No Windfall: Casino taxes won’t make up cuts to local governments

October 01, 2012

No Windfall: Casino taxes won’t make up cuts to local governments

October 01, 2012

Press releaseDownload summaryDownload reportWhile any new revenue is a welcome addition to strained local budgets in Ohio, casino taxes won't come close to making up for the cuts the state has imposed on local governments and schools.

Executive summary

The opening of casinos in Cleveland and Toledo and the “racino” at Scioto Downs in Columbus means, among many other things, additional tax revenue. A third casino is scheduled to open in Columbus on Oct. 8, with a fourth to follow in Cincinnati next spring.  Any new revenue is a welcome addition to strained local budgets. However, casino revenue makes up only a fraction of the cuts that local governments recently sustained because of slashed revenue from the state and the impending end of the estate tax.

Any new revenue is a welcome addition to strained local budgets. However, casino revenue makes up only a fraction of the cuts that local governments recently sustained because of slashed revenue from the state and the impending end of the estate tax.

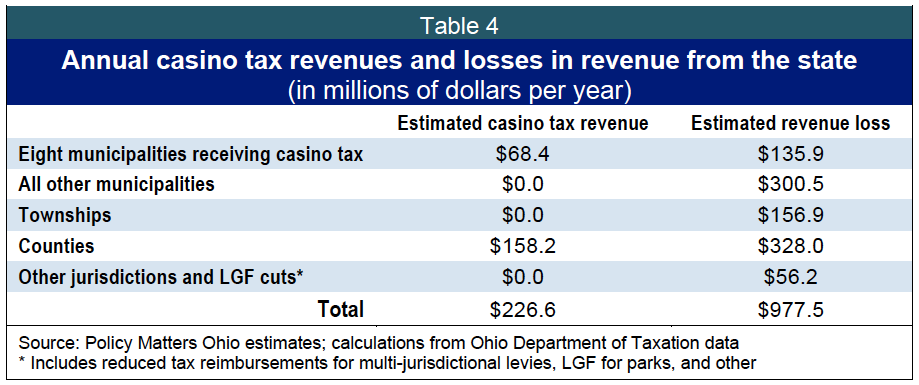

Overall, counties, cities, villages, townships and other local government jurisdictions will lose close to $1 billion a year from the cuts in state aid, not including reductions in state spending that goes to local governments for specific programs. Yet Policy Matters Ohio estimates that the casino tax is likely to provide just $227 million a year for local governments that receive it. This will go to counties, the four cities that house casinos and four other major cities. Even for these governments, the estimated amount they are to receive in casino gaming taxes on average will be only half of the revenue they are expected to lose because of the current state budget. Nor will the additional aid to school districts make up more than a fraction of state cutbacks to education funding.

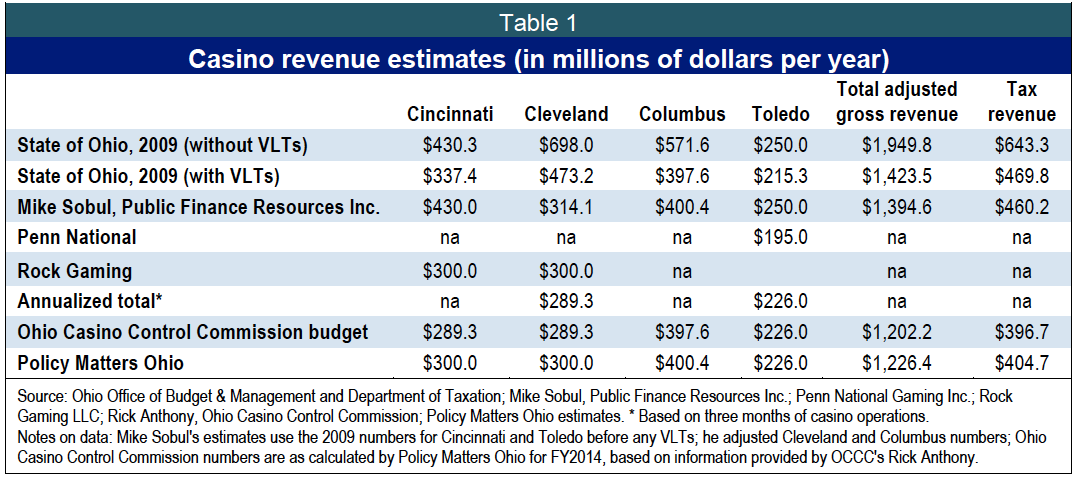

Our casino revenue estimates are necessarily tentative. Projected revenues have come down significantly since the 2009 campaign for the casino proposal, and the expected opening of numerous gambling facilities makes it hard to be sure what revenues will be. We estimate casino tax revenue based on several sources, including state agencies, casino operators, and former taxation department analyst Mike Sobul. Our numbers reflect a comparatively optimistic assessment.

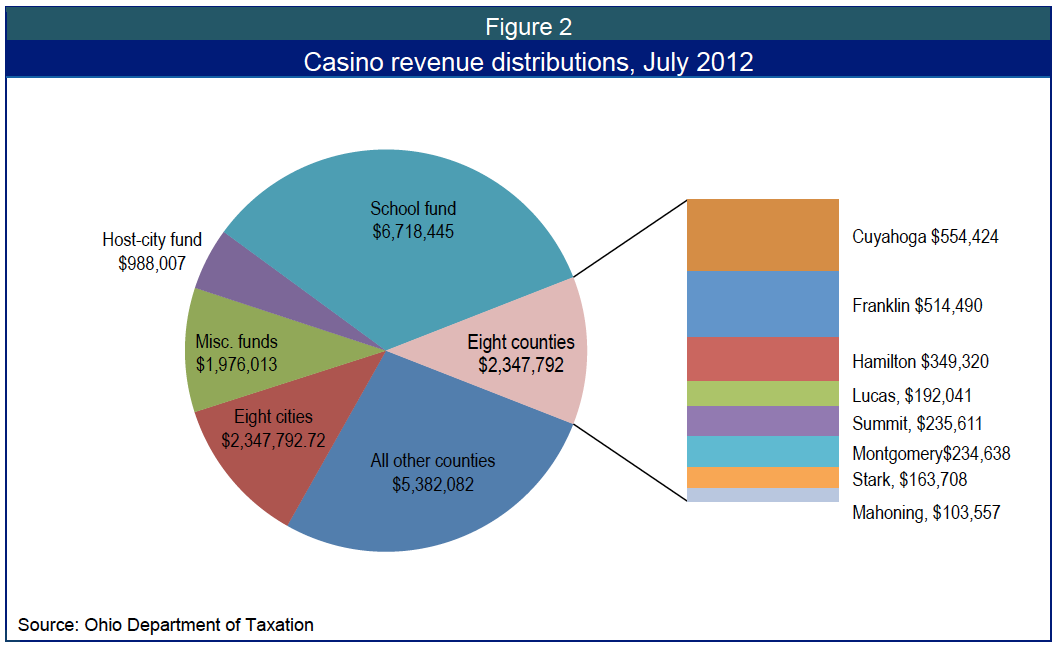

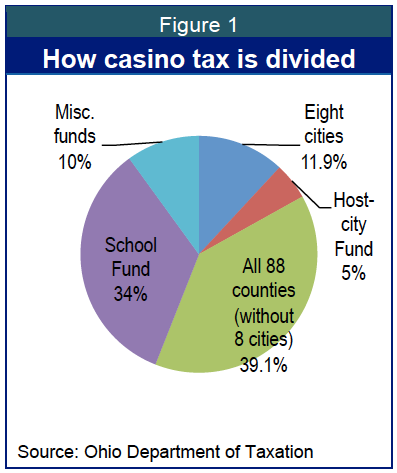

Casino taxes are set at 33 percent of gross casino revenues. Tax revenues are to be split into many pieces (see graphic, next page), with money going to school districts, counties, eight large cities, law enforcement, treatment of problem gambling, the state racing commission and the Ohio Casino Control Commission. Half of the county share where the largest city has more than 80,000 people will go to that city, and the four cities that will host casinos each will get 5 percent of that casino’s tax revenue.

Tax revenue from casinos will make up only a fraction of the $1.8 billion in state cuts to K-12 education in the current two-year budget compared to the previous biennium. According to an analysis Sobul did last May, the new tax revenue will amount to between 0.5 and 1.5 percent of operating spending in most school districts.

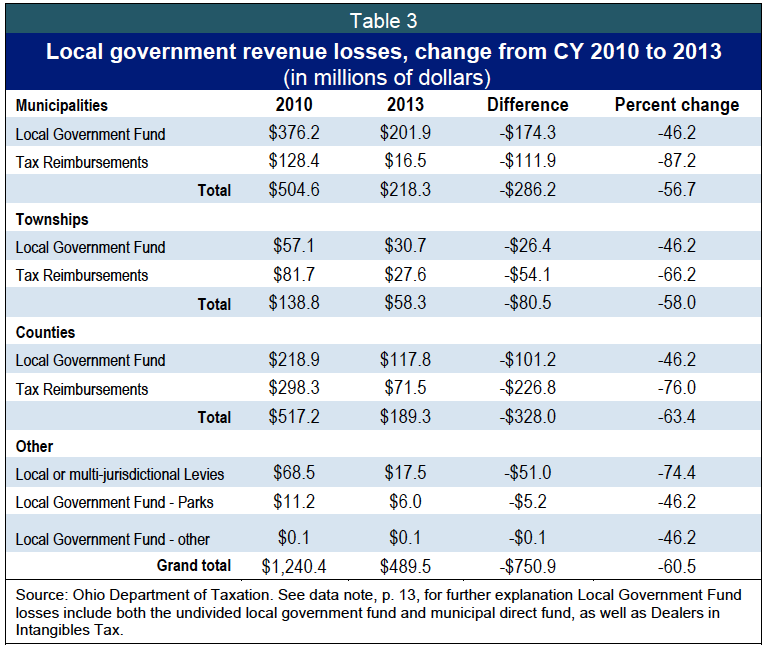

Like schools, local governments across Ohio have been hit by reductions in reimbursements the state had previously made to them for property-tax levies they lost after state policy eliminated them. These have been especially damaging to county levies that support health and human service programs. Local governments also are experiencing drastic reductions in state aid through the Local Government Fund, and municipalities and townships are about to see a decline in support because of the repeal of the estate tax, which had generated hundreds of millions of dollars annually for them.

Even those localities that will receive casino revenue are still deep in the hole based on the cuts in state aid. The four casino host cities – Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, and Toledo – will likely receive less as a group in gaming tax revenue than their 2013 loss just in local government funds. Estate tax elimination alone is likely to offset Cincinnati’s casino tax gains. It will be some time before a full accounting can be done of the full financial effects from casinos on host cities, but officials from Columbus and Cleveland have noted recently that gaming-tax revenues come nowhere near making up losses from changes in state tax policy.

Video lottery terminals (VLTs) are also opening at Ohio race tracks, licensed by the Ohio Lottery. Assuming all seven tracks add VLTs, annual revenue could be up to $338 million a year, based on the first three months of operations of Scioto Downs. This will reduce casino revenue. Unlike casino taxes, new government revenue from the racetracks will go to the lottery. Like other lottery profits, it is required to be spent on education – and somewhat similarly, the constitutional amendment enabling the casinos says that tax distributions to schools and local governments are “intended to supplement, not supplant, any funding obligations of the state.” However, as with the lottery, there is little reason to believe casino revenue will amount to a bonus over what the state would otherwise spend.

Regardless of the supplantation issue, casino revenues, while significant, go nowhere near making up for the cuts sustained by local governments from state tax policy changes made in the current state budget. Ohio needs to boost its investment in schools, local governments and human services with additional revenue from those who can afford to pay. Revenue from gambling does not suffice.

Introduction

The opening of casinos in Cleveland and Toledo and the “racino” at Scioto Downs in Columbus means, among many other things, additional tax revenue. A third casino is scheduled to open in Columbus on Oct. 8, with a fourth to follow in Cincinnati next spring. This brief reviews tax revenue that may be produced by casinos, and how that compares with state cuts to schools and local governments. Any new revenue is a welcome addition to strained local budgets. However, casino revenue makes up only a fraction of the cuts that local governments recently sustained because of slashed revenue from the state and the impending end of the estate tax.

Overall, counties, cities, villages, townships and other local government jurisdictions will lose close to $1 billion a year from the cuts in state aid (that does not include reductions in state program spending that goes to local governments for specific services). Yet Policy Matters Ohio estimates that the casino gaming tax is likely to provide just $227 million a year for local governments that receive it. This will go to counties, the four cities that house casinos and four other major cities. Even for these governments, the estimated amount they are to receive in casino gaming taxes on average will be only half of the revenue they are expected to lose because of the current state budget. Nor will the additional aid to school districts make up more than a fraction of state cutbacks to education funding.

Casino revenue estimates in this report are necessarily tentative. Projected revenues have come down significantly since the 2009 campaign on the casino proposal, and the expected opening date of numerous gambling facilities makes it hard to be sure of exactly what revenues will be.[1] This report estimates casino tax revenue based on a number of sources. These include: A 2009 report by the Ohio Department of Taxation and the Ohio Office of Budget and Management;[2] an update of that by Mike Sobul, formerly of the Ohio Department of Taxation, who oversaw the 2009 report and is now a consultant at Public Finance Resources Inc.;[3] predictions by the two Ohio casino operators, Rock Gaming LLC and Penn National Gaming Inc.;[4] the first three months of revenue as reported by the Cleveland and Toledo casinos;[5] and estimates that the Ohio Casino Control Commission (OCCC) produced recently in connection with its own budget. Rick Anthony, director of operations for the OCCC, stresses that estimates he made for that purpose are not official state numbers and should not be the basis for budget planning by others.[6] With the exception of the three-month actual totals, all estimates cover annual revenue to be produced when all four casinos are fully operating.

Gross casino revenue

Table 1 shows the estimates made by each of these observers for gross casino revenue from each of the four casinos, and the grand total of annual revenue, once all four casinos are fully operational.[7] Policy Matters Ohio’s numbers reflect a comparatively optimistic assessment. We have chosen to use numbers from three of these sources – Rock Gaming, Mike Sobul and the OCCC – in our estimate; others could certainly be used. Cuyahoga County budget officials, for instance, have come up with lower projections, in particular for the Columbus casino.[8] It is altogether possible that the first three months of operations at two Ohio casinos will not be a good indicator of long-term revenues.

Under the constitutional amendment approved by Ohio voters in 2009 that permitted the establishment of casinos in Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus and Toledo, a tax of 33 percent is levied on gross casino revenues, which is the income casinos make after paying out prizes but before paying expenses. Casino tax revenue is divided as follows:

- 51 percent goes to Ohio’s 88 counties based on their population. In those counties whose largest city had more than 80,000 people as of the 2000 Census, half of the county allocation will go to that city. Columbus, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Toledo, Akron, Canton, Dayton and Youngstown receive such revenue;

- 34 percent goes to public school districts based on student population, for primary and secondary education;

- 3 percent goes to the Ohio State Racing Commission for the horse racing industry in Ohio;

- 3 percent is used to fund the Casino Control Commission;

- 2 percent is for a state fund for the treatment of problem gambling and substance abuse, including related research;

- 2 percent goes to a state fund for training law enforcement agencies, and

- 5 percent of the tax from each individual casino goes to the host city for that casino.

Figure 1 shows the share of casino revenue that is to be distributed to school districts, counties, the eight cities that will share county revenue, the four cities with casinos, and the other funds getting the money.

Figure 1 shows the share of casino revenue that is to be distributed to school districts, counties, the eight cities that will share county revenue, the four cities with casinos, and the other funds getting the money.

During the first three full calendar months of operations beginning June 1, the Cleveland and Toledo casinos generated adjusted gross revenue (money received by the operators less winnings paid to patrons) of $72.9 million and nearly $57 million, respectively.[9] On an annualized basis, this would amount to $289.3 million from the Horseshoe Casino Cleveland and $226 million from the Hollywood Casino Toledo.

Figure 2 outlines the total amount of funds distributed in July 2012 to each of the eight counties that contain cities receiving funds.[10] The figures show what county governments received, based on a month-plus of operations at the Cleveland and Toledo casinos, which opened in May. As outlined above, these eight county governments receive half of the allocation they would get based on their share of the state’s population, with the other half going to a large city in that county.

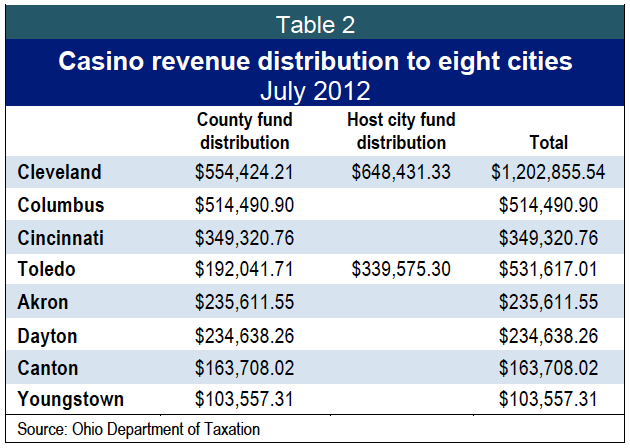

Table 2 breaks out the amounts that the eight cities eligible for casino tax received in the first quarterly distribution in July. For six of the cities, this is their half of their county’s allocation. Cleveland and Toledo, as cities with operating casinos, received a Host City Fund disbursement during this distribution. Columbus and Cincinnati will start receiving such distributions after their casinos open.

The current Ohio state budget, approved in June 2011 and covering the two years that began July 1, 2011, contained major reductions in state support to school districts and localities.[11] Funds supporting K-12 education were cut by $1.8 billion in the Fiscal Year 2012-2013 budget, compared to the previous biennium.[12]

The current Ohio state budget, approved in June 2011 and covering the two years that began July 1, 2011, contained major reductions in state support to school districts and localities.[11] Funds supporting K-12 education were cut by $1.8 billion in the Fiscal Year 2012-2013 budget, compared to the previous biennium.[12]

Mike Sobul, former taxation department analyst and now consultant, analyzed casino taxes and their likely effects on school budgets last May. Sobul noted, “While the amount of money that is estimated to be allocated to each (school) district is not insubstantial, it is also not enough in most cases to make a significant difference in financial planning.”[13] First payments, covering casino revenues this year, will go to schools at the end of January 2013. In his May 2012 analysis, Sobul estimated revenues from the four casinos, concluding that in Fiscal Year 2014 they would amount to a total of $136.36 million, or $71.77 per pupil.[14] In general, this will amount to between 0.5 percent and 1.5 percent of operating spending in most school districts, Sobul said. This also assumes that such dollars do not supplant existing state aid to school districts (see p. 13 on supplantation). In the context of state spending of $8.9 billion this fiscal year on K-12 education,[15] it is indeed a modest amount.

Altogether, local governments also saw their state support slashed by about a billion dollars during the current two-year budget compared to the previous biennium, including cuts to the Local Government Fund and reductions in state reimbursements for local property taxes that were eliminated.[16] The repeal of the estate tax, which generated $302.1 million for local governments in Fiscal Year 2011,[17] will add to the reductions felt by municipalities and townships starting next year (Eighty percent of the estate tax is distributed to local governments, while 20 percent of it goes to the state). Table 3 shows how much these local governments, as well as counties and other local-government jurisdictions, are likely to lose in revenue from cuts in the Local Government Funds and tax reimbursements in calendar year 2013 compared to calendar year 2010. Altogether, local governments are likely to lose nearly $751 million from these two sources in calendar year 2013[18] compared to what they received in 2010.

Losses from the repeal of the estate tax, effective Jan. 1, 2013, will not make themselves felt until later in 2013. Altogether, based on average estate tax distributed to cities, villages and townships between calendar years 2007 and 2010, local governments will lose a total of $226.5 million a year (we have used a four-year average since the amount changes from year to year). This includes $150.1 million for municipalities and $76.4 million for townships (counties do not receive estate tax).[19]

Anticipated casino revenues will make up only a portion of the losses to these three revenue sources for local governments that the state has reduced or eliminated. Table 4 shows projected annual casino revenues once the four establishments are fully operational, compared with lost revenue from the local government funds, tax reimbursements, and the estimated estate tax for local governments.[20]

Though counties will receive 39 percent of the casino gaming revenue, that is likely to produce just $158.2 million a year when the casinos are fully operational, compared to losses of $328 million. Cuyahoga County has projected that its overall losses from the state budget will amount to $40.2 million in calendar 2013, compared to 2010.[21] Besides the three sources already mentioned, this also includes $8.9 million in state cuts to programs. Based on our casino revenue estimates, the county would get $11.35 million a year once the casinos are fully operational.[22]

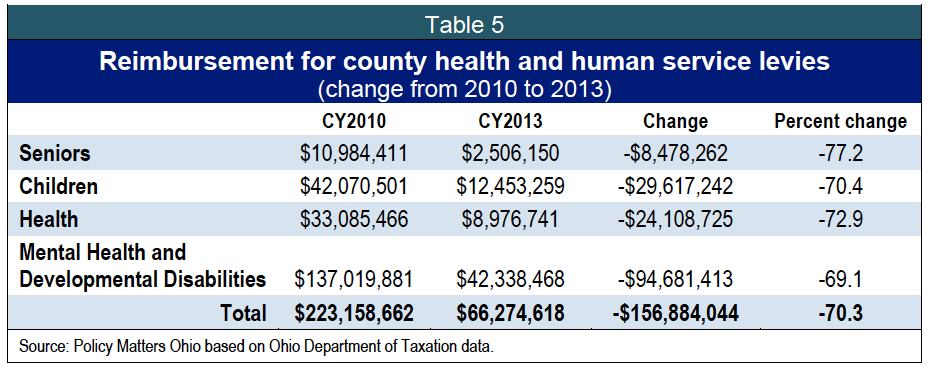

After the biennial state budget was approved last year, Franklin County reviewed its likely impact, and estimated the county would take a $13.4 million hit to its general fund in calendar year 2013 compared to its CY 2011 budget (Most of this was from cuts in the Local Government Fund, but $2 million from the accelerated phase-out of reimbursements for the tangible personal property tax and the public utility property tax reflected the difference with prior law, not the amount in the County’s 2011 budget).[23] As with many counties, Franklin County also is experiencing larger losses to the tax reimbursements that it had received for levies supporting specific services for the elderly, children, alcohol and drug addiction and mental health, and others. Cuts to these tax reimbursements compared to prior law, along with other program cuts in the state budget to Franklin County agencies, were expected to total another $28 million this year. So overall, the county figured the negative impact of the state budget in CY 2013 at more than $41 million. By contrast, based on Policy Matters’ revenue estimate, Franklin County would receive $10.5 million a year in casino gaming taxes. Table 5 shows how much tax reimbursements for local health and human service levies are being reduced state-wide between calendar 2010 and 2013.

The cuts in state tax reimbursements also affect other services supported by property-tax levies, such as local community colleges, emergency services and parks. Between calendar year 2010 and 2013, community colleges are scheduled to lose more than $12 million in such support, or all but $271,541 of the total; emergency services will lose $3.1 million or 64.7 percent of the total, and levies for local parks will lose $10.2 million or 75.6 percent.[24]

As noted above, the four cities that have or will soon have casinos receive revenue based on what that casino generates, and they and four other cities share half the revenue that goes to their counties. Table 6 reviews what predicted casino revenues will be in those eight cities, compared to estimated losses from the local government funds, tax reimbursements and the estate tax. All of these are approximations; data available on distributions to municipalities of local government funds do not allow for an exact comparison of future distributions (see data note, p. 13).

As officials from Columbus and Cleveland have noted recently,[25] casino gaming revenues come nowhere near making up the losses they are experiencing because of changes in state tax policy. The four casino host cities – Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus and Toledo – likely will receive less as a group in gaming tax revenue than their 2013 loss just in local government funds. Estate tax elimination alone is likely to offset all of Cincinnati’s casino tax gains, as well most of the proceeds that will go to Akron. Youngstown comes closest to breaking even, but it is still a loser, comparing casino taxes with lost tax revenue and tax reimbursements.

Policy Matters estimates City of Cleveland casino-gaming revenue at $16.3 million a year, while total losses from estate tax, Local Government Fund and tax reimbursements likely will amount to $32.6 million. This does not include reductions in state grants for programs. “It’s completely insufficient from what we lost,” said city Finance Director Sharon A. Dumas.

It will be some time before city finance officials can accurately peg all of the financial effects of the casinos. As The Plain Dealer has reported, revenues from Cleveland admission, car rental, hotel and parking taxes have increased; in June, revenue from those sources was up $1.2 million from a year earlier.[26] Income tax is also coming in higher than the budgeted amount, although Dumas notes that results less from the casino than from strong construction activity downtown.[27] The casino also has brought some additional costs, such as $2 million the city is spending this year for public safety outside the casino and nearly $600,000 for public services, such as keeping the area clean. Dumas wants to see how the casino does over a longer period of time, when business has settled to a regular level, to be able to give a full assessment of its financial effects on a long-term basis.

Cleveland has allocated 15 percent of its casino gaming revenue to city council members, with the other 85 percent going into the general fund for operations. The Columbus City Council recently approved putting most of its casino taxes into the city’s general fund.[28] Local governments are using casino revenues for different purposes – some are using it to make up cuts, others look to spend it for economic development, and some are still watching to see what regular revenue it will produce before making budget decisions .[29] School districts will only see their first payments next January.

Reshuffling tax revenue?

Besides the eight cities, Ohio’s other cities, as well as villages and townships, do not share directly in casino revenue. Together with the cuts that all local governments are experiencing from the changes in state tax policy, this has helped result in efforts to reshuffle state-aid revenue and direct some of it localities that don’t currently share in it.

Sen. Bill Seitz of Cincinnati has sponsored Senate Bill 364, which would overhaul the distribution formula for local government funds. The formula in the bill would reallocate some of the money now going to counties so that cities, villages, townships and other entities would receive a larger share. Seitz has cited an analysis by the County Commissioners Association of Ohio from last year, when an earlier version of his proposal was being considered as part of the state budget, that it would shift about $22 million statewide from the counties to the smaller municipalities.[30] While that may seem like a relatively small share of the total LGF state-wide, reductions in some small counties especially could be substantial.

In his description of the bill seeking cosponsors,[31] Seitz said the bill would establish a new “default” formula for determining how to share Local Government Funds that go to counties for distribution.[32] It is based on the formula that Franklin County has been using, guaranteeing counties a 30 percent share of the total allocation. Based on a sample of six counties that have run the numbers, the memo says, the new formula would benefit all townships, villages, small cities, park districts and big cities in them. “Most (but not all) counties will be adversely affected by this new formula,” it says. Seitz argues that counties will not suffer from the elimination of the estate tax as subdivisions will, that counties and the eight largest cities receive casino money, and that all 88 counties will receive more in casino money than they will lose under the bill’s new LGF distribution formula. Under earlier legislation approved by the General Assembly, county auditors will report to the state auditor by Nov. 1 on the formulas they use now, which will be used to analyze how the proposal in the bill would affect different units of government.

However, as the county commissioners association has noted,[33] counties as an agency of the state are responsible for a variety of state-mandated services, such as the public defender, the courts and elections. Like other local governments, counties also have been hit by reductions in other revenue sources, including investment income and property taxes. And Brad Cole, senior policy analyst at the association, notes that counties provide various services to townships; the county sheriff, who may do road patrols in the townships, in many counties is the only law enforcement official in a position to provide emergency response for residents in unincorporated areas.[34] As this report has detailed, counties receiving casino taxes will not be receiving anything like the revenue needed to replace the cuts they have received because of changes in state tax policy. While it is too soon to judge the exact fiscal effect on cities receiving casino gaming revenue, particularly casino host cities, it’s clear that their losses from these three sources far exceed the new revenue they are likely to get. A rejiggering of the funding among hard-pressed entities dances around the real issue: That the cuts have affected all local governments, and need to be restored. Rearranging the funding amounts to robbing Peter to pay Paul.

Video Lottery Terminals

At the same time as casinos are opening, so are video lottery terminals (VLTs) at Ohio race tracks. Scioto Downs in Columbus opened in June with 1,787 video lottery terminals. Like other “racinos,” as they are known, it receives a 66.5 percent commission, and the other 33.5 percent goes to the Ohio Lottery (so the tax rate is similar to the one for casinos).[35] In its first three months of operations, Scioto Downs generated an average of $4,023,332 a month in such revenue, though unlike the Cleveland and Toledo casinos, the amount increased slightly from month to month.[36] Five other tracks, including two that are moving their locations, have applied to the Ohio Lottery Commission for approval to operate as video lottery retailers, and the other track, Northfield Park, has announced that it, too, is looking to add VLTs.[37] If each generated the same ongoing revenue that Scioto Downs did in its first three months, the state would generate a total of $337.9 million in annual tax revenue. The lottery has estimated that a track with 1,500 VLT machines will generate around $3 million per month in tax revenue.[38] Using the lottery’s estimate, if each had 1,500 machines and generated $3 million a month, that would amount to $252 million a year. Some, of course, may operate more than that number of machines.

Unlike casino tax revenue, which is distributed through the formula described above to local governments, schools and others, new government revenue from the racetracks will go to the state (or to be exact, the lottery, where the revenue is treated like other lottery profits).[39] An attempt to challenge the racinos so far has failed in court, but an appeal is still pending.[40] If all the racinos open, this will depress casino revenue. For instance, as noted in Table 1, the budget and tax departments estimated in 2009 that the opening of 7 racinos would reduce the total annual amount of annual casino tax revenue from $643 million to $470 million.[41]

Revenue the lottery receives from the racino VLTs, like other lottery revenue, is required to be spent on education. The constitutional amendment authorizing the casinos also provided that,

Tax collection, and distributions to public school districts and local governments, under sections 6(C)(2) and (3), are intended to supplement, not supplant, any funding obligations of the state. Accordingly, all such distributions shall be disregarded for purposes of determining whether funding obligations imposed by other sections of this Constitution are met. [42]

However, just as Lottery revenue does not truly amount to a bonus for K-12 education over and above what the state would spend, there is little reason to believe that the casino revenue designated for schools and local governments will constitute permanent, extra revenue.

Regardless of the supplantation issue, casino revenues, while significant, go nowhere near making up for the cuts sustained by local governments from state tax policy changes made in the current state budget. The end of the estate tax, the slashing of the Local Government Fund, and the reduction in promised reimbursements for lost local tax revenue add up to far more than the new revenue that is likely to be generated. Ohio needs to boost its investment in schools, local governments and human services with additional revenue from those who can afford to pay. Revenue from gambling does not suffice.

A note on the data

Estimating cuts in state aid to local governments – in the Local Government Funds, the reimbursements for local property taxes that the state budget slashed and as a result of the repeal of estate tax – necessarily involved making certain assumptions.

In order to estimate the estate tax likely to be lost by municipalities and townships, we totaled the amount each type of local government had received in estate tax in 2007, 2008, 2009 and 2010, and averaged them to arrive at an annual average. See Ohio Department of Taxation, Tax Data Series http://tax.ohio.gov/divisions/tax_analysis/tax_data_series/estate/publications_tds_estate.stm. Other data available from the taxation department show somewhat different amounts of estate tax collections. Calendar year data for such collections is invariably lower than the fiscal year data presented in the department’s annual report (see http://tax.ohio.gov/divisions/communications/publications/annual_reports/2011_annual_report/estate_tax.pdf). The department does not have a definitive explanation for the differences, given the many parts and players in the process, but believes it may lie in the practice of counties withholding some distributions of unfinalized estates to their governmental units until such estates are finalized, so distributions totals are lower than the reported settlement totals.[43]

We arrived at Local Government Fund losses by learning the amounts of County Undivided LGF (CULGF) estimated by the Ohio Department of Taxation in Calendar Year 2013, available at http://tax.ohio.gov/channels/government/OhioDepartmentofTaxation.stm (see Forecasted Revenue CY 2013), and CY 2010, available at http://tax.ohio.gov/divisions/tax_analysis/tax_data_series/local_government_funds/publications_tds_local.stm (see County Undivided Local Government Funds - Amounts Distributed within Counties by County Budget Commissions by Subdivision or Subdivision Class). We used the latter data set to obtain the amount municipalities and townships receive in LGF. Based on the share that municipalities and townships had of 2010 distributions, we estimated their share of projected 2013 distributions. While there are some differences between the two sets of LGF data for how much each county received in 2010, these are not substantial and there is no more current data available than 2010 on the distribution of undivided LGF to municipalities and townships.

To estimate the amounts of Local Government Funds received by the eight cities, we used CY 2010 data on such amounts of the county undivided LGF from the taxation department, and applied the proportion each city received of the 2010 total to the 2013 estimate for the CULGF by the taxation department. This assumes that the undivided LGF is divvied up the same way in both years.

Some additional Local Government Funds are distributed directly to municipalities (Municipal direct allocations). We added these amounts, for both all municipalities and separately for the eight cities, using taxation department data available at http://tax.ohio.gov/channels/government/revenuesharing.stm (see Direct LGF Distributions to Qualifying Municipalities, Pursuant to Enacted FY 12-13 Budget). While the tax department is required to come up with a calendar year forecast of the CULGF, it is not required to do so for the Municipal Direct distributions. We used second-half 2012 data for the second half of 2013 as a proxy, since we do not know what the distribution will be under the new formula in the next budget (the formula reverts from a set percentage to a share of revenues again and revenue forecasts for the next budget period are not available.)

LGF totals include the Dealers in Intangibles Tax (DIT). As part of the current state budget, all of the DIT that had gone to local governments goes to the state starting June 30, 2012.

The taxation department provided us with spreadsheets showing reimbursement payments for public utility property tax and tangible personal property tax provided to each jurisdiction for each levy in calendar year 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013 (estimated). We used these to arrive at forecasts for the total reductions for different units of local government, as well as for different types of levies (e.g. health and human services, community colleges, etc.).

[1] Coolidge, Alexander, “Casino tax-revenue projections on decline,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, June 1, 2012. Tax revenue is expected to be considerably lower than the $651 million a year projected by the Innovation Group in a 2009 study paid for by the sponsors of the ballot initiative that established the right of the casinos to operate in Ohio. This estimate did not take into account the likely addition of slot machines, or video lottery terminals, at Ohio racetracks. The constitutional amendment allows casino operators to have up to 5,000 slot machines in each casino, a figure that none of the four will approach in the immediate future. The state did take into account the possibility of VLTs in 2009, with consequently much lower revenue estimates. (See Table 1.)

[2] Office of Budget and Management and Ohio Department of Taxation, Re: State Issue 3: Casino Ballot Initiative, Oct. 2, 2009, Analysis of 2009 Ohio Casino Initiative, available at http://1.usa.gov/STnWxU. This report reviewed possible casino reviews both with and without the existence of seven racetrack casinos.

[3] Sobul, Mike, “Will Revenues from Casinos Fill Holes in School Budgets?”, Public Finance Resources Inc., revised May 29, 2012, available at http://www.pfrcfo.com/pdf/Casino%20Article%20(Revised%20May%2029,%202012).pdf

[4] Rock Gaming, which operates Horseshoe Casino Cleveland and will open a facility in Cincinnati, estimated that each would generate $100 million in gaming revenue a year, which works out to gross revenue of $303 million a year. See Rock Gaming fact sheets, Horseshoe Casino Cleveland, May 2012, and Horseshoe Casino Cincinnati, September 2012, available at http://www.rock-gaming.com/fact-sheets/. Penn National, operator of Hollywood Casino Toledo, estimated when it opened in the casino in May that it would produce gross revenue of $195 million a year (conversation with Bob Tenenbaum, Penn National spokesperson, Sept. 7, 2012).

[5] Ohio Casino Control Commission, Monthly Casino Revenue, available at http://1.usa.gov/Ux1WKU.

Penn National has not provided a current estimate for anticipated Columbus casino revenue.

[6] Conversation with Rick Anthony, Sept. 13, 2012

[7] Other projections have been made, including the Innovation Group’s estimate before the casino issue went on the ballot in 2009, and Moelis & Co., which was employed by the state as part of negotiations with the casinos and racetracks. Moelis made projections in June 15, 2011, that work out to overall tax revenue of $477.1 million a year, a downward revision from its 2009 estimate.

[8] Cuyahoga County Fiscal Office, “Ohio Casino Tax Overview,” June 12, 2012, available at at http://council.cuyahogacounty.us/pdf_council/en-US/Casino/OhioCasinoTaxOverview-062012.pdf

[9] Ohio Casino Control Commission, Monthly Casino Revenue, available at http://1.usa.gov/Ux1WKU.

[10] Ohio Department of Taxation, Distribution - Casino Tax, available at http://1.usa.gov/SF23HQ. School districts have not yet received funds; their first distribution will come next January.

[11] Patton, Wendy, “We Deserve a Better Business Plan: An Assessment of Ohio’s New Biennial Budget,” Policy Matters Ohio, Aug. 1, 2011, available at http://bit.ly/V1Dvby.

[12] Ibid, p. 2

[13] Sobul, Mike, Public Finance Resources Inc., “Will Revenues from Casinos Fill Holes in School Budgets?” Revised May 29, 2012, available at http://www.pfrcfo.com/pdf/Casino%20Article%20(Revised%20May%2029,%202012).pdf

[14] Sobul’s estimates are based on no other VLT facility but Scioto Downs opening by Jan. 1, 2015, and that the second phase of the Cleveland casino has not opened. Overall, they are somewhat higher than the estimates in this report, though we have used his estimate for the Columbus casino. Sobul adjusted the Columbus revenue downward from the original taxation department projection by 30 percent because of the opening of the Scioto Downs VLT facility.

[15] Budget in detail, House Bill 153, 129th General Assembly, Main Operating Budget Bill, FY 2012 – FY 2013, (with FY 2012 actual expenditures and FY 2013 adjusted appropriations) Legislative Service Commission, August 7, 2012

[16] Wendy Patton, “A Thousand Blows: State Budget Cuts Funding for a Swath of Public Services,” Policy Matters Ohio, August 2001; also based on updated spreadsheets provided by Ohio Department of Taxation as well as data on the Ohio Department of Taxation website.

[17] Ohio Department of Taxation, 2011 Annual Report, Page 53, available at http://1.usa.gov/VPMUSV. Other amounts used in this report for local-government estate-tax losses are based on the average amount between calendar years 2007 and 2010, which was less than the FY 2011 amount.

[18] Estate-tax losses, which are not included in this number, won’t begin till later in calendar 2013. Casino revenues also will not reach their full amounts till later in the year, as the Cincinnati casino is set to open in the spring.

[19] Policy Matters Ohio calculations from Ohio Department of Taxation, Tax Data Series, Estate Tax, available at http://1.usa.gov/QrS72I. These numbers may well understate the total revenue lost, since other data from the taxation department pegs the amount of estate tax somewhat higher. See data note, p. 13.

[20] This reports reviews LGF and tax-reimbursement losses during calendar year 2013, and annual estate-tax losses based on the 2007-2010 average. As noted, neither estate-tax losses nor total casino revenues will hit the full annual estimates used here till after the end of calendar 2013.

[21] Cuyahoga County Executive Fiscal Office, Office of Budget & Management, “Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Second Quarter Report,” p. I-17

[22] As noted, Cuyahoga County has projected somewhat lower casino-tax revenue, using lower estimates for the gross revenues that the Columbus and Toledo casinos will bring in. It has estimated $9.7 million in 2014 revenue for the county in one estimate, and $8.8 million in another, less optimistic scenario. See Cuyahoga County Fiscal Office, Ohio Casino Tax Overview, June 12, 2012, available at http://bit.ly/QzhQpI.

[23] Franklin County Office of Management and Budget, OPERATING BUDGET (HB 153) - ESTIMATED IMPACT ON FRANKLIN COUNTY, July 26, 2011. Assumes appropriation levels in HB 153 continue throughout CY 2013; Amounts subject to revision pending the continued review of the provisions of HB 153

[24] Based on calculations from data provided by the Ohio Department of Taxation; received 8/30/2012 and 9/12/2012.

[25] The Columbus Dispatch reported Sept. 8: “(Columbus Mayor Michael) Coleman, City Auditor Hugh Dorrian and Council President Andrew J. Ginther all agree that no matter how much revenue comes in, it won’t be a jackpot for the city. “The weight of the state’s cuts really hit hard in 2013, so anyone who thinks that casino revenues are going to create a windfall for the city is mistaken,” said Dan Williamson, Coleman’s spokesman. “Those cuts are deep, and they are significant.”” Lucas Sullivan, “City’s Casino Take Will Pay for State Cuts, Arena,” The Columbus Dispatch, Sept. 8, 2012, available at http://bit.ly/PIMzim. Officials elsewhere also have voiced this point: Carol McFall, chief deputy auditor of Mahoning County, told the Youngstown Vindicator: “Although I appreciate the casino money, and we need every dollar we can get, it’s not covering what we’re losing.” Peter H. Milliken, “Valley Ponders Casino Windfalls,” The Vindicator, Aug. 5, 2012, available at http://www.vindy.com/news/2012/aug/05/valley-leaders-ponder-casino-windfalls/

[26] Ott, Thomas, “Casino boosts hotels, parking, tax spike shows,” The Plain Dealer, 5, 2012. Not all of this is necessarily casino-related, but it suggests that there should be some ancillary revenues for casino cities.

[27] Conversation with Sharon A. Dumas, director, department of finance, City of Cleveland, Sept. 13, 2012.

[28] Sullivan, Lucas, “City’s Casino Take Will Pay for State Cuts, Arena,” The Columbus Dispatch, Sept. 8, 2012, and

[29] McLaughlin, Sheila and Angela Travillian, “Casinos’ jackpot a long shot, at first,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, June 1, 2012.

[30] Gokavi, Mark and Matt Sanctis, “Proposal would change $22 million in state funding,” The Dayton Daily News, posted Sept. 15, 2012, available at http://bit.ly/VPNJLn. See “Estimated LGF Loss to Counties – Proposed New “Default” Statutory Formula – HB 153,” County Commissioners Association of Ohio.

[31] Sen. Bill Seitz, Memorandum to all Senate members, Re: Co-Sponsor Request: LGF – Reallocation Formula, July 10, 2012.

[32] It also requires that three-quarters of the subdivisions within a county approve any alternative formula, eliminating the requirement that the board of county commissioners and the legislative authority of the largest city in the county approve any alternative formula. However, it also provides that an alternative formula can’t result in fewer dollars going to either the county or the largest city than the new statutory formula would produce, unless each approves.

[33] County Commissioners Association of Ohio, Statehouse Report, “More info on Seitz LGF formula proposal,” June 1, 2012. CCAO figures that about 77 of Ohio’s 88 counties could lose money under the approach proposed in the bill.

[34] Conversation with Brad Cole, Sept. 24, 2012

[35] A small portion of the racetracks’ commission goes to others, such as the 0.5 percent that goes for gambling and other addiction-related services. As part of VLT legislation, the General Assembly also approved small appropriations for communities that house racinos, except Columbus, and also for the two that will be losing tracks because they relocate.

[36] Ohio Lottery Commission, VLT Fiscal Revenue Report, available at http://bit.ly/RlzFZj. The racino added 301 VLTs after its opening, so it had 2,088 in August, which helps account for the increase.

[37] Ott, Thomas, “Hard Rock, Northfield Park announce racino plans,” The Plain Dealer, April 19, 2012, available at http://www.cleveland.com/metro/index.ssf/2012/04/hard_rock_northfield_park_unve.html.

[38] Conversation with Danielle Frizzi-Babb, deputy director of communications, Ohio Lottery, Aug. 30, 2012.

[40] LaMarra, Tom, “Group Appeals Latest Ruling in Ohio VLT Case,” BloodHorse.com, Sept. 1, 2012, available at http://www.bloodhorse.com/horse-racing/articles/72491/group-appeals-latest-ruling-in-ohio-vlt-case.

[41] Op. cit., Office of Budget and Management and Ohio Department of Taxation, Re: State Issue 3: Casino Ballot Initiative, Oct. 2, 2009, Analysis of 2009 Ohio Casino Initiative

[42] Ohio Constitution, Article 15.06(C)(3)(g), http://www.legislature.state.oh.us/constitution.cfm?Part=15&Section=06.

[43] Email from Gary Gudmundson, Ohio Department of Taxation, Sept. 19, 2012

Tags

2012Revenue & BudgetTax ExpendituresTax PolicyWendy PattonZach SchillerPhoto Gallery

1 of 22