GED collapse prevents Ohioans from attaining high school diplomas

February 18, 2016

GED collapse prevents Ohioans from attaining high school diplomas

February 18, 2016

Contact: Hannah Halbert, 614.221.4505

Executive summary

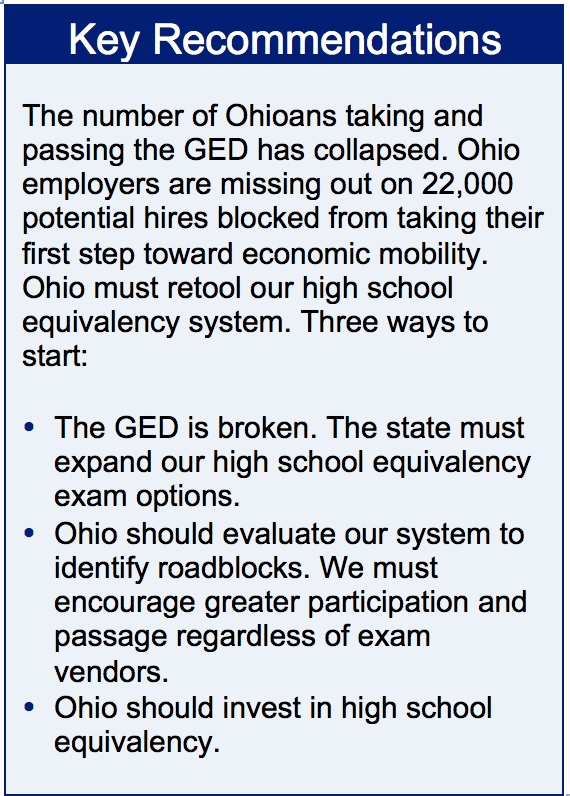

The number of people attempting and passing the GED has plummeted. The Ohio economy is tough on low-wage workers with limited formal education. Without a high school diploma, it is virtually impossible to get a family-supporting job. But the GED has become a barricade, blocking Ohio workers from career goals, instead of a launching pad.

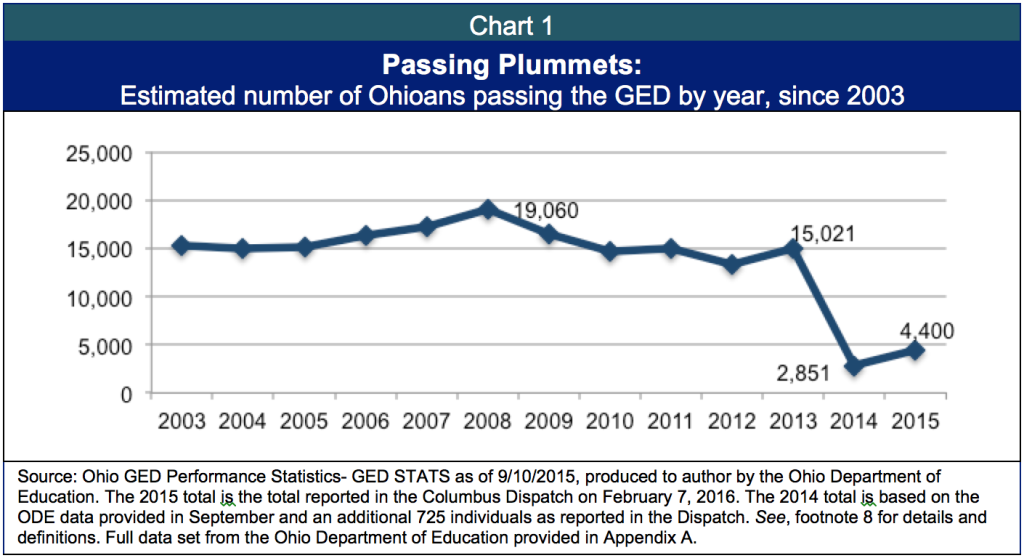

The number of people attempting and passing the GED has plummeted. The Ohio economy is tough on low-wage workers with limited formal education. Without a high school diploma, it is virtually impossible to get a family-supporting job. But the GED has become a barricade, blocking Ohio workers from career goals, instead of a launching pad.The GED – the copyrighted brand name of the test Ohio uses to award high school equivalency diplomas – fundamentally changed when PearsonVUE, the world’s largest private, for-profit education corporation, took over the test. After Pearson changes were implemented, the number of Ohioans passing the test plunged by 85 percent, from more than 14,800 a year on average between 2009 and 2013 to fewer than 2,200 in 2014. So few passed the GED, the scoring system was changed. We estimate that 7,251 people have now passed the GED in the two years since the changes were implemented. This is cold comfort given that more than 15,000 Ohioans passed the test in the year prior to the testing changes. As a result, there are about 22,000 fewer Ohioans with an equivalency degree than we would have had if we had kept pace. That’s 22,000 workers blocked from a good career ladder, and 22,000 potential hires that Ohio employers are missing out on.

The changes Pearson made include tripling the cost of the test from $40 to $120, requiring test-takers to use a computer, testing more analytical and complex skills, and requiring online registration with an email address and a credit card. In a perverse way, the changes create huge barriers for the very population that needs a high school equivalency. About 48 percent of Ohioans without a diploma have either no computer or no Internet service. Many also lack a bank account or credit card. Median earnings for the 795,664 working-age Ohioans without a high school degree were $20,122 in 2014, about $15,000 less than for the population as a whole. Now, to increase their income and afford the Internet, they must pass an expensive, computerized test. Recommendations for Ohio:

- Add more alternate testing options as 21 states have done.

- Reinvest in high school equivalency instead of cutting funding.

- Evaluate the system and get back on track, regardless of the testing product.

Introduction

The number of Ohioans who pass the high school equivalency exam has plummeted since PearsonVUE, the world’s largest private for-profit education corporation, took over testing, tripled the cost, changed the test and created other barriers.[1] The system is completely broken, preventing thousands of Ohioans from testing and attaining diplomas. Ohio must fix it to help families succeed and help employers find qualified workers.After the Pearson changes were implemented, the number of Ohioans passing the GED – the copyrighted brand name of the test – plunged by 85 percent, from more than 14,800 a year on average between 2009 and 2013 to fewer than 2,200 in 2014. A recent change in GED scoring increased the total number of Ohioans who passed the GED over the last two years by 1,425. Even with this change, we estimate that there are about 22,000 fewer Ohioans with an equivalency degree than we would have had if we had kept pace.

The changes Pearson made include tripling the cost of the test from $40 to $120, requiring test-takers to use a computer, testing more analytical and complex skills, and requiring online registration with an email address and a credit card. In a perverse way, the changes create huge barriers for the very population that needs a high school equivalency.

The Ohio economy is tough on workers with limited formal education. Without a high school diploma, it is virtually impossible to start a career or obtain a family-sustaining wage. Employers look to high school credentials to show that an applicant understands basic educational concepts, but also that the candidate has the diligence to complete a degree or an equivalency program. For good or ill, credentials matter – either as a signifier of mastery over a subject or as a proxy for competence in workplace behaviors.

The Cleveland Scene and the Pacific Standard have profiled Ohioans struggling to pass the GED to take the next step on their career path to become welders and nurses.[2] The profiled workers are experienced, they show up and get their jobs done (demonstrating just the sort of “soft skills” employers often say are needed). But because they cannot pass the GED they cannot gain traction in their careers and employers miss out on potentially great hires. For those Ohioans, and many like them, the GED has become a barricade, blocking them from their career goals, instead of a launching pad.

The Cleveland Scene and the Pacific Standard have profiled Ohioans struggling to pass the GED to take the next step on their career path to become welders and nurses.[2] The profiled workers are experienced, they show up and get their jobs done (demonstrating just the sort of “soft skills” employers often say are needed). But because they cannot pass the GED they cannot gain traction in their careers and employers miss out on potentially great hires. For those Ohioans, and many like them, the GED has become a barricade, blocking them from their career goals, instead of a launching pad.

To address the GED collapse, Ohio must fully evaluate its high school equivalency policies. Alternative tests are available and gaining in acceptance. High school equivalency means that the person has the same level of academic skill as someone with a high school diploma Twenty-one states now offer alternatives to the GED or are in the process of implementing alternatives. Ohio has alternative diploma pathways, but the programs are new, not for everyone, and small compared to the need.

Ohio’s testing system is fragmented and not transparent. We requested detailed data on the GED from the Ohio Department of Education in February of 2014.[3] After many requests, the department provided the data included in Appendix A in September 2015. Information on the state’s GED reimbursement voucher program was only provided to the author the day prior to publication. The two state agencies involved with the GED and adult basic education, the Ohio Department of Education and the Ohio Department of Higher Education, appear to be working relatively independently. The education department can access the GED data, which is managed by GED Testing Services.[4] The department of higher education administers the programs that help Ohioans prepare for the GED, but because it is not the administrator of the GED, it has access to the GED Testing Services only through the education department. This lack of public data transparency and the apparent absence of cross-agency communication make deep recommendations impossible. Calling for a study committee is often the death knell for policy change but here it is exactly what is needed. The state needs to make a concerted effort to dig deep in the data, bring cohesion across programs, and fill the gap left by the GED. The GED is broken. Ohioans deserve better.

Astounding drop in number of Ohioans taking, completing, and passing the GED

Ohioans are making education gains. In 2014, the share of Ohioans aged 25 and over with at least a high school education was 89.4 percent, up 1.3 percentage points in just four years.[5] This means about 222,500 more Ohioans had a high school education in 2014 than in 2010. Similar gains have been made in higher education, with more than 190,755 more Ohioans holding at least a bachelor’s degree in 2014 than in 2010.[6] Despite these gains, Ohio still ranks in the middle of the pack, 25th among states, for the share of adults who have completed high school or high school equivalency.[7] The GED test is a second chance for these adults to secure a high school credential.

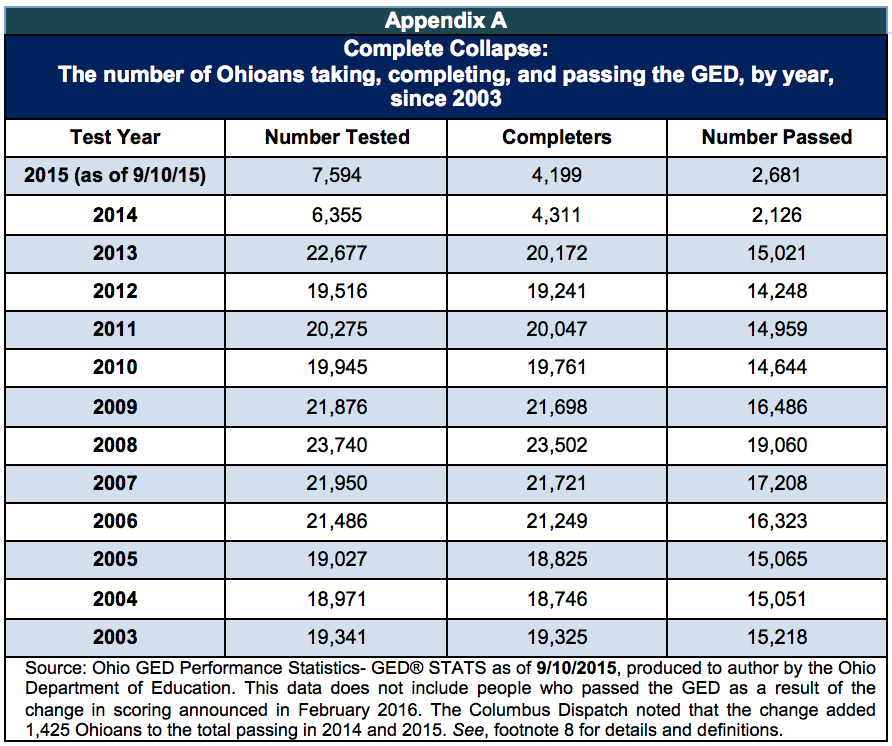

The number of Ohioans passing the GED and the number attempting the test has undeniably collapsed. In 2014, the year following the GED changes, only 2,126 people passed the test.[8] This is an 85 percent decline from the prior five years’ average.[9] This drop is similar to the national declines, which The Washington Post has called “astounding.”[10]

This month, in response to these abysmal statistics and likely in response to an increasing number of states abandoning the product as the sole high school equivalency exam, GED lowered the score needed to pass from 150 to 145 and added additional performance levels.[11] While the GED Testing Service has stated that this change is effective immediately in Ohio, the Department of Education states that it is not effective until March 1st. Regardless, this change has added to the number of people who have passed the GED. According to The Columbus Dispatch, this means an additional 1,425 Ohioans who took the GED over the past two years will now receive their degree.[12] The Department of Education will recalculate the totals after March, but based on the Dispatch article and the totals provided by the department of education, we estimate that 7,251 people have now passed the GED in the two years since the changes were implemented. This is cold comfort given that more than 15,000 Ohioans passed the test in the year prior to the testing changes. Even with the scoring change and the full year estimate provided in the Dispatch for 2015, the number passing the GED is down more than 70 percent from the state’s pre-2014, five-year average. Chart 1 shows the estimated number passing the GED based on data from the state education department and that reported in The Columbus Dispatch.

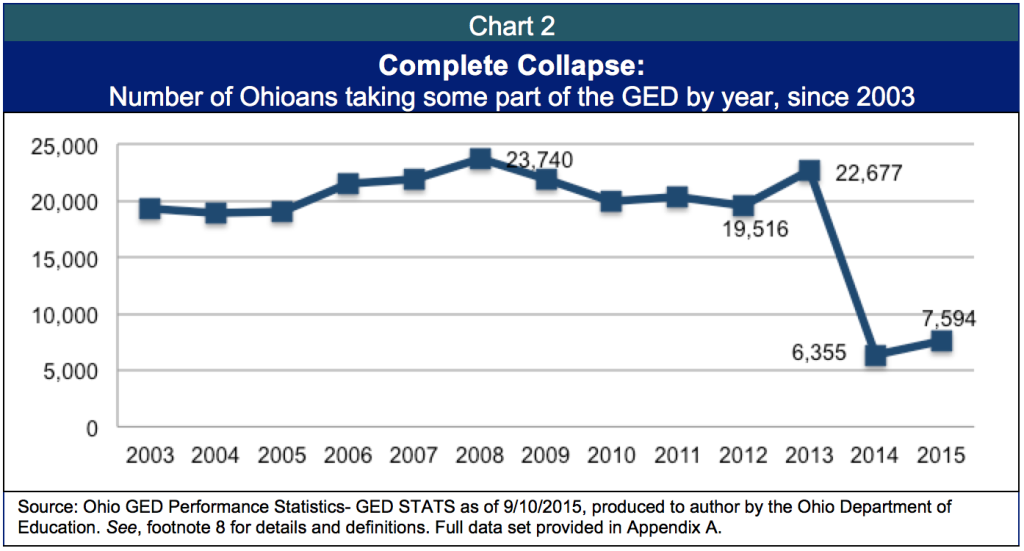

The GED has several testing sections that can be taken separately. In addition to the number passing the test, the number attempting “some of the test” has also collapsed. Between 2009 and 2013, an average of 20,858 Ohio “test takers” took at least one part of the GED. In 2014, only 6,355 Ohioans attempted some portion of the exam, a decline of nearly 70 percent.[13] Changes to the GED are chilling access and participation. More Ohioans had taken at least part of the test in 2015 than in 2014, rising to 7,594 by September 2015. Even with that improvement the number attempting the GED is still down more than 63 percent from the state’s five-year average. This is a problem that is not addressed by lowering the passing score. Ohio is nowhere near recovery. Chart 2 shows these considerable changes.

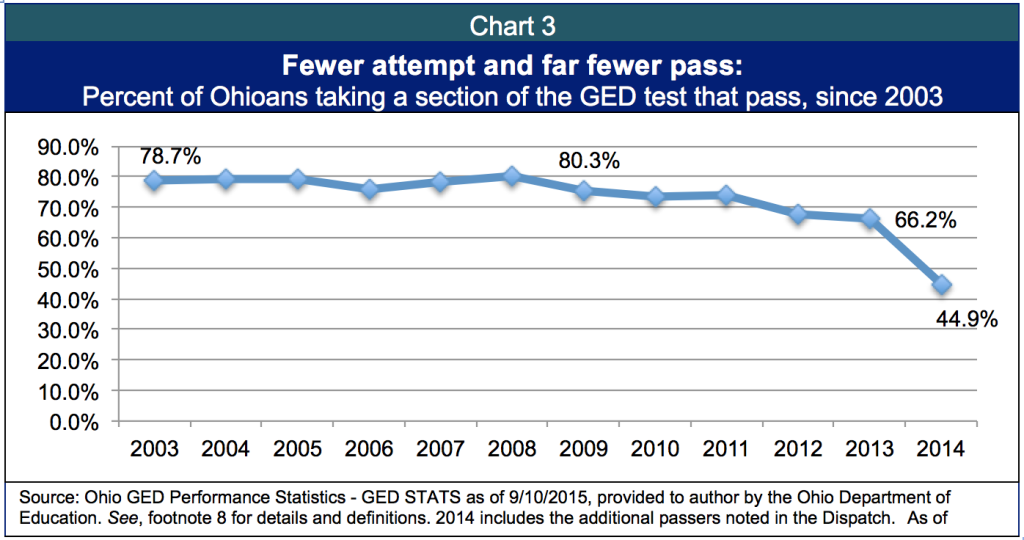

The share of attempters compared to passers remained high and relatively stable in 2003, the year following the last test update. The people behind the test predicted a similar return to normalcy after the 2014 changes, a prediction that has not panned out.[14] The pass rate, the number that take the GED in the year compared to the number that pass, remains abysmal. Chart 3 shows this decline.

The GED is hardwired into state law and practice. It is so ingrained that the high school equivalency diploma in Ohio is simply known by the trademark name GED. But the test has changed and the data suggests that Ohio no longer has a functional high school equivalency test. There are about 22,000 fewer Ohioans with an equivalency degree than we would have had if we had kept pace with prior years.[15] Ohio employers are missing out on 22,000 potential hires and 22,000 workers are blocked from taking their first step toward economic mobility. The drastic decline in the number taking and passing the test has far reaching consequences that should be evaluated by the state.[16]

What changed?

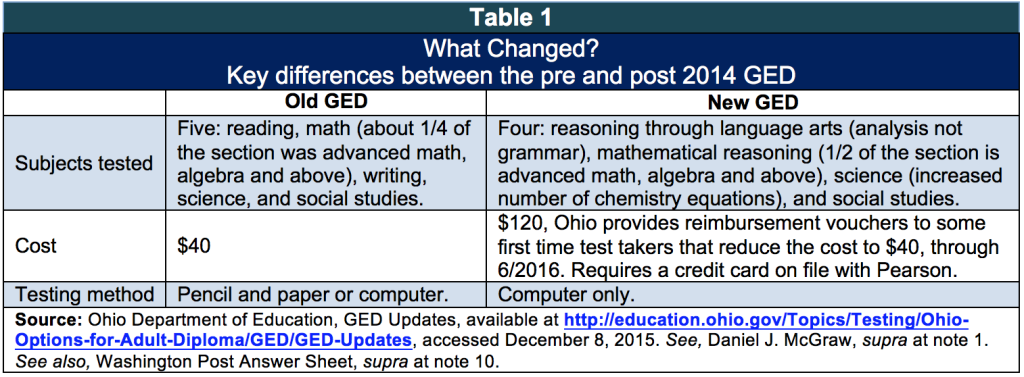

The GED was created in 1942 by the American Council on Education, a national higher education association representing presidents of accredited degree-granting institutions. The test was a way for World War II veterans who left high school for service to obtain a credential so they could enter college. As the labor market and higher education changed, so did the GED. The council on education updated the test in 1978, 1988, and 2002. In 2009, it could not cover the costs of another update, so the GED was privatized and turned into a for-profit venture. The council on education partnered with the for-profit publishing and testing company, PearsonVUE, the largest education corporation in the world.[17] Pearson initiated a series of changes to the test, which were implemented in 2014; the same year GED stats plummeted. Table 1 describes the key changes.

One of the more controversial changes made by Pearson was to align the test content with Common Core standards, without a phase-in period. This means the GED tests complex learning, like critical thinking, problem solving, and analytical skills rather than evaluating understanding of key concepts in core subjects. Many have said the GED is now too difficult and is testing the wrong skills for the primarily workforce-focused credential.[18] Other testing alternatives also are Common Core-aligned but are phasing in the new standards, allowing preparatory systems to keep pace.

The content change is only one of many changes that make preparing for and taking the GED more burdensome. The test is only administered in select sites and only by computer. The testing locations are different than the instruction site, creating additional stress. The test is more expensive. Registration is now online and requires an email address and a credit card. The official practice test is also online and the test can only be taken on a computer.[19] These differences may seem inconsequential but to a low-income adult these factors pile up. The increase in cost combined with the prospect of failing and needing to retake sections multiple times could easily tip the balance against attempting this credential.[20]

Some assume that the whole world is perpetually wired into the Internet and that everyone has an email address and credit card. But that ignores the reality of how many people without a high school education live. Census data shows that about 47.9 percent of Ohioans without a high school diploma or equivalent have no Internet service or no computer at all.[21] The FDIC estimates that about 50.9 million American adults don't have bank accounts, meaning that they have to resort to alternative financial services like payday lenders to obtain services like credit.[22] In a perverse way, these barriers are the very same conditions people are trying to overcome by obtaining their GED. Many low-income Ohioans without a high school degree lack computer access and skills. Now, to get into a technical program that would help them obtain those skills and increase their income, they must pass a relatively expensive, computerized test.

It is not clear if one particular change is driving down the GED numbers or if it is simply the sum of the changes that is responsible. The limited data provided by the Ohio Department of Education prevents adequate analysis. What is clear is that too few people are taking the test and too few are passing, meaning fewer Ohioans will be able to gain a foothold in the labor market.

Attaining a high school credential matters, current approach blocks the path

Those without a high school education are often stuck in low-wage, part-time, or contingent work. These jobs can keep people trapped in poverty, with the health, education and other challenges that come with destitution. We need better jobs in Ohio and we need a variety of tools to generate them, but one important component is investing in an educated workforce. Doing so can attract better employers, spur innovation, and generate returns in productivity and wages.[23]

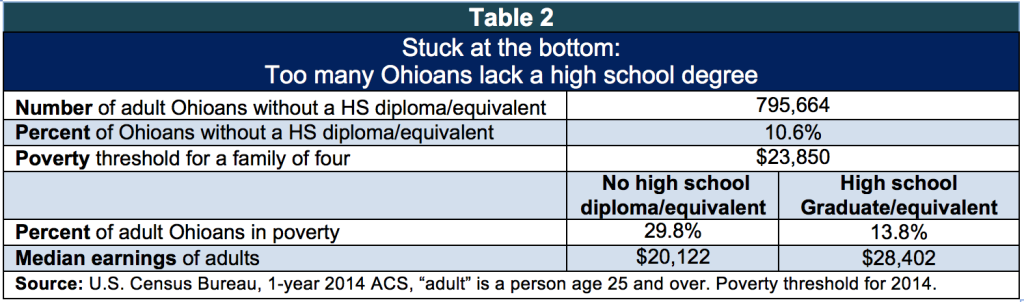

While the number of Ohioans without a high school diploma is shrinking, it’s still too high. For this simple reason, the drop in GED takers and passers, should trouble any policymaker seeking to grow Ohio’s economy. More than 795,664 working-aged Ohioans do not have a high school degree.[24] Nearly one-third (29.8 percent) of them lived in poverty in 2014. Data from the Working Poor Families project shows that nearly 70 percent of low-income families earning less than 200 percent of poverty are working.[25] Earnings are just very low. Median earnings for Ohioans age 25 and over without a high school degree were $20,122 in 2014, about $8,000 less than a high school graduate and $15,000 less than the population as a whole.[26] Table 2 shows some of these figures.

Workers of color are more likely to be stuck without a diploma: 16 percent for working-age, African-Americans, and 27.8 percent for Hispanics or Latinos.[27] Poverty and lack of this credential are also closely bound. Increasing diploma attainment and acknowledging the racial disparity in access to education is a necessary first step in addressing poverty, structural barriers to advancement, and implicit bias. Evaluating the GED data along race, sex, and geographic cleavages could identify specific community-based obstacles and best practices alike.

Why do people take the GED?

There are many reasons that students don’t complete their high school education and need to get their high school equivalency diploma. Some are doing so as a first step toward college or community college. This group might be well served by a test, like the new GED, designed to encourage computer use and test critical thinking, problem solving and other skills needed in higher education. Others just want a diploma so they can work. They may need it to move up at their job, keep their job, or find a new job. A test designed to measure success at post-secondary school may not be the right yardstick.

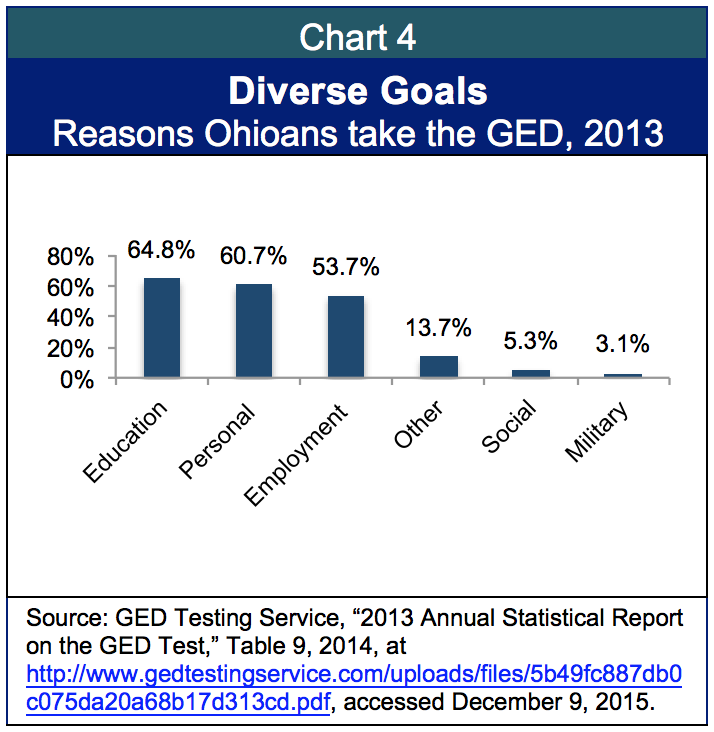

According to data from GED Testing Service, Ohio test takers cited education (64.8 percent), personal (such as being a role model or for personal satisfaction, 60.7 percent), and employment (53.7 percent) as their motivation for taking the test. Chart 4 details these causes.

According to data from GED Testing Service, Ohio test takers cited education (64.8 percent), personal (such as being a role model or for personal satisfaction, 60.7 percent), and employment (53.7 percent) as their motivation for taking the test. Chart 4 details these causes.

Even among those selecting education and employment reasons, goals were varied and suggest that different methods of credentialing might be appropriate. Most respondents who selected education were taking the test to enter a two-year program (37.6). Another 19.6 percent hoped to go to technical or trade school. Among those motivated by employment, 44.5 percent were seeking a better job, more than 8 percent were trying to get a first job, and 11.9 percent were trying to keep a job or fulfill a job requirement. “Social reasons” include court orders (4.1 percent) and requirement by a public assistance program (0.8 percent).[28]

Those looking for a post-secondary education may be better served by the new standards. Those seeking to retain employment, get a first job, or comply with a court order may be better served by a test that will help them document mastery of basic concepts and commitment to work. They need a test that will motivate them to take additional steps toward building their skills, rather than one that closes pathways. The diversity of goals suggests the need for a variety of testing options, but fundamentally the gateway test should expand options, not close them.

High school equivalency alternatives in Ohio

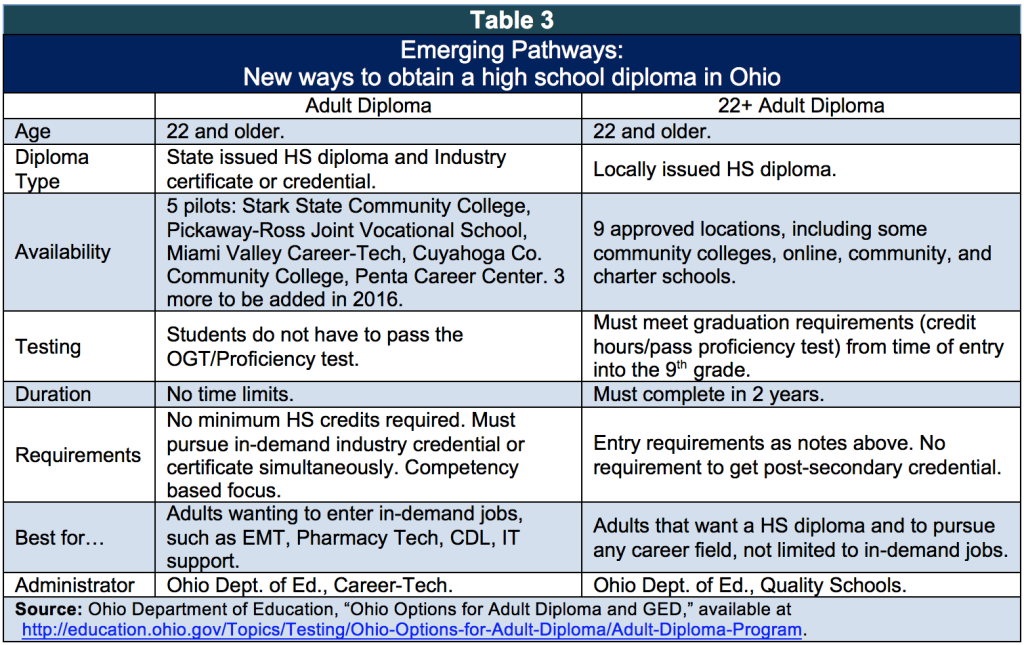

The Ohio Department of Education is creating additional alternative paths to a high school degree for adults. The new pathways incorporate integrated learning strategies that have shown promising completion rates. These programs may be valuable additions to Ohio’s education toolbox but none can replace the straightforward path to an equivalence degree that was once offered by the GED. They are new, only now being implemented, small, and not necessarily options for everyone who needs a high school credential. Table 3 details the new programs for adults.

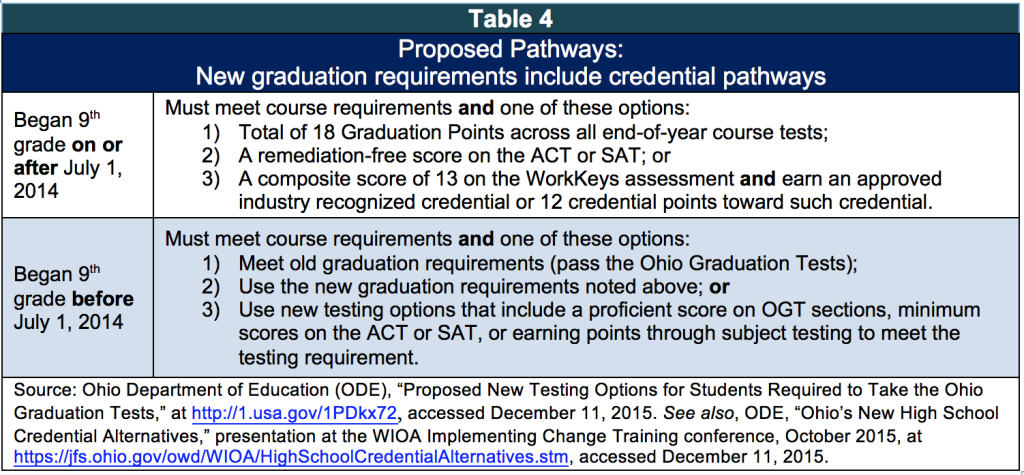

Those under 18 who are disconnected from school and work may have to find new ways to obtain a GED as the state no longer permits 16- and 17-year olds to take the GED unless they meet a series of exceptions.[29] For younger Ohioans who did not complete high school, Ohio has dropout recovery programs. The state has also created new graduation requirements that include vocational credential pathways.[30] These options are only now being finalized and implemented across Ohio. Table 4 details the new graduation options that might also extend to some adult learners.

More states are choosing GED Testing Alternatives

It is too early to determine the impact of Ohio’s new high school equivalency alternatives. What is clear is that these initiatives are geared toward a specific set of learners: those seeking a post-secondary credential beyond their equivalency diploma. These options will not replace the GED test, but may prove to be good supplements. Ohio must maintain a test that is accessible and available to those not seeking additional credentials. Other states faced with the changes to the GED and deteriorating pass rates have sought out alternative tests to the GED.

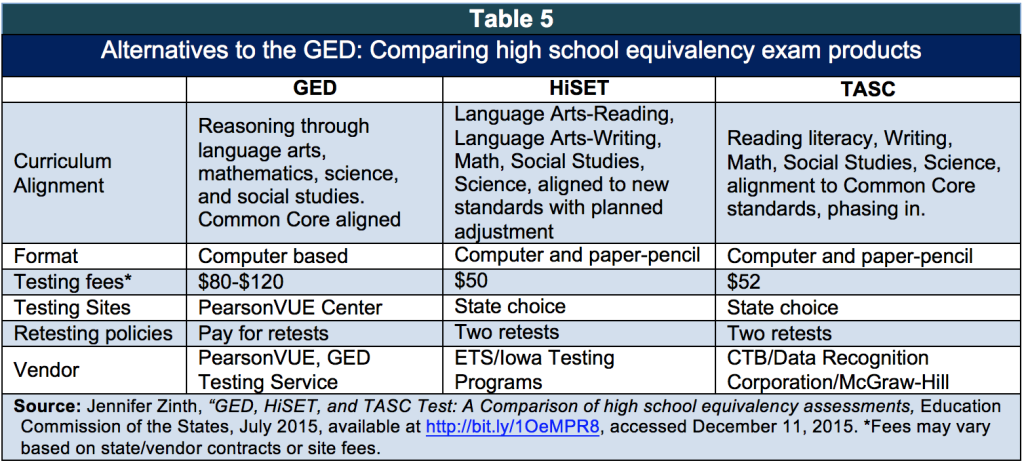

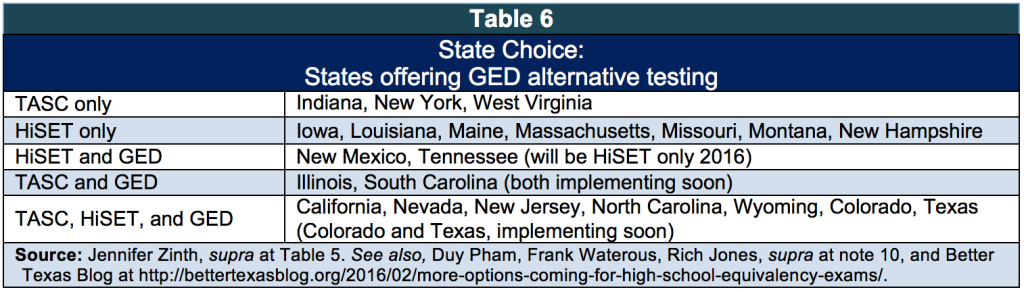

Two alternative testing products are available in some states, but not yet offered in Ohio: the HiSET (High School Equivalency Test), from Educational Testing Service and the Iowa Testing Program; and the TASC (Test Assessing Secondary Completion) from the CTB/McGraw-Hill. Table 5 compares these to the GED.

Currently, 21 states offer alternatives to the GED or will soon do so, and 10 of those have eliminated the GED. Texas and Colorado, the most recent states to expand high school equivalency testing options are permitting students to take any of the three equivalency exams, giving adults and out-of school youth multiple options and formats to obtain their degree. Virginia has also started evaluating alternatives. Table 6 details these changes.

According to the Center on Law and Social Policy, the most common reasons states have switched were:

- To offer a lower price than the GED fee, so the test remained affordable,

- To offer a paper-pencil option,

- To avoid contracting with a for-profit vendor for equivalency testing.[31]

Increasing services, prep and support

Ohio should also evaluate how well the state supports GED preparation. Many of Ohio’s GED preparation services flow through the Adult Basic Literacy Education Network (ABLE) and the state Career-Tech Centers. These programs are administered by different state agencies. ABLE is overseen by the Ohio Department of Higher Education, while Career-Tech is administered through the Ohio Department of Education. They have different primary service populations and goals. Ohio’s ABLE network provides free education and training to adults who need to improve basic literacy, math, and life skills to be successful in post-secondary education. ABLE is available in every Ohio county. The Department of Higher Education must rely on the education department, the formal administrator of the test, to access GED data.

Career-Tech is Ohio’s vocational education system. Generally, Career-Tech focuses on high school juniors and seniors enrolled in vocational programs like construction, health, and engineering. It has been expanded to enroll students as young as seventh grade in career programs and is increasingly serving adults. Career-Tech administers Ohio’s Adult Diploma Program and is a required stop to receive an Ohio GED reimbursement voucher.[32]

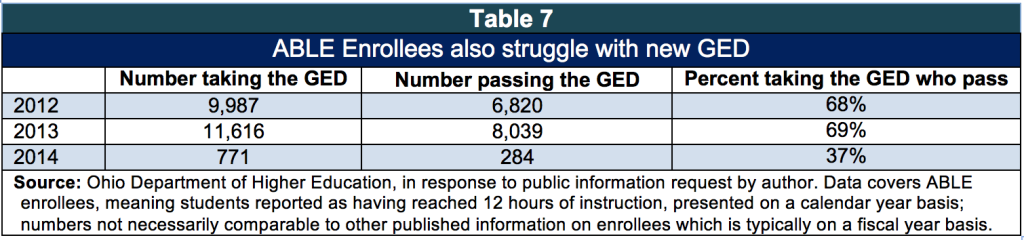

We need more data to compare test performance of ABLE participants, Career-tech enrollees and non-enrollees. We do know that these networks are unable to lift the number of test takers and passers to the pre-2014 levels. Table 7 shows preliminary data from the Ohio Department of Higher Education, that just covers ABLE enrollees.

Even test takers who participated in at least 12 hours of ABLE instruction, with access to guidance and supports provided by the state, have struggled. We have requested data on Ohio’s GED reimbursement voucher program, in an attempt to evaluate whether that program, which drops the cost of the GED back to $40 for first-time takers, was associated with increases in participation or passing. That request is still pending, but in the aggregate it appears that the high school equivalency support system is also struggling with extremely low participation and pass numbers.

The state’s network of ABLE providers and the Career-Tech programs are, with small budgets, serving a population with considerable and diverse challenges. The change in the GED was not accompanied by increases in funding, changes in professional development, or a rubric for targeted evaluation. Rather funding for ABLE declined slightly over the last budget cycle.[33]

It is possible to raise pass rates by increasing test taker supports and improving curriculum, but it is not a complete solution. Kentucky’s Adult Education system has adopted College and Career Ready Standards, which adapt the Common Core to adult education.[34] The state also requires test takers to pass a practice test before attempting the GED. It has a high pass rate, the second highest among states in 2014.[35] But the number of students taking and passing the test remain low. In 2012-13 about 7,083 Kentuckians earned their GED. In 2013-14, only 1,663 had passed. [36] The Kentucky experience suggests that stronger interventions might boost pass rates, but won’t necessarily increase participation or the number of people holding equivalency diplomas. There is no single solution to this problem. Expanding testing options is one part of the solution. Increasing preparation and pre-testing by supporting our ABLE network is another, but without developing alternatives for unsuccessful test takers may only create a different bottleneck in the pathway to post-secondary training. For these reasons, Ohio should undertake a deep evaluation of our basic adult education network and our high school equivalency testing product options.

Recommendations

The Office of Workforce Transformation has said, “What gets measured, gets better.” That is also true for our high school equivalency program. The Ohio Department of Education was either unable or unwilling to timely respond to requests for data about the GED program or the GED reimbursement program. The Ohio Department of Higher Education, which administers the ABLE system, was quicker to respond but had limited data because they are not the administering agency for the GED. We can’t evaluate or improve these programs because the programs are run by different agencies and because an outside party, the GED Testing Service, manages test-taker data. The state must confront these basic issues of data collection, monitoring, and evaluation. Business as usual in this sector puts job seekers, skill seekers, and Ohio employers at a disadvantage. As initial steps toward rebuilding our HSE system, we recommend the following:

Choose testing products that support our workforce goals and our workers

The data suggest that the GED is failing Ohio workers, families, and employers. The state should closely evaluate each alternative high school equivalency product to determine if Ohio should adopt an additional or an alternate exam product. Part of that evaluation should include how each product shares access to test-taker data. GED analytics provide state administrators access to GED data but that process appears to be underused in Ohio. A testing product that can be assessed and that better meets the needs of the population will strengthen Ohio’s skill ladder.

Evaluate the system and get back on track, regardless of the HSE testing product.

Broadly, Ohio should evaluate our system with the express goal of identifying barriers to participation and attainment. The state should develop strategies to help more Ohioans overcome obstacles. As the state’s workforce development system and the state’s cash assistance system are increasingly focused on moving adults and disconnected youth out of poverty and low-paying jobs into family-sustaining jobs, these populations should be a primary focus of a high school equivalency system evaluation. Similarly, since African-American and Latino communities experience higher poverty and lower rates of educational attainment, the state should specifically seek strategies to boost participation and success for these communities. At a minimum, the evaluation should establish regular monitoring and reporting guidelines for the system, and set participation and pass targets. These goals should not be punitive. Much like the workforce development dashboard, the data and evaluation should encourage curiosity about performance and a willingness to proactively make improvements.

Additionally, the Center for Postsecondary Success at the Center for Law and Social Policy has recommended that states develop three categories of strategies to build a robust high school equivalency system.[37] The strategies range from establishing population-specific marketing and recruitment campaigns, with an emphasis on high-poverty areas to increasing professional development around retention and persistence strategies. We recommend this same framework for Ohio.

Invest in our network

Much of the funding for the state ABLE system comes from the federal government. The state does kick in matching funds. Funding for ABLE in 2016 and 2017 is down by about 3 percent from the previous two-year budget cycle.[38] The state has decreased funding for the GED reimbursement vouchers by half.[39] GED administration funds to the education department were reduced sharply when Pearson assumed the role of test and transcript administrator. State support for GED testing, covering education department staffing, oversight of testing sites and processing reimbursements is down 53 percent.[40] This is the wrong direction for a system in real transition and for a state with a mediocre rank in share of residents with this most basic credential.

Additional support for Ohio’s high school equivalency system once came from application fees even though the state no longer receives those fees (Pearson does). Even so, the state has continued to appropriate money to that fund. The state used $1,048,112 from that line in 2014 but $0 in 2015. For the next two years, the state has appropriated $500,000. According to the LSC this line continues to be funded “in case a need for the funding arises.”[41] The decline in the number taking and passing the GED suggests there is an urgent need to evaluate this system, identify alternatives, and increase support to ABLE programs trying to help Ohioans navigate these changes. There are resources for this: Under this administration Ohio has cut taxes by more than $17,000 each year for the top 1 percent of Ohioans, while increasing taxes for the 20 percent with the lowest income.[42] Rather than prioritizing tax cuts, the state could invest in our system and put thousands of Ohioans on a path toward a career, helping employers meet their talent needs, and enriching communities across the state.

The GED is not the launch pad it once was. Rather, changes to the test have resulted in much lower participation and passage. Far fewer Ohioans are able to access this credential. This matters to families, employers, and our economy. Ohio must fix our high school equivalency degree system.

[1] Policy Matters Ohio, the author, and this work are not affiliated with or endorsed by ACE or GED Testing Service LLC. Any reference to “GED” is not intended to imply an affiliation with, or sponsorship by, ACE, GED Testing Service LLC, or any other entity authorized to provide GED® branded goods or services. The GED® is a registered trademark of the American Council on Education (ACE) and administered exclusively by GED Testing Service LLC under license. This report and its content is not endorsed or approved by ACE or GED Testing Service. These disclaimers are made pursuant to the GED Testing Service, “Guidelines for Proper Referential Use of the GED® Trademark by Third Parties,” at http://www.gedtestingservice.com/uploads/files/e340ea4cd47cc1560dc1761d14f0a5eb.pdf accessed December 21, 2015.

[2] See, Daniel J. McGraw, “Making the Case for a Good-Enough Diploma,” November 16, 2015, at http://www.psmag.com/books-and-culture/making-the-case-for-a-good-enough-diploma, accessed December 7, 2015. Daniel J. McGraw, “Nearly 500,000 Fewer Americans Will Pass the GED in 2014 After a Major Overhaul to the Test. Why? And who’s Left Behind,” December 2014, at http://www.clevescene.com/cleveland/after-a-major-overhaul-to-the-ged-test-in-2014-18000-fewer-ohioans-will-pass-the-exam-this-year-than-last-along-with-nearly-500000-across/Content?oid=4442224, accessed December 7, 2015.

[3] Infra at note 8.

[4] This report focuses on non-incarcerated test takers, but the GED test and ABLE/Literacy studies are also part of the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections (DRC), Central School System. Changes in the GED have reduced the number of DRC students receiving diplomas and affected how the system addresses technology and professional development. In 2013, the system reported 3,512 GED students, and 2,121 receiving diplomas. In 2014, the system had 3,889 students and only 1,754 receiving diplomas. See, Office of Offender Reentry, “Ohio Central School System Annual Reports,” 2013 and 2014 at http://www.drc.ohio.gov/web/reports/reports9.asp, accessed December 21, 2015. DRC and the Central School System worked to align their curriculum with the common core standards. Since 2000, DRC has worked to update the computer labs to accommodate the GED changes and create a secure network for running web-based assessments and prep programs. The system also increased professional development and teacher resources.

[5] Policy Matters Ohio calculation from U.S. Census Bureau data, 2014 American Community Survey, Table CP02 Comparative Social Characteristics, accessed December 1, 2015.

[6] Id.

[7] U.S. Census Bureau data, 2014 American Community Survey, Table R1501, Percent of People 25 and over who have completed high school (includes Equivalency).

[8] GED aggregate data from Ohio Department of Education (ODE), current as of September 10, 2015. Data produced in response to a public information request submitted to ODE by Policy Matters in February 2015. Request sought data on takers, completers, and passers by geography and demographics. Request also sought information on the state’s GED voucher program. Appendix A contains all the information on GED participation produced by ODE to date. ODE produced figures on the state’s reimbursement program on February 17, 2016, too late to be included in this report. Unless noted this data does not include changes to the pass rate based on GED’s recalibrated scoring system. Data notes provided by ODE: Data is from the GED Testing Service (GEDTS) database, and may not match data from ODE’s GED database. Historical numbers may vary across data reports due to test-takers who have not “passed” being transferred to their new state of residence. “Tested” refers to individuals who took any individual section of the GED. “Completers” refers to individuals who took all sections (but did not necessarily pass). “Passed” refers to individuals who took all sections and passed.

[9] The decline is measured by the average number passing in the previous five years, to avoid pitfalls in year-to-year comparisons. Many trainers encouraged test-takers to complete the exam in 2013 to avoid the changes, resulting in a mini-surge in 2013. Comparing 2014 to the five-year average mitigates some of those factors, but the result is nearly the same. The number passing fell 85.9 percent between 2013 and 2014.

[10] Nationally, 581,083 and 713,960 completed the GED in 2012 and 2013, respectively. In 2014, that fell to 143,333. The number that passed the GED was 401,388 in 2012, surged to 540,535 in 2013, and dropped to 86,000 in 2014. Duy Pham, Frank Waterous, and Rich Jones, “Expanding Opportunity: The Need for Multiple High School Equivalency Assessment Options in Colorado.” The Bell Policy Center, December 2015, at http://www.bellpolicy.org/research/expanding-opportunity-need-multiple-high-school-equivalency-assessment-options-colorado, accessed December 8, 2015. When the prior five years are averaged, the estimated number completing the GED in 2014 fell by more than 77 percent. The number passing dropped by more than 81 percent. See Washington Post Answer Sheet, Valerie Strauss, “The big problems with Pearson’s new GED high school equivalency test.” The Washington Post, July 9, 2015, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2015/07/09/the-big-problems-with-pearsons-new-ged-high-school-equivalency-test/, accessed December 8, 2015.

[11] See, GED Testing Service, “Score Enhancement Resources,” at http://www.gedtestingservice.com/educators/score-changes, accessed February 11, 2016.

[12] Bill Bush, “GED test change means 1,425 who failed now pass,” The Columbus Dispatch, February 7, 2016, available at http://www.dispatch.com/content/stories/local/2016/02/07/1-ged-test-change-means-1425-who-failed-now-pass.html, accessed February 11, 2016. The Dispatch report included a total for 2015, 4,400 passers with 700 of those being added due to the scoring change. The 2015 total is a data point we have yet to receive from ODE. We have incorporated this newly released information into our report and we note when it is included. In total, the Dispatch reports an additional 1,425 additional Ohioans passed over 2014 and 2015, and about 700 were added to the 2015 total, leaving the remain 725 to be added to the 2014 total.

[13] GED aggregate data from Ohio Department of Education (ODE), current as of September 10, 2015. The number completing the test has also declined. The state averaged 20,184 annual “completers” between 2009 and 2013 but only 4,311 in 2014, a 78.6 percent drop.

[14] See, Daniel J. McGraw, supra at note 1. See also, Duy Pham, Frank Waterous, Rich Jones, supra at fn.10, p.6. The Bell Policy Center’s report features two excellent charts depicting the national data from 2000.

[15] Policy Matters calculation based on the combined difference between the average number passing the GED in the five years before the 2014 changes and the number passing in 2014 and 2015. Difference between the five-year average (14,871) and the total passing in 2014 (2,126) as reported by ODE in September, plus an estimated 725 additional passers created by the score change is 12,021. Difference between the average and the 2015 total of 4,400 as reported by the Columbus Dispatch is 10,472. The total estimated difference is 22,492.

[16] An example of how the GED has impact in unexpected ways: the judiciary system uses the GED as the default for high school equivalency and some judges require obtaining a GED as a probation requirement. However, there is discretion in finding a parole violation for failing the test. Effort and circumstances are considered. Some people on probation make real efforts to pass the test, take the test numerous times, but are unable to pass. Author interview with Franklin Co. Probation officer, December 8, 2015.

[17] Despite its size in the for-profit education industry, Pearson appears to be struggling to keep up with changes in education and technology. According to Bloomberg, the company stock is down more than 40 percent over last year, and is cutting 4,000 jobs to protect shareholders. Controversy over Common Core, which is incorporated into Pearson products, and changes in technology are cited as causes, along with falling textbook demand and lower college enrollment. See, Leila Abboud, “Pearson Buys Time,” Bloomberg, Jan. 21, 2016, available at http://www.bloomberg.com/gadfly/articles/2016-01-21/pearson-buys-time-by-protecting-dividend.

[18] See, Daniel J. McGraw, supra at note 1.

[19] PearsonsVUE does sell fully graded practice tests and guides. They offer a free practice test online, but it is not graded. Accommodations are available to those who can document a “functional limitation.” Pearson evaluates each accommodation request individually. Those seeking an accommodation must make the request through their registration system, have an evaluator (doctor, psychologist) complete an evaluation and the form, then submit the request to the company. See, GED Testing Service, “GED Testing Service Accommodations,” available at http://www.gedtestingservice.com/testers/computer-accommodations, accessed December 8, 2015.

[20] Ohio reimburses the cost for first time test takers. Support for reimbursements was reduced in the 2016-17 state budget. After many requests, the Ohio Department of Education provided limited information on the amount the state has spent on these reimbursements. This information was produced on February 17, 2016, too late to be incorporated into this report. ODE could analyze its own data to determine where vouchers are used and whether those areas show greater attempts or higher passage rates. Preliminary data from ABLE enrollees suggests that supports alone are not sufficient to increase attempts and passage. See, Ohio Department of Higher Education data, Table 7.

[21] US Census Bureau, 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Table B28006.

[22] Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, “2013 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households,” October 2014, available at https://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/2013execsumm.pdf, accessed December 8, 2015.

[23] Noah Berger and Peter Fisher, “A Well Educated Workforce is Key to State Prosperity,” Economic Policy Institute, August 2013, at http://www.epi.org/publication/states-education-productivity-growth-foundations/, accessed December 1, 2015.

[24] U.S. Census Bureau, 2014 American Community Survey, Table S1701: Poverty Status in the past 12 months, accessed December 1, 2015, referring to the Ohio population age 25 and over.

[25] Working Poor Families Project, Population Reference Bureau analysis of 2013 American Community Survey microdata. According to the data 69.2 percent or 280,205 Ohio families are working but earning less than 200 percent of poverty, many would qualify for additional state assistance in the form of food aid, medical aid, and heat supports.

[26] U.S. Census Bureau, 2014 American Community Survey, Table S1501: Educational Attainment, accessed December 1, 2015. These stats cover only the Ohio population age 25 and over. The statewide median wage for 2014 was $49,308.

[27] Policy Matters calculation based on 2014 American Survey data, Tables C15002 B and I, accessed January 26, 2016.

[28] The full details are in Table 9, at http://www.gedtestingservice.com/uploads/files/5b49fc887db0c075da20a68b17d313cd.pdf.

[29] See, ODE, Applying for the GED, available at http://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Testing/Ohio-Options-for-Adult-Diploma/GED/Applying-for-the-GED, accessed December 11, 2015.

[30] Adults who entered ninth grade before July 2014 may also be able to use the new requirements to obtain their diploma by meeting the course requirements, and passing one of the testing options, or making progress toward an industry-recognized credential and passing the Work-keys skills assessment. The courses an individual takes toward a credential may also count for course requirement hours for a high school diploma.

[31] Barry Shaffer, “The Changing Landscape of High School Equivalency,” The Center for Postsecondary and Economic Success at CLASP, May 2015, available at http://www.clasp.org/resources-and-publications/publication-1/The-Changing-Landscape-of-High-School-Equivalency-in-the-U.S.-Final.pdf, accessed December 11, 2015.

[32] The process to request a reimbursement voucher is at http://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Career-Tech/GED-CTPD/GED-Reimbursement-Process, accessed December 9, 2015. The site includes tracking template that logs information about voucher requests. Requests to the Department of Education for information about the number of reimbursements were answered too late to be published in this report. A copy of the “Career and Educational Guidance Document” can be found at http://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Career-Tech/GED-CTPD/GED-Reimbursement-Process/ODE-GED0001.pdf.aspx, accessed December 9, 2015. The document asks why the student is seeking a GED, asks whether they would like an on-site visit to learn about career opportunities, and provides internet links to the state’s job board and “electronic one-stop,” OhioMeansJobs.com.

[33] Infra at note 38. Note that community colleges have GED preparation courses. Some are ABLE sites, such as Cuyahoga Community College, but others, like Columbus State, are not and may charge fees or have addition requirements for enrollment. The full list of Ohio ABLE sites is at https://www.ohiohighered.org/able/locations. A description of the Columbus State GED preparation program, which charges between $99 and $149 per course is at http://www.cscc.edu/community/ged/GED%20Trifold%2016SPNC%20-%20B.pdf. Columbus State does not offer financial assistance for GED classes.

[34] Kentucky Adult Education, College and Career Readiness Standards at http://kyae.ky.gov/educators/ccr.htm, accessed January 26, 2016. See also, Susan Pimentel, “College and Career Readiness Standards for Adult Education,” U.S. Department of Education, April 2013 at http://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/CCRStandardsAdultEd.pdf, accessed January 26, 2016.

[35] See, Debbie Batteiger, “Even with decrease in GED grads, Kentucky has 2nd-highest pass rate,” Murray Ledger & Times, August 17, 2015, available at http://murrayledger.com/news/officials-even-with-decrease-in-ged-grads-kentucky-has-nd/article_385c16cc-4480-11e5-9050-c3bdda0ecb71.html, accessed December 9, 2015.

[36] Ashley Spalding, “Facing Challenges with the New GED Test in Kentucky,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, December 2015, available at http://kypolicy.org/facing-challenges-with-the-new-ged-test-in-kentucky/#fnref-4033-9, accessed January 26, 2016.

[37] Barry Shaffer, supra at note 31 for complete list of strategies.

[38] Policy Matters, calculation based on actuals for 2014, 2015 and appropriations for 2016, 2017, for lines 235443 and 235641, in LSC Greenbook, Department of Higher Education, August 2015, at http://www.lsc.ohio.gov/fiscal/greenbooks131/bor.pdf, accessed January 26, 2016.

[39] LSC Greenbook, Department of Education, August 2015, http://www.lsc.ohio.gov/fiscal/greenbooks131/edu.pdf, accessed January 26, 2016.

[40] Id., Policy Matters Ohio calculation based on actuals for 2014, 2015 and appropriated amounts for 2016, 2017, for lines 200447.

[41] Id. at pg. 73.

[42] Zach Schiller, “Kasich-era tax changes reward the wealthy,” Policy Matters Ohio, August 2015, available at http://www.policymattersohio.org/itep-aug2015, accessed January 26, 2016.

Photo Gallery

1 of 22