Testimony: Tax cuts, flat tax aren't the answer

September 26, 2016

Testimony: Tax cuts, flat tax aren't the answer

September 26, 2016

Contact: Zach Schiller, 216.361.9801

Chairmen Peterson and Schaffer and members of the committee: My name is Zach Schiller and I am research director at Policy Matters Ohio, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization with the mission of creating a more prosperous, equitable, sustainable and inclusive Ohio. Thank you for the opportunity to testify today.Ohio needs a tax system that will generate adequate revenue to make the investments we need for our state to thrive. Ohio has important needs that are not being met, while critical indices of community well-being lag: A recent public health assessment noted that several national scorecards place Ohio in the bottom quartile of states for health, and the state’s performance on population health outcomes has steadily declined relative to other states over the past few decades. College education is even more unaffordable, and student debt higher, than the unenviable national averages. Pre-K enrollment of low-income children lags far behind the national average, and Ohio is also among the hardest of states in which to get childcare aid. Public transit service is being cut in Cleveland, and fares raised, even as hundreds of millions of dollars are needed statewide to replace existing equipment and meet future needs, according to a state transportation department study.

Yet state policy has been directed at reducing taxes, despite these needs. Since 2005, the General Assembly has cut the state income tax rates by a third, created a huge new income-tax exemption for business income, eliminated our corporate profits tax, repealed a major local business property tax on machinery, equipment and inventory and jettisoned the estate tax. To pay for part of this, it has increased the sales tax, boosted the cigarette tax, and created a new business tax on gross receipts, the Commercial Activity Tax. The advent of casinos and racinos also has led to taxes on those activities. But the net is a reduction in revenue of more than $3 billion a year.

Advocates of these tax cuts have argued that they are needed to boost the economy. But if that was the theory, it has not worked out that way. We have more than a decade of experience, and can look at how Ohio has done. If the tax cuts were as crucial as they were supposed to be, one would think by now we should have seen positive results. But our job and household income growth have lagged behind the nation. More on this later.

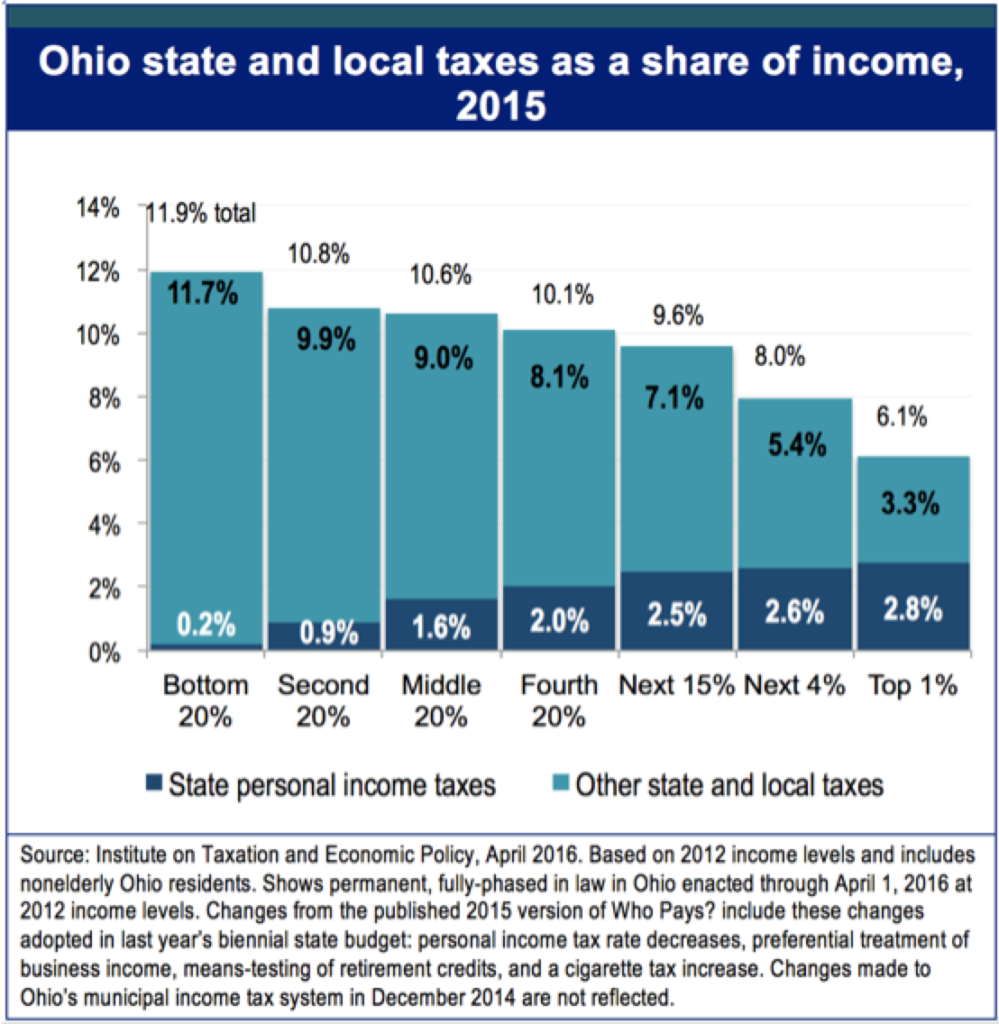

Who has benefited from the tax cuts? Primarily, they have gone to affluent Ohioans. Overall, the top 1 percent, who made more than $360,000 a year in 2014, received an average annual tax cut of $20,000 from the major tax changes between 2005 and 2014 (that doesn’t include last year’s cuts). On average, Ohioans in the bottom 60 percent of the income spectrum (making $54,000 or less) are paying slightly more. These numbers came from an analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, a national research group with a sophisticated model of state and local tax systems. This added to the tilt of Ohio’s state and local tax system in favor of the wealthy, shown in Table 1 below:

Table 1.

As Table 1 illustrates, the bottom fifth of Ohioans is paying almost twice as much of their income in state and local taxes as those in the top 1 percent do. Middle-income Ohioans also pay more of their income in state and local taxes, 10.6 percent, than the top 1 percent (the income groups in Table 1 are slightly different than those cited previously on the impact of the 2005-2014 tax changes because it is based on incomes from 2012). Much of the tax shift results from the reduction of the income tax and its partial replacement with sales- and cigarette-tax revenues. These fall more heavily on lower- and middle-income residents. Ohio’s tax system is adding to inequality.

A study earlier this year found that most of the richest people in the country choose where to live based on something other than tax rates. This research severely undercuts claims that the income tax causes the richest residents to flee to states with lower tax rates. Researchers at Stanford University and the U.S. Treasury Department examined all tax returns for million-dollar income-earners across the country over 13 years – 45 million tax records in all – and found that such tax flight occurs, “but only at the margins of statistical and socioeconomic significance.” The authors concluded that, “The most striking finding of this research is how little elites seem willing to move to exploit tax advantages across state lines in the United States.” I strongly urge that you read this study, which debunks a key rationale for the income-tax cuts Ohio has approved.

Nor are many of the most highly valued private companies flocking to low income-tax states. Policy Matters Ohio recently looked at where some of the highest-profile start-up companies are located, to see if state income taxes played a role. Such companies as Uber, Airbnb, Snapchat and Pinterest, dubbed “unicorns” by Wall Street, have been valued by their investors at $1 billion or more.

We found that by far the largest number of these companies – a whopping 55 of the 87 U.S.-based firms on a list compiled by the Wall Street Journal in April – are located in California. That state has by far the highest top income-tax rate in the country, at 13.3 percent. Another 10 are in New York State, whose top rate of 8.82 percent ranks 6th highest in the nation. A paltry five unicorns are based in states without income taxes (Florida, Washington and Texas).

Clearly, income taxes aren’t an impediment to these high flyers. Some of these firms will never meet their investors’ high expectations and will instead fizzle out. The valuations mark just one point in time; already, some of them have run into trouble. And of course, a lot more goes into regional economic success than where these high-profile businesses happen to establish themselves.

However, like the recent study on millionaires, their locations are one more sign that arguments for lower income taxes may sound simple and convincing, but have little basis in fact. For a variety of reasons, cutting taxes is no prescription for economic vitality. While this might surprise some, it’s really not that surprising. Companies can only thrive where there are well-trained workers, good transportation, and strong markets. Those require public investment in schools, infrastructure, worker training and services.

Overall, Ohio’s taxes are not high. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau reported on the state taxation department web site for Fiscal Year 2013 (see http://www.tax.ohio.gov/Portals/0/tax_analysis/tax_data_series/state_and_local_tax_comparison/tc12/TC12CY13.pdf), the most recent available, show that per person, our state and local taxes amount to $4,275, slightly less than the national average of $4,604. As a share of personal income, Ohio state and local taxes are 10.6 percent of personal income, virtually the same as the 10.5 percent nationally.

Policy Matters Ohio testified previously on tax expenditures, so I will not go over that in detail here (see our earlier testimony: http://www.policymattersohio.org/taxbreak-testimony-march2016). Since then, the Senate has passed its own version of House Bill 9, the bill sponsored by Rep. Terry Boose that would set up a permanent committee to review tax expenditures. We hope that this commission will help ensure that House Bill 9 is approved this year, in line with your mission to review the state’s tax structure and tax credits in particular. In addition, the committee should recommend that in next year’s biennial budget, funding be included for the Legislative Service Commission to do a thorough study of each tax expenditure prior to its examination by the review committee.

We should learn from the Kansas experience. It has experienced poor economic growth and persistent budget problems since its legislature slashed income taxes, something Gov. Sam Brownback said at the time would be “like a shot of adrenaline into the heart of the Kansas economy.” In July, Standard & Poor’s downgraded Kansas’s credit rating for the second time in two years, from AA from AA-, leaving Kansas below 41 other states.

Moving to a flat-rate income tax would be ill advised. As you have seen, Ohio already slants its tax system against low- and middle-income residents, and a flat-rate tax is likely to further increase that. Under a 3.5 percent or 3.75 percent flat tax, most Ohioans would pay more so that a tiny share could pay less. Our graduated tax system means that a flat tax is likely to have that effect. This explains why Tax Commissioner Testa earlier told you that, “It’s going to be hard to come up with a rate that doesn’t create a lot of losers.”

Even aside from the higher taxes that a flat rate is likely to mean for most Ohioans, there are other reasons why such a move is not sensible.

- It won’t do anything for small business – you already have cut the income tax to zero for the first $250,000 in business income, and set a 3 percent rate on income above that amount.

- It has no direct connection to state economic performance. Among the seven states that have had a flat-rate tax for the past decade, three have shown better job growth than the nation as a whole. But four have lagged behind – and those four happen to be the ones most similar to Ohio: Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

- It won’t simplify the tax system; the number of brackets does not matter when most taxpayers can simply find their rate in a table, whichever bracket they happen to be in. Simplifying the system can be done by cutting unnecessary tax expenditures, but that has nothing to do with a flat tax.

- It could hurt the state’s ability to finance services going forward. Over time, the income tax more closely tracks the growth in the economy than the sales tax, which covers a smaller share of purchases with each passing year. Ohio should rely on a diverse set of revenue sources to provide adequate funds for needed services and growth in revenue over time.

In fact, the income tax should be stronger, not weaker. Besides making the tax system fairer, that would add to the state’s financial resources. It would allow for needed capital investments and make it easier for the state to stay within the 5 percent debt limit. Ohioans also are assured by a constitutional provision that at least half of the income tax that is collected from within their school district or local government will return there

Ohio needs to modernize its tax system so that it covers today’s – and tomorrow’s – economy, not yesterday’s.

As the service sector grows and online purchases proliferate across a growing swath of the economy, the tax system needs to cover those sectors. Otherwise, they receive an implicit subsidy – be it software that is sold online compared to in a store or an Airbnb booking compared to a hotel room. While we have taken some steps in that direction, such as the provision in the 2013 budget bill extending the sales tax to digital goods and services such as Netflix, I-Tunes and e-books, we have not done nearly enough to adapt our tax system.

Ohio should ensure that our tax system is appropriately updated to respond to what some have called the gig economy. Our sales tax already is supposed to cover Uber, Lyft and other transportation network companies, though it remains unclear to the public if these entities are all collecting it. Airbnb has voluntarily agreed to collect local lodging tax in Cuyahoga County, and Cleveland approved an ordinance under which the company is collecting the city’s 3 percent bed tax. But state law needs to be revised so that state sales tax is required on these bookings when the establishment has less than five rooms. In addition, the online booking agent should be responsible for remitting the tax, and the tax should cover its fees along with the cost of the rooms themselves. Localities should be permitted to levy their own taxes on these entities, just as they are with hotels.

As you know, the federal government has told Ohio that we need to adjust our sales tax on managed care organizations to meet U.S. requirements. Besides the need to address the state’s own finances, the tax also provides close to $200 million a year to counties and transit agencies. The state needs to find a fix that protects health care but also local public finances.

Modernizing our tax system also means overhauling the severance tax so that it captures more than the current tiny share of revenue from hydraulic fracturing. Studies of the oil and gas industry over the past 40 years make clear that state tax rates have miniscule impact on oil and gas production. The state of Ohio needs to join other major producing states with a severance tax that covers the external costs of production imposed on roads, bridges, public health, housing and other civic functions of local government, and builds a stronger economy for when the natural resources are depleted. We recommend a 5 percent severance tax on the value of oil and gas, with an additional 2.5 percent during periods of high production and high prices, to be put aside in a permanent fund for economic development, education and other long-term investments.

Bringing our tax system up to date also means collecting the use tax due on catalog and Internet purchases. This is not a new tax; the use tax has been in place since the 1930s. Enforcing existing law is not a tax increase. As you probably know, a number of states have passed legislation attempting to see that more of this tax is collected, or challenging the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1992 Quill decision that prohibits states from imposing sales and use collection obligations on businesses without an in-state physical presence.

Ohio may want to consider enacting a law like that in Colorado that requires companies to notify customers that they may owe use tax and report annually to state tax authorities on purchases made by individual customers. It also calls for providing an annual report to each customer compiling their total purchase information, along with a statement that the total purchase information (but not the item breakdown) has been provided to their state’s revenue department and that they may owe use tax on their purchases. This law, a form of which also was recently enacted by Louisiana, has been upheld by the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals. Regulations in Colorado exempt businesses with less than $100,000 in annual sales in the state, and the annual report to customers is only required if the buyer bought more than $500 in the preceding year. The law also provides that no information about the nature of the purchases is to be provided to the revenue department, just the dollar amount. Such a law would not be a complete answer, but would make a good interim step while we wait for action by Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court.

Separate from the collection of taxes already due, the shrinking share of Ohio’s economy that is covered by the sales tax mandates a long-term evaluation of adding services to the sales-tax base

Some services clearly should be added. These include lobbying and debt collection, both of which Gov. Taft unsuccessfully attempted in 2003. In particular, we should evaluate consumer services and add to those that are covered by the tax.

We should not move in the opposite direction and remove the sales tax from temporary employment services. This would encourage companies to hire temporary workers instead of creating regular employment with stability. It would work against legislative efforts to reduce reliance on public assistance, as a number of temporary staffing firms rank among those with the most employees receiving nutrition aid. It would weaken the state’s tax base and reduce revenues for local governments and transit agencies.

While Ohio needs to broaden its sales tax to capture a greater share of purchases, that will affect low- and moderate-income residents more than others, as they would pay the most as a share of income. In order to offset this, the General Assembly should consider the adoption of a sales tax credit, in use in a number of other states. These credits provide a set amount for each family member to offset some of the cost of a sales or similar tax. See our 2013 report: http://www.policymattersohio.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/SalesTaxCreditES_Apr2013.pdf

At the same time, we need to expand our state Earned Income Tax Credit. The General Assembly took positive steps over the past three years in creating a state EITC and raising it to 10 percent of the federal credit. The federal EITC alone helped 177,000 working Ohioans, including 93,000 children, stay out of poverty each year from 2011-2013, and it eased poverty for many more. However, the state EITC could be a much more powerful tool for helping working families make ends meet and provide for their children. Because of limits imposed on its value, just a tiny share of the poorest workers see any benefit from the credit and the benefit is modest. Unlike the federal credit, Ohio’s EITC cannot exceed what a taxpayer owes in income taxes, and for a taxpayer with income over $20,000, it cannot exceed more than half of what he or she owes in income taxes. That means that it does nothing to reduce the substantial share of income these same taxpayers pay in sales taxes and property taxes. If the General Assembly removed these limitations, the state EITC would reach far more of the workers who need it most and be a better-targeted income support.

Over the generation between the late 1970s and the first decade of the new century, the share of Ohio state and local taxes paid by business declined while that of individuals increased. Then, in 2005, the General Assembly approved the phase-out of two major business taxes – the corporate franchise tax on nonfinancial companies and the tangible personal property tax – and their replacement with the new Commercial Activity Tax. One clear result was a significant reduction in business taxes. Even in the bad recession year of 2009, the old corporate franchise tax would have generated nearly $1.4 billion, and nationally, state corporate income taxes have increased since then. The tangible personal property tax regularly generated at least $1.6 billion. Based on CAT revenue in fiscal year 2014, the net loss in annual revenue is in the neighborhood of $1.5 billion. As the Ohio Business Roundtable told the Ohio Supreme Court in a 2008 filing: “The new business tax system substantially lowered the overall tax burden on business.” These cuts are still reverberating through local governments, and reducing the amounts that levies across the state bring in for everything from children’s services to community colleges.

More recently, owners of S Corporations, limited liability companies, partnerships and other business entities who are taxed on their profits through the personal income tax received a break on that tax. Altogether, this is likely to become the second-largest tax expenditure of any the state tracks, amounting to as much as $800 million a year. Business owners in general hire or expand when there is a growing market for their products or services, not because they have more cash in their wallets from lowered taxes. There was little reason to think this big new tax break would accomplish much in the way of boosting the economy – and indeed, the overall results have been weak. Since it was approved in 2013, the tax break has not produced overall job gains for the state or a significant increase in employment at small businesses that were hiring for the first time. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, such small Ohio businesses in 2015 were hiring fewer new employees than comparable small companies were a decade earlier, when major cuts in income-tax cuts were enacted.

To be clear: No one is suggesting that we should reinstate the tangible personal property tax. However, Ohio is one of only six states without a corporate income tax. We should restore a solid corporate income tax, so that companies pay taxes on their profits, and integrate it with the CAT, so that we make up some of the revenue lost with the 2005 business tax changes.

We have more than a decade of experience with income and business tax cuts. Ohio job growth has underperformed the national average since the big 2005 tax cuts were approved (1.6% vs. 7.9%), since January 2011 (8.6% vs. 10.5%), and over the past 12 months (1.4% to 1.7%). At the same time, previous increases in the income tax did not lead to job losses. The 7.5 percent top income-tax rate adopted under Gov. George Voinovich in 1992 did not prevent Ohio from generating more than 100,000 jobs each year from 1993 to 1995. We have not managed that any time in recent years, while cutting top income-tax rates. The evidence is clear: Tax cuts are not the answer.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify. I would be happy to answer any of your questions.

###

Policy Matters Ohio is a nonprofit, non-partisan research institute

with offices in Cleveland and Columbus.

Tags

2016Ohio Income TaxRevenue & BudgetTax ExpendituresTax PolicyZach SchillerPhoto Gallery

1 of 22