Cuts and Breaks

July 02, 2014

Cuts and Breaks

July 02, 2014

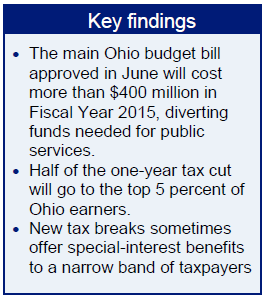

Most of the $400 million-plus in tax cuts for Fiscal Year 2015 will go the affluent. The Mid-Biennium Review also continues with an unfortunate Ohio tradition of permitting or enlarging tax benefits to special, narrow groups of taxpayers.

Download Summary (2pp)Download report (10pp)Press release

Tax Changes in the Mid-Biennium Review

The main budget bill approved by the Ohio General Assembly earlier in June will cut taxes in the next budget year by more than $400 million. Gov. John Kasich signed House Bill 483 into law at a food bank and proclaimed, “We are focusing the tax benefit on the people who are at the lowest income level."[1] In fact, the lowest-income Ohioans will see an average tax reduction for 2014 of just $4. Middle-income Ohioans also will gain only modestly. At the same time, half of the one-year tax cut will go to the top 5 percent of Ohio earners., and the top 1 percent, who will get nearly a third of it, will average more than $1,800 each.

The main budget bill approved by the Ohio General Assembly earlier in June will cut taxes in the next budget year by more than $400 million. Gov. John Kasich signed House Bill 483 into law at a food bank and proclaimed, “We are focusing the tax benefit on the people who are at the lowest income level."[1] In fact, the lowest-income Ohioans will see an average tax reduction for 2014 of just $4. Middle-income Ohioans also will gain only modestly. At the same time, half of the one-year tax cut will go to the top 5 percent of Ohio earners., and the top 1 percent, who will get nearly a third of it, will average more than $1,800 each.

The $400 million instead could be used to address Ohio’s many needs. Deaths among the youngest Ohioans – our infants – remain shockingly high. Our cities are pocked with vacant and abandoned properties, casualties of the foreclosure crisis. Coalitions in the state’s biggest cities are rallying to expand support for preschool. These are just a few of the major needs that are going unmet.[2]

This brief outlines the key tax changes in the main budget bill, as well as some of those in a companion measure, House Bill 492, that grew out of Gov. Kasich’s original Mid-Biennium Review (MBR) proposal last March. Apart from four well-publicized changes that will cut income taxes, there are also new tax breaks that, while usually modest in size, sometimes offer special-interest benefits to a narrow band of taxpayers. These include:

- Revised tax breaks that allow investors to more easily receive tax credits for investments in small companies, which merely have to keep paying existing employees for investors to qualify;

- Allowing a particular company to apply for a local property tax break that until now, according to state rulings, had not met technical requirements;

- Temporarily allowing an estimated $39 million in previously awarded historic-preservation tax credits to be taken against the Commercial Activity Tax, which investors otherwise would not have been able to use because of changes in tax law; and

- Expanding a recently approved property-tax break so it likely covers the Moose fraternal organization.

The four income-tax cut provisions will:

- Accelerate the last piece of an across-the-board, 10 percent income-tax cut approved last year, so that the final 1 percent reduction scheduled to take place in calendar year 2015 will instead take place this year;

- Temporarily add to a tax break for business income that goes to anyone who shares in the profit of a partnership or other entity whose income passes through to its owners. This deduction, first created a year ago, is being increased for this year to 75 percent of the first $250,000 in such income (it was 50 percent);

- Increase personal exemptions under the income tax. Taxpayers with Ohio adjusted gross income of $40,000 or less will see their exemptions increase from $1,700 to $2,200 starting in tax year 2014; those with income over $40,000 but less than or equal to $80,000 will see an increase to $1,950,[3] and

- Boost Ohio’s state Earned Income Tax Credit, first approved last year, to 10 percent from the current 5 percent of the federal credit. However, unlike the federal credit, this state income-tax credit will remain nonrefundable and capped, so that most of Ohio’s poorest earners would see very little gain from the change.[4]

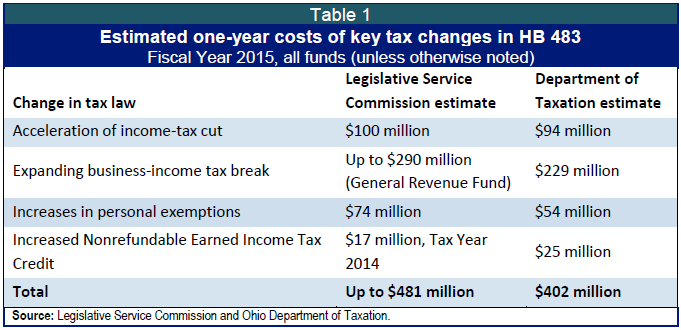

As detailed below in Table 1, the four changes will cost more than $400 million in Fiscal Year 2015. Though the measure as passed makes the expanded business deduction contingent on the state having the funds available, this is highly likely. Table 1 shows estimates by the Legislative Service Commission (LSC) and the Kasich administration, respectively, for the impact of each of these changes. Figures are for Fiscal Year 2015, unless otherwise noted.

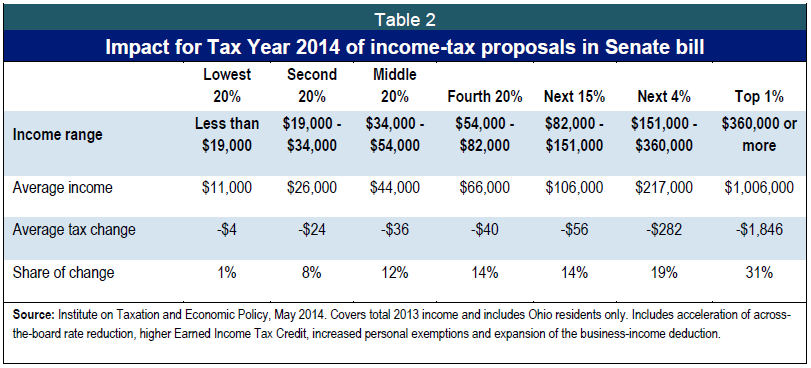

Low- and middle-income Ohioans pay more as a share of their incomes in state and local taxes than upper-income Ohioans do.[5] That’s because sales, excise and property taxes fall more heavily on the less affluent. By contrast, Ohio’s progressive income tax increases as income rises, making it the state’s only major tax that is based on the ability to pay. Cutting the income tax provides little or no benefit to the poorest Ohioans because while they pay significant amounts of other taxes, they don’t have much income-tax liability. And while middle-income residents get some benefit from the two permanent income-tax cuts, increasing the EITC and boosting personal exemptions, it is quite limited. The average 2014 savings for Ohio residents in the middle 20 percent of the earnings spectrum is just $36 on average (see Table 2 below).

Recent Ohio tax cuts have not been shown to create jobs. The legislature passed a tax-cut package in June 2013, including income-tax rate reductions and the business-owner tax break; since then, Ohio has gained 43,100 jobs. This 0.8 percent increase compares with a state job gain of 66,300, or 1.3 percent, in the 11 months before the tax break was approved, and a 1.5 percent gain during 2012. Between June 2013 and May 2014, the number of jobs in the United States grew by 1.6 percent, nearly twice as strong as Ohio’s growth. There has been no surge in Ohio job creation since this tax break and the rate cut were approved. Since 2005, when legislators slashed income-tax rates and eliminated Ohio’s corporate income tax, Ohio has lost jobs, though the nation has gained them. While the state unemployment rate has fallen from its peak, a large part of the decline reflects the drop-out of more than 100,000 Ohioans from the labor force. These workers are no longer officially counted as unemployed.

By far the largest component of the tax cuts for Fiscal Year 2015 in House Bill 483, as shown in Table 1, is the temporary expansion of the income-tax deduction for business income. While this has been billed as a job creation measure, the vast majority of those who can take advantage of it do not employ anyone and are unlikely to do so.[6] Many are self-employed, earn side income from other jobs, or are passive investors. Though overnight this tax deduction became one of the biggest breaks in Ohio’s tax code, it is spread among hundreds of thousands of owners who have averaged just $731 in annual tax benefits apiece so far.[7] It’s no surprise that that isn’t generating much job growth.

Like other income-tax cuts, the latest batch favors the wealthiest Ohioans. An analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, a nonprofit research group with a model of the tax system, found that overall, half of the tax cut this year will go to the 5 percent of Ohioans with incomes over $151,000 a year. The top 1 percent of Ohioans, who had incomes of at least $360,000 last year, will receive an average tax cut of $1,846. The middle fifth, who made between $34,000 and $54,000, will see an average tax cut of just $36.

Though the tax package includes an expansion of the state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a positive step, this does little for the poorest Ohioans.[8] Overall, the bottom fifth, who make less than $19,000, will get just 1 percent of the tax benefits from the package, or an average of just $4. Table 2 provides a breakdown of the average effect of the four changes on taxes to be paid on 2014 income:[9]

Tax Breaks

House Bill 483 and House Bill 492, another bill that originated in Governor Kasich’s MBR proposal and was just signed into law, both contain other tax provisions. Some make changes that may ease tax administration. But while they do not have the same consequences for the amount of tax revenue the state receives, both set out tax policy and in some instances provide special tax breaks to individual companies or investors. Among the provisions of these bills are the following:

House Bill 492

Loosened requirements for an existing investment tax credit. HB 492 includes a proposed change in the InvestOhio personal income-tax credit.[10] Under this credit, investors can receive a 10 percent income-tax credit for investing in qualified small companies with Ohio operations and holding onto the investment for at least five years. The bill reduces the holding requirement to two years. Currently, this program does not include a requirement that those companies create any new jobs. Investors are eligible for the credit if the companies they invest in simply pay to their existing employees an amount equal to the investment received (This is one of a number of different ways the small business can invest the cash for investors to qualify. See Ohio Revised Code, Section 122.86(1)(d)). This loophole should be closed. Investors should not receive tax credits – money that otherwise could be used for needed public investments – for investing in companies that simply continue to pay existing employees.

Hitachi Medical Systems America Inc. is allowed to apply for a retroactive Enterprise Zone tax abatement for its property in Twinsburg, which had been the subject of a case the company had appealed to the Ohio Supreme Court. Hitachi’s application had been denied by Tax Commissioner Joseph W. Testa because the application was made by Hitachi while the property was owned by a separate entity, HMSA Properties LLC. Testa ruled, and the Board of Tax Appeals upheld, that under Ohio law, only an owner can apply for exemption, so he did not have jurisdiction to consider the application. While this might be merely a formality, since HMSA is wholly owned by Hitachi, which is HMSA’s agent, and they share the same address, telephone and fax numbers, it was one that was taken seriously by the tax authorities. The case has been stayed for mediation, and under the bill, the property owner may apply for an exemption, including any unpaid taxes, penalties and interest that arose because it wasn’t exempted.

This provision was tailored to benefit Hitachi, but like similar tax measures designed at the behest of specific firms, there is no way to know that by reading the bill itself. The bill says it covers "an enterprise zone agreement entered into under section 5709.63 of the Revised Code by the record owner of qualified property and the board of county commissioners of a county having a population greater than five hundred thousand but less than six hundred thousand with the consent of a municipal corporation having a population greater than fifteen thousand but less than twenty thousand. For the purposes of this section, population is determined by reference to the 2010 decennial census.”[11] The LSC in its fiscal note on the bill notes that the property could include Tallmadge or Twinsburg in Summit County, or Springboro or Vandalia in Montgomery County.[12] This provision underlines that Ohioans should be able to find out easily who is benefiting from proposed changes in the tax code.

The basis was changed for collecting what is now called the Petroleum Activity Tax, so that it is based on an average price-per-gallon index and the number of gallons first sold in Ohio by a taxpayer, instead of on each taxpayer’s actual gross receipts. This tax, previously called the Motor Fuel Receipts Tax, was created last year by the General Assembly after the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that Commercial Activity Tax receipts on motor fuel had to be used for highway purposes. The LSC estimated that the change in the definition of gross receipts would cost $6.2 million in revenue a year, most of which would have gone to the Highway Operating Fund of the Department of Transportation.[13] The administration estimates the cost at $2 million.[14]

Job creation tax credits that had previously been awarded to companies for use against the Commercial Activity Tax may be used against the Petroleum Activity Tax to the extent the taxpayer couldn’t claim the full amount against the CAT. The Taxation Department estimated the cost of this shift at $9.8 million.[15] That’s the amount this is expected to reduce credits taken against the CAT and increase them on the PAT.[16]

HB 492 also made some other changes that tightened up on tax credit programs. It allows the director of the Development Services Agency (DSA) to reduce a research and development loan tax credit if the loan recipient fails to comply with requirements specified in the loan agreement. And job creation tax credits, one of the state’s economic development incentives, are likely to produce a smaller benefit during the first year they take effect. That’s because the bill eliminates the previous practice of computing the credit based on the employer’s increase in income-tax withholdings during just part of the year. Though it noted that this change was likely to reduce the amount of first-year credits, the LSC did not estimate the amount.[17] The bill also authorizes the taxation department to disclose information to the DSA to evaluate potential credits, grants and loans.[18]

House Bill 483

House Bill 483 expands a property-tax exemption approved in the last budget covering fraternal organizations such as the Masons, which provide financial support for charitable purposes. It reduces from 100 to 85 the number of years an organization has to have been operating in the state with a state governing body. The LSC noted that, “The Moose fraternal organization, the state governing body of which was founded in 1928, would likely benefit from this change.”[19] Other fraternal organizations may benefit, it added. The LSC estimated that state-wide, the provision would reduce local property taxes by “very roughly” $1 million (the taxation department estimated the impact would be minimal, and also said it was unaware of any other fraternal organizations that might benefit).[20] Now that this tax break has been extended to cover not only the Masons but the Moose, other organizations can be expected to seek further reductions in the time requirement so they, too, can qualify.

The bill allows investors to temporarily take the historic preservation tax credit against the state’s main business tax, the Commercial Activity Tax, which has not been among the taxes for which this credit could be used. That was one of two provisions in the bill involving this program, a refundable tax credit that can be used by investors to receive a tax credit of up to 25 percent of qualified expenditures for rehabilitating a historic building. Credits are evaluated and approved by the director of the Development Services Agency and are limited to $5 million.[21] This measure was opposed by the Ohio Manufacturers Association, much as it and a number of other business groups have opposed a number of proposed CAT credits and exclusions out of concern that such measures erode the base of the tax.[22]

According to the Ohio Department of Taxation, the provision will benefit a variety of taxpayers that, without this provision in the law, would not have been able to use historic preservation tax credits that they had previously been awarded.[23] For instance, this includes some investors that previously paid the corporate franchise tax, a tax that has been repealed, and did not have a place to claim historic-preservation credits they had expected to use. It also covers certain taxpayers who had previously paid the Dealers in Intangibles (DIT) Tax, a tax on mortgage and securities brokers, finance companies and others that was eliminated recently and replaced for some with another, new tax on financial institutions. Some of these former DIT taxpayers instead are paying the CAT, and as a result, were unable to apply historic preservation tax credits they had received.[24] Altogether, the taxation department estimates the cost of this shift at $39 million in Fiscal Year 2015, with some residual the following fiscal year.

The provision also allows some other investors in historic preservation projects, or in nonprofits that may have received the tax credits, to continue benefiting from the tax break though they do not pay the Commercial Activity Tax. Under the bill, someone who gets a historic preservation tax credit but is not a CAT taxpayer is allowed to file a CAT return for the purpose of claiming the credit (permitting certain businesses with less than $150,000 in annual gross receipts to claim the credit though they don’t pay the CAT). In essence, as the taxation department explains, the legislation “makes the CAT the place where different taxpayers can go to claim the historic credit if they have no other place to claim it.” It is unknown who might benefit from this provision; the $39 million cost was estimated from individual company tax returns and therefore is confidential.[25]

The bill also allows one tax credit each biennium worth up to $25 million to go to a person whose rehabilitation of an historic building qualifies as a "catalytic project." This is defined as “an historic building, the rehabilitation of which will foster economic development within two thousand five hundred feet of the historic building.”[26] This might support the project to turn the old May Co. department store building in downtown Cleveland into apartments, which already has won $5 million in such credits.[27] The bill does not change the $60 million annual maximum of historic preservation credits, and restricts claims for the catalytic credit to increments of $5 million a year. It also mandates that the owner spend more than $75 million on qualified rehabilitation expenditures for the catalytic project.

Among the other provisions of the bill are tax changes including:

A property tax break for an organ and blood donation organization. House Bill 483 exempts from taxation real property of a charitable organization that is used exclusively by the organization for receiving, processing, distributing, researching, or developing human blood, tissues, eyes or organs. This will affect one entity, according to the taxation department.[28]

Additions in the authorized uses of revenue from Tax Incentive Financing. The law authorizes political subdivisions to use revenue collected from Tax Increment Financing to fund the provision of gas or electric service through privately owned facilities if that is necessary for economic development. Previously, such payments could be used for public infrastructure improvements specified in the ordinance approving the TIF, including provision of gas or electric service, but the law did not expressly allow that through privately owned facilities.

Remission of sales tax based on prearranged agreement. Under the previous law, food service vendors could voluntarily agree to a test check, under which the taxation department would send someone to the outlet and keep track for a period of how much of its sales were taxable. Then, rather than having to keep track of every sale, the vendor could agree to pay tax on that percentage of its total sales. Under the new law, some other means of determining taxable sales, which has to be developed, will be created as another alternative. The law also eliminates the requirement that the tax commissioner find that the vendor’s business is such that maintenance of complete records of all sales would impose an unreasonable burden. The commissioner or the vendor can terminate the agreement if either finds that the nature of the vendor’s business has changed and the proportion of sales that is taxable under it is no longer representative.

Stadium maintenance and improvement in Stark County. Stark County and its convention and visitors’ bureau will be allowed to use up to $500,000 a year in revenues from the existing lodging tax to improve and maintain a stadium there, in cooperation with other parties.

Recovery of local government tax refunds. The taxation department collects certain taxes and fees for local governments. When a taxpayer gets a refund, the department pays the refund from the state Tax Refund Fund and then withholds that amount from its next distribution to the local government. Under previous law, if the refund exceeded 25 percent of a local government’s next distribution, the department could spread the recovery of the refund over multiple distributions over the next 24 months. That period has now been increased to 36 months, which the LSC notes could result in higher distributions of tax revenue to certain local governments during the next two years.[29]

Conclusion

The tax changes approved in the Mid-Biennium Review will siphon more than $400 million this fiscal year into tax cuts. Most of this will go to affluent Ohioans. This is unlikely to boost Ohio jobs, based on past experience. The MBR also continues with an unfortunate Ohio tradition of permitting or enlarging tax benefits to special, narrow groups of taxpayers. We should review the tax breaks we have now, as legislators on both sides of the aisle have proposed.[30] Instead of more tax cuts, we should restore and expand funding to local governments, public schools, health and human services and post-secondary education. This approach would improve communities, build opportunities for children and create the needed infrastructure for businesses.

[1] Kovac, Marc, “Kasich signs mid-biennium budget bills,” The Alliance Review, June 17, 2014, at http://www.the-review.com/dix%20statehouse/2014/06/17/kasich-signs-mid-biennium-budget-bills.

[2] The budget bill included an additional $10 million for services that protect the elderly from abuse and neglect, and a similar amount for child protective services, as well as $16 million for child care subsidies. These are needed improvements. But they do not substitute for the large-scale investments in education, infrastructure and human services that Ohio badly needs. See Wendy Patton, “Mid-Biennium Review Should Focus on Investments, Not Tax Cuts,” Policy Matters Ohio, Apr. 1, 2014, at www.policymattersohio.org/mbr-apr2014.

[3] Gov. Kasich earlier this year proposed increases in the personal exemption for these two groups. His proposal called for larger increases – to $2,700 and $2,200, respectively.

[4] Most state EITCs also are refundable. This means that a tax filer gets a refund if the credit exceeds their income-tax liability.

[5] “Ohio State and Local Taxes Hit Poor and Middle Class Much Harder than Wealthy,” Policy Matters Ohio, Jan. 30, 2013, at http://www.policymattersohio.org/income-tax-jan2013. That analysis from January 2013 does not include the tax changes approved by the General Assembly last year, which primarily benefited the top income earners in the state and exacerbated this fundamental inequality. See Patton, Wendy, Zach Schiller and Piet van Lier, “Overview: Ohio’s 2014-2015 Budget,” Policy Matters Ohio, Oct. 3, 2013, Table 1, p. 5, at www.policymattersohio.org/budget-oct2013.

[6] See Zach Schiller, “Tax Break for Business Owners Won’t Help Ohio Economy,” Policy Matters Ohio, Apr. 2, 2013, at www.policymattersohio.org/tax-breakpr-apr2013. A recent national study by researchers at the U.S. Treasury Department found that only 11 percent of taxpayers reporting business income – and 2.7 percent of all income-tax payers – own a bona fide small business with employees other than the owner. See Matthew Knittel, Susan Nelson, Jason DeBacker, John Kitchen, James Pearce, and Richard Prisinzano, “Methodology to Identify Small Businesses and Their Owners,” Office of Tax Analysis, U.S. Department of Treasury, August 2011, Table 8, at http://1.usa.gov/1kbDNoT.

[7] That average reflects those taxpayers that had claimed the deduction by mid-May; taxpayers will continue filing extensions through Oct. 15. Conversation with Gary Gudmundson, Ohio Department of Taxation, May 20, 2014.

[8] For more details on how the expanded EITC will affect Ohioans, see Zach Schiller and Hannah Halbert, “Flawed Tax Cuts in Senate Budget Bill,” Policy Matters Ohio, May 27, 2014, Table 4, at http://www.policymattersohio.org/senate-budget-may2014. The poorest Ohioans would see almost no benefit at all; the increase in the tax credit would be so small that it would round to no change in the average tax. Only 1 percent of the total increase in the credit would go to the fifth of Ohioans who made less than $19,000 last year, and even among the small number who benefited, the average increase in the size of their credit would be just $6 a year.

[9] Ibid. For a more detailed breakdown of the other components of the tax changes, see Table 3.

[10] The director of the Ohio Development Services Agency is authorized to award up to $100 million in such tax credits during the current two-year state budget, which ends on June 30, 2015. As described by the agency, “InvestOhio is a new tool to provide much needed capital into Ohio's small businesses, helping them create jobs.” See Ohio Development Services Agency, InvestOhio Program, at https://development.ohio.gov/bs/bs_investohio.htm.

[11] House Bill 492, As Enrolled, at http://www.legislature.state.oh.us/bills.cfm?ID=130_HB_492.

[12] Ridzwan, Ruhaiza, Legislative Service Commission, Fiscal Note & Local Impact Statement, Am.Sub. H.B. 492 of the 130th General Assembly, As Enacted, June 3, 2014, p. 9, at http://www.lsc.state.oh.us/fiscal/fiscalnotes/130ga/hb0492en.pdf.

[13] Ibid, p. 8.

[14] Email from Gary Gudmundson, Ohio Department of Taxation, June 18, 2014

[15] Ibid.

[16] This wouldn’t change the overall cost of the credit, but would shift the impact among different state funds.

[17] Op. cit., Legislative Service Commission Fiscal Note on Am. Sub. H.B. 492, p. 5.

[18] Tax Commissioner Testa told the publication Tax Analysts that the taxation department and the DSA had had an informal agreement since 2012 to review the tax status of a company that applies for credits, but that HB 492 would streamline the process. Koklanaris, Maria, “Ohio Bill to Make Tax Credit Process More Transparent Goes to Governor,” Tax Analysts, June 5, 2014.

[19] Legislative Service Commission, Comparative Document (Including Both Language and Appropriation Changes) House Bill 483, 130th General Assembly, Appropriations/Mid-Biennium Review (FY 2014/FY2015), As Enacted, June 17, 2014, p. 224, at http://www.lsc.state.oh.us/fiscal/mbr130/comparedoc-hb483-en.pdf

[20] Ibid, p. 224, and email from Gary Gudmundson, Ohio Department of Taxation, June 18, 2014

[21] Though the credit is capped at $5 million, in any one year, the refund cannot exceed $3 million, and the rest can be carried over for up to five years.

[22] Ohio Manufacturers’ Association, “Get the CAT Credit for Rehab of Historic Buildings Out of Bill,” Apr. 4, 2014. OMA Chairman Eric Burkland’s letter to House Speaker Bill Batchelder and Senate President Keith Faber is at http://www.ohiomfg.com/wp-content/uploads/2014-04-04_lb_tax_OMA.CAT_.Leadership.3.26.2014.pdf.

[23] E-mails from Gary Gudmundson, Ohio Department of Taxation, June 18 and June 20, 2014.

[24] One interesting irony is that some of these former DIT taxpayers benefited when that tax was eliminated. They were allowed to pay the CAT, instead of shifting over to pay a newly created tax on financial institutions, which would have cost them more. The taxation department says that these former DIT taxpayers aren’t the major beneficiaries among the variety that will be able to claim the credit temporarily against the CAT. However, for that small number who are benefiting from the latest change in the historic preservation credit, it means their tax break is being protected on top of the tax cuts they received.

[25] E-mail from Gary Gudmundson, Ohio Department of Taxation, June 24, 2014

[26] House Bill 483, As Enrolled, Section 149.311, at http://www.legislature.state.oh.us/bills.cfm?ID=130_HB_483. The project also has to meet all the existing requirements for the credit. In deciding whether a project qualifies as catalytic, the development services director also has to consider the number of jobs the project will create and the effect that issuing the credit would have on the availability of credits for other applicants, given the $60 million annual cap.

[27] Jarboe McFee, Michelle, “May Co. apartment plans could benefit from “catalytic project” change to Ohio tax-credit program,” The Plain Dealer, June 25, 2014, at http://www.cleveland.com/business/index.ssf/2014/06/may_co_apartment_revamp_could.html#incart_river and “May Co., Worthington apartment plans in downtown Cleveland among top winners of state tax credits,” The Plain Dealer, Dec. 20, 2013, at http://www.cleveland.com/business/index.ssf/2013/12/may_co_worthington_redevelopme.html.

[28] E-mail from Gary Gudmundson, Ohio Department of Taxation, June 18, 2014

[29] Legislative Service Commission, Comparative Document, op. cit., p. 234.

[30] See House Bill 24 by Rep. Terry Boose, R-Norwalk, and House Bill 81, by Reps. Mike Foley, D-Cleveland, and Denise Driehaus, D-Cincinnati. Both bills would require a regular review of tax exemptions, credits and deductions. The bills differ on certain points, such as how often: HB 24 calls for a review every eight years, while HB 81 would require one every two years.

Tags

2014Revenue & BudgetTax ExpendituresTax PolicyZach SchillerPhoto Gallery

1 of 22