Income-Tax Repeal: A Bad Deal for Ohio

April 28, 2014

Income-Tax Repeal: A Bad Deal for Ohio

April 28, 2014

Download summary (2 pp)Download full report (6 pp)Miata graphicPress releaseRepealing the Ohio income tax would blow an enormous hole in the state budget. It would have to be paid for with gigantic budget cuts or major increases in other taxes.

Swap for sales tax would sting most taxpayers

Gov. John Kasich has made clear his interest in repealing Ohio’s income tax.[1] But what would income-tax repeal look like to Ohio families? This brief begins to examine that issue.

Gov. John Kasich has made clear his interest in repealing Ohio’s income tax.[1] But what would income-tax repeal look like to Ohio families? This brief begins to examine that issue.

Outright repeal of the income tax, the second-largest source of funding for the state budget, would sap it of more than $8 billion in annual revenue. That amounts to nearly as much as the state has budgeted to support K-12 education this fiscal year, or to put it a different way, twice the state’s total spending on higher education and corrections put together.

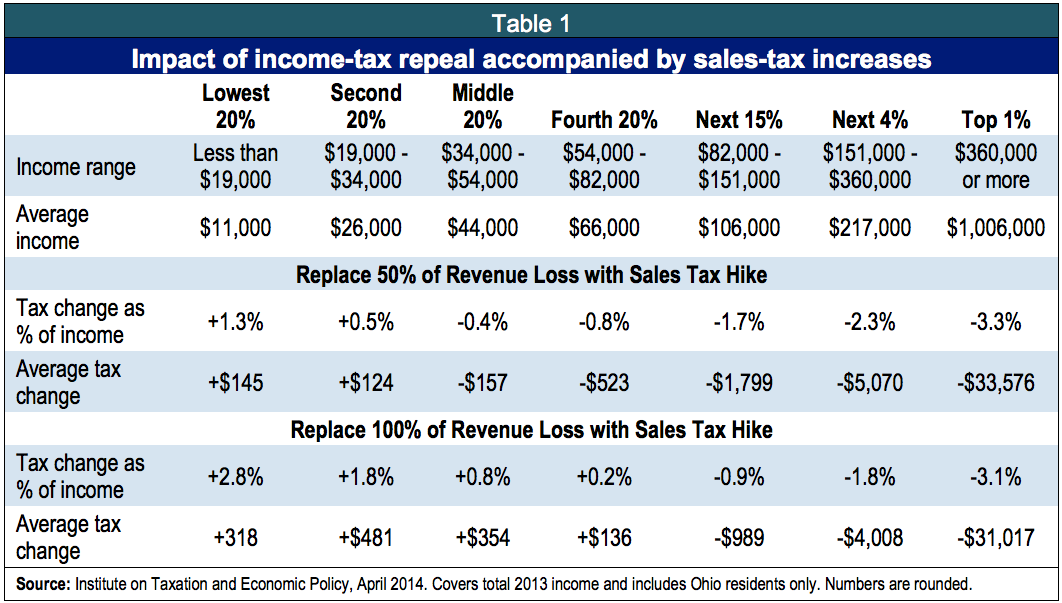

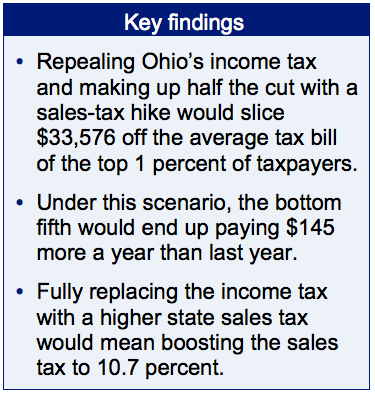

Eliminating the income tax, in short, would blow an enormous hole in Ohio’s budget, one that would have to be paid for with gigantic budget cuts or major increases in other taxes. Paying for even just half of it with a sales-tax increase – which is how the General Assembly paid for a significant share of last year’s income-tax cuts – would mean higher overall taxes for low- and moderate-income Ohioans according to a new analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. ITEP, a nonprofit research group based in Washington, D.C., with a sophisticated model of the state and local tax system, found that fully replacing the income tax with a higher sales tax would mean that the lowest-earning 80 percent of Ohioans would, as a group, see a tax hike. It would also mean boosting the state sales tax by nearly 5 percentage points, to 10.7 percent.

If just half of an income-tax repeal was swapped for a higher sales tax, ITEP found, the poorest fifth of Ohio taxpayers, who made less than $19,000 last year, would pay an additional $145 a year. By contrast, the top 1 percent, who made at least $360,000, would receive an annual tax cut of $33,576, or enough to purchase a top-end 2014 Mazda MX-5 Miata Grand Touring Convertible every year.[2] As a group, the bottom 40 percent of Ohioans would pay more in taxes than they did last year.

If half of the revenue loss from income-tax repeal were made up with sales tax hikes, ITEP calculated, the state sales tax would have to be increased by nearly 2.5 percentage points, pushing the state-only sales tax to 8.2 percent. All of Ohio’s counties and eight transit agencies collect local piggyback sales tax. Adding in these local sales taxes, the overall sales tax rate would be above 9 percent in 84 of Ohio’s 88 counties (the only exceptions being Butler, Lorain, Stark and Wayne counties, where the local sales tax rate is 0.75 percent and the combined rate would be a fraction below 9 percent).

If half of the revenue loss from income-tax repeal were made up with sales tax hikes, ITEP calculated, the state sales tax would have to be increased by nearly 2.5 percentage points, pushing the state-only sales tax to 8.2 percent. All of Ohio’s counties and eight transit agencies collect local piggyback sales tax. Adding in these local sales taxes, the overall sales tax rate would be above 9 percent in 84 of Ohio’s 88 counties (the only exceptions being Butler, Lorain, Stark and Wayne counties, where the local sales tax rate is 0.75 percent and the combined rate would be a fraction below 9 percent).

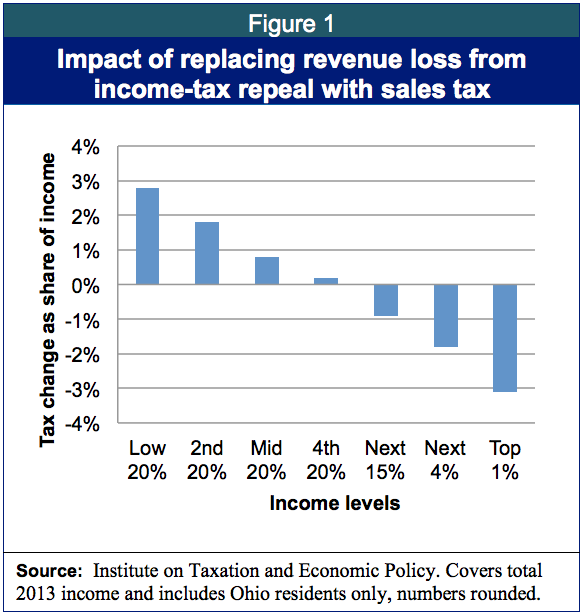

If all of the income tax cut were ultimately paid for by increases in the state sales tax, middle-income taxpayers on average would see a tax increase of $354 a year; for the poorest fifth of taxpayers, it would be $318. Yet the top 1 percent would see, on average, an annual tax cut worth more than $31,000. Figure 1 shows how income-tax repeal, funded entirely by an increase in the state sales tax, would affect Ohio taxpayers in different income groups.

Table 1 provides a more detailed breakdown of the impact of income-tax repeal if half of it were funded by a sales-tax increase, or if it all of it were, respectively. Of course, if only half of it were paid for, that would mean billions of dollars a year would not be available for public services.

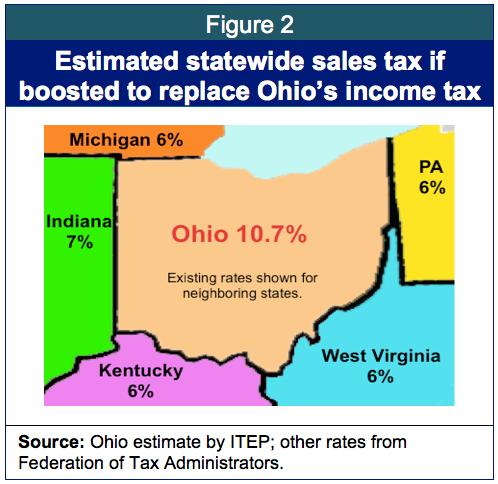

The state sales tax would need to rise by nearly 5 percentage points, to 10.7 percent, to finance repeal of the income tax paid by Ohio residents. As Figure 2 shows, this would leave Ohio with a state sales tax far higher than any neighboring state – in fact, Ohio’s state sales tax would be the highest in the country.[3]

The state sales tax would need to rise by nearly 5 percentage points, to 10.7 percent, to finance repeal of the income tax paid by Ohio residents. As Figure 2 shows, this would leave Ohio with a state sales tax far higher than any neighboring state – in fact, Ohio’s state sales tax would be the highest in the country.[3]

However, that does not include local sales taxes. As noted earlier, every county in Ohio collects sales tax, as do some local transit agencies. Based on tax collections, the local sales-tax rate across Ohio averaged 1.28 percent in fiscal year 2013.[4] Adding this to the new state rate, the average sales tax rate across the state would be about 12 percent if the sales tax were increased to pay for all of income-tax repeal.

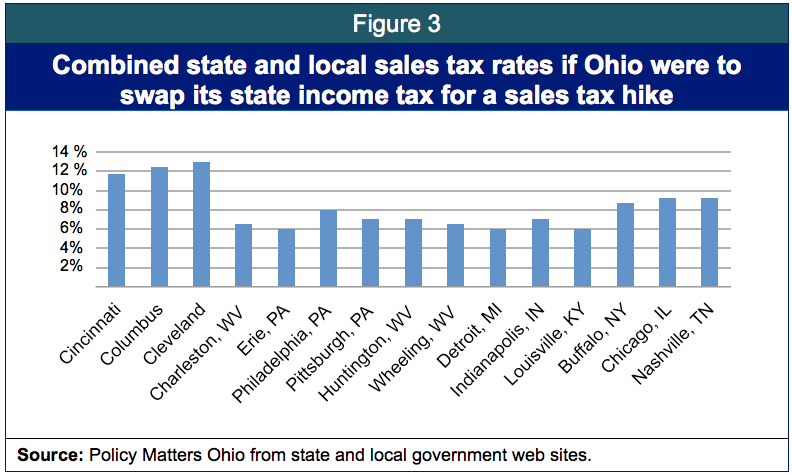

Indiana, Kentucky and Michigan do not have local general sales taxes. Among Ohio’s neighboring states, only seven municipalities in West Virginia[5] and Allegheny County (Pittsburgh) and Philadelphia in Pennsylvania[6] collect local general sales taxes.[7] Thus, most residents in surrounding states pay just the state rate. The highest general sales tax in any neighboring state is the 8 percent tax collected in Philadelphia. Chicago and Nashville each collect 9.25 percent sales taxes. But as Figure 3 shows, if Ohio repealed its income tax and replaced the revenue with sales tax, overall sales-tax rates in Ohio’s biggest cities would be much higher than in their counterparts in the area.

In his previous income-tax cut proposals, Gov. Kasich has sought to pay for a significant share of the tax cuts with increases in other taxes. Last year, the 10 percent cut in rates over three years approved by the General Assembly was accompanied by a quarter-penny increase in the sales tax. Tax Commissioner Joe Testa has testified that one of the guiding principles the administration uses in crafting tax reform policy is that “The tax system should be consumption-based instead of reliant on over-burdensome income taxes.”[8] Thus, additional income-tax cuts could well feature sales-tax increases.

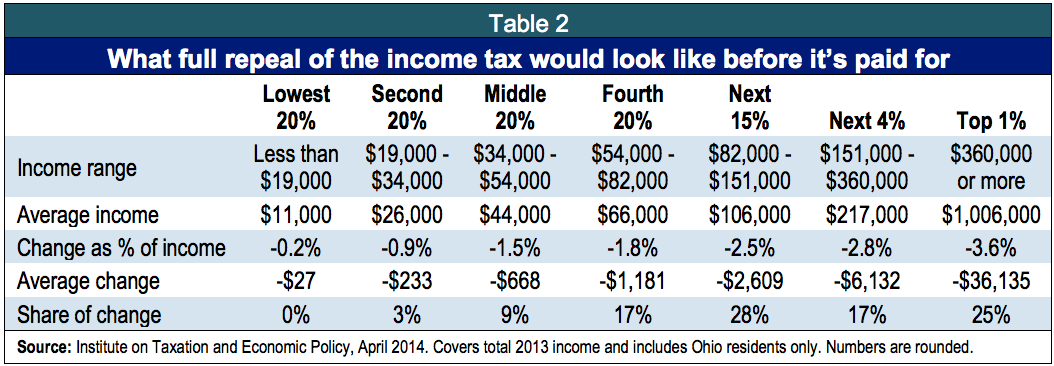

As noted above, income-tax repeal without major increases in other taxes or giant budget cuts is utterly implausible. The income tax is expected to account for 39.9 percent of Ohio state tax revenue in the current two-year budget.[9] Nonetheless, as part of its analysis, ITEP reviewed what repeal of the income tax alone would mean for Ohio taxpayers in different income groups, prior to the inevitable steps that would have to be taken to pay for it. ITEP found that the top 1 percent of Ohio taxpayers, who made at least $360,000 last year, on average would see an annual tax cut of $36,135. Middle-income taxpayers, who made between $34,000 and $54,000, would see a reduction of $668. Those in the bottom fifth of Ohio taxpayers, who made less than $19,000 last year, would see just a $27 annual tax cut.

Even under this scenario prior to the actions needed to pay for it, the top 1 percent on average would receive 54 times as much as middle-income taxpayers would get. Overall, a quarter of the tax cut would go to the top 1 percent, and 70 percent would go to the top 20 percent. The bottom three-fifths of Ohio taxpayers would get just 12 percent of the total tax reduction. ITEP’s calculations here and elsewhere in this report are based on 2013 income levels and tax rates, so they reflect what Ohio taxpayers would have paid in the tax season that just ended had the income tax been repealed.[10] Table 2 shows how repeal of Ohio’s income tax prior to steps taken to pay for it would affect taxpayers in different income groups.

The federal offset

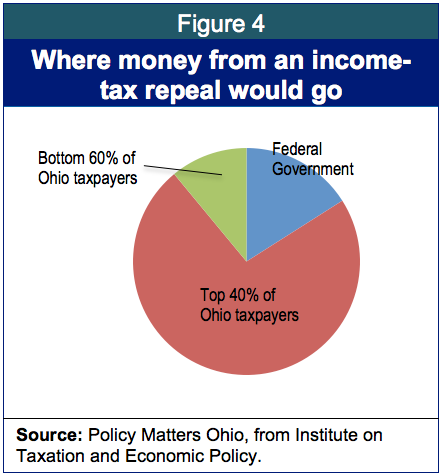

By any measure, income-tax repeal would primarily benefit the most affluent Ohioans while reducing the state’s ability to deliver services that Ohio’s communities and economy need. It would also siphon money out of Ohio, since it would reduce the amount that Ohio taxpayers could deduct on their federal tax returns. ITEP estimates that this “federal offset” would add up to more than $1 billion a year, or nearly one dollar in every six of the tax cut. As shown in Figure 4, this is considerably more than the entire tax cut that would be received by the lowest-earning 60 percent of Ohio taxpayers.

By any measure, income-tax repeal would primarily benefit the most affluent Ohioans while reducing the state’s ability to deliver services that Ohio’s communities and economy need. It would also siphon money out of Ohio, since it would reduce the amount that Ohio taxpayers could deduct on their federal tax returns. ITEP estimates that this “federal offset” would add up to more than $1 billion a year, or nearly one dollar in every six of the tax cut. As shown in Figure 4, this is considerably more than the entire tax cut that would be received by the lowest-earning 60 percent of Ohio taxpayers.

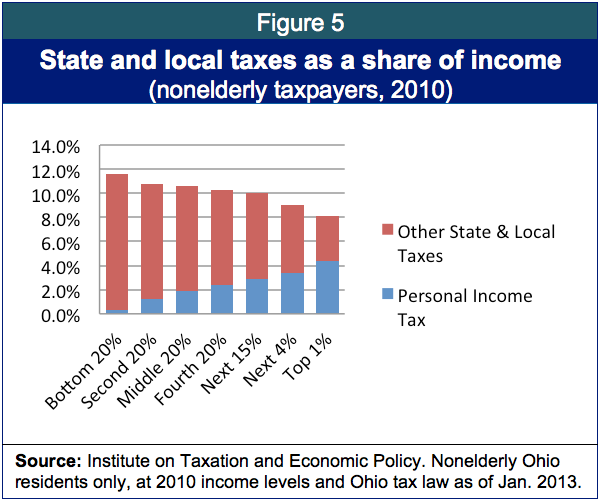

Ohio’s tax system already is weighted in favor of upper-income taxpayers, who pay a much smaller share of their income in state and local taxes that lower-income taxpayers do. A 2013 ITEP analysis, which examined how much nonelderly taxpayers pay based on income levels in 2010, found that the lowest-earning fifth of Ohio taxpayers paid only 0.3 percent of their income in state income tax, just a fraction of total state and local taxes that added up to 11.6 of their incomes.[11] Figure 5 based on this earlier analysis shows the total shares of income paid by each income group in income tax and total state and local taxes, respectively.

Figure 5 demonstrates that repealing the income tax would have little impact on the overall taxes paid by the poorest Ohioans. It would take an already unbalanced tax system and tilt it further in favor of the most affluent. Moreover, as shown earlier, most of the tax cuts that middle-income Ohioans would see from income-tax repeal would be wiped out if the sales tax were used to replace just half of the lost revenue from such a repeal. And that would still require billions of dollars in annual cuts to public services.

Figure 5 demonstrates that repealing the income tax would have little impact on the overall taxes paid by the poorest Ohioans. It would take an already unbalanced tax system and tilt it further in favor of the most affluent. Moreover, as shown earlier, most of the tax cuts that middle-income Ohioans would see from income-tax repeal would be wiped out if the sales tax were used to replace just half of the lost revenue from such a repeal. And that would still require billions of dollars in annual cuts to public services.

Conclusion

The income tax is the only state tax that is based on ability to pay. Slashing it without making up most of the revenue is a prescription for financial disaster, or huge cuts in public services. Yet making up the revenue with other taxes would shift who pays taxes from the affluent to everybody else. It’s no coincidence that five of the six states with the most regressive tax systems lack a general personal income tax.[12] Wiping out the income tax would be a bad deal for Ohio.

[1] Higgs, Robert, “Kasich says he hopes to get income tax rates below 4 percent, won't curtail Ohio's death penalty,” The Plain Dealer, Feb. 13, 2014, at http://bit.ly/1fbseTx. “Part of Kasich’s platform when he ran for governor was to eliminate the state income tax. “That’s always been my goal,” he said again Thursday. While that has not come to pass, Kasich said it has always remained his goal.”

[2] See http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/car-prices/ohio/mazda-mx-5-miata-grand-touring-4-cyl-mt.htm.

[3] See Federation of Tax Administrators, State Sales Tax Rates And Food & Drug Exemptions, As of Jan. 1, 2014, www.taxadmin.org/fta/rate/sales.pdf.

[4] That local sales-tax rate is based on the $2 billion collected in local sales tax in Ohio in Fiscal 2013, compared to the $8.6 billion in state sales tax. See Ohio Department of Taxation, 2013 Brief Summary of Ohio’s Taxes, pp. 63 and 106, at www.tax.ohio.gov/communications/publications/brief_summaries/2013_brief_summary.aspx.

[5] West Virginia State Tax Department, Local Sales and Use Tax, at http://bit.ly/1fbEIue.

[6] Pennsylvania Department of Revenue, Consumption Tax Rates, at http://bit.ly/1pzoM9i.

[7] Counties and municipalities in Indiana may collect food and beverage taxes on restaurant sales and certain other prepared food. The tax is 1 percent in some counties and municipalities and is a maximum 2 percent, as it is in Marion County (Indianapolis). See http://www.in.gov/dor/reference/files/cd30.pdf.

[8] Testa, Joe, Testimony to the Ohio House of Representatives Tax Reform Legislative Study Committee, Aug. 21, 2013, p. 2.

[9] Ohio Office of Budget and Management, Actual and Estimated Revenues for the General Revenue Fund, Fiscal Years 2012 to 2015, email from OBM, Oct. 28, 2013.

[10] Thus, additional reductions in income-tax rates approved last year that take effect after 2013 are not included in this analysis.

[11] The earlier ITEP report is not directly comparable to the figures in this report on income-tax repeal and sales-tax replacement, as it covered an earlier time period and included nonelderly taxpayers vs. all taxpayers.

[12] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax System in All Fifty States, 4th Edition, p. 4, at http://www.itep.org/pdf/whopaysreport.pdf. ITEP used an average of three different measures comparing how much of their income taxpayers in different income groups paid in state and local taxes. See p. 130 for a description.

Tags

2014Ohio Income TaxRevenue & BudgetTax ExpendituresTax PolicyZach SchillerPhoto Gallery

1 of 22