Testimony to the Senate Ways & Means Committee on HB 64

May 06, 2015

Testimony to the Senate Ways & Means Committee on HB 64

May 06, 2015

Contact: Zach Schiller, 216.361.9801

By Zach Schiller

Good morning, Chairman Peterson, Ranking Member Tavares and members of the committee. My name is Zach Schiller and I am research director at Policy Matters Ohio, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization with the mission of creating a more prosperous, equitable, sustainable and inclusive Ohio. Thank you for the opportunity to testify today regarding the tax provisions of House Bill 64.Ohio needs more tax revenue, not less. We need to restore aid to local governments. We need to help more of our young people afford college. We need to tear down or rehabilitate the tens of thousands of abandoned houses that resulted from the foreclosure crisis. We need to help more families pay for childcare, so the parents can work. We languish near the bottom among states in public health indicators. Our support for public transit ranks below that of South Dakota and needs a substantial boost. These are just a few of our unmet needs.

While there are a number of positive elements in Gov. Kasich’s tax proposal, such as raising the severance tax and cutting some unnecessary tax breaks, further slashing income taxes is not in Ohio’s interest. It detracts from Ohio’s fiscal stability, and is unlikely to result in accelerated job creation. We have not seen greater job gains after previous Ohio income tax cuts and there is no reason to expect a different result this time. The House version of HB 64 makes this same mistake.

Income-tax cuts are a poor strategy for boosting our economy. Other factors are far more important in state economic growth, including investments in education. And most of the relevant academic literature finds that state income tax levels have little effect on economic growth. Just last week, a study by the researchers at the Tax Policy Center found that “neither tax revenues nor top income tax rates bear stable relations to economic growth or employment across states and over time.”

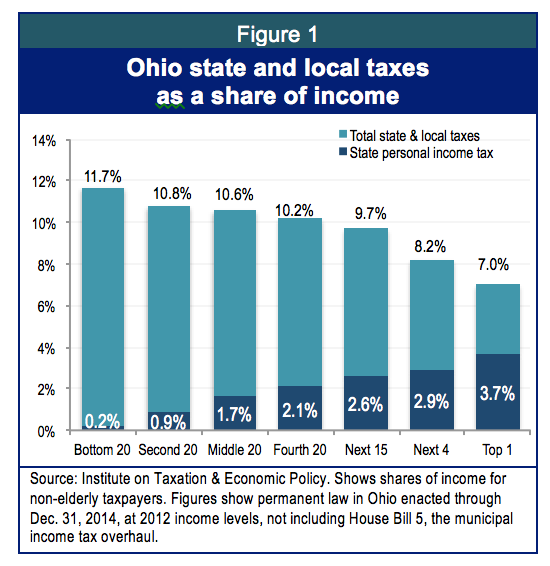

Our state and local tax system is weighted against low- and middle-income Ohioans. The chart below shows how much non-elderly tax filers in different income groups pay in such taxes as a share of their income. It also indicates how the personal income tax fits in. As you can see, the top 1 percent, who made at least $356,000 in 2012, pay just 7.0 percent of their income in state and local income, property, sales and excise taxes. By contrast, the lowest fifth, who make less than $18,000, on average pay 11.7 percent (a full description of the data is available at http://www.policymattersohio.org/tax-report-jan2015).

Ohio’s personal income tax is the one major tax that is based on ability to pay. You can see that cutting that tax will benefit low-income Ohioans very little. Reducing the income tax further will skew the tax system even more against lower- and middle-income Ohioans.

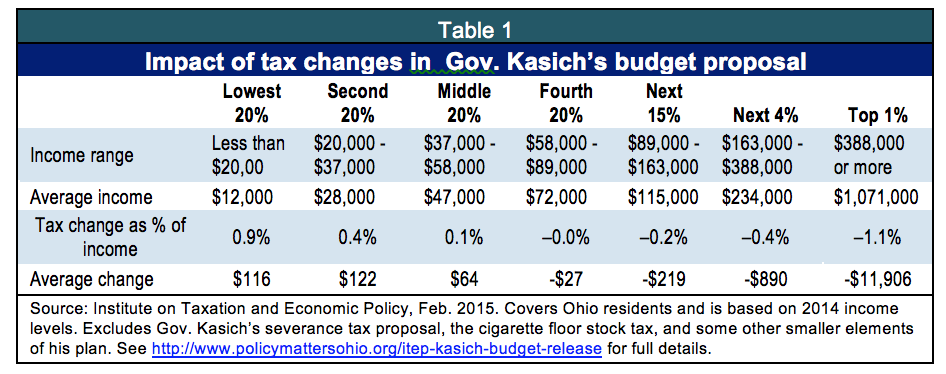

These data are based on an analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, a nonprofit research group in Washington, D.C., that has a model of the tax system. At our request, ITEP also examined Gov. Kasich’s tax proposal. Its review included all the biggest ongoing elements of the proposal except the severance tax. Please note that this analysis is not directly comparable to the one mentioned above because it is based on 2014 income levels and takes in all Ohio residents.

The bottom three-fifths of Ohioans would pay more as a group under the governor’s plan, as most of the increases like the sales-tax rate boost would fall more heavily on those with low or middle incomes. Even excluding the proposed increases in the cigarette and tobacco taxes, the proposal remains highly rewarding to Ohio’s most affluent, while costing more on average for the bottom two-fifths of Ohio residents.

The numbers shown represent the average change for people in each income group. Individual taxpayers may do better or worse. There is little doubt that many Ohioans will see income tax cuts under the governor’s proposal. However, fundamentally, this tax plan redistributes income from poor and middle-class Ohioans to the affluent. We should not embrace that policy.

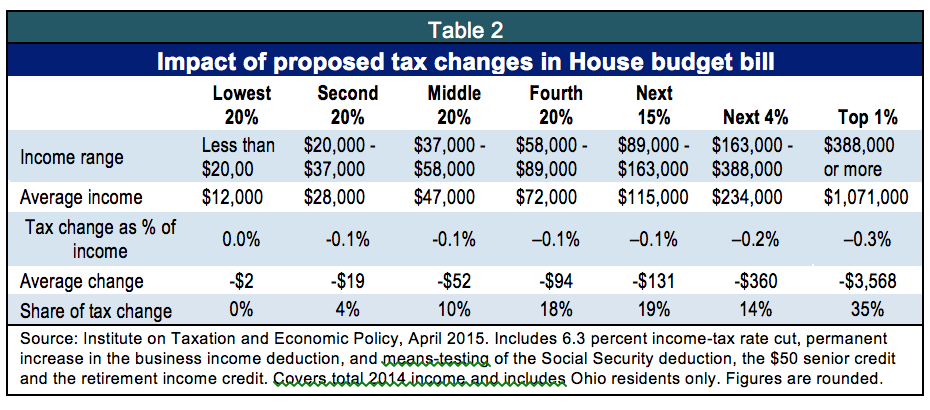

The institute also analyzed the House tax plan at our request. As you can see, it does not shift who pays taxes to lower- and middle-income Ohioans to the same degree as Gov. Kasich’s proposal would. However, it still would deliver thousands of dollars a year in tax cuts to the most affluent while providing so little to the poorest Ohioans it wouldn’t be enough for a gallon of milk. The average middle-income resident would get enough to buy a six-slice toaster oven at Bed Bath and Beyond.

As part of his testimony, Commissioner Testa provided examples of hypothetical taxpayers and how much they would pay in income and sales taxes in 2016 compared to 2011 (See Attachment G). These numbers, in part, reflect sales and income tax changes already enacted. After similar testimony in the House, the department provided information to House members reviewing the impact of the governor’s proposal for some of these same taxpayers. Unfortunately, even the latter information does not provide a full picture of how the governor’s proposal would affect taxpayers. It excludes a significant share of the tax increases that are a part of the proposal, such as the Commercial Activity Tax, the increase in local sales tax and other elements of the plan. This is why it paints a much rosier picture than the data presented in Table 1 above.

The governor’s proposed increases in the personal exemption would benefit a significant number of Ohioans, especially middle- and upper-middle-income taxpayers, who would receive most of that tax cut. But increasing the exemption does not make this a good tax plan for low-income Ohioans. One million Ohioans, or one in five tax filers, do not pay income tax. They will lose out under the plan—and many more will do the same. This is not because they don’t contribute; as a group, the poorest fifth of Ohioans pays more in taxes as a share of their income than others do.

Business income tax exemption

Creating an exemption for business income would be unwise for a number of reasons:

- It would be poorly targeted. Only a decided minority of businesses in Ohio whose income is reported through the personal income tax have employees. While data from the Taxation Department shows there are more than 1 million pass-through-entity businesses in Ohio, fewer than 300,000 private companies pay unemployment tax, which essentially means that they employ someone. If the goal is job creation, spreading a tax break to all businesses with receipts under $2 million is unlikely to succeed. Most of those who benefit will get too little in savings to add employees in any meaningful way. Business owners expand when they anticipate greater demand for their products or services, not because they have a few hundred dollars more in their wallets.

- Questions have been raised earlier about the possibility that this expanded tax break could lead to tax avoidance. Whether or not many companies try to take advantage of the $2 million threshold in Gov. Kasich’s proposal, there is a real possibility that some employees could become independent contractors, with no net gain to jobs or the economy.

- We have only just started seeing the results of the new business-income tax deduction established in 2013, which cost more than $300 million in its first year and quickly became the 9th biggest state tax break. So far, the results are not inspiring. New employment at small Ohio companies that hired employees for the first time fell between the first half of 2013 and the same period in 2014. Such new hiring remained 29 percent below the same period in 2005, when the last major income-tax cuts were approved. Overall jobs in the 21 months since the last budget passed have grown no faster than they did in the 21 months preceding that—in fact, the growth has been slightly slower. Why should we double down on this expensive strategy when we don’t have evidence that this new deduction works? That applies also to the House version of the bill, which would permanently increase the current deduction.

We support the structure of the severance tax on horizontal drilling outlined in the executive budget proposal. We have proposed a 5 percent severance tax on oil and gas alike, with an additional 2.5 percent dedicated to a permanent fund for investment in the people of Ohio and diversification of the economy on a long-term basis. The governor’s proposal is set at a similar, albeit slightly lower, level.

A severance tax should not be used to offset income tax cuts. It is by definition a tax that will be depleted as the resource is depleted. It rises and falls with the market. It is not stable. However, it is ideally suited for long-term investment, to mitigate impacts to the region and to help restore the last four years of cuts in aid to local governments.

In 2003, Gov. Taft attempted to apply the sales tax to lobbying, public relations and debt collection as Gov. Kasich is now. We support that effort (see, for instance, our 2008 report at http://www.policymattersohio.org/limiting-loopholes-a-dozen-tax-breaks-ohio-can-do-without). Lobbyists aren’t going to move to Harrisburg or Indianapolis because they have to start charging sales tax. Broadening the sales tax so it covers more of the economy, as the tax commissioner has shown, is a move in the right direction. We agree with Mr. Testa that the vendor discount is a windfall for some big retailers and should be scaled back.

But raising the sales tax rate is no formula for success. The average combined state and local sales tax rate if Gov. Kasich’s proposal is approved will be about 7.5 percent. State sales-tax revenues would be almost double those from the income tax in Fiscal Year 2017, and would make up more than half of General Revenue Fund tax revenues. This does not constitute balance.

While it has its ups and downs, the income tax grows with the economy over time. Sales-tax revenues don’t grow as fast, partly because the sales tax doesn’t cover some faster-growing industries. Are we going to need to raise the sales tax again to make up the difference? Or will this crimp our ability to support vital public services? Either way, this is not a swap that is likely to help Ohio’s finances. While the House version of HB 64 does not rely on sales-tax increases, it is based on more optimistic revenue projections than Gov. Kasich’s budget and the use of some one-time revenue.

A number of other tax measures that Gov. Kasich has proposed are worthy of consideration. As Commissioner Testa has said, raising the Commercial Activity Tax is appropriate, given the big tax cuts that Ohio businesses received earlier. Means-testing income-tax credits and deductions for seniors would make the tax system more fair—and represents smart policy in view of Ohio’s aging population. However, these and other measures to improve Ohio’s tax system should be considered on their own, not to pay for unneeded income tax rate cuts and the business-income tax exemption.

Earned Income Tax Credit

The General Assembly took positive steps over the past two years in creating a state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and raising it to 10 percent of the federal credit. The federal EITC alone helped 177,000 working Ohioans, including 93,000 children, stay out of poverty each year from 2011-2013, and it eased poverty for many more. However, the state EITC could be a much more powerful tool for helping working families make ends meet and provide for their children. Because of limits imposed on its value, just 7 percent of the poorest workers—those earning $19,000 or less—see any benefit from the credit and the benefit is modest. Unlike the federal credit, Ohio’s EITC cannot exceed what a taxpayer owes in income taxes, and for a taxpayer with income over $20,000, it cannot exceed more than half of what he or she owes in income taxes. That means that it does nothing to reduce the substantial share of income these same taxpayers pay in sales taxes and property taxes. If the General Assembly removed these limitations, the state EITC would reach far more of the workers who need it most and be a better-targeted income support.

At the same time, the both versions of the bill include other provisions that deserve closer scrutiny by the committee and the General Assembly. House Bill 64 would change the computation of recently awarded job creation and job retention tax credits so they would not be reduced as income-tax rates fall. It would also remove the cap on the job retention tax credit, so it would not be limited to 75 percent of the employer’s payroll. The House version goes further than the governor’s proposal and would allow companies to see their job creation and retention credits increased to make up for the effects of earlier tax cuts.

These proposed changes underline that a thorough review of tax expenditures is long overdue. There is no reason that $8.5 billion a year in tax exemptions, credits and deductions should be allowed to continue indefinitely, unlike regular spending, when their impact is the same as every spending line item you approve. While Gov. Kasich’s move to create a review committee is sensible, it should not be terminated after four years. Review of tax expenditures should be done regularly, not just once. In addition, exemptions, credits and deductions should be given sunsets, just as spending does not continue without authorization from the General Assembly.

Thank you for allowing me to testify. I am happy to answer any questions that you may have.

Policy Matters Ohio is a nonprofit, non-partisan research institute

with offices in Cleveland and Columbus.

Tags

2015Revenue & BudgetTax ExpendituresTax PolicyZach SchillerPhoto Gallery

1 of 22