Policy Matters Ohio defends crucial unemployment compensation benefits

December 01, 2016

Policy Matters Ohio defends crucial unemployment compensation benefits

December 01, 2016

Contact: Zach Schiller, 216.361.9801

Good morning Chairman Blessing, Ranking Member Clyde and members of the committee. My name is Zach Schiller and I am research director at Policy Matters Ohio, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization with the mission of creating a more prosperous, equitable, sustainable and inclusive Ohio.House Bill 620, while an improvement over its predecessor, House Bill 394, would significantly cut unemployment benefits for jobless workers. While some of the draconian measures in an earlier bill have been eliminated, these cuts would hurt tens of thousands of Ohioans each year when they are unemployed.

While we only received the fiscal note on the bill as this testimony was being completed, it reveals that unemployed workers – not employers – will pay the vast bulk of the improving the solvency of the unemployment trust fund. The analysis shows that between now and 2030, assuming one 1990s-style recession, the bill would cut benefits by more than $3.5 billion, or 19.5 percent. Employer taxes would increase by $716 million, or 4.4 percent. That means that unemployed workers would be paying for 83 percent of the cost of bolstering the fund. That is not an equitable share.

Specifically, HB 620 would reduce the maximum number of weeks of benefits from the current 26 to a sliding scale based on the monthly statewide unemployment rate. Claimants filing for benefits now, and all those who have filed since September 2014, would have seen a maximum number of 20 weeks of benefits had the bill been effect. This provision would have reduced benefits for nearly 70,000 Ohioans had it been in place last year. Cutting the maximum number of benefit weeks will weaken the positive role unemployment compensation (UC) plays in our labor market and economy, and the change is unlikely to generate significantly more employment.

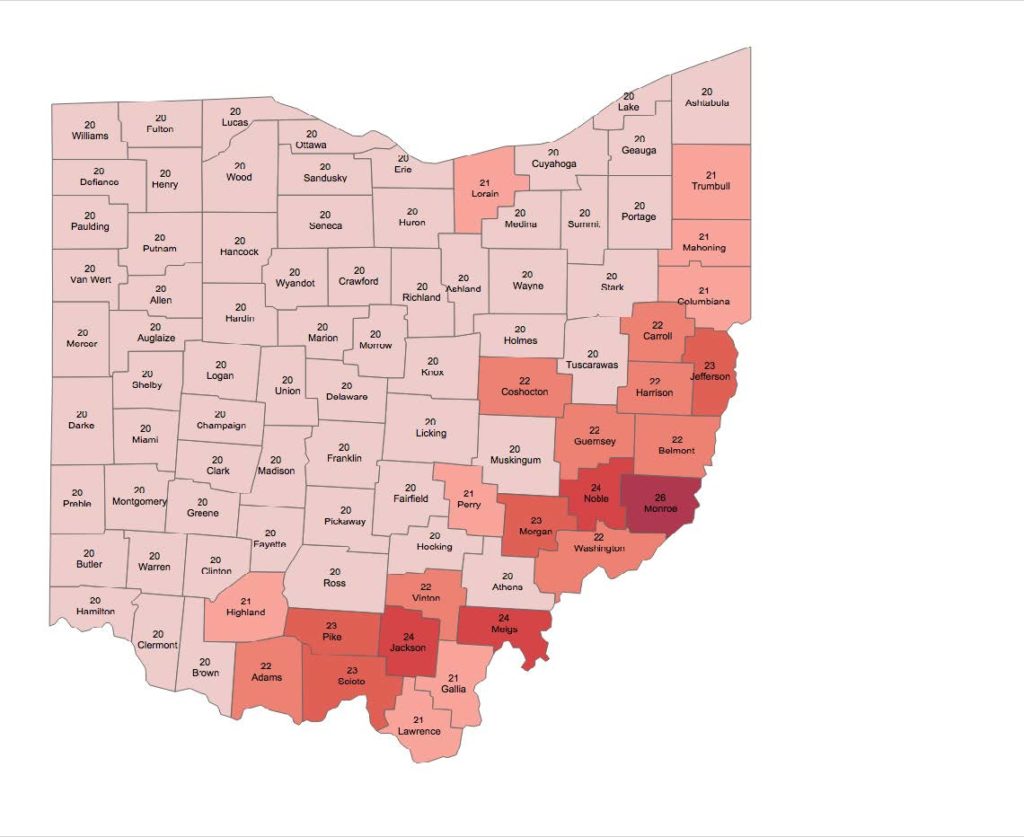

The bill also cuts benefits based on a statewide unemployment rate when rates in specific areas, both urban and rural, are well above that, and workers there cannot be expected to find jobs as easily as those where unemployment is lower. In Monroe County, the October unemployment rate was 9.1 percent, which under the sliding scale in the bill would produce 26 weeks of benefits. In Jackson, Meigs and Noble counties, unemployment rates of 7-plus percent would see the same 20 weeks as the rest of the state, though workers there would be eligible for 24 weeks if the state-wide scale were applied.

The map below illustrates how many weeks of benefits would be available in each Ohio county, based on October unemployment rates, if the sliding scale in the bill was applied using those local rates. You will note that this bill discriminates against Appalachian Ohio. While not shown on the map, it would have the same effect in cities where unemployment rates are higher.

This provision also is poorly drafted. It is unclear which unemployment rate is to be used – the seasonally adjusted rate? The statewide unemployment rate usually is released on the third Friday of each month. Does that mean that someone filing later that day, or on the following Monday, would see the number of weeks adjusted? It further says that if the rate is revised—and rates are subject to revision the following month – “the director shall use the higher rate to determine the individual’s maximum number of benefit weeks…” This appears to mean that the Department of Job & Family Services will retroactively increase the number of weeks for individual claimants, after they have begun receiving benefits. While we certainly favor the idea of claimants receiving closer to today’s standard of 26 weeks, this would be cumbersome to administer, to say the least. It suggests that the bill needs to be more carefully vetted.

Under HB 620, Ohio would no longer be among the 41 states that allow at least 26 weeks of benefits. Even among the handful of states that have imposed sliding-scale maximums linked to unemployment rates (only five have done so), none makes monthly adjustments in the maximum number of weeks.

The bill would replace the current dependency allowance system with another. While this would extend such benefits to all those with families, the amount is so small – no more than $8 a week – that it is not very meaningful. Pennsylvania’s payments, which this is modeled on, are at the low end among states that provide such benefits. During discussion of this issue, it’s often been said that dependency benefits were to be eliminated under a package of changes to the UC system approved by the Unemployment Compensation Advisory Council (UCAC) in 2006 but never brought to the General Assembly. However, that package also included improvements in benefits. These benefit improvements included permitting more low-wage, part-time workers to qualify by easing the monetary eligibility standard, and setting the single maximum benefit level higher than the level called for in HB 620. This bill does not offer such improvements.

The bill also freezes maximum weekly benefits at half the average wage, or a projected $450 a week, until after the unemployment trust fund becomes solvent. According to the LSC fiscal note, the fund is projected to reach the solvency target set in the bill in 2025 without a recession, and by 2028 with one moderate recession. As much as we do not want recessions, getting to 2025 without a recession would be unprecedented in U.S. history, so the scenario including the recession is more relevant. The LSC estimated that without the benefit freeze, the maximum would rise to $553 by 2025 and $599 by 2028. This is a major cut.

For at least the last 15 years, a smaller share of unemployed Ohioans has qualified for benefits than in the nation as a whole. We require that workers earn more than in almost any other state in order to qualify—in effect, 30 hours a week at the minimum wage, averaged over at least 20 weeks. We deny benefits to jobless Ohioans seeking part-time work, even if they are seeking the same jobs they were laid off from, and even though their employers paid taxes on their wages. As ODJFS told the House committee studying the UC solvency issue in 2014, “Simply put, it is already more difficult to qualify for unemployment benefits in Ohio than in most states.” Relatively fewer jobless Ohioans exhaust their UC benefits than in the vast majority of states, and the average time workers receive benefits is also below the national average. These are some of the reasons that our overall benefit costs are below average. They are also reasons why cutting the maximum weeks available does not square with the realities of our UC system.

Ongoing benefit levels are not the main source for Ohio’s weak UC trust fund; inadequate taxes are. This was the conclusion of Dr. Wayne Vroman of the Urban Institute, who analyzed the solvency issue for ODJFS, and it is proven out by the numbers. Our taxes as a share of wages are below those of every neighboring state and the nation as a whole. State UC taxes nationally amount on average to 19 cents an hour out of the private-sector total hourly wage and benefit costs of more than $32, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. While the bill calls for tax increases, it would still leave the wages that are taxable at just $11,000, well below the national average of more than $13,500 or the $14,000-plus that Ohio would be if it had just adjusted this amount by inflation since the amount was last raised in 1995.

The bill also would not fix other flaws in the tax system that undermine its effectiveness. For instance, a component of every employer’s unemployment tax known as the “mutualized rate” incongruously has been set at zero for four years. This portion of the tax covers benefits that can’t be assigned to a specific employer, such as those that are paid to employees if their employer goes out of business. Many employers would probably be surprised to find out that, under Ohio law, the added federal tax they paid to defray the U.S. debt resulted in a reduction in this portion of their state unemployment tax. Half of the extra state solvency tax employers pay also is diverted into the mutualized account, keeping that rate down. These elements of the statute do not make sense. Yet the bill does not fix them.

The bill also would set a solvency target below that of the previous bill, and one that as of now would be well below the amount called for in current law. According to the LSC fiscal note, the projected minimum safe level in 2017 would be $2.07 billion under the bill, compared to $3.02 billion under current law.

It is good to see that HB 620 does not include some of the onerous provisions that were in House Bill 394, such as the Social Security offset, the disqualification from benefits for violating the employee handbook, and new requirements for additional work and waiting weeks for those who find themselves out of work more than once in a year. However, other provisions that do not relate to solvency have been included in HB 620. These provisions should also be jettisoned – such as redefining “just cause,” expanding time periods for collection of overpayments, permitting UC hearings to be postponed at the request of employers, but not at the request of claimants, and allowing one party to participate in a hearing by telephone. We are glad to see that the bill calls for reactivation of the UCAC, and these issues should be referred there.

House Bill 620 needs significant changes. Unemployed workers should not have to pay four-fifths of the cost of making the UC trust fund solvent. We urge you to make the needed changes and come up with a balanced plan, or leave this for the next session.

Thank you for allowing me to testify on this legislation. I am happy to answer any questions that you may have.

###

Policy Matters Ohio is a nonprofit, non-partisan research institute

with offices in Cleveland and Columbus.

Photo Gallery

1 of 22