When a vacant lot goes green

September 15, 2015

When a vacant lot goes green

September 15, 2015

Contact: Amy Hanauer, 216.361.9801

By Marcia Brown

Executive summary

Like many counties, Cuyahoga County suffers from blight. Dilapidated properties divide neighborhoods, heighten crime, negatively affect health, and lower property values. The drag on property values not only affects neighborhoods with abandoned properties, but also surrounding areas.

Like many counties, Cuyahoga County suffers from blight. Dilapidated properties divide neighborhoods, heighten crime, negatively affect health, and lower property values. The drag on property values not only affects neighborhoods with abandoned properties, but also surrounding areas.Managing blight is essential to the county’s economic and environmental future. The county must help take the lead to meet this goal.

Blight in Cuyahoga County

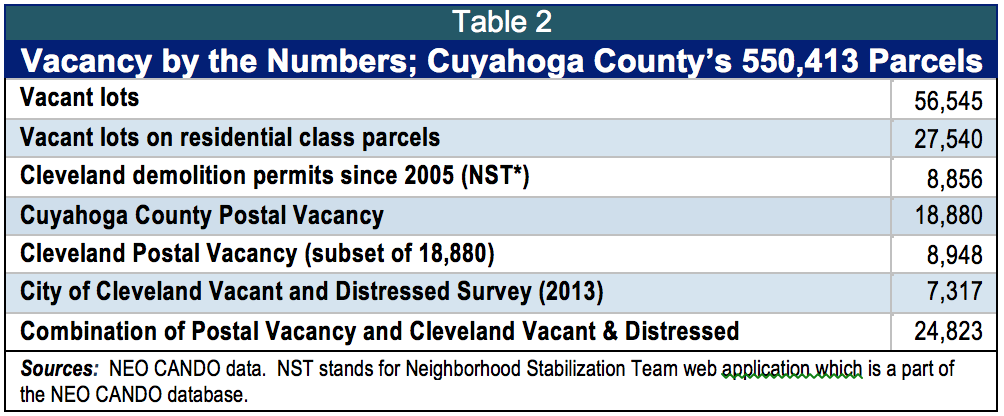

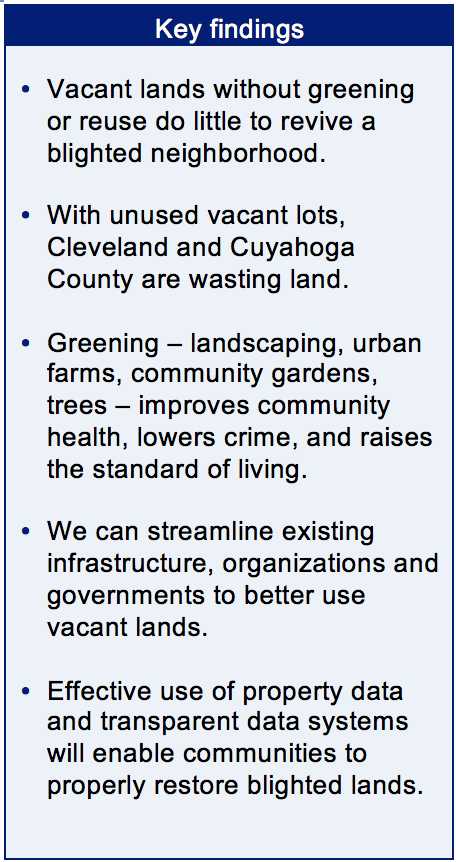

Cuyahoga County has 27,540 vacant residential class parcels, according to NEO CANDO, a data system of Case Western Reserve University that documents property data in Cuyahoga County. Some of those should be renovated and resold as homes. Some should be demolished and the land greened. But more coordination and funding is needed to manage and repurpose abandoned properties.

- Many cities suffer from population loss and a resulting drop in residency and tax revenue. In Cuyahoga County, there are more than 25,000 vacant homes with over $52 million in delinquent taxes according to NEO CANDO data. When the solution is demolition, reusing the land can enhance neighborhood life.

- Trees and greening techniques greatly revitalize communities. Greening vacant lands lowers crime, revitalizes the local economy, enhances overall health, improves land quality and raises property values.

- The use of databases for greening as well as property information is essential to effective and efficient resourse use. To combat blight efficiently, it’s essential to have comprehenseive information on vacant lands and properties. With that knowledge, vacant lands can be used for appropriate projects. For example, lots adjacent to each other can be used for an urban farms.

Funding for land banks, an essential tool for fighting blight, comes mainly from federal sources like the Hardest Hit Fund, a program of the Troubled Asset Relief Program. TARP was designed to relieve financial distress during the 2009 mortgage crisis. State and local governments can’t afford to sustain Ohio’s 22 land banks independently. More federal funding should be provided. Ohio clean energy standards and Cleveland Public Power might also offer funding for greening projects to help meet regulation standards. Furthermore, greening programs should be cohesive efforts to combat blight. This includes using a central data system such as NEO CANDO as the resource for most agencies combating blight. It’s essential that independent and government agencies work together to strategically and efficiently fight blight, rather than working independently of each other towards the same goal.

Introduction

If you live in Cuyahoga County or another urban area of Ohio, the decline in the housing stock is apparent. Decaying homes, known as blight, and vacant lands dot urban landscapes.

More than 7,317 properties in the city of Cleveland are vacant and distressed – considered likely to require demolition.[1] The nonprofit Thriving Communities Institute – part of the Western Reserve Land Conservancy -- estimates there are more than 25,000 vacant properties in Cuyahoga County.[2] Few of these lots are green spaces, a tragic loss of opportunity for their neighborhoods. Green spaces include neighborhood gardens, pocket parks, vineyards, and orchards – something more than a green lawn. Greening vacant lots deliberately and with frequent upkeep can raise the standard of living. Green spaces encourage business investment, inhibit crime, improve environmental health and maintain the community in a neighborhood.

Blight, defined as dilapidated or hazardous properties or vacant lots in an urban area, afflicts cities facing declining populations and shrinking tax bases. Cleveland, Youngstown and Steubenville are targeting blight to elevate property values and reduce crime. Nonprofit, private, and government initiatives combined are outlining plans for blight removal.But a more robust effort is needed, including an increase in federal funding, better data collection and better oversight. In the aftermath of years of population loss to urban centers, especially rust belt cities, and the 2009 crash in the housing market, foreclosures boomed, leading to more blight.

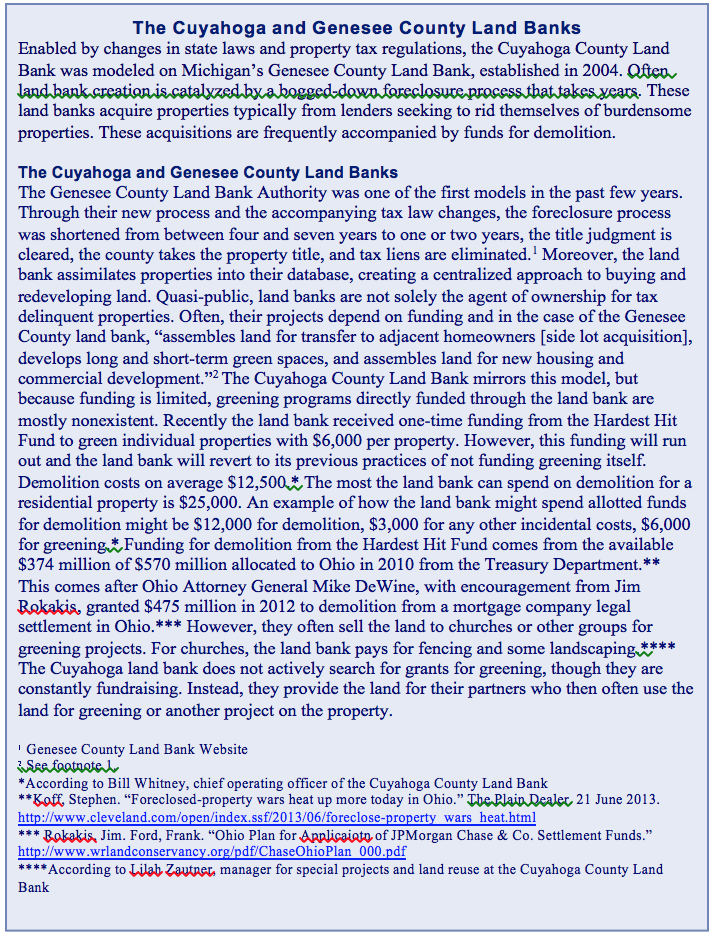

There are two types of possible foreclosures: tax delinquency and mortgage delinquency. When a homeowner does not pay taxes, the property eventually becomes city or county property. These properties frequently become part of the land bank’s acquisitions. Mortgage delinquency payments don’t automatically become city property, but often the lender will give the properties to the county land bank along with demolition money. In some cases, usually when the land bank has enough money and property seems viable, the land bank may rehab the property.

Once a residential structure is removed, the land ought to be repurposed. Leaving nature untempered does little to revitalize the neighborhood; a forgotten property implies the same sense of carelessness and hopelessness as a vacant structure. Both forms of blight depress a neighborhood. Removing the dilapidated structure is the first step. Repurposing the land, even temporarily in the hopes of investment and reconstruction, is essential to maintaining neighborhood viability.

Best practices to repurpose vacant land are outlined in this paper. Organizations across the country and in Northeast Ohio are implementing blight control tactics and making concerted efforts to improve their neighborhoods. While the problem is improving, the housing bubble and resulting 2009 collapse resulted in an exacerbated problem that coordinated efforts are still struggling to combat.

In Cleveland, the Vacant and Abandoned Properties Council (VAPAC) is leading the blight removal efforts. Assembled from a variety of community leaders, government offices, and devoted nonprofits, VAPAC’s “origins can be traced back to a June 2005 report by the National Vacant Properties Campaign titled 'Cleveland at the Crossroads', which suggested strategies to combat the city’s growing abandoned-property problem.”[3] Frank Ford, senior policy adviser for Thriving Communities Institute, chairs this committee. In addition, the Cuyahoga County Land Bank and the county’s new deputy director of housing, Ken Surratt, will take the lead in planning and implementing blight control.

“In a healthy market, the market itself takes care of blight management,” said Ford. “In Ohio, many communities are still struggling to restore median home sale prices that fell due to the foreclosure crisis.” Median home sale prices in 2014 in Cleveland were 31 percent of their 2005 peak value citywide and only 22 percent on the east side, Ford wrote.

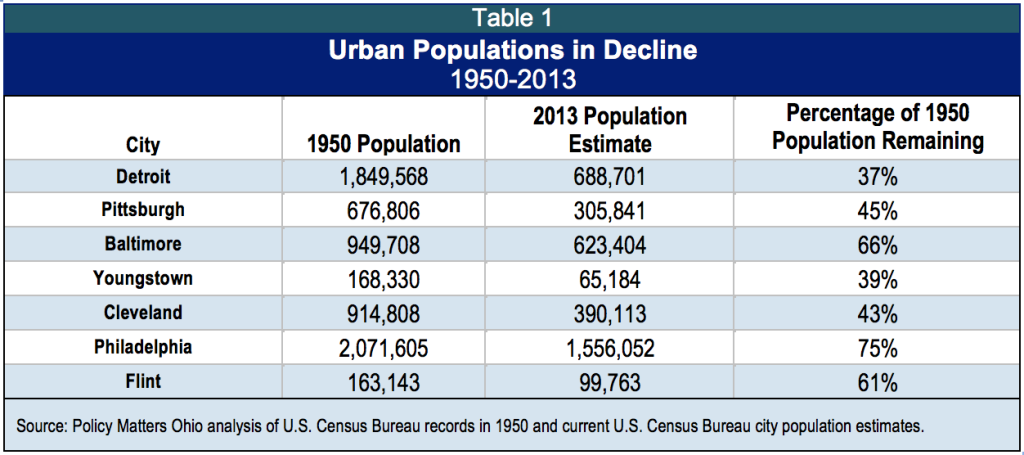

Cuyahoga County’s blight crisis and the resulting loss in tax revenue mirrors other rust belt cities in a post-industrial era. Other cities face populations a fraction of what they once were, even as national population has more than doubled.

A number of suburbs in Cuyahoga County, including South Euclid, Parma and Shaker Heights, have taken steps to address abandoned houses, according to an Aug. 16, 2015 report in The Plain Dealer.

Effectively removing blight

Removing blight falls into five major categories: mothballing, demolition, deconstruction, a hybrid demolition-deconstruction model that conserves more of the material, and renovation or reuse. Left untouched, blight can spread throughout neighborhoods, blemishing cities and rendering them unsafe. Removing or addressing blight with specific plans – even just mentioning that there is a plan to combat nearby blight – significantly improves properties’ market values and buyers’ willingness to make an investment.[4]

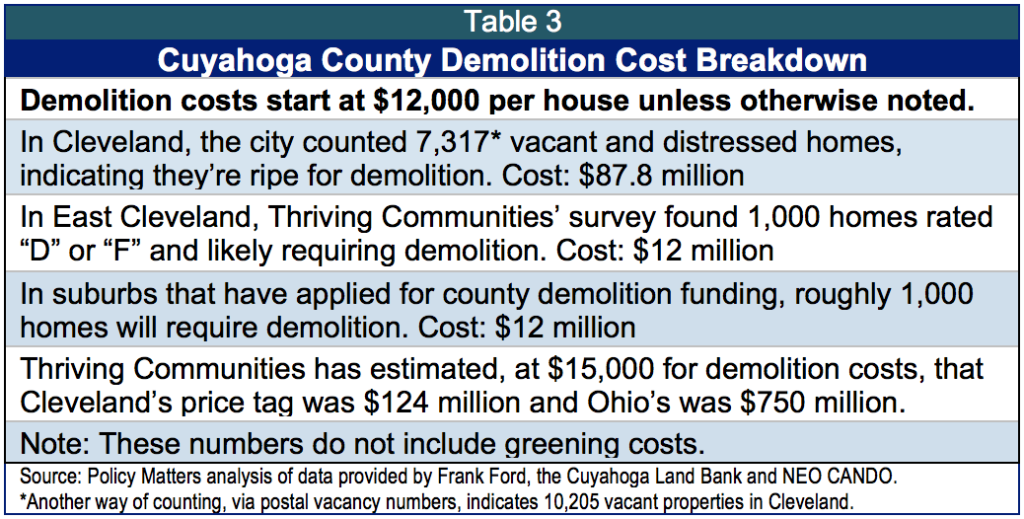

- Demolition: Cost estimates for demolition vary. For the Cuyahoga County Land Bank to tear down a structure, it spends on average $12,500, for an asbestos survey and needed remediation, and around $1,000 to remove trash before demolition.[5] Demolition removes a property using mostly heavy machinery and can require prior permission from the local or state environmental protection agency.

- Deconstruction: This method consists of taking apart a structure by hand to preserve some of the materials for reuse or recycling. It requires more time and money. Detroit’s Time to End Blight website states deconstruction differs from demolition in recycling “as much of the removed material as possible.”[6]

- Hybrid demolition deconstruction: Elements of this model are sometimes used when a city or land bank removes a blighted property. It usually consists of hand deconstruction before complete demolition via machine. It is more costly than demolition, but less costly than deconstructing the entire building.

- Mothballing: Often used for buildings with historic value, mothballing preserves a building when there is no funding to restore it. Sometimes hazardous buildings are mothballed when there is no funding for demolition. To effectively mothball a property, the organization should document the building’s assets and significance, structurally stabilize the building, and secure the structure while maintaining it until funding becomes available for the building’s future.[7]

- Renovation or reuse: Very broadly, this determines the future of a property or structure for housing or commercial development. Often, the property is converted to apartments in the hopes it can be sold for a profit. Bought for $1 in Cuyahoga County from the land bank, developers will often spend more than $50,000 to convert or renovate a property that is structurally sound and aesthetically pleasing.[8]

In the early years of blight removal, “blight” was often a euphemism for removing undesirable populations because their presence was considered synonymous with an area’s economic downturn. This specifically harmed black populations across the Midwest. Take Detroit during Mayor Edward Jeffries’ tenure between 1940 and 1948 when the city razed 100 blighted acres for redevelopment. Instead, “7,000 black residents who were displaced moved to neighboring areas where whites, in turn, left.”[9] Today, blight adheres more closely to its definition of a structural or physical hazard.

While some cities see revivals in some neighborhoods, populations remain below their historic levels. Many believe they may never fully revive. A city like Detroit, where entire vacant blocks are razed because they are hazardous to the surrounding community, and where once-splendid centerpiece buildings stand hollow and defenseless against the elements, is an example.[10] Cleveland faces a similar population drop and the resulting crisis. But in both Cleveland and Detroit, leaders are combating blight. In Detroit, led by the Detroit Blight Removal Task Force, and in Cleveland, led by the Vacant and Abandoned Properties Council (VAPAC), combatting blight is central to the cities’ future.

In Cleveland and Cuyahoga County, estimates for the number of homes slated for demolition illustrate the high costs for cities. Residential blight does not include large commercial properties, which also take a toll. Not only do cities face a loss in property tax revenue, blight also lowers property values for even those paying their taxes. Furthermore, cities must continue providing services even to blocks with few remaining residents when blight has ravaged streets. Table 3 illustrates some costs.

Select cities’ blight crises are detailed in the following paragraphs.

Cleveland: Propelled by Thriving Communities Institute’s Jim Rokakis and VAPAC, Cleveland established the Cuyahoga County Land Bank in 2006 after changes to Ohio’s laws. The land bank possesses, sells, demolishes and in other ways cares for the vacant and abandoned properties in Cleveland. Modeled off of the Genesee County Land Bank in Michigan, the land bank razes homes using funding from the lender among other sources such as the federal Hardest Hit Fund. The deal allows the land bank to take the property off the lenders’ hands in exchange for demolition costs. Led and coordinated by VAPAC, assembled of various community, philanthropic and civic leaders, the mission to combat blight in Cleveland and the county addresses both residential and commercial structures through demolition, renovation, mothballing and reuse.

Pittsburgh: When a booming steel industry fell, the city reimagined itself in the 1960s and 70s, redesigning its downtown area.[11] Today, the city has recovered somewhat, though pockets of poverty and blight remain. There are 26,140 properties that are tax delinquent for more than two years in Pittsburgh and are thus eligible for land bank acquisition. An additional 13,000 properties “are privately owned and tax-delinquent for at least two years, many of them vacant.”[12]

Youngstown: The city had 22,000 vacant properties and structures in 2013 with an estimated 130 added each year.[13] Youngstown re-envisioned itself in its “Youngstown 2010” plan. The city will resize itself for a smaller population. However, after the neighborhood planner retired in 2009, the city hasn’t yet hired anyone else.[14] Like other cities afflicted with blight, many city services are difficult to provide for a sprawled population with a diminished tax base. For example, as is the case for many blighted cities, three houses in a block far from the city center are left occupied and the city must provide services to three residents instead of the previous 20 or more on the block, making it very cost inefficient.

Flint: A model for many rust belt cities, Genesee County Land Bank is leading the charge against urban blight in Flint and the surrounding county. Once known as “Vehicle City,” with the loss of some General Motors factories, Flint’s employment fell dramatically. In Flint’s plan to combat blight, they say vacant lot reuse is “necessary and actually offer(s) opportunities for healthier and more sustainable neighborhoods.”[15] This master plan, “Imagine Flint,” cites 6,000 properties in Flint consisting of blighted structures with another 14,000 properties being vacant lots in 2014. In total, it lists 20,059 properties in need of blight elimination over the next five years.[16]

Philadelphia: Many cities are going broke from the costs of services spread over a sprawled city with a declining population and a shrinking tax base. Philadelphia’s 2010 study estimated these costs total $20 million each year in city services, in addition to the $2 million lost in tax revenue from the 17,000 vacant tax-delinquent properties.[17] Cities like Philadelphia are facing a twofold challenge. As blight expands, property values drop so residents pay fewer taxes. But as property values drop low enough that residents’ mortgages are more expensive than the house, residents abandon their homes, increasing blight. Further, when few houses remain occupied but city services are still demanded, the financial strain on the city increases.

Detroit: Detroit faces one of the worst blight outbreaks in its shrinking community. After seeing its population decline drastically, Detroit needs to condense its city services while keeping its land green and vibrant. In “Every Neighborhood Has A Future . . . And It Doesn’t Include Blight,” Detroit laid out its June 2014 plan with input from community leaders, local, state and federal levels of government, nonprofits and businesses both large and small. After surveying properties through Motor City Mapping software and community volunteer efforts, the Task Force documented 40,077 structures that met the Task Force definition of blight, 38,429 structures with indicators of future blight and 6,135 blighted vacant lots. This totals an $850 million price tag for Detroit to address blight.[18] To meet this demand, Detroit’s Task Force is utilizing a comprehensive database in Motor City Mapping, an army of volunteer surveyors, nonprofits, community leaders and a strong city government “to address every blighted structure in the entire city as quickly as possible, as well as to clear every neglected vacant lot.”[19]

Greening techniques and the people who champion them

After a structure is razed, be it commercial or residential, the vacant land is available for various uses. Often, churches and community organizations undertake greening projects such as urban farms, orchards, greenhouses or gardens. Some nonprofits are planting trees on vacant lots. Unfortunately, funding for these efforts is minimal to nonexistent. Many of these programs rely on volunteers. Side-yard acquisition programs are often the most common for land banks. Residents living next door to a vacant lot undertake a project, often a greening project, and purchase the land next door for that use. It’s ideal that private money go towards projects with numerous direct and indirect benefits. However, under new Ohio laws, it is becoming harder for the land bank to sell properties to individuals.[20] Not all projects are greening projects. Some parcels are acquired for recreation, redevelopment or another project.

Common greening methods include urban farming or community gardening, landscaping, planting trees or other foliage, or greenhouses. As previously mentioned, greening benefits the lot and surrounding area. Improving property values through demolition or greening has a positive effect. Every county resident has a vested interest in maintaining property values in the county.[21] Greening vacant lots can also make residents feel safer from violent crime.[22] Trees can actually lower violent crime rates. According to a study on Baltimore, “neighborhoods with 10 percent more tree canopy cover experienced 11.8 percent less crime than their comparable counterparts after adjusting for numerous socioeconomic and housing factors.”[23]

Greening vacant lots is a growing trend in vacant land reuse, across Northeast Ohio and throughout the county. Thriving Communities Institute is leading the tree planting efforts. Jim Rokakis, former Cuyahoga County treasurer, heads this nonprofit and is one of the strongest voices nationally on combatting blight. He was instrumental in the fight for changes in Ohio law and tax regulations necessary for the establishment of the Cuyahoga County Land Reutilization Corp -- the full name of the Cuyahoga County Land Bank. The Institute champions greening for all vacant lands, brownfields and greenfields.[24]

Ford, senior policy adviser at Thriving Communities Institute, believes that blight management is essential to reviving a stalling market. “The purpose of demolition is to remove enough market-crippling blight to enable the housing market to recover,” said Ford. “As the market recovers, demolition activity will be replaced by renovation.”

Because there is little funding directly targeted for greening efforts, finding the resources to sufficiently facilitate this effort requires public dollars. Some communities have used funds from the federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act to provide new training. In New York City, nonprofits, prisons, and city programs work together to train inmates to plant trees and tend gardens.[25]

Urban farming: This prospect has the capacity to be profitable if farmers can find their niche in the market by growing unique, high-demand crops. Often, the farmers sell to local restaurants and have a place in the local farmers market. According to Conor Willis, who helped run an urban farm in Albuquerque, New Mexico, one person per acre is needed to farm urban land in a profitable, self-sustaining way. The six-acre urban farm in Ohio City has been relatively successful, in part due to its management by multiple agents such as Ohio City Incorporated and the Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority.[26] Volunteer and community efforts are typically more successful than individual efforts. According to Dana Hilfiger, who works on a nonprofit urban farm in Columbus, intensive farming with several plants using the same space is the best way to maximize each square foot – imperative on urban farms with limited space. She believes small-scale urban farms can be viable, but agrees that size contributes to cost-efficiency. For both urban farms and community gardens, soil health is essential. If the soil is contaminated from the previous building, then raised beds are required, hiking the cost of the garden or farm. In greening projects, Hilfinger sees zoning laws as crucial. Small, non-profit urban farms may not be viable if subjected to regulations intended for commercial developments.

Community gardens: Churches often buy land for community gardens, often through the land bank. Community gardens are often established by a motivated, organized group and operated by volunteers. Sometimes a street or neighborhood will get together to establish a community garden by adopting a vacant lot. Take the corner of Avalon and Kenyon roads in the Lomond neighborhood of Shaker Heights. Community members are applying to the city[27] to plant an orchard of apple trees, funded by $80,000 in stimulus money from the federal Neighborhood Stabilization Program. The downside of such a project is that there is not enough money and people to continue funding and running the project and the orchard may fall into disrepair.

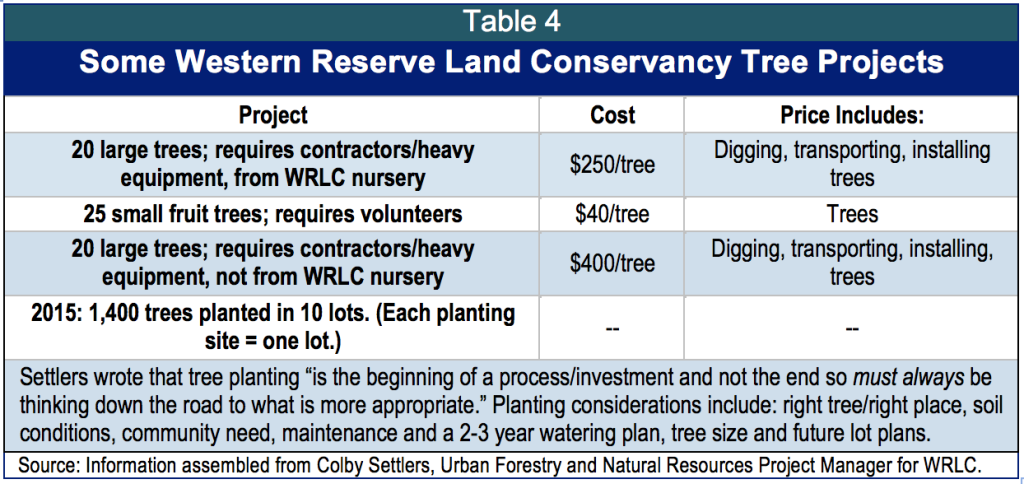

Trees: Although trees have positive effects, as a solution for vacant lands, trees are controversial. Planting and maintaining trees can be difficult to sustain. Thus, tree planting only makes sense if the land is not slated for redevelopment any time soon. However, trees can filter the air, absorb CO2, improve storm water drainage, conserve water, reduce soil erosion, save energy through their shade, and encourage economic activity.[28] Trees improve neighborhoods, encourage economic investment, and can save municipal money in storm water management. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, “[trees’] innate ability to capture storm water reduces the load on existing storm water management systems, which in turn reduces treatment costs as well as the need for additional facilities.”[29] Trees also improve human health: reducing asthma, improving lung health, and encouraging greater physical activity.[30]

General landscaping: Some cities, like Shaker Heights, do some landscaping on vacant lots after demolition. However, funding for this is often unavailable in cash-strapped cities where blight is rampant. More metropolitan areas or former industrial cities are facing larger blight crises than the inner ring suburb of Shaker Heights. Land banks, which are quasi-public, often take the role of repossessing the land rather than the city government. The land bank may not landscape every property it razes. Funding is often not available for such large-scale greening projects, even if there is funding for demolition.

Answering the call to greening with policy

While greening efforts from smaller sources, nonprofits, or individuals can help, policy change is essential to get to the scale demanded by the problem. This will allow communities to see a majority of the vacant parcels greened, not just a few stand-outs. Standardizing the pathway to green or reuse parcels will achieve greater efficiency, better use of resources, and more economies of scale.

When funding and opportunity are available, greening should be attempted. Other uses such as dog parks, play areas, or solar or wind farms can also be viable options.

Recently, the senate version of the federal highway bill threatened land bank funding to Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Indiana and more. In Ohio, $71 million of promised federal funding for land banks’ demolition projects from the Hardest Hit Fund was threatened with re-allocation to building roads and bridges. According to Jim Rokakis, without this funding some of Ohio’s 22 land banks would go bankrupt because of their possession of thousands of properties. Thanks to opposition from Ohio’s U.S. Senators, the provision was removed from the bill.

Cuyahoga County just hired its first deputy director of housing. Ken Surratt is designing a countywide housing plan that will incorporate various organizations dedicated to eliminating blight. “There are over 40 organizations being represented in the stakeholder group and we are working collaboratively to figure out what works best here in Cuyahoga County,” Surratt wrote in an email. “This will also be supported by a study being done by the Cuyahoga County Planning Commission. We will touch on numerous topics including foreclosures, blight, demolition, rehabilitation, access to capital, fair housing, etc.” The plan should be finished by spring of next year.

The land bank also created a new Buying and Retaining Academic Investment Now program designed to retain talented young people in Cleveland. This program offers students and recent graduates a “chance to purchase a newly renovated home at a discount of 15 percent off the purchase price and additional 5 percent of the purchase price to be applied to closing costs.”

Recommendations and conclusion

Several policy changes would make it easier to convert vacant properties into the kind of green spaces that enrich communities, reduce crime and improve environmental health.

- Thriving Communities Institute is advocating for more bank settlement money from the U.S. Justice Department and for a line item in the state budget for blight removal.[31] The extra funds should include resources targeted for greening. The federal Hardest Hit Fund provides just $71 million to the whole state of Ohio for demolition, when more than $100 million is needed in Cuyahoga County alone. We recommend quadrupling the Hardest Hit Fund.

- Prior to demolishing a property, cities should put in place a greening or reuse plan for the vacant land. An appropriate agency should create a menu of options for cities to ensure that land is reused. Funding for greening is not always specified in demolition funds at the federal, state, county or city level – but it should be. If the greening involves a renewable energy project, the organization sponsoring the project could apply for funding from sources like the Ohio Clean Energy Standards and Cleveland Public Power.

- Cuyahoga County is in a position to conduct the fight against blight. Greening enhances community vitality, resident well being, housing values and business investment. Recently, the county hired a deputy director of housing and community revitalization for the first time – an excellent step. In creating his housing plan, the deputy director should work closely with organizations dedicated to greening. Existing resources and infrastructure can promote blight elimination.

- Cities should more strictly enforce their codes to ensure homeowners don’t let properties disintegrate and should provide links to resources to help owners finance repairs.

- Data is key to successfully combatting blight. NEO CANDO is one of the best, if not the best, property database in the country. However, transparency and usability are not perfect. Having data accessible to the public and relevant nonprofits, agencies, governments or other organizations critical. As needed and feasible, we should consolidate data in one easily accessed place.

- Greening can provide jobs for entry-level workers. We recommend that all property revitalization efforts consider how to incorporate training, and how to access training-related funding as appropriate.

Greening enhances economic viability and neighborhood vitality Using public funds for land reuse is essential to the revitalization of neighborhoods devastated for over a decade.

[1] NEO CANDO at Case Western Reserve University

[2] Frank Ford, senior policy adviser for Thriving Communities made this estimate based on NST data in CWRU’s database. Thriving Communities Institute is completing a countywide door-to-door survey to document the state of parcels in the county. This will more accurately give a number for vacant and distressed properties. Usually, data for vacant structures is compiled from purchased U.S. postal data.

[3] Quoted from a research project by the Metropolitan Institute. College of Architecture and Urban Studies Virginia Tech, by David Morley, AICP. “Cities in Transition – Interview [with Frank Ford, now senior policy advisor for Thriving Communities Institute]” Vacant Property Research Initiative. http://vacantpropertyresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Ford_Final.pdf

[4] Perkins, Olivera. “Low-cost loft home conversions make old houses marketable, avoiding demolition.” The Plain Dealer. 30 March 2013. Web. http://www.cleveland.com/business/index.ssf/2013/03/loft_home_conversions_offer_a.html

[5] According to Bill Whitney, Chief Operating Officer of the Cuyahoga County Land Reutilization Corp.

[6] “Frequently Asked Questions.” Detroit Blight Removal Task Force, Time to End Blight. http://www.timetoendblight.com/faq/#28

[7] Park, Sharon C. “Mothballing Historic Buildings.” Technical Preservation Services, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Sept. 1993. Web.

[8] Perkins, Olivera. See footnote 6.

[9] Padnani, Amy. “Anatomy of Detroit’s Decline.” The New York Times. 8 Dec. 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2013/08/17/us/detroit-decline.html?_r=1&

[10] For further reading on Detroit’s decline, see http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2013/08/17/us/detroit-decline.html?_r=1&

[11] Ghosh, Palash. “A Tale of Three Cities: Detroit, Toronto, And Pittsburgh In A Post-Industrialized World.” International Business Times, 9 Oct. 2013. http://www.ibtimes.com/tale-three-cities-detroit-toronto-pittsburgh-post-industrialized-world-1417742

[12] Daniels, Melissa. “Proposed Pittsburgh land bank aims to end blight, speed redevelopment.” TRIB Total Media. 28 Jan. 2014. http://triblive.com/news/allegheny/5487660-74/properties-bank-tax

[13] Williams, Timothy. “Blighted Cities Prefer Razing to Rebuilding.” The New York Times. 12 Nov. 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/12/us/blighted-cities-prefer-razing-to-rebuilding.html?_r=0

[14] Denvir, Daniel. “Defending Youngstown: One City’s Struggle to Shrink and Flourish.” The Atlantic. 31 Jan. 2013. http://www.citylab.com/politics/2013/01/defending-youngstown-one-citys-struggle-shrink-and-flourish/4485/

[15] “Imagine Flint” master plan including the “Beyond Blight: City of Flint Comprehensive Blight Elimination Framework.” Blight Elimination Framework Draft II. 21 March 2014. https://app.box.com/s/ib37jbl2tgtqaue8lygc

[16] “Imagine Flint.” See footnote 16.

[17] Fraser, Jeffery. “The cost of blight: vacant and abandoned properties.” Pittsburgh Quarterly, Fall 2011. http://www.pittsburghquarterly.com/index.php/Region/the-cost-of-blight/All-Pages.html

[18] “Every Neighborhood Has A Future . . . And It Doesn’t Include Blight.” Detroit Blight Removal Task Force Plan 2nd Printing: June 2014.

[19] Detroit Task Force. See footnote 19.

[20] According to Lilah Zautner, manager of special projects and land reuse. Because of stricter requirements regarding plans for reusing vacant parcels, acquiring land as an individual has become more difficult statewide.

[21] H.B. 920 mandates that as property values rise, property taxes remain at the same level unless there is a levee – which is often the way public school districts account for lost income from inflation and a smaller percentage of tax when the property values rise.

[22] “Penn Study Finds with Vacant Lots Greened, Residents Feel Safer.” Penn Medicine, Philadelphia. 2015. Penn study conducted by Charles Branas, associate professor of Epidemiology at Penn Medicine. http://www.uphs.upenn.edu/news/news_releases/2012/08/vacant/

[23] Conniff, Richard. “Trees Shed Bad Rap As Accessories to Crime.” Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. 2012. http://environment.yale.edu/envy/stories/trees-shed-bad-wrap-as-accessories-to-crime

[24] According to an interview with Jim Rokakis and additional conversations with Kate Hydock and Rokakis following the initial interview.

[25] Walsh, Dylan. “Prisons, Then Parks: A Therapeutic Journey.” The New York Times. 2 Aug. 2011. http://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/02/prisons-then-parks-a-therapeutic-journey/?_r=1

[26] “Ohio City Farm.” Ohio City Incorporated. 2014

[27] Kamla Lewis, Shaker Heights Director of Neighborhood Revitalization, explained this project in an interview. She is also on Policy Matters Ohio’s board. It can also be found here: Feran, Tom. “Shaker Heights plans an orchard to replace a comdemned house.” The Plain Dealer. 13 April 2010. http://blog.cleveland.com/metro/2010/04/shaker_heights_plans_an_orchar.html

[28] “The Benefits of Urban Trees.” The Maryland Department of Natural Resources Forest Service. http://www.dnr.state.md.us/forests/publications/urban.html

[29] “Stormwater to Street Trees Engineering Urban Forests for Stormwater Management.” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Sept. 2013. http://water.epa.gov/polwaste/green/upload/stormwater2streettrees.pdf

[30] “Health Benefits of Urban Trees.” Southern Group of State Foresters, a nonprofit organization composed of foresters from various states. 2014. http://www.southernforests.org/urban/benefits-of-urban-trees

[31] Frank Ford provided this information in an email.

Tags

2015InternsSustainable CommunitiesPhoto Gallery

1 of 22