Intensifying Impact: State budget cuts deepen pain for Ohio communities

November 13, 2012

Intensifying Impact: State budget cuts deepen pain for Ohio communities

November 13, 2012

Download reportDownload executive summaryCuts in state support to communities across Ohio have deepened, resulting in slashed services, closed facilities and layoffs. Our in-depth analysis provides county-level data on cuts as well as descriptions, from local sources, of the damage done.

Press release

The current state budget for 2012 and 2013 cut local government aid by a billion dollars. This is a big number, but what does it mean? It means cuts in services we depend on, from road repair and emergency services to crossing guards, senior transportation and child protective services. No community or special district escaped the ax: most were hit from many different directions.

The current state budget for 2012 and 2013 cut local government aid by a billion dollars. This is a big number, but what does it mean? It means cuts in services we depend on, from road repair and emergency services to crossing guards, senior transportation and child protective services. No community or special district escaped the ax: most were hit from many different directions.

The economy is improving but cuts are deepening in this the second year of the state budget. A 25 percent cut to Local Government Funds deepened to 50 percent at the start of the second year of this budget period. The loss of hundreds of million more looms as the estate tax, levied on just 8 percent of the wealthiest Ohio estates, is eliminated next year.

Policy Matters Ohio looked at the size and scope of cuts in each county and in many municipalities. We talked with city and county administrators, local elected officials and residents. Community-level data and examples of the local  impact of state budget cuts for all 88 Ohio counties have been compiled into county-level fact sheets that describe the loss in state funding and the impact on cities, towns and services within each county. Because newspaper clips and quotes from local officials are used, this report is not just a presentation of charts and graphs -- it is an oral history. The insights of those interviewed add clarity and depth to a description of hard times.

impact of state budget cuts for all 88 Ohio counties have been compiled into county-level fact sheets that describe the loss in state funding and the impact on cities, towns and services within each county. Because newspaper clips and quotes from local officials are used, this report is not just a presentation of charts and graphs -- it is an oral history. The insights of those interviewed add clarity and depth to a description of hard times.

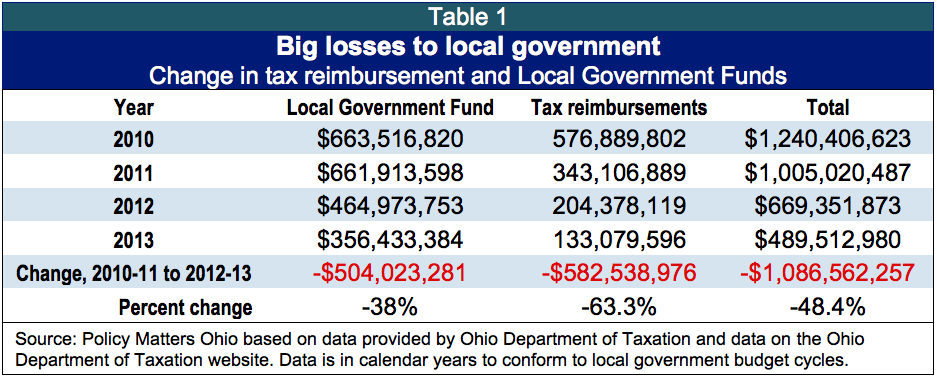

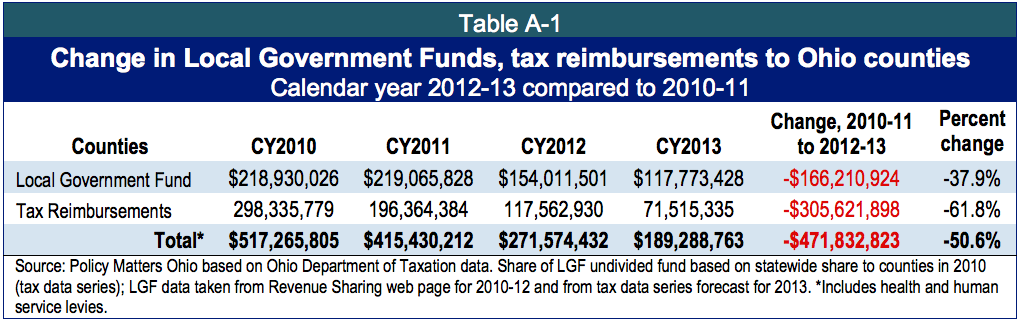

Local government: statewide picture of state budget cuts

The largest cuts in state aid to local government in the current state budget stems from two sources: (1) The Local Government Fund (LGF), a revenue sharing program dating back to 1934 and (2) Tax reimbursements provided to compensate for several local property taxes eliminated as part of tax reductions during the past decade. Using data from the Ohio Department of Taxation, we compared distributions of state aid in the current budget to the prior budget.[1] Losses from these two sources in calendar years 2012-13 total just over a billion dollars,[2] a reduction of nearly half of what was distributed in 2010-11 (Table 1).

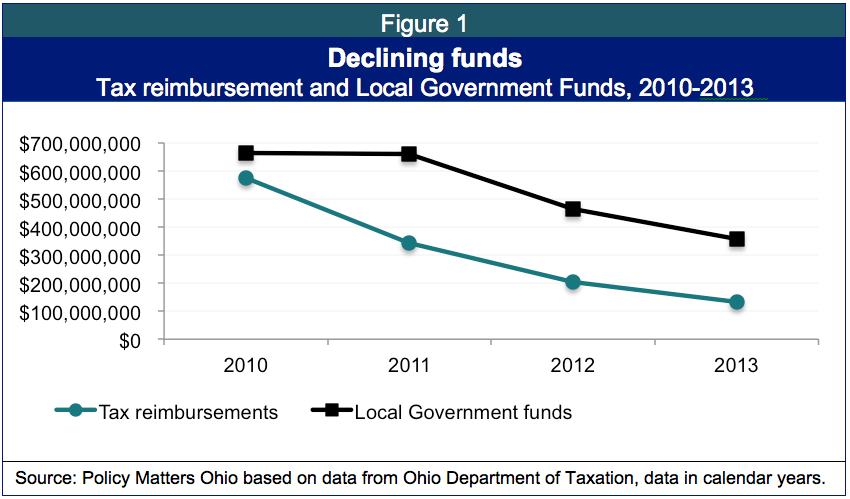

Figure 1 illustrates the phasing in of the cuts over time. Cuts in state aid started with the commencement of the new biennial state budget on July 1, 2011.

Tax reimbursements provided by the state to local governments and special districts were down by $582.5 million in 2012-13 compared to the prior two years, a loss of nearly two-thirds. Losses in this category included:

- Tax reimbursements for the Tangible Personal Property Tax comprised the largest source of revenue loss to local governments, accounting for a loss across the state of $640 million in 2012-13 compared to 2010-11. This reimbursement comes from the Commercial Activity Tax (CAT), and phase-out of that reimbursement was already on the books: local government share of revenue collections from the CAT was to decline from 30 percent to 19.4 percent, a decline of about a third. Under the current state budget, the phase-out was accelerated. The 4,156 levies or jurisdictions impacted by this cut saw their funding decline by 74.1 percent in calendar years 2012-13 from funding levels received during the prior two years, under the former biennial budget, during 2010-11.

- Tax reimbursements for Public Utility Tax. Cuts to local governments in these funds totaled $87 million statewide when compared to what was received in the prior biennial period, an 80 percent decline. This source, though smaller than the other tax reimbursement, was not being phased out.

Local Government Funds, instituted to help counties deal with poverty and plummeting property values during the Great Depression, are cut in the current budget by 25 percent in fiscal year 2012 and 50 percent in fiscal year 2013. The loss in aid comes from two revenues streams of the LGF:

- The Local Government Fund’s “County Undivided Fund” is distributed to Ohio’s 88 counties, which then share the funds internally with municipalities, townships and sometimes parks or public assistance. This fund distributed $464 million less in calendar years 2012-13, which is 38 percent less than distributed during calendar years 2010-11.[3]

- The Local Government Fund’s “Municipal Direct Fund” distributes revenue directly to 582 municipalities. These jurisdictions may expect to see this source reduced by $35 million, or 39 percent less in 2012-13 compared to 2010-11.

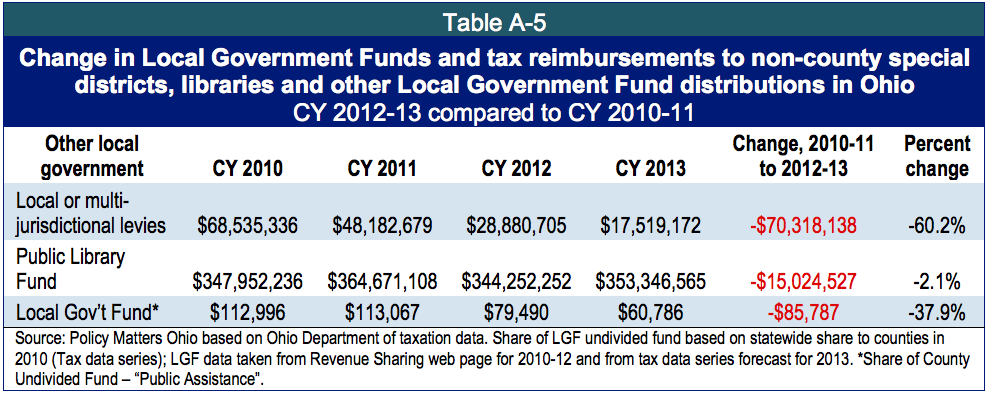

Other funds were cut as well. For example, the Public Library Fund, another branch of local government funding, was reduced by $15 million in calendar years 2012 and 2013 compared to 2010 and 2011; this loss was compounded by loss of tax reimbursements to local library levies, estimated at another $20.8 million. This followed much steeper cuts in state aid in earlier years. The Estate Tax, which impacted the heirs of only 8 percent of Ohio estates, was eliminated in the current budget bill as of 2013. The estate tax brought in $419.2 million in 2011, of which $337.5 million (80 percent) went back to communities. This tax was important to cities, to communities with high-income residents and to townships, which have limited ability to raise revenues compared to municipalities. On average between 2007 and 2010, Cincinnati received $14.36 million each year from the estate tax; Columbus, $7.41 million and Cleveland, $3.77 million.[4] Most jurisdictions received much less, and many saw no funds at all, but hundreds of communities have counted on some income from this source.

Impact on counties, cities, villages, townships, special districts

Ohio is an old and densely populated state, thickly settled with townships, special districts, counties, cities and villages. We are also a “home rule” state, in which citizens and local government have significant autonomy to tailor local laws as long as they do not interfere with state law. Our local governments provide many services that state governments do in much of the rest of the country.

Municipalities – The Ohio Municipal League counts 940 municipalities in Ohio.[5] As a group, municipalities see a loss of $419 million dollars – 45.5 percent – in CY 2012-13 compared to CY 2010-11. Figure 2 shows that the largest source of state aid is from the Local Government Fund’s County Undivided Fund, which is shared with municipalities. Communities that levy an income tax receive an additional, direct allocation of the LGF (“Municipal Direct”); statewide, this accounts for a small portion of the total loss of state aid. Tax reimbursements made up the third component of state aid to communities. Steep declines are seen in Figure 2 in all three categories.

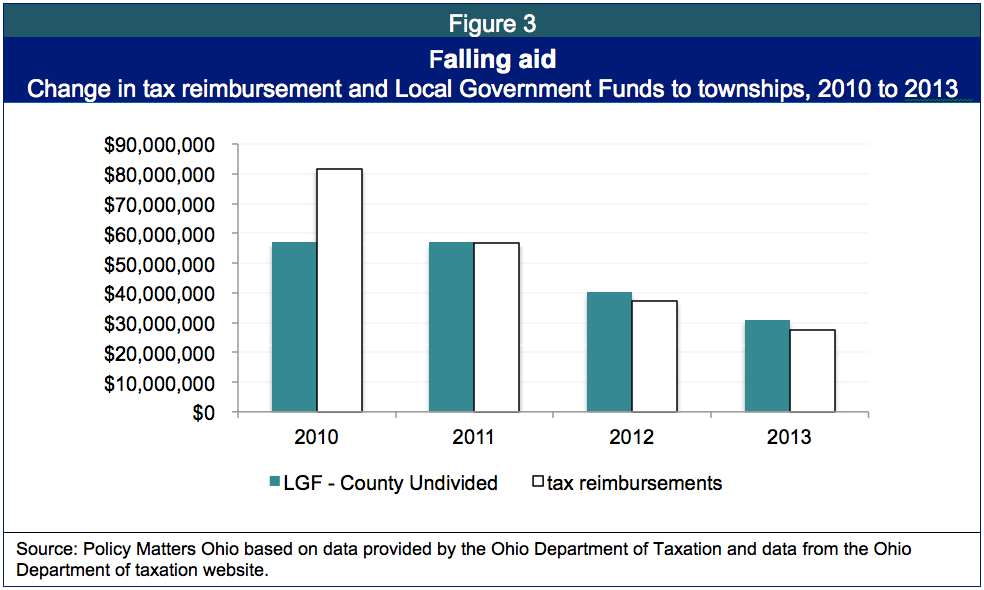

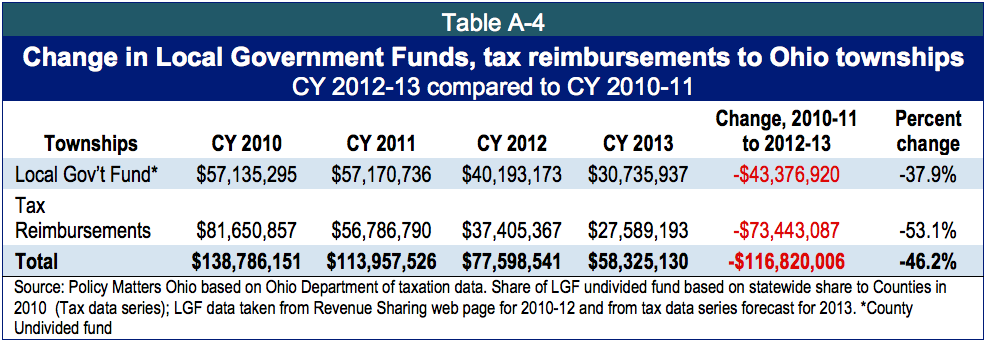

Townships – Townships saw a loss of $116.8 million, a 46 percent decline in state aid compared with the prior biennium, due to cuts to the LGF County Undivided Fund and loss of tax reimbursements (Figure 3). The reduction of tax reimbursements, which were for property taxes eliminated in the past decade, hit townships hard – Ohio’s 1,308 townships have fewer options for raising revenues than the municipalities and rely heavily on local property taxes.

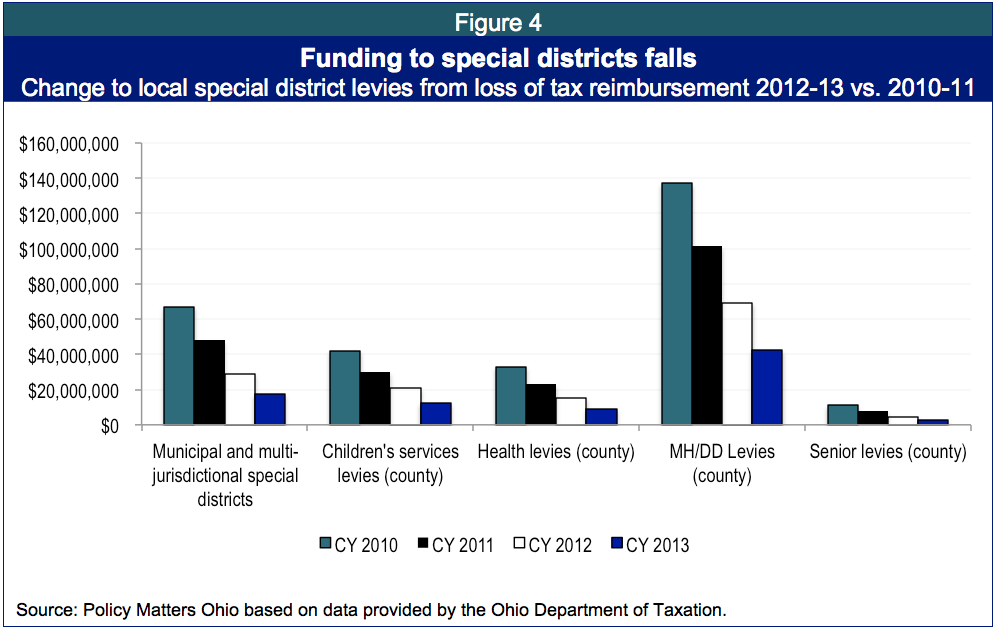

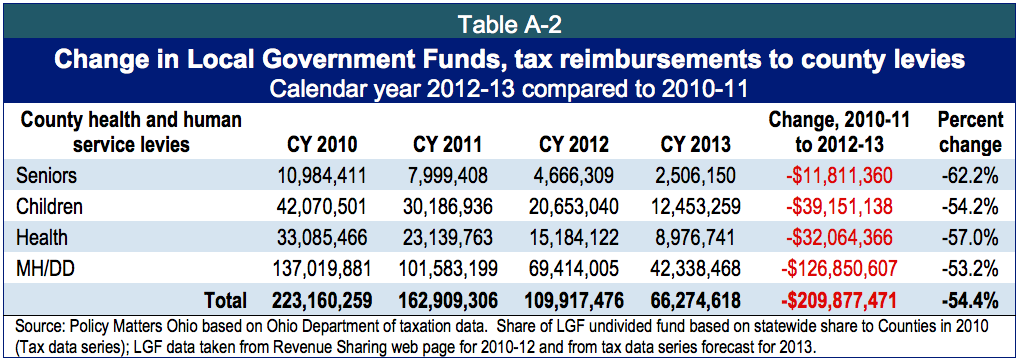

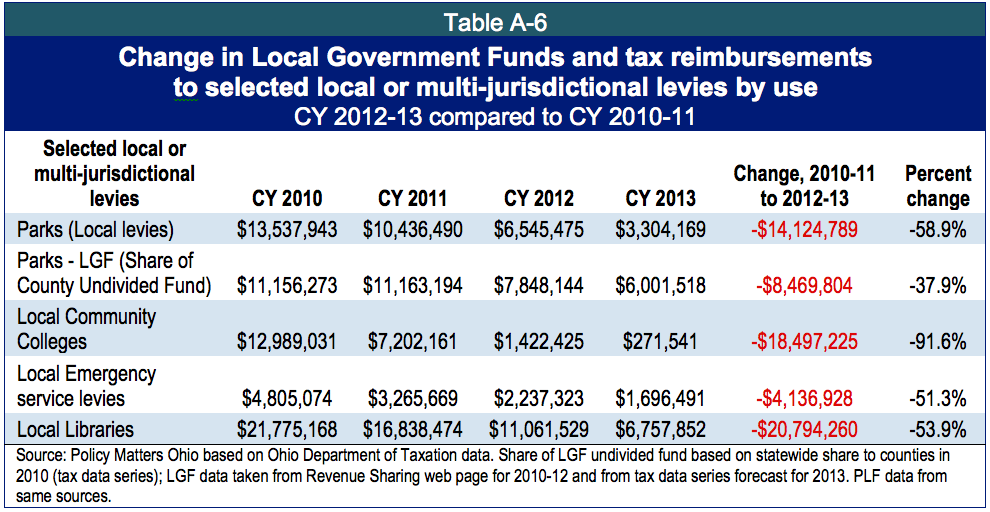

Special districts – There are 65 or more different types of special districts in Ohio. Some are county-wide, some are within one municipality and some are multi-jurisdictional.[7] County levies funding health and human services saw $210 million less in tax reimbursements in the current biennium compared to the last, and multi-jurisdictional or sub-county levies saw a loss of another $70.3 million. This includes county levies for children’s services, which lost $39 million; levies for county health districts, which saw $32 million less; seniors’ levies, which saw almost $12 million less, and mental health and developmental disabilities levies, which lost about $127 million (see Figure 4).

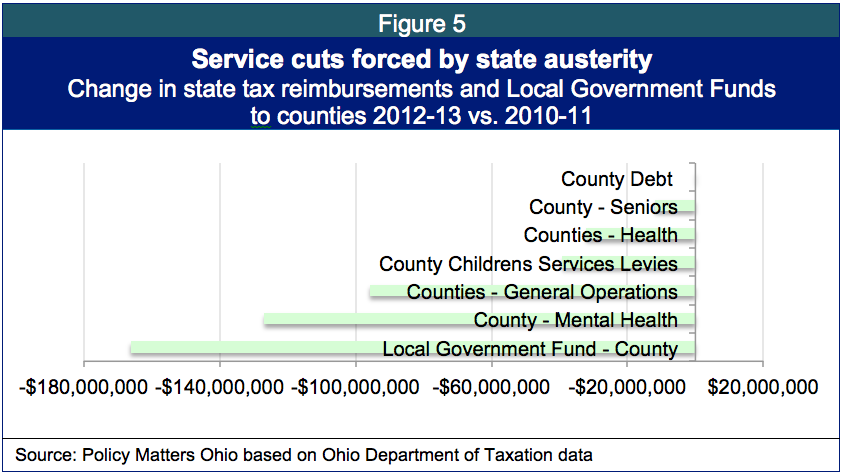

Counties – Ohio’s 88 counties saw $471.8 million less in the current biennium than the last (this includes county-wide special district levies described above). On the county level, the loss of tax reimbursements has been much greater than the loss in Local Government Funds: This reflects the tax reimbursements to specific levies. Nearly half of the cuts to counties reflect a funding loss to levies for health and human services. (Figure 5 and Appendix.)

Public services and quality of life

Revenues pay for services like education, road maintenance, streetlights, emergency services, even cemetery maintenance, and more. In the current budget, legislators made deep cuts to local governments and schools to balance the state budget instead of restoring taxes cut prior to the recession. We see the impact of those choices across the state.

For example, within Hamilton County, an estimated $105 million loss in state aid has impacted the ability to provide services,[8] leading The Cincinnati Enquirer to call for new taxes to address fiscal woes:[9]

“County leaders are quickly approaching the end of the road when it comes to funding essential county services. For next year, a shortfall of $20 million is projected for the county budget, and that means budget cuts ranging from 10 percent to more than 30 percent are proposed. Those cuts would come on top of $44 million that’s already been stripped out of the county’s general fund since 2007. Hamilton County’s proposed 2013 budget is 25 percent smaller than its 2007 budget, and some departments have been cut much more than that.”

The editorial details the cuts to the budget since 2007:

“Next year, the deficit is threatening a county budget that has already suffered years of cuts. Including the cuts proposed for 2013, Jobs and Family Services, which investigates child abuse, will have been cut by 46 percent since 2007; the coroner’s office, which investigates homicides, by 35 percent; the sheriff’s department, which keeps the peace not only in the county but in suburban townships, by 23 percent; the probation department, which tracks freed criminals, by 52 percent. Mundane, but essential county services, such as recording property sales and paying the bills on time, have also been repeatedly cut.”

This is a story heard across Ohio. In this case, the identified problem is fixed debt service payments on capital investment (the new stadiums). As revenues decline, fixed costs take a larger share than planned. The editorial doesn’t mention losses stemming from cuts imposed by the state legislature, but these cuts make it harder to deliver services and carry out fiscal obligations of prior years.

The consequences of the local fiscal crisis may be personal and immediate. A Hamilton County resident at a community meeting of the Ohio Organizing Collaborative in 2011 described being attacked in her front yard in a neighborhood plagued with foreclosed and abandoned houses; she fought off two attackers but lost her purse to a third while she called for help. Help came, but too late. This is an extreme consequence of the fraying of civic life, but there are frayed ends across the state. In addition to violation of personal safety, consequences can include erosion of wealth as quality of life is diminished and property values fall. In Mansfield, streetlights have been dimmed on a rolling basis as the city copes with a fiscal emergency. Road and bridge repairs worry local officials: Uncertainty around state aid makes new debt service look risky, even if credit rating is good.[10] Infrastructure concerns large and small abound across the state. In University Heights, some streets look like patchwork quilts, causing concern about property values.

“When one island in the archipelago starts to sink, the entire archipelago is destabilized,” says Councilman James O’Reilly of Wyoming, a suburb of Cincinnati. Councilman O’Reilly worries about attracting newcomers to his residential community. He describes a young couple from Europe who recently moved into Wyoming, attracted by a walkable downtown, good schools and a friendly community spirit. “Realtors know where quality of life is good, and they guide their clients to those places,” he observes. “We have been cutting services since the recession. What if budget shortfalls destabilize our ability to attract new families? Our property values fall, our tax base falls, our island is destabilized. Some of our neighbors are already destabilized.”[11]

Ohio’s landscape is littered with the detritus of private sector disinvestment: shuttered factories and abandoned strip malls. The Mayor of Norwood has battled disinvestment for 20 years, with important successes. “GM was shuttered a long time ago,” he points out. “We’ve rebuilt.” Montgomery Street is busy, with shopping centers parked full and sidewalks bustling. But the mayor and his department heads worry about the future.

“It looks pretty good now, but we’ve worked hard to get state and federal special grants. Next year federal aid will be cut, but we still need those funds. Today we have hundreds of foreclosed and abandoned homes in the neighborhoods; just boarding them up costs money.” He shakes his head. “If the thieves paid an earning tax on copper, we might have a chance.”[12]

Norwood city employees have seen their wages frozen and have given concessions. Staffing has been curtailed through attrition. If the Local Government Fund is completely eradicated in the next budget, it will eliminate close to $700,000 every year out of the budget. Two swimming pools have been closed. Senior services have been cut. Building permit and occupancy fees have been boosted.

“I agree with the governor about the Severance Tax,” says the Georgine Welo, mayor of South Euclid, referring to Gov. Kasich’s proposal to increase taxes on the oil and gas drilling industry, which he would use to cut individual income taxes. “It’s a growth sector, a new industry, and should pay a fair share. But not for more tax cuts. These funds could be used to restore schools, to provide decent public transportation, to bring the cloud to Ohio. What attracts residents? Amenities. Ohio is a very attractive state, but we need to boost amenities in our communities to keep people here.”[13]

Sources of local savings

The mayor of Eastlake voiced the concerns of many last summer as state savings garnered in the Corrections Bill (House Bill 487) and overage from revenue growth were put into the rainy day fund or uses other than local services: “From Eastlake alone, he took $1.5 million, or 11 percent of our general fund. We had to lay off police officers, firefighters, Service Department employees and office workers...”[14]

Communities close budget gaps through wage freezes, layoffs, putting off repairs of all kinds, increasing fees, privatizing and cutting services. Ohio has lost 33,500 jobs in the local government sector since the end of the recession.[15] Communities tend to freeze wages, reduce benefits, and let jobs go unfilled before they resort to layoffs. Some now see hopeful signs of a strengthening economy. “We are seeing rebound in the economy,” says Akron Finance Director Diane Dawson-Miller. “But loss of state funds hinders our ability to restore services.”[16]

Staff cuts in human services have been deep since the recession, even as demand has increased. Inadequate staffing has reached crisis levels in some places. There are tragic incidents reported in the child protection system from time to time. But even short of such tragedies, funding gaps add stress. In an arbitration case heard by the State Employee Relations Board last year, a reversal of a disciplinary action cited working conditions as contributing to lack of oversight:

“She [the caseworker] was operating under an emergency and systemic collapse due to assignment of 6 caseworker caseloads that were only being attended to by one caseworker and a supervisor who was not expected to make home visits.”[17]

The case was from southwest Ohio, where county children’s services struggle with deep cuts that started during the recession. The Cincinnati Enquirer examined such problems, publishing a memo Hamilton County JFS Director Moira Weir wrote asking for $2 million to hire more social workers and supervisors.

“When you reduce 50 percent of your staff because of a 50 percent reduction in funding it will certainly have an impact on your organization. I’m looking for ways to relieve the pressure on the staff so they can do the true work – protecting children.”[18]

The problem emerges in other local health and human services. “There is no safety net for behavioral health in Ohio,” says William Denihan, President of the Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services (ADAMHS) board of Cuyahoga County. “At some times, we cannot accommodate new people. Intake was closed for 6 weeks. Staffing has been reduced from 101 to 47. We serve many, but research shows there are thousands more who need these services that we cannot accommodate.”[19] Needs are great, yet state aid to local MH/DD levies was reduced by $126 million in the current two-year period.

Some interviewees spoke of deferred building repair and equipment replacement due to budget shortfalls. The estate tax, which is not predictable but provides substantial resources to nearly all communities from time to time and to many communities on an annual basis, has in many places been the source of funds for replacing emergency service equipment like fire engines and ambulances, police cars, mowers, road repair equipment and other large items. With the elimination of the estate tax, these purchases will be forced into general fund budgets.

Among other service cuts attributed to loss of state aid, many mentioned reduction in services to or facilities for seniors and youth. Crossing guards and senior transit personnel are gone in many places. Swimming pools have been closed, basketball courts locked. Waste removal and trash collection are curtailed. Many places have reduced police and fire personnel. Some jurisdictions seek savings by dimming streetlights. Last year the Mansfield News Journal reported:

“Nearly 15 percent of the city’s street lights will be turned off this month as part of a plan to cut costs…. A total of 766 of Mansfield’s 5,200 streetlights will be turned off for two years, city officials announced today. City Engineer James DeSanto said the action is part of Mansfield’s financial recovery plan from fiscal emergency. It is expected to save more than $185,000.”[20]

Some of Ohio's local parks are feeling the pain of state budget cuts. The Johnny Appleseed Metro Park District near Lima anticipates the loss of more than $325,000 dollars in next year's $1.1 million dollar budget. Parks Director Kevin Haver says they're using more fuel-efficient vehicles and mowing less acreage; they have five fewer employees and they leave the entry gates open and unlocked at night.[21] Political columnist Mark Naymik of the Cleveland Plain Dealer describes the degraded condition of Cleveland’s beaches.

“The state's operating budget for the lakefront park system is $2.2 million in fiscal year 2012, up slightly from the $1.9 spent in 2011. The state has spent hundreds of thousands on dredging and infrastructure repairs since 2005….. It's obviously not enough. The state could find more cash for upkeep in its budget surplus, which was $300 million and growing in May, but that is not likely.”[22]

Some jurisdictions have privatized services, although research shows that for a variety of reasons – ranging from inflexibility in contracts to proper monitoring and oversight – such privatization can backfire and raise costs.[23] Garbage and waste collection was the primary service privatized. The city of Toledo privatized these services in the quarter before the state budget was passed. Along with the privatization, fees were raised on residents for the service. In other communities, fees are on the rise for building permits, inspections, water, occupancy and streetlights, as well as for garbage, dumping and solid waste pick-up.

Across communities, public workers are doing double duty, as recreation personnel take on grounds maintenance and waste control, grounds crews train as arborists and fill potholes. Middle management has been eliminated; whole classifications and departments have vanished; divisions barter among themselves for office supplies. A high priority is placed on strategies for stimulating the real estate market and attracting new residents: for example, South Euclid targeted seniors and with the aid of the Cleveland Insitute of Art developed a home retrofit model for ‘Aging in Place’ to keep – and attract – retirees.

Local governments in Ohio have pursued collaboration for a variety of reasons, including improving quality of services, extending service geography, improving process or saving costs. Cost savings are touted, but there is no assurance of success. In a state with a long tradition of home rule, adjoining communities might differ widely about what constitutes a civic good.

A 2011 Wall Street Journal story reported that combining small governments through merger can sometimes increase costs:

“Governors and lawmakers across the U.S., looking to trim the costs of local government, are prodding school districts, townships and other entities to combine into bigger jurisdictions. But a number of studies—and evidence from past consolidations—suggest such mergers rarely save money, and in many cases, they end up raising costs.” [24]

A 2009 Wright State University study documented that 92.3 percent of 400 Ohio communities participating in a survey on the topic of local collaboration had formal or informal collaborative arrangements with neighboring jurisdictions.[25] A study by researchers at Kent State University the same year found local governments collaborating, but not just for the purpose of cost savings. Almost a third of the collaborations they studied had yielded cost savings and another quarter of respondents thought cost savings were possible in the future. Another third, however, did not anticipate cost savings and 12 percent simply did not know.[26] The current state budget established a competitive fund of grants and loans to underwrite feasibility studies for collaboration, and interest in the fund is robust. These studies indicate that cost savings may not be a sure bet, particularly compared to cuts in aid.

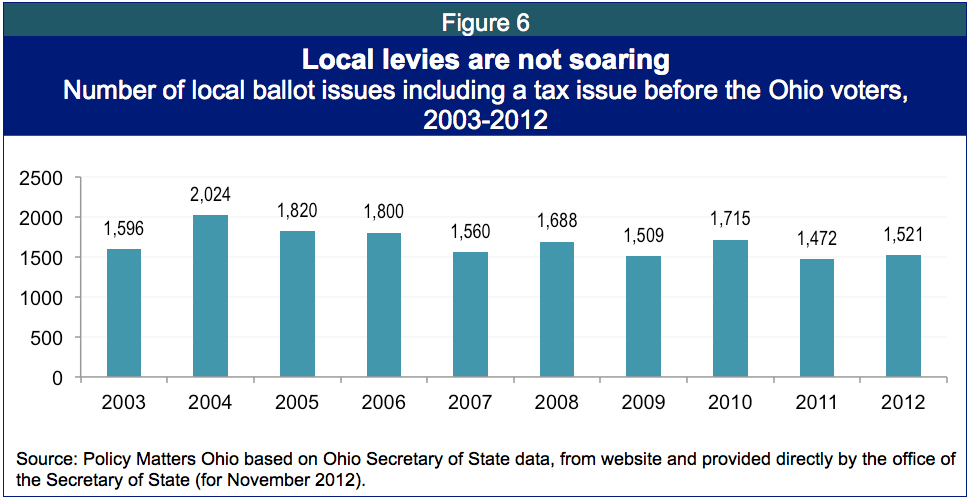

Some local governments anticipate new revenues and/or have initiated levies and raised fees. The first installment of casino revenue funds were distributed July 31 to eight cities and all 88 counties. While these funds will help to a degree, they will not replace state aid cut to date.[27] Nor is there a dash to the polls for local taxpayer relief. Figure 5, taken from data on the Ohio Secretary of State website, indicates that through 2012, local levies overall have not soared in number compared to prior years.

Local governments don’t take the decision to go to the voters lightly. The city of Shaker Heights, facing an annual budget gap of $6.5 million, is one of few communities where voters approved an income-tax hike. The ballot issue was put to a vote after careful consideration by committee of residents and business leaders that included hearings as well as studies.[28] Shaker Heights prides itself on strong public services, and residents are perhaps more willing, and able, than those in other communities to pick up where the state cut. Yet communities with greater challenges are also preparing for local tax increases. Lorain, facing a $2 million budget gap in 2013, is preparing for an income tax levy.[29] Levies have met with mixed success. Schools have seen broad support for renewals but a general lack of support for new levies. According to the Ohio Township Association, residents have supported Township levies; they found 85 percent of township levies placed on the ballot in November of 2011 were approved:

“Despite recent cuts in local government funding and a difficult economy, township residents clearly recognize the need for essential services, such as fire and police protection, and cemetery and road maintenance. Support for townships was reflected in the high number of levies which passed recently. Statewide, 475 township levies were on the Nov. 8 ballot. Of the 475, 408 passed for a rate of 85 percent. On the flip side, only 63 failed. The results of four levies have not been finalized due to close votes. Levies ranged from fire, police and EMS to general revenue, electric aggregation and parks. Fire protection accounted for the highest number of levies passed.” [30]

Some places, like Noble County, have gotten levies approved only to see them repealed. In Westerville, opponents to a school levy approved by the voters sought to repeal it, but their effort was ruled off the ballot.

Conclusion and recommendations

The public sector is the platform upon which private wealth, both residential and commercial, is built. How far can we cut it before our common wealth starts to erode? It’s a question that concerns our economy and our quality of life.

Deep cuts have been made to all local governments and to special districts. Health and human service levies were hit especially hard, losing 54 percent of state aid, on average. Impacts range from the inconvenient – curtailed hours at county buildings, reduced yard waste services – to the tragic. Children’s services in Hamilton County have been slashed, and behavioral health problems are going untreated in Cuyahoga County. Even issues such as uncontrolled and unpatrolled foreclosures, dimmed streetlights and lengthened emergency response times are testament to the harm cuts have inflicted, and will continue to inflict, on Ohioans’ personal safety as well as to property values and family wealth.

The county auditor of Wayne County articulated the challenge Ohio faces, pointing out that voters elected an administration that promised smaller government and is actively pursuing campaign promises. This gives people a chance to experience what the shrinking of government, especially local government, feels like.[31] Future elections will give voters the opportunity to change direction.

State legislators would do well to listen to what is happening at home. The cuts are already too deep. The pending budget offers an opportunity to consider a more balanced approach to rebuilding Ohio’s common wealth and job base. It is time for investment for the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank county auditors, Ohio Children and Families First coordinators, and other local government and health and human service officials in all 88 counties and many municipalities who spoke to our team over the summer. In particular, we are grateful to: Mayor Earl M. Leiken of Shaker Heights; Mayor Georgine Welo and her staff of South Euclid; Councilman James T. Reilly and City Manager Lynn Tetley of Wyoming; Mayor Tom Williams, Treasurer Tim Malony and Councilman Joe Sanker of Norwood; Mayor J.K. Byar and Vice Mayor Natalie Wolf of Amberley; Sharon Dumas of Cleveland; Mayor Susan Infeld of University Heights; Diane Dawson Miler of Akron; Tim Riordan of Dayton; Mayor David Berger of Lima; Mayor Mike Summers of Lakewood; State Representative Denise Driehaus; Shelby County Auditor Denny York; Reginald Zeno of Cincinnati; President and CEO William Denihan of the Cuyahoga County ADAMHS Board.

We would also like to thank the many interns who assisted with this project: Casey Andersen, Morgyn-Britney Hall, Laura Harris, Marcy Jagdeo, Ellen Kubit, Andrew Loucky, Phoung Lee, Stephen Maillard, Victor Matsunaga, Timothy O’Toole, Alex Saunders, Robin Steiner, Alex Vitale.

Appendix

As throughout this report, numbers in Table A-1 through A-5 cover calendar years, while major reductions in Local Government Funds and tax reimbursements were approved for fiscal years 2012 and 2013. Calendar years are used here because local governments budget on the calendar year, and therefore the Ohio Department of Taxation projects distributions of aid and of tax collections on a calendar year basis. The forecasts for 2013 are uncertain because the legislature is required to enact another biennial budget by the end of June 2013 and further changes might be incorporated in it. For the purposes of this report, calendar year projections required for the Local Government Fund are provided for 2013 by the Ohio Department of Taxation. Both distributions and projections of tax reimbursements for 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013 were provided by the Ohio Department of Taxation.

[1] The funding throughout this brief is analyzed on a calendar year basis, because local governments operate on a calendar year basis and Department of Taxation data is configured for their uses.

[2] This figure does include loss of Dealers in Intangibles Tax, which is distributed as part of the Local Government Fund. It does not include the Public Library Fund, the Estate Tax (eliminated in 2013), school district losses or other cuts.

[3] This assumes no further cuts in the next biennium, which starts July 1, 2013 and begins to impact local governments in the fall of 2013; forecast for the entire calendar year of 2013 is based on Ohio Department of Taxation, Tax Data Series at http://tax.ohio.gov/divisions/tax_analysis/tax_data_series/local_government_funds/publications_tds_local.stm.

[4] Zach Schiller et..al., “No Windfall: Casino taxes won’t make up cuts to local governments,” Policy Matters Ohio (October 2012) at http://www.policymattersohio.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/CasinoTaxes_oct2012.pdf

[5] Sue Cave, The Ohio Municipal League, “Municipal Revenues, Municipal Expenditures, Municipal Services: An Overview,” Testimony the General Assembly, January 18, 2011. Provided by Gongwer News Service.

[6] Ohio Township Association, 2011-12 Legislative Priorities at http://bit.ly/SPPy9B.

[7] An example is the health district, which deals with issues of public health. Every Ohio resident lives in a health district. It may be either a city health district or a general health district. Every city must have a health district, unless it chooses to become part of a general health district; a general health district consists of all the territory of a county not within a city health district. The general health district is primarily funded from apportionments from the tax levies of the townships and municipalities in the district, and from separate health district tax levies. Other special districts have a formal structure as well. OSU Agricultural Extension, Ohioline Bulletin #835: “Local Government Structure and Finance.”

[8] Cuts hurt Ohio at http://www.cutshurtohio.com/

[9] “It’s time to talk about the T-word,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 26, 2012 http://cin.ci/VTCfVy.

[10] Interview with City of Lima Finance Director Steve Cleves, June 27, 2012.

[11] Interview with Councilman James T. O’Reilly of Wyoming, May 25, 2012

[12] Interview with Mayor Thomas F. Williams of Norwood, May 25, 2012.

[13] Interview with Mayor Georgine Welo of South Euclid, May 5, 2012.

[14] “Kasich’s surplus came from the budgets of busted cities” at http://bit.ly/U4TAJw. (Accessed August 30, 2012).

[15] Ohio Labor Market Information, Current Employment Statistics (June 2009 to September 2012) at http://ohiolmi.com/asp/CES/CES.htm: this is based on monthly estimates, highly variable and subject to revision.

[16] Interview with Diane Dawson Miller, Akron finance director, June 22, 2012.

[17] This case started in 2007, the first year of the recession. Arbitration proceedings, FMCS # 10-56843-8; Date of Award – July 28, 2011.

[18] Sharon Coolidge, “Could 2-year old James Livesay have been saved?” Enquirer/cincinnati.com, April 20, 2012.

[19] Interview with William Denihan and colleagues January 5, 2012.

[20] “Turn Out the Lights, Mansfield’s saving Money,” Mansfield News Journal, http://www.municipalinsider.com/news-stories/turn-out-the-lights-mansfields-saving-money/ (Accessed August 30, 2012.)

[21] “Budget Cuts at The Parks”, June 4, 2012, www.hometownstations.com/story/18692938/budget-cuts-at-the-parks.

[22] Mark Naymik, “Cleveland's state-run lakefront parks are embarrassing”, The Plain Dealer at at www.cleveland.com/naymik/index.ssf/2012/06/clevelands_state-run_lakefront.html

[23] “Privatization Myths Debunked,” In the Public Interest at www.inthepublicinterest.org/node/457.

[24] Conner Dougherty, “When Civic Mergers Don’t Save Money,” Wall Street Journal, August 21, 2011 at online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424053111904875404576532342236074926.html.

[25] Jack Dustin, David Jones, and Myron Levine, “Collaborative Local Government in the State of Ohio,” Wright State University, 2009 at www.greaterohio.org/files/policy-research/wright-state-report.pdf.

[26] John Hoornbeek, Ph.D., Kerry Macomber, MPA, Melissa Phillips, Sayantani Satpathi, “Local Government Collaboration in Ohio: Are we walking the walk or just talking the talk?” Kent State University, 2009 at http://www.kent.edu/cpapp/research/upload/local-government-collaboration-in-ohio-report.pdf

[27] Schiller et.al., “No Windfall,” Policy Matters Ohio at http://www.policymattersohio.org/casino-taxes-oct2012

[28] Mayor Earl M. Leiken’s e-news, March 30, 2012.

[29] “Lorain’s Future and the Income Tax,” June 25, 2012, power point presentation of the City of Lorain.

[30] Ohio Township Trustees’ News Release, 11/01/2011 at http://bit.ly/U9Qx2L. (Accessed 8/30/2012)

[31] Telephone interview with Wayne County Auditor Jarra L. Underwood, July 2012.

Tags

2012Budget PolicyRevenue & BudgetSustainable CommunitiesWendy PattonPhoto Gallery

1 of 22