Frack tax testimony: Raise tax rates, trim breaks to strengthen HB 375

January 15, 2014

Frack tax testimony: Raise tax rates, trim breaks to strengthen HB 375

January 15, 2014

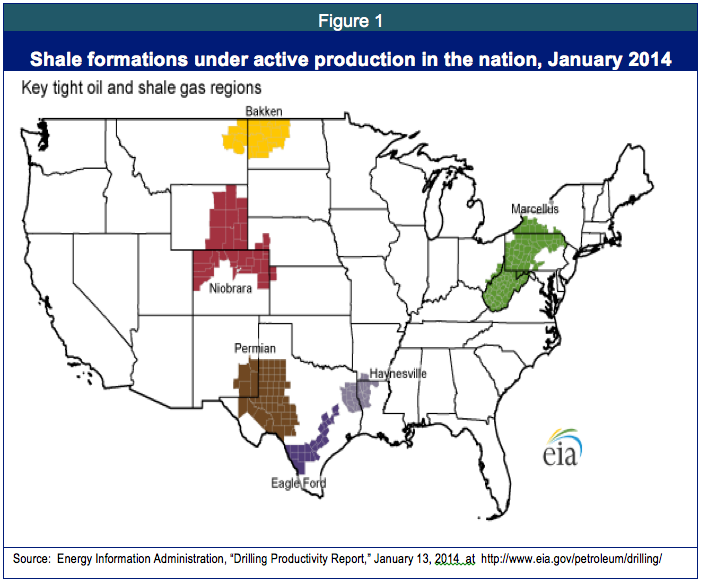

Download testimony (6 pp)Response to request for information (2 pp)Updated Jan. 23, 2014House Bill 375 undersells a valuable Ohio resource and needs to be strengthened. We support legislative efforts to develop a structure more in line with the growing industry in our state.

Testimony to the House Ways and Means Committee

Good afternoon Chairman Beck and members of the committee. I am Wendy Patton, Senior Project Director at Policy Matters Ohio, a not-for-profit, non-partisan research organization with a mission of contributing to a more prosperous, equitable, inclusive and sustainable Ohio. Thank you for the opportunity to testify today on House Bill 375.

We support a stronger severance tax for the oil and gas industry and we support efforts of the legislature to develop a structure more in line with the growing industry in the state. But many provisions of House Bill 375 need to be strengthened or changed. In its current form, it undersells a valuable resource. We have eight recommendations for your consideration.

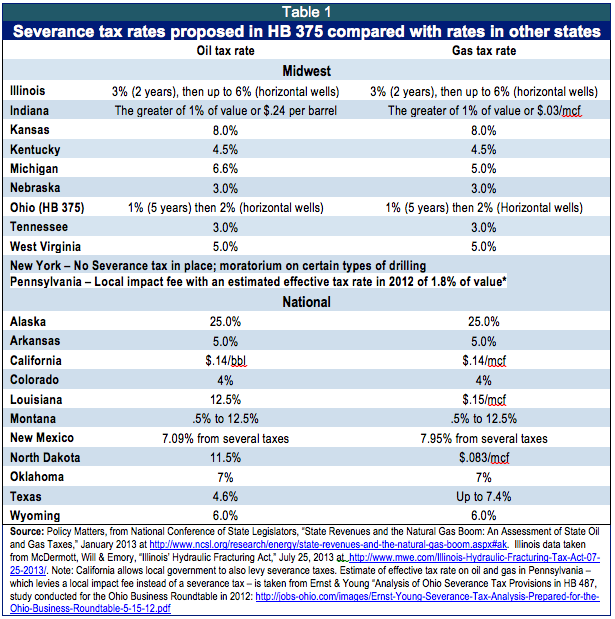

- Raise the tax rates. HB 375’s severance tax rates are lower than most oil- and gas-producing states, particularly states with active drilling in shale. They need to be higher, in line with other oil and gas producing states.

- Provide ODNR with funding necessary for mandated work. HB 375 reduces ODNR’s share of severance tax proceeds by reducing rates on some production and repealing the regulatory cost recovery assessment. The share of revenues for oversight, reclamation and mapping would be reduced even as the industry expands rapidly. The eventual cost of oversight of a boom in horizontal drilling may be higher than anticipated today.

- Trim and target tax breaks. HB 375 subsidizes the oil and gas industry through tax credits and exclusions, yet requires nothing in return. With its new severance tax, Illinois uses subsidy to benefit working families. The tax rate of 6 percent on natural gas is reduced by 0.25 percent for the life of the well when a minimum of 50 percent of the total workforce hours on the well site are performed by Illinois construction workers being paid wages equal to or exceeding the general prevailing rate of hourly wages. Subsidies and tax breaks should be rarely used, but when they are, they should incentivize specific behavior, like hiring Ohio workers rather than out-of-state work crews.

- Eliminate or narrow the cost recovery period. Horizontal drilling and well stimulation are high-cost, high-yield techniques used to get at the resources in Ohio’s shale formations. The industry won cost recovery tax holidays in other states in earlier years to help develop these new techniques, but the techniques are no longer experimental. As technology has evolved, the tax code should as well. Ohio does not need to adopt tax favors fought for by the oil and gas industry in other states and other decades. If it does, it should tie such breaks to garnering specific benefits for working families and communities where drilling is located.

- Eliminate the exclusion from the CAT. The exclusion of payers of the horizontal well severance tax from the state’s general business tax, the Commercial Activity Tax, is a special-interest carve-out. These kinds of carve-outs have been opposed by many to prevent the CAT from becoming so pocked with exclusions and breaks that rates must rise. The oil- and gas-production industry did not get special treatment under the corporation franchise tax, nor when the CAT originated. There is no reason for it to get such treatment now.

- Eliminate or narrow the income tax credit: This tax credit goes far beyond landowners with bad lease terms. It could be very costly. Auditing could be difficult: ownership interests may be finely parsed, widely dispersed, with widespread assignment of tax benefit.

- Base the severance tax on gross value instead of net proceeds. The language in HB 375 that defines "net proceeds" as allowing the exclusion of "any" post-production costs invites excessive deductions in a way that "gross value" does not. The language describes included costs, but not excluded costs.

Montana had a local oil and gas production tax based on net proceeds (but administered by the state). The oil and gas industry preferred the net proceeds tax as long as the Department of Revenue never audited the deductions. The Department audited the deductions more thoroughly beginning in the 1980s. The oil and gas industry then discovered that there were too many complexities and ambiguities involved in determining what deductions were allowable and too much uncertainty associated with appeals--so the law migrated to "gross value" as a simpler starting point.[1]

- Use proceeds of the severance tax to meet the needs of Ohioans. HB 375’s use of the severance tax revenue for income tax cuts results in a distribution that favors the wealthy. Policy Matters Ohio examined Gov. Kasich’s 2012 proposal to increase the severance tax and use the revenues for an income-tax cut, and found Ohio households in the middle quintile would see on average a yearly benefit of $42 in years that the income tax give-back fund is $500 million. Households in the top 1 percent would see $2,300 on average. HB 375 would require its own analysis – the numbers would be smaller – the basic pattern would be the same.

A severance tax more like that of other producing states will not stop development, if the resource is here. In 2010, West Virginia, with a severance tax rate of 5 percent on oil and gas, led the country in the number of new gas wells drilled. And, despite the lack of a severance tax, Pennsylvania drilled less than half (833) the number of new wells as West Virginia (1,896). In the late 1990s, Montana lowered production tax rates and added incentives for new production while Wyoming eliminated a severance tax reduction. As a result of the policy changes, the overall tax rate on the natural gas industry was 50 percent higher in Wyoming than in Montana. Both states subsequently underwent a boom in natural gas drilling, but Wyoming has fared better. Between 2000 and 2006, Wyoming added over $10 billion in production value, while Montana only added $2 billion.[2]

Ohio has used income tax cuts as an economic development strategy over the past eight years. Income tax rates have been reduced, or approved for reduction, of nearly 29 percent. But Ohio’s job creation has lagged that of the nation. Since the state income-tax cuts began in 2005, Ohio has ranked third worst among the states in job growth.[3]

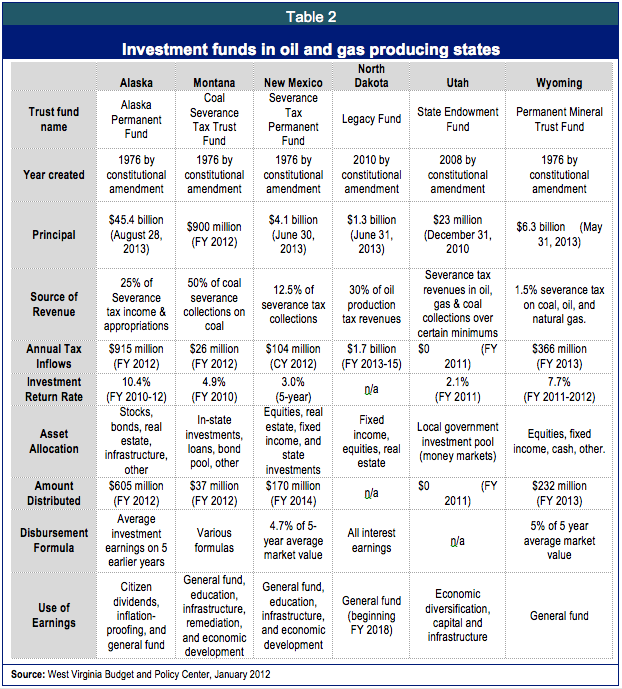

States and nations alike find new ways to compete through access to the internet, transportation networks, systems of higher education, and so forth. Investment takes resources. Legislators must identify and harness resources fairly and efficiently. The severance tax is a fair source for funds to build Ohio’s competitiveness for tomorrow, just as the growth industries of the twentieth century contributed to the development of the state as a powerful manufacturing region. It is a fair source to help impacted communities as well. Studies have found that communities that have funding to handle costs that rise in a natural resource boom do better in the long run, when the resource is gone, than other communities.[4] The attachment illustrates uses of severance tax revenues in several states.

Severance taxes are needed, and the revenue they generate should support proper oversight and regulation of the industry, mitigate impacts on local communities, meet current needs of the state and build diversity in the economy for after the boom is over.

Thank you, and I will be glad to answer your questions.

Response to request from Rep. Cera

Chairman Beck, Ranking Member Letson and members of the Ways & Means Committee:

Thanks again for the opportunity to testify before the committee on January 15, 2014 on House Bill 375. I am writing to respond to Rep. Cera’s request for information on state distribution of severance tax proceeds to localities. The attached table broadly summarizes severance tax rates and whether proceeds are shared with local government in the 33 states with oil and gas production included in the data tables of the Energy Information Administration.

According to the National Council of State Legislatures, “Many states dedicate severance tax revenues to specific purposes, the most common being:

- Counties and other local governments (Colorado, Florida, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Tennessee, West Virginia, Wyoming);

- Conservation, reclamation and remediation (California, Colorado, Florida, Louisiana, Montana, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, West Virginia, Wyoming);

- Schools (Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Utah);

- Miscellaneous other purposes, such as Medicaid state matching funds (West Virginia); water development projects (Colorado, North Dakota and Wyoming), and administration of oil and gas wells (Indiana). Alaska's Constitution does not allow dedicated funds except for the Permanent Fund.

Ten oil- and gas-producing states – just under a third - do not have specific distributions to local government that we could identify. Other states share severance tax revenues with localities through formula (in several cases, the highway distribution formula is used), through apportioning funds on a standard basis between the county of production and the state, through direct return of funds or, as in the case of Virginia and Pennsylvania, through local severance tax authority.

Please let me know if I can provide any additional information. Thanks for your attention.

Sincerely, Wendy PattonSenior Project Director Download response with table[1] E-mail from Dan Bucks, former Director of Revenue for the state of Montana, dated 1/8/2014.

[2] West Virginia Budget and Policy Center, “Marshall University Natural Gas Study Proves Virtually Nothing,” Fiscal Policy Memo. 10/19/2011.

[3] Between June 2005, when income-tax reductions where approved, and November 2013, Ohio lost 4.1 percent of its nonfarm jobs, according to seasonally adjusted data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics survey of employers. That trailed only Michigan and Rhode Island; the U.S. average over that time period was a gain of 2.3 percent. See www.bls.gov.

[4] [4] Julia Haggerty, “How to get through the gas boom,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 6, 2011.

Tags

2014Revenue & BudgetTax ExpendituresTax PolicyWendy PattonPhoto Gallery

1 of 22