Public Assistance Initiatives in 2014 Ohio Budget Bill

July 22, 2014

Public Assistance Initiatives in 2014 Ohio Budget Bill

July 22, 2014

Download summary (2pp)Download report (10pp)Press releaseChanges to public assistance programs in the MBR emphasize cost cutting, stricter eligibility, but not alleviation of poverty.

Will they help Ohio families?

The Mid Biennium Review (MBR) included five new initiatives aimed at requiring or helping recipients of public assistance get jobs and reduce reliance on public assistance programs. Many who get public assistance already have a job, but they don’t make enough to feed themselves and their families, see a doctor, or pay for childcare. Public benefits stabilize family life and support success at work. Reducing public assistance could do harm in today’s low-wage economy. However, updating programs to better serve the needs of the labor market could help many Ohioans. Finding ways to reduce the incidence and impact of poverty remains critically important as well. Interventions like job training, education, substance abuse and mental health treatment are not likely to work for people whose basic human needs are not met.[1]

The Mid Biennium Review (MBR) included five new initiatives aimed at requiring or helping recipients of public assistance get jobs and reduce reliance on public assistance programs. Many who get public assistance already have a job, but they don’t make enough to feed themselves and their families, see a doctor, or pay for childcare. Public benefits stabilize family life and support success at work. Reducing public assistance could do harm in today’s low-wage economy. However, updating programs to better serve the needs of the labor market could help many Ohioans. Finding ways to reduce the incidence and impact of poverty remains critically important as well. Interventions like job training, education, substance abuse and mental health treatment are not likely to work for people whose basic human needs are not met.[1]

This brief describes the five initiatives of the MBR as well as several basic public assistance programs. We examine wage levels in Ohio’s largest job groups and find they are so low that a working parent with two children in almost any of these occupations could be eligible for public assistance. The cost of self-sufficiency is far higher than what many jobs pay – which is why many working Ohio families need help putting food on the table, paying the childcare center and seeing the doctor.

Initiatives on public assistance

1) Office of Human Services Innovation - (Ohio Revised Code [ORC] Section 5101.061)

House Bill (HB) 483 created the Office of Human Services Innovation within the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services (ODJFS) to coordinate and reform public assistance programs and to coordinate services across all public assistance programs. Goals and activities stated in the legislation include:

- To help individuals find employment, succeed at work, and stay out of poverty;

- To revise incentives for public assistance programs to foster person-centered case management;

- To standardize and automate eligibility determination policies and processes for public assistance programs, and

- Other matters considered appropriate.

The Superintendent of Public Instruction, Chancellor of the Ohio Board of Regents, Director of the Governor's Office of Workforce Transformation and the Director of the Governor's Office of Health Transformation will join the Director of Job and Family Services in leading the office. A report is due by January 1, 2015.

2) County job and family service departments and caseworker evaluation (ORC Section 5101.90). County departments, caseworkers and contractors are to be evaluated in terms of their success helping program participants get jobs that enable them to ‘cease relying on public assistance.’ The definition of ‘public assistance’ is tied to statutory language of Ohio Revised Code 5101.26.

3) Ohio Works First Employment Incentive Pilot Program (ORC Section 751.35). This initiative establishes a pilot program that provides bonuses to caseworkers or contractors for placing Ohio Works First participants in jobs. Three-year pilot programs for five counties are funded at $50,000 each; after three years, a report with recommendations on the programs is to be published.

4) Workgroup to reduce public assistance reliance (ORC Section 751.37). This initiative requires the Governor to convene a workgroup to develop proposals to help individuals stop relying on public assistance as defined in ORC section 5101.26. It will consist of representatives of directors of urban and rural county job and family service departments and representatives of county commissioners of urban and rural counties. The Governor is to appoint the members of the group within 30 days and the group is to produce a report six months after the workgroup is appointed.

5) The ‘Healthier Ohio Buckeye Advisory Council’ (ORC Section 5101.91) The Governor’s Office will convene this group to facilitate outcomes of county-level ‘Healthier Buckeye Councils,’ created in Senate Bill 206 of the 130th General Assembly. Healthier Buckeye Councils were created to recommend ways to reduce the reliance of individuals and families on publicly funded assistance programs, using both of the following:

- Programs that have been demonstrated to be effective and have one or more of the following features: Low costs; use of volunteer workers; use of incentives to encourage designated behaviors; are led by peers.

- Practices that identify and seek to eliminate barriers to achieving greater financial independence for individuals and families who receive services from or participate in programs operated by council members or the entities the members represent.

County councils are also to promote care coordination among physical health, behavioral health, social, employment, education, and housing service providers within the county and to collect and analyze data regarding individuals or families who receive services from or participate in programs operated by council members or the entities the members represent. The ‘Healthier Buckeye Advisory Council’ in the Governors Office is to:

- Develop means by which the county councils may reduce reliance on public assistance;

- Recommend eligibility criteria, application processes, and maximum grant amounts for an Ohio Healthier Buckeye Grant Program;

- Provide recommendations for coordinating services across all public assistance programs;

- Revise incentives for public assistance programs to foster person-centered case management;

- Give recommendations on how to standardize and automate eligibility determination policies and processes for public assistance programs.

Like the Office of Human Service Innovation, the Healthier Buckeye Advisory Council is to be led by the Director of Jobs and Family Services. Members include:

- Five members representing affected local private employers or local faith-based, charitable, nonprofit, or public entities or individuals participating in the Healthier Buckeye Grant Program, appointed by the Governor;

- Two members of the Senate, one from the majority party and one from the minority party, appointed by the President of the Senate;

- Two members of the house of representatives, one from the majority party and one from the minority party, appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives;

- One member representing the judicial branch of government, appointed by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court;

- Additional members representing any other entities or organizations the director of job and family services determines are necessary, appointed by the Governor.

What is public assistance?

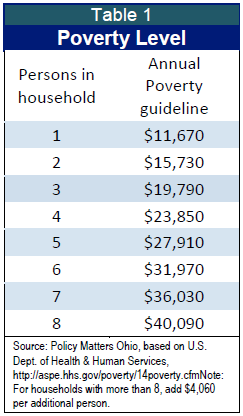

Public assistance programs are primarily federally funded, although the state provides matching funds. Benefits are tied to national poverty guidelines (Table 1). Families are eligible for help if their income is close to or less than the poverty level. Some forms of public assistance are explicitly “work supports” in that workers would be unable to retain their job without them. Childcare assistance or help with transit fall firmly in that category. A parent may be unable to take a low-wage job unless childcare assistance allows her to make sure her children are safe while she is at work.

Public assistance programs are primarily federally funded, although the state provides matching funds. Benefits are tied to national poverty guidelines (Table 1). Families are eligible for help if their income is close to or less than the poverty level. Some forms of public assistance are explicitly “work supports” in that workers would be unable to retain their job without them. Childcare assistance or help with transit fall firmly in that category. A parent may be unable to take a low-wage job unless childcare assistance allows her to make sure her children are safe while she is at work.

Other programs simply help low-wage families get by in jobs that don’t fully meet needs. Medicaid is a good example. Access to a doctor on a regular basis allows people to better control chronic disease and lead healthier, more productive lives. Medical crises that can lead to job loss and economic disaster – like foreclosure - may be prevented by consistent health care.

Four public assistance programs are described here: cash assistance, food aid, childcare and health care.

Cash Assistance: Households with minor children and income half of the poverty level or less are eligible for ‘Ohio Works First,’ the cash assistance program under Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). In Ohio, families this poor may receive cash assistance for 36 months in a lifetime (federal rules permit up to 60 months, but Ohio limits it to 36 months). Just over 100,000 children are enrolled in Ohio Works First.[2] Parents in the program who are not disabled must work: almost 8,000 of the 19,000 adults in the program work.[3] Benefits are very low. In 2013, the benefit for a family of three was $465 per month (less than $5600 per year).[4]

Food aid is critically important to many Ohio families. The state ranks 10th nationally in number of households that regularly lack enough money for food.[5] In April of 2014, there were 1.76 million Ohioans relying on the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (food assistance) in Ohio; 42 percent are children.[6] Under federal law, food aid is limited to families with gross income of less than 130 percent of poverty, and net income of poverty or less.[7] Adults who are not disabled, who have no children and who are between 18 and 50 years of age can get food aid for just 3 out of 36 months if they are not working.[8] The average monthly food assistance in Ohio in 2013 was $130 per month per individual or $267, on average, for a household.[9]

Medicaid provides health care for families and children; aged, blind and disabled individuals and, under Medicaid expansion, adults of very low income. Children in households with income up to 200 percent of poverty and adults in households with income up to 138 percent of poverty are eligible. In April 2014, 2.5 million Ohioans received health care through Medicaid.[10] In 2013, more than half of Medicaid recipients were children.[11] While Medicaid supports workers by allowing them to see a doctor, it has a broader purpose in meeting basic human needs.

Public childcare assistance is for families with parents who are working or in school. Families are eligible to enroll in this program if they earn 125 percent of poverty or less.[12] Once in the program, families can stay in until their income rises to 200 percent of poverty, but program tracking indicates few get to this point.[13] Changes in hours, shifts, and even jobs common in many low-wage occupations keep families bouncing in and out of eligibility and out of the program.[14]

Changes in poverty, impact of policy

Poverty has been on the rise in the nation and in Ohio.[15] A family of a single parent with two children earning less than $10,000 a year (working 23 hours per week at minimum wage) is living at 50 percent of the poverty level, in deep poverty.[16] The share of Ohioans this poor grew from 4.6 percent in 2000 to 7.6 percent in 2012, the third greatest jump among all the states.[17] The share of Ohio children living in deep poverty rose from 9 percent in 2006 to 12 percent in 2012.[18]

Ohio’s aid to the poorest households through Ohio Works First, the state’s cash assistance program under TANF, has fallen sharply (Figure 1). Adult participation in Ohio Works First dropped by 71.3 percent while child participation dropped by 40.2 percent between January of 2011 and June 2014.[19]

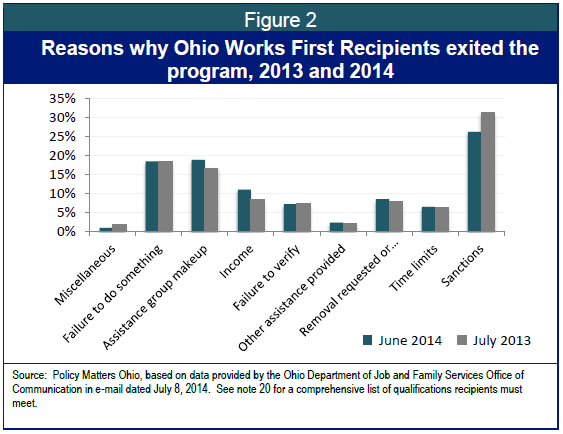

Program policies contributed to the decline in Ohio Works First caseload even as deep poverty increased. For example, Ohio’s cash assistance program has a shorter time period for support (36 months) than federal requirements (60 months). Some families ran out of months during the slow recovery from the recession. In addition, as shown in Figure 2, program tracking demonstrates that Ohio ‘sanctioned’ or removed more than a quarter of enrollees for failure to succeed at work requirements (self-sufficiency contract).[20]

Food aid: Nearly 2 million low-income Ohioans saw food assistance cut when the federal government’s temporary boost to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) expired in November of 2013. Food aid through SNAP averaged about $1.40 per person per meal after the cut. For a family of three, the reduction, on average, cost $29 a month.[21] At the same time, the federal government offered Ohio a statewide waiver of the work requirement for adults without children because the sluggish economy made it hard for people to find work, but Ohio refused the waiver for 72 of 88 counties.[22]

Childcare: Initial eligibility in the state’s public childcare assistance program was reduced from 150 percent of poverty to 125 percent of poverty in the budget for fiscal years 2012-13.[23] Today, in spite of rising poverty, eligibility is far below that, at $19,790 for a family of three. Ohio has one of the lowest eligibility rates in the nation.[24]

Health care: Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act was enacted in Ohio through the Controlling Board when the General Assembly failed to expand it through the budget bill. As a result of Medicaid expansion, hundreds of thousands of Ohioans can now control chronic diseases, get treatment for cancer or injuries, and live healthier, more productive lives. The federal government pays for those who signed up as a result of the expansion.

Self-sufficiency levels for families in Ohio

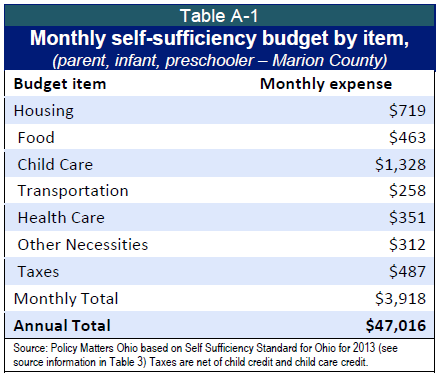

The cost of self-sufficiency for a family of three (a working parent, an infant and a preschooler) can be more than twice the poverty level, or even 2.5 times the poverty level, depending on location. Table 2 illustrates the income needed for self-sufficiency in different counties in Ohio.

The self-sufficiency budget includes housing, food, childcare, transportation (including to work), health care, other necessities and taxes. An illustration of the elements of the self-sufficient family budget for a three-person family is given in the Appendix in Table A-1.

Wages of Ohio’s largest occupational categories

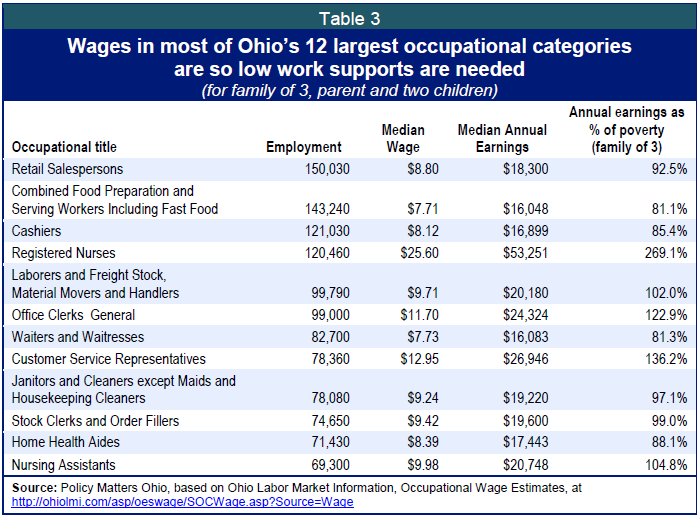

Of the 12 largest occupational categories in Ohio, just one pays a wage that allows self-sufficiency for a family with a single parent and two children earning a median annual wage (Table 3).

Public assistance helps low-wage taxpayers retain jobs and low-income employers retain a stable workforce. For example, of Ohio’s 75,000 frontline fast-food workers, 45 percent are forced to turn to one of several public benefit programs for their families: 39 percent to the Earned Income Tax Credit, 17 percent to Medicaid, 13 percent to the Children’s Health Insurance Program and 21 percent to food stamps. For these Ohio fast-food workers, the combined public cost of these programs is $291 million: $40 million for food stamps, $67 million for the federal EITC, $132 million for adult Medicaid and $48 million for children’s health insurance.[25]

The cost of self-sufficiency is far higher than the wages widely available for the workforce in Ohio.

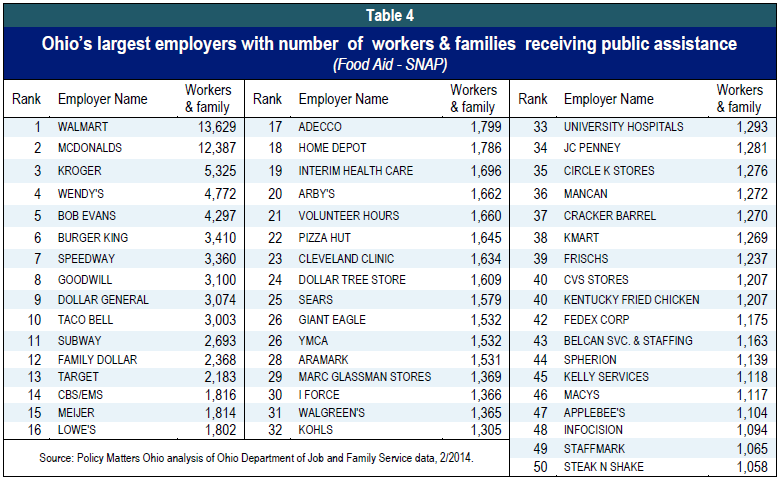

The list of Ohio’s 50 largest employers (Table 4), and the number of their employees and family members receiving food aid, illustrates the broad range of employer types and sectors in which wages just don’t make ends meet. The costs of living that wages do not cover for these employees are shifted from the employer to the public sector.

Conclusion

The five initiatives in House Bill 483 focus on getting people off of public assistance and into jobs. They are to restructure incentives for caseworkers and departments to make exiting assistance a larger goal. This presumes that there is currently insufficient incentive to work, but several facts call that presumption into question. First, poverty is a terrible hardship. Families must be so poor to qualify for cash assistance, in particular, that it is hard to imagine they would not prefer another alternative. Second, there are already work requirements or time limits for many forms of aid. Third, the largest category of those leaving cash assistance do so because they can’t succeed at work – presumably the reason they sought aid in the first place.

There are flaws in our labor market and harsh policies in some of our safety net programs. Ohio’s largest job categories are too low-wage for families to meet basic needs without continued help. Unemployment was high enough for Ohio to qualify for a waiver of some federal rules restricting food aid, but this administration turned the waiver down. Our eligibility for help with childcare assistance is among the lowest in the nation.

If the result of the recommendations of the MBR initiatives is that families leave assistance and get jobs that fully meet needs, that would of course be excellent. But the track record in Ohio makes that outcome seem elusive – we have too few good jobs, and we are too quick to slash the safety net that helps families survive in this economy.

APPENDIX

[1] Testimony of Jack Frech, Director of Athens County Job and Family Services Department, before the House Aging and Health Committee, 130th Ohio General Assembly, April 2, 2014 at http://www.ohiohouse.gov/committee/health-and-aging

[2] Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, Business Information Channel (BIC) data, “OWF – State Jan 2011 – present,” provided by Athens County Job and Family Service Director Jack Frech in an e-mail dated June 10, 2014.

[3] Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, Business Information Channel (BIC) data, “Work Activity: All Family work participation rate, July 2012-present,” provided by Athens County Job and Family Service Director Jack Frech in an e-mail dated June 10, 2014.

[4] Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, “Ohio Works First” at http://jfs.ohio.gov/factsheets/owf.pdf

[5] An estimated 85.5 percent of American households were food secure throughout the entire year in 2012, meaning that they had access at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life for all household members. The remaining households (14.5 percent) were food insecure at least some time during the year, including 5.7 percent with very low food security—meaning that the food intake of one or more household members was reduced and their eating patterns were disrupted at times during the year because the household lacked money and other resources for food.

Alisha Coleman-Jensen Mark Nord Anita Singh, “Household food insecurity in the United States, 2012, September 2013, Table 4, p.19 and Table 5, p.20, at http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err155.aspx#.U63KlBYk_1p

[6]E-mail from the ODJFS Office of Communications, June 8, 2014.

[7] United States Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program – Eligibility” at http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/eligibility

[8] Id.

[9] Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, Public Assistance Monthly Statistics (Table 3) at http://jfs.ohio.gov/pams/index.stm

[10] Ohio Department of Medicaid, Caseload Report for June 2014, “Actual versus estimated eligible, SFY 2014,” at http://medicaid.ohio.gov/Portals/0/Resources/Reports/Caseload/2014/06-Caseload.pdf

[11] Health Policy Institute of Ohio, “Ohio Medicaid Basics 2013” at http://a5e8c023c8899218225edfa4b02e4d9734e01a28.gripelements.com/pdf/publications/medicaidbasics2013_final.pdf

[12] Child Care and Development Fund Plan for Ohio: FFY 2014-15 at http://jfs.ohio.gov/cdc/docs/FY20142015StatePlanDRAFTFINAL.stm; note that families that have been enrolled in Ohio Works First have slightly different program eligibility standards.

[13] E-mailed communication from the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, April 10, 2014.

[14] Wendy Patton, “Ohio’s Childcare Cliffs, Canyons and Cracks,” May 2014 at http://www.policymattersohio.org/childcare-may2014

[15] Alemayehu Bishaw, “Poverty: 2000 to 2012,” American Community Survey Briefs, United States Bureau of the Census, September 2013 at http://www.ohio.com/polopoly_fs/1.430049.1379557156!/menu/standard/file/poverty.pdf

[16] This is part time work, but some sectors do not offer what we traditionally consider full-time work of 40 hours per week. In June in 2014, for example, the average weekly hours in leisure and hospitality industries was 26.1 hours; in retail, it was 31.8 hours, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (Table B-2 at http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t18.htm). Erratic hours in low-wage sectors make it difficult for workers to hold several jobs, with hours that shift every week.

[17] Bishaw, Op.Cit., Table 3: Number and Percentage of People With Income-to-Poverty Ratio Below 50 Percent by State: 2000 and 2012, p.7. According to this table, Ohio ranks 16th among the states in share of people living at or below 50 percent of the poverty line.

[18] Kids Count Data Center (Annie E. Casey Foundation) at http://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/Line/45-children-in-extreme-poverty-50-percent-poverty?loc=1&loct=2#2/37/false/868,867,133,38,35,18,17/asc/any/326

[19] Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, Business Information Channel (BIC) data, Op.Cit.

[20] In July of 2013, 31 percent of exits from Ohio Works First were attributed to sanction; this had declined to 26 percent in June of 2014 (e-mail from ODJFS Office of Communications, July 8, 2014). According to the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, category definitions include: Failure to do "something" - Failure to complete interview, cooperate in the reapplication process, return interim report, sign an application, etc.; Assistance Group Makeup - No eligible children in assistance group; children placed in foster care; children currently on another assistance case; etc.; Income - Income exceeds program eligibility standards; Failure to Verify - Identity, income and/or residency have not been verified; Other Assistance Provided - Approved for another category of assistance; Removal requested or moved - Removal requested verbally or in writing; application withdrawn; Time Limits - 36 months are exhausted; good cause extension denied; "hardship extension" denied or terminated; Sanctions - Failure to comply with self sufficiency contract; Miscellaneous - Other rarely used denial codes. Provided via e-mail form the Ohio Department of Job and Family Service Office of Communications, November 13, 2013.

[21] Wendy Patton, “Low Income Ohioans Face Food Assistance Cut in November,” Policy Matters Ohio, October 2013 at http://www.policymattersohio.org/snap-oct2013

[22] Marilyn Miller, “Rules Changing for some able-bodied adults to receive food stamps, Akron Beacon Journal (Ohio.com) October 4, 2013 at http://www.ohio.com/news/local/rules-changing-for-some-able-bodied-adults-to-receive-food-stamps-1.434090

[23] Eligibility dropped from 200% of poverty in 2009. Legislative Service Commission, Redbook for Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, FY 2012-13 budget at http://www.lsc.state.oh.us/fiscal/redbooks129/jfs.pdf, p.158.

[24] National Center for Children in Poverty, State Profile at http://bit.ly/VmH6Rg. See National Women’s Law Center, “Pivot Point: State Childcare Assistance Policies 2013,” http://bit.ly/1rrqyFj - See more at: http://www.policymattersohio.org/childcare-may2014#sthash.HdpCIYm2.dpuf

[25] Sylvia Allegretto, Marc Doussard, Dave Graham-Squire, Ken Jacobs, Dan Thompson and Jeremy Thompson, “Fast Food, Poverty Wages: The public cost of low wage jobs in the fast-food industry,” UC Berkeley Labor Center and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, October 2013 at http://www.policymattersohio.org/fast-food-oct2013

Tags

2014Revenue & BudgetWendy PattonPhoto Gallery

1 of 22