Demanding better energy information

September 17, 2012

Demanding better energy information

September 17, 2012

Download reportPress releaseProviding renters, buyers, owners, and operators of buildings with better information related to building energy use enables them to make more informed choices, differentiate between otherwise comparable properties, and make determinations about whether energy upgrades are warranted.

Cities address market failure for energy upgrades

Despite clear economic and environmental gains from investment in the efficiency of our homes and businesses, few people are adopting efficiency measures. The benefits of these measures include saving energy and money, making  home ownership more affordable by lowering energy bills, reducing waste of scarce resources, increasing the value of existing buildings through upgrades, and reducing emissions. For the community as a whole, expanding this work can stimulate the economy and put people to work in good paying jobs. But efficiency-program uptake has been low even where generous rebates and loan programs are in place. On average, efficiency programs offered by utility companies are reaching less than 0.1 percent of all customers in their service territory.[1]

home ownership more affordable by lowering energy bills, reducing waste of scarce resources, increasing the value of existing buildings through upgrades, and reducing emissions. For the community as a whole, expanding this work can stimulate the economy and put people to work in good paying jobs. But efficiency-program uptake has been low even where generous rebates and loan programs are in place. On average, efficiency programs offered by utility companies are reaching less than 0.1 percent of all customers in their service territory.[1]

Barriers to adopting efficiency measures

The lack of efficiency program uptake has led to a national discussion among energy advocates, policy makers, and others about why people don’t take more advantage of these opportunities. Those discussions have identified several barriers to large-scale adoption of efficiency measures, including:

- Failure in the market to value energy savings, primarily due to lack of information;

- Lack of access to capital to fund efficiency-related improvements;

- Lack of consumer knowledge on cost effective improvements and reliable contractors;

- Disruption caused by renovation and construction;

- Split incentives in rental properties—property owners don’t pay energy bills and don’t directly benefit from energy upgrades;

- Uncertainty in length of tenancy/ownership, calling into question the return on investment whether owner will occupy property long enough to recoup investment on larger improvements with longer payback periods. [2]

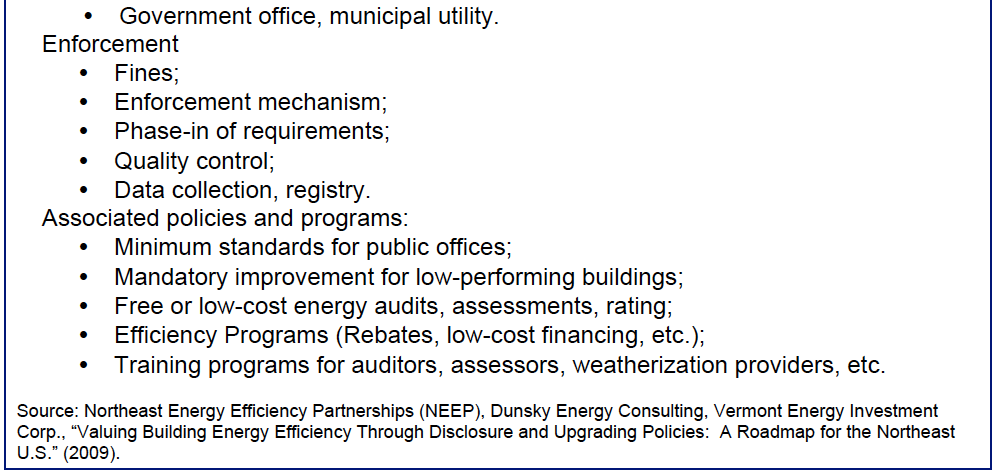

Disclosure policies

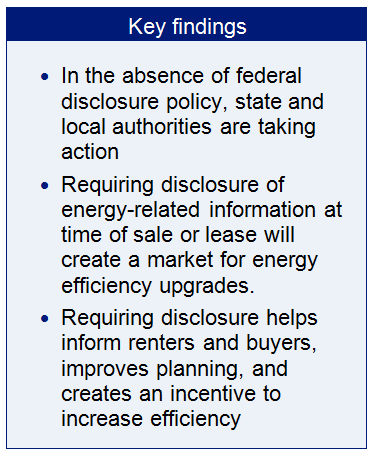

Arming renters, buyers, owners, and operators of buildings with better information related to building energy use enables them to make more informed choices, better differentiate between otherwise comparable properties, and make determinations about whether energy upgrades are warranted. In order to encourage sharing of such information, particularly at the time of sale or lease of a building, a number of state and local governments are implementing or considering implementing “point-of-sale” disclosure requirements related to building energy use.

Research suggests when information is available to consumers they are more likely to choose energy-efficient properties. Those properties also sell or lease for higher rates than their less efficient counterparts. In other words, when consumers can compare efficiency of different properties, they prefer efficient properties and the value of efficient buildings increases.[3] Ohio and its municipalities should require that sellers and landlords disclose information to potential buyers or renters regarding building energy use, previous energy bills, energy assessments and audits, or home energy ratings. This would create incentives to improve property efficiency and make buildings more attractive.[4] When buyers know that a property’s energy costs are high, they can ask the seller to improve the property or negotiate a lower price and do the work themselves.[5]

More than 30 countries have some form of energy disclosure or rating requirement.[6] The U.S. currently has no federal requirement (although when federal agencies lease space, the buildings must be rated efficient). In the absence of federal policy, state and local jurisdictions are taking action. Some require rating or disclosure at regular intervals or when a property is being sold or leased, others require reporting to the government or posting of information on a public web site.

Unlike most green building codes that require higher standards for new buildings, these requirements target existing buildings, the vast majority of our housing stock.[7] The requirements motivate sellers and landlords to upgrade existing properties; empower tenants to save money on utility bills; help owners manage energy use; help energy service companies identify customers; create transparency and support accountability in building energy performance; and, focus the community on reducing energy consumption.[8]

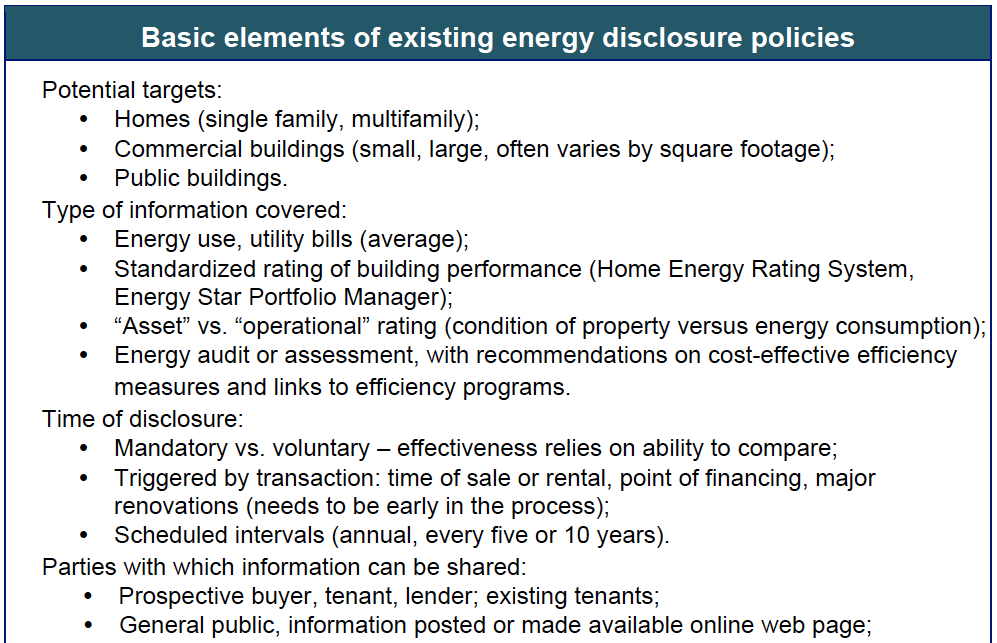

The following pages provide basic elements of existing energy disclosure policies and short descriptions of policies adopted in the U.S.

Austin, Texas (2008)

In an effort to ensure that issues would be resolved through dialogue and compromise, the city of Austin based its law on recommendations made by a taskforce of 25 stakeholders that included potential opponents of the legislation.[9] The Austin Board of Realtors, for example, opposed mandatory upgrades based on property rights policy, so the city based the law on disclosures. The Building Owners and Managers Association was concerned that any one set of prescriptive measures would not make sense for all commercial buildings since the commercial building stock is diverse. However, the group liked the idea of benchmarking under Energy Star, an accepted rating system. By basing law on the taskforce’s recommendations, the city created trust among stakeholder groups, and those groups then educated their members. The stakeholders continued advising the city to ensure smooth implementation and to resolve problems. Ongoing dialogue resulted in an update to the law in 2011.

Basic elements of the Austin energy disclosure law

- Residential – Homes and apartment complexes older than 10 years must conduct an energy audit, disclose results to prospective buyers and tenants, and send reports to the city’s municipal utility, Austin Energy. The results of apartment complex audits must be posted; particularly high energy-using complexes will be required to reduce energy use by 20 percent and disclose to prospective tenants their designation as a high energy-using building compared to similar properties (where energy use is greater than 150 percent of average energy use). Owners of four or fewer condominiums must meet residential requirements, while owners of five or more condominium units must meet multi-family requirements.

- Non-industrial commercial buildings – If older than 10 years, commercial buildings are required, starting in June 2012, to determine their operational energy rating annually (using EPA Energy Star’s portfolio manager or Austin’s energy rating system), disclose the ratings, and file them with the municipal utility.

- The role of Austin Energy – The municipal utility connects buyers and sellers to utility programs that can help cover the costs of retrofits. The utility provides low-cost loans and rebates, makes auditors available, tracks compliance and reports violations to the Austin legal department.

- Time of disclosure – The legislation was amended in 2011 to require disclosure at least three days before the end of the option period during which buyers can cancel the contract.

Documented outcomes

There have been several positive outcomes from the policy changes in Austin. In two years, over 4,000 homes have been audited, and 40 percent of the buildings that fall under compliance standards in the commercial sector have been rated. Participation in Austin Energy’s building efficiency programs has significantly increased, and efficiency conversations are moving past superficial measures to deeper retrofits such as attic insulation.

Other state and local jurisdictions

Arlington County, Virginia – In an effort to lead by example, Arlington County voluntarily began posting annual rating and energy data from county facilities on a public web site, in the form of building report cards.[10] (http://www.arlingtonva.us/portals/topics/aire/BuildingEnergy.aspx).

Burlington, Vermont – The “Time of Sale Efficiency” ordinance applies minimum standards to rental properties where tenants pay heating costs, triggered at the time of sale.[11]

Montgomery County, Maryland – Requires sellers to disclose residential utility bills to prospective buyers before closing.[12]

California (2007) – The state of California requires all non-residential buildings to disclose their building energy rating when the building is financed, sold or leased (using Energy Star Portfolio Manager).[13] Building owners can increase their energy rating by conducting an energy audit and implementing recommended measures. Draft regulations had an initial compliance date of January, 2012.[14]

San Francisco (2011) – The “Existing Commercial Building Energy Performance” ordinance expands on state law to require annual Energy Star ratings, public posting of data, disclosure to the City’s Dept. of Environment, and energy audits every five years. [15] The law applies to buildings over 5,000 sq. ft.

The state of Washington (2009) – The “Efficiency First” bill requires commercial building rating and disclosure when a sales contract or lease is presented to a prospective buyer or renter for the entire building, or when the owner applies to a lender for building financing (beginning in 2011 for commercial buildings greater than 50,000 square feet, and January 2012 for commercial buildings greater than 10,000 square feet). [16] State agencies can only sign leases in buildings that score 75 or higher under the Energy Star Portfolio Manager (based on the new federal requirement).

Seattle (2010) – The city of Seattle passed an ordinance adding to the state’s Efficiency First bill, requiring reporting of energy performance data to the city and requiring multi-family projects to comply with data to be disclosed at the request of the tenant.[17] The city commissioned an economic impact study on the ordinance’s application to more than 8,000 buildings, which estimated energy savings of 47 million kilowatt hours each year and estimated that at least 150 jobs were created.

Washington D.C. (2006) – Washington D.C. was the first U.S. jurisdiction to require disclosure of energy ratings for commercial buildings greater than 50,000 square feet.[18] Beginning in 2012, disclosures were required to be made available to the general public through an online database. These disclosures must be made whether or not the property is involved in any real estate or financial transaction.

New York City (2009) – The six parts of “The Greener, Greater Buildings Plan” are aimed at increasing the efficiency of city-owned, large commercial and residential multi-family buildings (50,000 square feet), including annual benchmarking and on-line public disclosure (beginning September 2012), and energy audits every 10 years. [19] The city is also implementing a related training program in audits, upgrades, and new construction, and has established a fund to help owners comply with new rules.

Under consideration – Other state and local governments are considering energy rating and disclosure bills, including: Colorado, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Mexico, Oregon, Portland, Tennessee and Vermont.[20]

Federal policy

Requirement for federal agencies – The 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act mandates that federal agencies lease space in efficient buildings. The space must be rated under the Energy Star labeling program and achieve a scoring of 75 or higher. [21] After the Australian government adopted a comparable policy, a similar standard ultimately became the norm in the country’s private market.

Current federal policy debate in the legislature – A new energy disclosure policy proposal is being discussed at the federal level, based on an idea supported by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. The proposal would require projected average utility energy costs of the property to be factored into a mortgage appraisal when federal financing is involved. Factoring in energy costs can result in better mortgage values for energy-efficient properties. The proposal may secure bipartisan support because it can spur efficiency at no cost to the government.

As proposed in climate change legislation – The American Clean Energy Security Act, if it had passed, would have created a building energy-performance labeling program for commercial and residential properties.[22] States that required energy assessments and labeling would have received federal funding for implementation and enforcement.

[1] Merrian Fuller, “Enabling Investments in Energy Efficiency” (May 2009).

[2] Northeast Energy Efficiency Partnerships (NEEP), Dunsky Energy Consulting, Vermont Energy Investment Corp., “Valuing Building Energy Efficiency Through Disclosure and Upgrading Policies: A Roadmap for the Northeast U.S.” (2009). Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, “Driving Demand for Home Energy Improvements” (September 2010) at http://drivingdemand.lbl.gov/.

[3] Institute for Market Transportation and Natural Resource Defense Council, “The Future of Building Energy Rating and Disclosure Mandates: What Europe can Learn from the United States.”

[4] Merrian Fuller, Energy & Resources Group, U.C. Berkeley, for Efficiency Vermont, “Enabling Investments in Energy Efficiency” (May 2009). Northeast Energy Efficiency Partnerships (NEEP), Dunsky Energy Consulting, Vermont Energy Investment Corp., “Valuing Building Energy Efficiency Through Disclosure and Upgrading Policies: A Roadmap for the Northeast U.S.” (2009).

[5] Climate Leadership Academy Network, Case Study: Austin, Texas, “Using Energy Information Disclosure to Promote Retrofitting” (June 2010).

[6] Institute for Market Transportation and Natural Resource Defense Council, “The Future of Building Energy Rating and Disclosure Mandates: What Europe can Learn from the United States.”

[7] Ibid.

[8] Institute for Market Transformation, Introduction to Commercial Energy Rating and Disclosure Policy, at www.imt.org/files/FileUpload/files/Benchmark/IMT_Rating_Intro.pdf.

[9] See Climate Leadership Academy Network, Case Study: Austin, Texas, “Using Energy Information Disclosure to Promote Retrofitting” (June 2010), and http://bit.ly/Pam6en.

[10] Institute for Market Transportation and Natural Resource Defense Council, “The Future of Building Energy Rating and Disclosure Mandates: What Europe can Learn from the United States.”

[12] Institute for Market Transportation and Natural Resource Defense Council, “The Future of Building Energy Rating and Disclosure Mandates: What Europe can Learn from the United States.”

[13] Brief description of the law at http://www.ab1103.com, retrieved July, 16, 2012.

[19] See www.energydisclosure.com; and, Institute for Market Transportation and Natural Resource Defense Council, “The Future of Building Energy Rating and Disclosure Mandates: What Europe can Learn from the United States.”

[20] Jason Mandler, GlobeSt.com Blog Network, “Energy Disclosure Laws - A Nationwide Trend in Transparency” (August 5, 2011)

Tags

2012Photo Gallery

1 of 22