Out-of-Step

August 26, 2014

Out-of-Step

August 26, 2014

Changes to the Ohio EITC this summer doubled the credit, but poor design choices mean that most low-income working families won't get the benefit.

Download Summary (2pp)Download full report (8pp)Press releaseChanges to the Ohio EITC this summer doubled the credit, but poor design choices mean that most low-income working families won't get the benefit.

More needed to make Ohio EITC a credit that counts

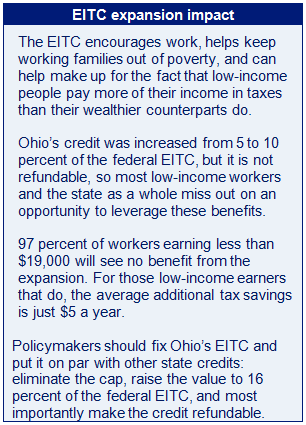

T he Ohio General Assembly recently expanded the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), doubling it from 5 to 10 percent of the federal credit. However, the credit remains out of step with nearly all other state EITCs, and the majority of Ohio’s poorest workers will see no benefit from the bump. Only 3 percent of tax filers earning less than $19,000 will see any tax savings from the expansion.[1] For the small number in this group that will benefit the average additional annual income tax savings is just $5.

he Ohio General Assembly recently expanded the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), doubling it from 5 to 10 percent of the federal credit. However, the credit remains out of step with nearly all other state EITCs, and the majority of Ohio’s poorest workers will see no benefit from the bump. Only 3 percent of tax filers earning less than $19,000 will see any tax savings from the expansion.[1] For the small number in this group that will benefit the average additional annual income tax savings is just $5.

The federal EITC is designed to accomplish three main purposes: It creates a strong incentive to work by making low-wage work pay; it provides additional income that helps low-wage working families keep their children out of poverty; and it helps make up for the fact that payroll taxes hit low-income families the hardest. The federal EITC meets these goals by refunding money to families and boosting household income.

State EITCs also help low-wage families make ends meet and provide for their children. Strong state credits can supplement the federal credit by offering an additional, modest income boost to those struggling to get by on low-wage work. State EITCs can also help make up for the fact that low-income people pay more of their income in state and local taxes than their wealthier counterparts do.[2] But for state credits to accomplish these goals and effectively leverage the benefits provided by the federal EITC, they must be well designed.

Nearly all state EITCs adopt the structure of the federal credit because the refundable federal credit works. The federal EITC is the most effective anti-poverty program in the nation, even though most people only claim the EITC for one or two years.[3] An estimated 191,000 Ohioans, including 99,000 children, were kept out of poverty by the federal EITC each year from 2010-2012.[4] Children in households that receive the EITC are born healthier, do better in school, have higher college attendance rates, and even earn more as adults, compared with low-income children whose families don’t get the credit.[5]

Ohio’s EITC is out of step. Ohio’s credit is nonrefundable, meaning the credit can only reduce tax liability. It is also capped, so that the maximum EITC that a filer with Ohio Taxable Income greater than $20,000 may receive is half of the tax that is due after certain exemptions.[6] Even with the recent expansion, it is below the average value of other state refundable credits (16 percent of the U.S. credit) and remains one of the weakest state EITCs in the nation.[7] The Ohio EITC reaches only a fraction of the poorest working families. It does little to bring about the fundamental policy goals of EITCs – to incentivize work, to keep families from falling into poverty, and to bring some balance to our tax code. In order for the Ohio credit to count for working Ohioans, we must address the design flaws: eliminate the cap and make the credit refundable.

Lopsided benefits of EITC expansion

Increasing the value of the Ohio EITC is a small step toward aligning our credit with the national average, but the credit remains inadequate. According to modeling done by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), a Washington, D.C. based research group with a sophisticated model of the tax system, simply expanding the Ohio EITC to 10 percent of the federal credit does very little for those claiming the EITC and nearly nothing for the poorest working Ohioans.[8] The expansion will have no impact on the tax bill of an estimated 97 percent of earners making less than $19,000 in 2013, who make up the poorest fifth of Ohio tax filers. For the 3 percent of this group that will see some impact from the change, their average additional tax savings is only $5 a year. In its current form, only 1 percent of the total tax credit expansion will go to the poorest working Ohioans.

The second and middle quintiles of earners receive the majority of the expansion’s benefits, with each quintile receiving 48 percent of the total tax change. Even so, the increased savings is slight. Only 11 percent of filers making between $19,000 and $34,000 will see any benefit from the expansion. Of those that see a tax change, the average additional savings is an estimated $60. The remaining 89 percent of those in this group will see no impact from the expansion.

Similarly, only 12 percent of the middle quintile, filers making between $34,000 and $54,000, will see any savings from the expansion. The average additional savings across that 12 percent will be about $55. The remaining 88 percent will not be affected. Overall, the additional tax savings for all filers in this income range averages to $6. Table 1 shows these results, in detail.

Poor policy design limits EITC impact

The Ohio Department of Taxation reports that through late July, 566,962 taxpayers claimed $67,495,715 in EITC in the credit’s inaugural tax year.[9] This is good news for Ohio in that many tax filers are aware of and claiming the credit. But these numbers do not reflect actual tax savings generated by the EITC. Many filers may have claimed the full EITC and been counted in the Department’s tally, but realized less actual EITC tax savings than they claimed due to the interaction between the EITC and certain other existing tax credits and exemptions. This gap between the amount claimed and the actual tax savings is created by the same design defect that prevents the expansion from targeting the poorest workers: lack of refundability.

Refundability is the most important design choice facing policymakers because it is the feature that makes the EITC a credit that counts for low-income working people. Refundability means that if the credit exceeds the income tax due, the extra is returned to the taxpayer as a tax refund. Ohio already has refundable tax credits on the books for motion picture producers, for historic building rehabilitators, and through the job creation and retention credits, for corporations and investors.[10]

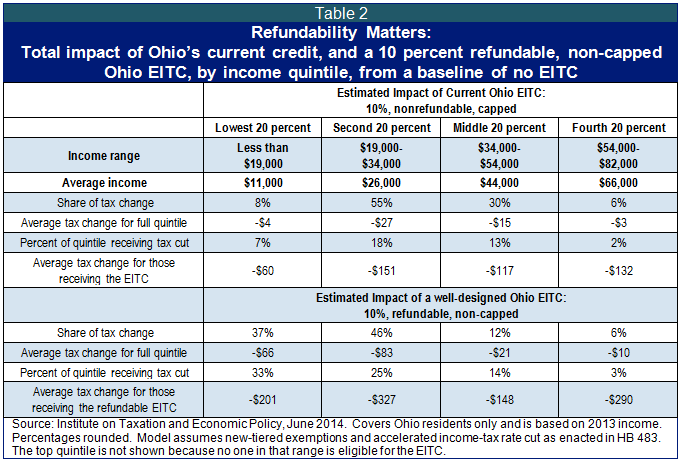

Table 2 demonstrates the total impact of our current 10 percent non-refundable, capped credit by quintile. In contrast to Table 1, which showed the changes resulting from expanding the EITC from 5 to 10 percent credit of the federal credit, Table 2 shows the total impact of both credits measured from a baseline of no EITC.[11] The table demonstrates how eliminating the cap and making the credit fully refundable would increase savings across all quintile groups, but more importantly drive savings to the lowest-earning workers.

Refundability would allow significant numbers of the lowest income earners to receive the EITC. Filers earning less than $19,000 would receive 37 percent of the overall tax change. A third of Ohio’s poorest workers would receive a tax cut. Among those that would receive a cut, the average tax change would be $201, nearly all of which would likely be returned to the family in the form of a tax refund. Under the current credit, including the impact of the expansion, only 7 percent of Ohioans making less than $19,000 will see any benefit from the EITC and for those that do, their average savings is about $60.

Nearly half of the tax cut generated from a 10 percent refundable credit would accrue to the second lowest group of earners. A quarter of filers earning between $19,000 and $34,000 would receive a tax cut and for those that do, their average annual cut would be $327, much of which would be returned to the families as a tax refund. Under the current credit only 18 percent will see some benefit, and for those that do, their average savings is $151.

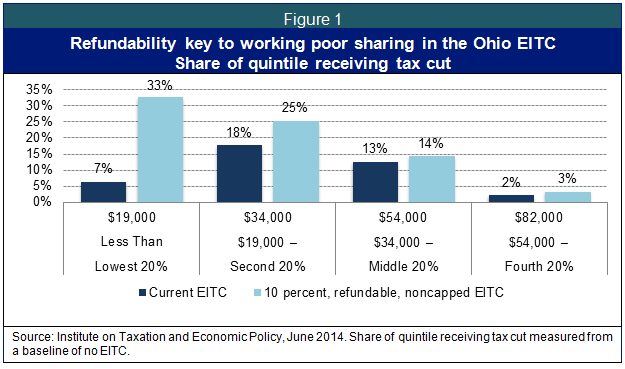

Figure 1 shows that a much larger share of poor workers would receive the Ohio EITC just by making the existing credit refundable and eliminating the cap. As is, the credit is too weak to reach more than a tiny fraction of Ohio’s working poor.

Refundability key to a functional EITC

The EITC has broader policy aims than just reducing or eliminating income tax liability. The credit is intended to encourage work and insulate low-wage working families from poverty. Ohio’s workers certainly need a boost. Far too many are working poor. About 44 percent of poor families in Ohio are also working families.[12] About 13 percent (291,495) of Ohio’s children are living in working poor households.[13] Nearly a quarter (24.7 percent) of all jobs in Ohio are in occupations with median annual pay that won’t keep a family of four above the poverty line.[14]

State EITCs serve as an additional boost to the federal credit, helping more families in need have a little extra income. Without refundability, the Ohio EITC is hamstrung in this respect. The credit will not target those most in need of the EITC as an additional work incentive and wage supplement. Ohio as a state will miss out on the potential boost for child achievement. Even relatively small increases in household income can have a big impact on child achievement. Research has shown that each $1,000 increase (in 2001 dollars) in annual family income while a child is between the ages of two and five improves school performance across a variety of measures, including test scores.[15]

The EITC is also intended to prevent very-low income workers from being taxed deeper into poverty. Low-income Ohioans pay more of their income in state and local taxes than affluent Ohioans do.[16] This is not because of the state income tax but because of sales, excise, and property taxes, which are regressive, meaning they fall more heavily on those of lower income. The poorest 20 percent of nonelderly Ohioans pay 0.3 percent of their income in personal income tax and another 11.3 percent in other state and local taxes.[17] The top 1 percent of Ohio income earners pay 4.4 percent of their income out as personal income tax and only 3.7 percent in other state and local taxes.[18]

The most recent round of tax cuts approved by the General Assembly primarily benefited the top income earners in the state and exacerbated this fundamental inequality.[19] This came on top of last year’s tax cuts which, according to a previous ITEP analysis, produced an average annual tax cut of more than $6,000 for the top 1 percent of Ohio earners, while the poorest 20 percent of earners saw an average tax increase of $12.[20]

The EITC is one of the most straightforward and effective ways to bring greater fairness to the tax code, but the state EITC can only be effective if the credit is refundable. Existing income-tax credits and exemptions already eliminate income tax liability for many. This makes the current nonrefundable EITC a redundant and ineffective credit for most of the lowest-income Ohioans.

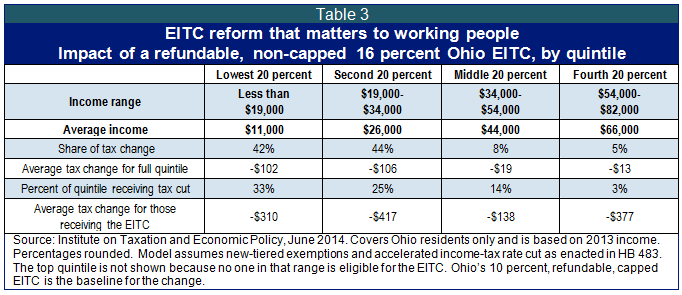

Meaningful reform, smart design

If Ohio were to bring our credit in line with the national average of states with their own EITCs, ours would be 16 percent of the federal EITC, refundable, and uncapped. As Table 3 shows, this would better serve the policy objectives of the EITC. The bulk of the expansion would be delivered to workers in the two lowest income quintiles. An additional 33 percent of earners in the bottom quintile would see some benefit from the reform.[21] The average tax refund among these recipients would increase by $310. A quarter of earners in the second income quintile would also see some benefit from the expansion. The average annual tax savings and potential tax refund for those receiving the credit would be an additional $417. This is a substantial boost to low-income budgets and would push back against the disparate treatment low-income earners receive under the Ohio tax code.

Design matters in terms of making the EITC a valuable credit for working people. Strengthening the credit, eliminating the cap and making the EITC refundable brings greater benefits to families across all eligible income quintiles. It is clear that a 16 percent refundable, non-capped credit would move more money down the income ladder, helping to offset a small portion of the recent tax shifts and allowing the state to better leverage the benefits of the federal EITC.

The EITC is designed to encourage work, help keep low-income working families out of poverty, and to make up for the fact that lower-income people pay a larger share of their income out in payroll taxes than do wealthier people. State EITCs are designed to supplement the federal credit and help maximize such benefits. While the Ohio EITC and the recent expansion provide some Ohioans with additional tax benefits, the amount is small and the poorest workers in the state receive nearly nothing. The Ohio credit can and should do more to leverage the benefits of the federal EITC. Policymakers should fix Ohio’s EITC by supporting a 16 percent, refundable credit, and eliminating the cap.

###

Policy Matters Ohio is a member of the Working Poor Families Project, a national initiative that advances state policies in the areas of education and skills training for adults, economic development, and income and work supports. WPFP supported this research on the EITC.

Appendix

[1] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy Microsimulation Tax Model, July 2014. ITEP’s modeling took into account the other income-tax changes the General Assembly approved simultaneously, including the accelerated phase-in of a 1 percent rate cut and higher personal exemptions for taxpayers making $80,000 or less. It is based on 2013 income estimates and covers Ohio residents only.

[2]See, Zach Schiller, “The Great Ohio Tax Shift,” Policy Matters Ohio, August 2014, available at http://www.policymattersohio.org/tax-shift-aug2014, accessed August 20, 2014.

[3] Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, and Arloc Sherman, “Earned Income Tax Credit Promotes Work, Encourages Children’s Success at School, Research Finds,” Center of Budget and Policy Priorities, April 15, 2014, available at www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3793, accessed May 20, 2014.

[4] The Brookings Institution, State Estimates of People and Children Lifted out of Poverty by EITC and CTC, per year, available at http://bit.ly/1gB4cSn, accessed July 8, 2014, based on Supplemental Poverty Measure Public Use Data, using three-year estimates due to sampling size.

[5] Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, and Arloc Sherman, supra at note 3.

[6]See, Hannah Halbert, “A Credit that Counts,” Policy Matters Ohio, October 2013, available at http://www.policymattersohio.org/eitc-oct2013, p.4, discussing the Ohio EITC cap.

[7] Ohio is one of 25 states that have an EITC. Only 3 other states have a completely non-refundable credit like Ohio. No other state uses a cap similar to Ohio, though some have tiered EITC amounts based on family structure or income, or partial refundability. See, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Rewarding Work through State Earned Income Tax Credits, April 2014, available at http://www.itepnet.org/pdf/pb15eitc.pdf.

[8]ITEP analyzed the impact of the income tax portions enacted in HB 483 elements and determined how these changes will impact the taxes of various income groups. The analysis uses 2013 income levels for the model. Model assumes new-tiered exemptions and accelerated tax rates as set out in HB 483. This analysis updates earlier analysis of the bill, Flawed Tax Cuts in Senate Budget Bill, May 2014, available at http://www.policymattersohio.org/senate-budget-may2014. Married, joint filers, with three or more dependents can qualify for the EITC if they earned up to $51,567 in tax year 2013. Earners in the fourth quintile have total income greater than the EITC eligibility threshold, yet the model suggests that some still qualify for the EITC. The number qualifying in this quintile is very small, but some unusual families do. For example, a family may have one worker earning $50,000 in earned income and a second person receiving $4,000 in non-earned income. The family could also have deductible expenses (health savings exemptions, moving expenses, student loan expenses) of $4,000. The total income ($54,000) pushes the family into the fourth quintile. But for both of the income tests used to determine eligibility for the EITC (Federal Adjusted Gross Income and earned income), this family’s income is only $50,000. The $4,000 in qualifying expenses reduces their AGI to $50,000, and some income such as unemployment compensation is not considered “earned income” for calculating the EITC. The family’s FAGI and Earned Income qualify for the EITC after these reductions.

[9] Gary Gudmundson, Communications Director, Ohio Department of Taxation, email to author data July 22, 2014. Numbers reflect claims made through July 22, 2014. While some returns are filed after the April 15 due date, it is likely that this sum reflects the bulk of those likely to claim the credit.

[10] Hannah Halbert, supra at note 6, p. 5. While it is not known how much of the total was paid in refunds, $68 million in the job creation tax credits alone were claimed against the Commercial Activity Tax in fiscal year 2013. Id.

[11]See Appendix A for a table that shows, similar to Table 1, the additional impact of changing our current 10 percent, nonrefundable, capped credit to a 10 percent refundable non-capped credit. It differs from Table 1, which shows the total impact of the credits measured from a baseline of no EITC.

[12] Working Poor Families Project, Population Reference Bureau, analysis of 2012 American Community Survey.

[13]Id.

[14] Working Poor Families Project, Population Reference Bureau, analysis of May 2012 Occupational Employment Statistics.

[15] Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, and Arloc Sherman supra note 3. Similarly, a credit that’s worth about $3,000 (in 2005 dollars) during a child’s early years may boost his or her achievement by the equivalent of about two extra months of schooling. Id.

[16] Policy Matters Ohio, “Ohio’s state and local taxes hit poor and middle class much harder than wealthy,” Jan. 30, 2013, at http://www.policymattersohio.org/income-tax-jan2013.

[17]See, Zach Schiller, “The Great Ohio Tax Shift: Changes since 2005 widen inequality,” p. 4, Policy Matters Ohio, August 2014, available at http://www.policymattersohio.org/tax-shift-aug2014, accessed August 20, 2014, using analysis from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 2013, based on Ohio tax law as of January 2013, tax covering nonelderly Ohio residents only at 2010 income levels. This analysis preceded tax changes enacted since January 2013.

[18]Id.

[19] Policy Matters Ohio, “Cuts and Breaks,” July 2014, available at http://www.policymattersohio.org/cuts-and-breaks-mbr-jul-2014.

[20]Patton, Wendy, Zach Schiller and Piet van Lier, “Overview: Ohio’s 2014-2015 Budget,” Policy Matters Ohio, Oct. 3, 2013, Table 1, p. 5, at www.policymattersohio.org/budget-oct2013. This analysis included the creation of the 5 percent nonrefundable EITC.

[21] This is a 3 percentage point increase over the benefit generated from just making the current credit refundable and removing the cap. That is, if Ohio made those changes and bumped its credit from 10 percent to 16 percent of the federal credit, an additional ten percent of bottom quintile earners would benefit. Compare Table 3 with Appendix A.

Tags

2014Hannah HalbertOhio Income TaxPhoto Gallery

1 of 22