the top 1 percent – those making more than $321,000 per year – would see $2,300 on average as a result of the proposed income tax cut in years when the severance tax raises $500 million. This is 55 times what a household in the middle-income quintile would receive.[18] The state already has a mechanism under which income taxes are reduced if the rainy day fund is fully funded.[19] There is little reason to set out an additional mechanism to cut income taxes, particularly when the state is underfunding key services and remains a long way from having an adequate financial reserve.

Funding local services in impacted communities

Our 2011 report, Beyond the Boom: Ensuring Adequate Payment for Mineral Wealth Extraction, recommended that severance tax proceeds be used to deal with high local costs associated with drilling. Kasich’s proposal adds a refundable $25,000 fee per well for local impact, calibrated to expenses related to roads, and it adds natural gas liquids to valuation of mineral reserves for property tax purposes. Property tax collections from mineral reserves has a significant lag, as a well must be drilled and production must commence and be evaluated before reserves are added to the property tax rolls; in addition, property tax collections lag by a year. By the time the local property tax collections are rising, the local impact fee must be paid back to the well owner.

Fracking will impose new costs on communities. Horizontal drilling has unusual costs that recur as the well is stimulated over and over: swarms of workers, truckloads of supplies, well preparation, wastewater disposal or recycling. Moreover, oil wells in shale generate an initial rush of oil that declines quickly, meaning more wells need to be drilled to produce oil from shale compared to conventional sources. The “treadmill” of drilling and fracking activity means heightened and more continuous industrial impacts on rural infrastructure and stress on community services.[20] Major energy states use the severance tax to provide local resources to help with the impact of drilling. Colorado provides 63 percent of the severance tax to local government. Montana provides 39 percent; North Dakota, 11 percent; Wyoming, 35 percent.[21]

Other states have found it necessary to provide resources to impacted communities because the drilling has caused local costs that go beyond road upgrading and repair. The Pennsylvania Cooperative Extension program looked at communities impacted by drilling in the Marcellus Shale and found 43 percent of communities reported an increase in population and 39 percent saw higher school enrollment; 30 percent saw a rise in use of emergency services. Conflict was up in some places (21 percent); crime rose in some (17 percent). Environmental issues around problems in water quality (17 percent) and air quality (13 percent) and other issues (17 percent) were reported.[22] Road maintenance increased for 65 percent of responding communities.

There is no room in Kasich’s local impact fee proposal to address the repeated treadmill of well stimulation. Given the ongoing impact associated with horizontal wells, and impacts that go beyond roads, different solutions need to be considered. A non-refundable up-front fee, combined with additional support from the severance tax itself, should be part of the solution for Ohio.

A permanent fund

Revenues from an adequate severance tax should be used to restore state services and to provide for impacted communities, but it should also provide for some very specific, long-term needs:

- To underwrite long-term planning for a diversified economy in impacted communities and regions after the minerals are depleted, and;

- To provide a cushion for risk management, in the case of sudden and unexpected liability in water contamination, poisoning of soil, animals, and land.

Seven of the nation’s largest energy states use a financing tool referred to as a permanent fund to address this kind of financing expense. The state should use severance tax revenues to establish a permanent fund for these purposes and use combined earnings and ongoing revenues to address redevelopment and other specific needs emerging from or after the drilling or mining.

Summary

The Kasich administration proposal to increase the severance tax is a step in the right direction, but the proposed rates are too low, the structure is too complex, and there are too many tax breaks that erode collections. The proposed use: for income tax cuts – ignores the pressing needs of the state, local communities and places impacted by drilling.

The industry will drill where the resources lie. The huge volume of land leases already signed indicates the resource is here. It is the responsibility of elected leadership to strike the best deal that they can, and to use the funds as severance taxes are used around the nation: To boost the economy, create jobs, help impacted communities and build a brighter future for all Ohioans.

Recommendations

- The tax rate on all oil and gas needs to be higher than 4 percent. A 5 percent severance tax rate should restore local jobs, schools and services and help impacted communities. An additional 2.5 percent should be used to create a permanent fund – structured like the severance tax but dedicated to economic recovery from the drilling and to fully fund a comprehensive risk management strategy.

- There should be no tax breaks. Tax breaks for cost recovery were first used as horizontal drilling and pressurized extraction were under development. Other states have such breaks, but they reflect years of legislative fights that oil company lobbyists won. There is no reason to adopt the outcomes of those battles in a new tax structure in Ohio.

- All production from the well - dry gas, wet gas and oil - should be taxed at the same rate.

- Funds should not be used for tax cuts at a time when spending cuts have led to over crowded classrooms, lost jobs, higher university tuition, and sharp cuts to health and human services - like the pending $6.2 million cut to drug and alcohol addiction services.

- Revenues should be reinvested to restore local jobs and services, fostering economic recovery and investing in the future.

- Revenues should be allocated to support local communities with up-front costs of drilling and to build a diversified economy for after the drilling is done.

- Revenues should fund a permanent fund to prepare for the future and to finance a robust risk management strategy.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Tim Krueger, research assistant, for double-checking the numbers in this report, and to Zach Schiller, research director, for his comments and suggestions. As always, any errors are the sole responsibility of the author.

[1] Policy Matters Ohio, “Income Tax Cut Would Favor the Affluent: Middle Class Ohioans Wouldn’t Get enough for a Tank of Gas,” March 19, 2012, available at http://www.policymattersohio.org/tax-cut-impact-march2012.

[2] Estimates are based on production projections of the Ohio Department of Taxation; see Appendix A.

[3] Policy Matters Ohio, “Beyond the Boom,” December 2011.

[4] Dry gas is called ‘pipeline quality gas’ in the legislative language stripped out of HB 487. The bill did not define "pipeline quality gas," but the Ohio Legislative Services Commission clarifies that this term is used in the natural gas industry to refer to "dry" gas (i.e., primarily methane) after purification or processing to remove condensates, other "wet gas" components and water or other impurities to a degree that the pipeline companies will allow the gas into their main transmission pipelines.

[5] From the administration’s website at www.governor.ohio.gov/Portals/0/pdf/MBR/FINAL%20Income%20Tax.pdf.

[6] Testimony of Tax Commissioner Joe Testa before the House Ways & Means Committee, March 21, 2012.

[7] Estimates based on simulation model of the Ohio Department of Taxation.

[8] For example, the Public Child Services Association of Ohio has suggested a $20 million fund could encourage counties without a levy to raise local resources to protect and serve children in need. The Ohio Association of County Boards Serving People with Developmental Disabilities suggests an $8 million investment by the state could draw down matching federal funds and create a fund of $21 million to address the waiting list of 14,000 Ohio families waiting for assistance. Small sums of tax revenue could restore services to help many Ohio families in need of specialized services.

[9] E-mail from the Ohio Department of Taxation Public Information Office, April 25, 2012.

[10] Headwater Economics and Stanford University, “Benefitting from Unconventional Oil,” April 2012; see also production projections per well in Appendix A.

[11] Assuming 24 months of tax breaks at the low scenario market prices; see Table 2 and Appendix A.

[12] While cautioning against an increase in spending, he addressed a failed attempt by Democrats to get an amendment for $400 million for schools and additional funds for local governments. Gov. Kasich said he couldn't "conceptualize or even imagine" why anyone would pursue such a measure after the state just dug itself "out of an $8 billion hole." Gongwer Ohio, Volume #81, Report #81, Article #6--Thursday, April 26, 2012

[13] Dan Shingler, “Even with higher taxes, drillers will drill,” Crain’s Cleveland business, March 26, 2012.

[14] Shelby Gerking, et al, “Mineral Tax Incentives, Mineral Production and the Wyoming Economy,” December 2000.

[15] Gabriel Lozada and Michael Hogue, “The Effect of Proposed 2009 Tax Changes on Utah’s Oil and Gas Industry,” University of Utah, December 18, 2008.

[16] Rose M. Baker and David L. Passmore, “Benchmarks for Assessing the Potential Impact of a Natural Gas Severance Tax on the Pennsylvania Economy,” Penn State Institute for Research in Training & Development, September 2010.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Policy Matters Ohio, “Income Tax Cut Would Favor the Affluent: Middle Class Ohioans Wouldn’t Get enough for a Tank of Gas,” March 19, 2012.

[19] Ohio Revised Code Sections 131.44 and 5747.02

[20] Headwater Economics and Stanford University, “Benefitting from Unconventional Oil,” April 2012.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Marcellus Shale Education and Training Center (MSETC), “Natural Gas Drilling Effects on Municipal Governments in the Marcellus Shale Region (Part IV) Local Government Survey Results from Clinton and Lycoming Counties,” http://bit.ly/IUfugT, accessed 12/07/2011.

Tags

2012FrackingRevenue & BudgetWendy PattonPhoto Gallery

1 of 22