Severance tax review (HB 375, HB 212 and the Kasich fracking proposal)

January 14, 2014

Severance tax review (HB 375, HB 212 and the Kasich fracking proposal)

January 14, 2014

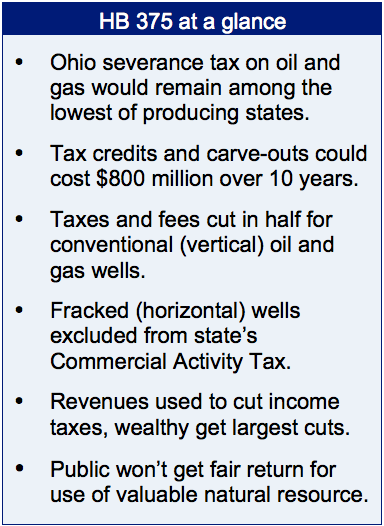

Download summary (2 pp)Download full report (13 pp)Press releaseThe proposed severance tax in House Bill 375 would shortchange Ohioans by undervaluing the state’s natural resources and granting up to $800 million over ten years in breaks and exclusions.

Executive summary

House Bill 375 proposes the lowest rates and most generous provisions for the oil and gas industry of three severance tax proposals considered in Ohio during the past year. This analysis compares current Ohio law with HB 375, introduced on Dec. 4, 2013 and sponsored by Matt Huffman, R-Lima, and two others: the Kasich administration proposal included in (and removed from) HB 59, the budget bill for fiscal years 2014-15; and HB 212, introduced by Rep. Bob Hagan, D- Youngstown.

House Bill 375 proposes the lowest rates and most generous provisions for the oil and gas industry of three severance tax proposals considered in Ohio during the past year. This analysis compares current Ohio law with HB 375, introduced on Dec. 4, 2013 and sponsored by Matt Huffman, R-Lima, and two others: the Kasich administration proposal included in (and removed from) HB 59, the budget bill for fiscal years 2014-15; and HB 212, introduced by Rep. Bob Hagan, D- Youngstown.

Our comparison reveals important differences:

- HB 212 proposes severance tax rates and uses of severance tax revenues similar to those of major producing states.

- The Kasich proposal included a rate similar to the region on oil and natural gas liquids, but lower than for dry gas. It proposed using most of the revenue for income-tax cuts, which would have benefited wealthy households more than middle- and lower-income households.[1]

- HB 375 proposes the lowest severance tax rates of the three proposals. The sponsor anticipates tax credits and carve-outs will cost $800 million over 10 years.[2] Most of the revenue will be used for income-tax cuts, benefitting the wealthiest Ohioans.

Ohio legislators are responsible for negotiating fair payment for the extraction of natural resources and using the proceeds to build lasting value for the people of the state. HB 375 would improve the severance tax on oil and gas in Ohio, but provisions of the bill need to be strengthened or changed. In its current form, it undersells a valuable resource. Recommendations to improve the bill include:

- Raise the tax rates. HB 375’s severance tax rates are lower than most oil- and gas-producing states, particularly states with active drilling in shale. They need to be higher, in line with other fracking states.

- Provide ODNR with funding necessary for mandated work. HB 375 reduces the Department of Natural Resource’s share of severance tax proceeds by reducing rates on some production and repealing the regulatory cost recovery assessment. The bill would reduce revenue supporting oversight, reclamation and mapping even as the industry expands rapidly. The eventual cost of oversight of a fracking boom may be higher than anticipated today.

- Trim and target tax breaks. HB 375 subsidizes the oil and gas industry through tax credits and exclusions, yet requires nothing in return. With its new severance tax, Illinois uses subsidy to benefit working families. Subsidies should seldom be given, but when they are, they should incentivize specific behavior, like hiring Ohio workers rather than out-of-state work crews.

- Eliminate or narrow the cost recovery period. Horizontal drilling and well stimulation are high-cost, high-yield techniques that are standard for extraction of shale resources. The tax code should evolve as technology does. Ohio does not need to adopt tax favors fought for by the oil and gas industry in other states and earlier decades.

- Eliminate the exclusion from the CAT. The exclusion from the state’s Commercial Activity Tax for horizontal-well production that would be taxed under HB 375 is a special-interest carve-out. Carve-outs have been opposed by many stakeholders to prevent exclusions and breaks from eroding the CAT’s efficiency and forcing rates to rise.

- Eliminate or narrow the income tax credit. This tax credit goes far beyond helping landowners with bad lease terms and could be very costly. Auditing could be difficult: ownership interests may be finely parsed, widely dispersed, with widespread assignment of tax benefit.

- Base the severance tax on gross value instead of net proceeds. The language in HB 375 that defines "net proceeds" as allowing the exclusion of "any" post-production costs invites excessive deductions in a way that "gross value" does not.

- Use severance tax proceeds to meet the needs of Ohioans. HB 375’s proposed use of severance tax revenue for income-tax cuts results in a distribution that favors the wealthy. Policy Matters found that Gov. Kasich’s 2012 proposal to increase the severance tax and use the revenues for an income-tax cut resulted in a $42 average tax cut for Ohio households in the middle quintile of earners and a $2,300 tax cut for the wealthiest households in years that the income tax giveback fund is $500 million. While HB 375 would require its own analysis – the numbers would be smaller – the basic pattern would be the same.

Severance taxes are needed to ensure proper oversight and regulation of the fracking industry, to mitigate impacts, to meet current needs of the state, and to build diversity in the economy for after the boom is over. An adequate, responsible severance tax can help do all those things. We must not lose the opportunity to harness the boom and invest in the future for all Ohioans.

Introduction

House Bill 375 proposes the lowest rates and most generous provisions for the industry of three severance tax proposals considered in Ohio during the past year. This analysis compares current Ohio law with HB 375, introduced on Dec. 4, 2013 and sponsored by Matt Huffman, R-Lima, and two others: the Kasich administration proposal included in (and removed from) HB 59, the budget bill for fiscal years 2014-15, and HB 212, introduced by Rep. Bob Hagan, D- Youngstown.

House Bill 375 proposes the lowest rates and most generous provisions for the industry of three severance tax proposals considered in Ohio during the past year. This analysis compares current Ohio law with HB 375, introduced on Dec. 4, 2013 and sponsored by Matt Huffman, R-Lima, and two others: the Kasich administration proposal included in (and removed from) HB 59, the budget bill for fiscal years 2014-15, and HB 212, introduced by Rep. Bob Hagan, D- Youngstown.

Ohio legislators are responsible for negotiating fair payment for the extraction of Ohio’s natural resources and using the proceeds to build lasting value for the people of the state.

Our comparison reveals important differences:

- HB 212 proposes severance tax rates and uses of severance tax revenues similar to those of major producing states.

- The Kasich proposal included a rate similar to the region on oil and natural gas liquids, but lower than for dry gas. It proposed using most of the revenue for income tax cuts, which would have benefited wealthy families more than middle- and lower-income families.[1]

- HB 375 proposes the lowest severance tax rates of the three proposals. The sponsor anticipates tax credits and carve-outs will cost $800 million over 10 years.[2] Most of the revenue will be used for income tax cuts, benefitting the wealthiest.

HB 375 proposes to improve the severance tax on oil and gas in Ohio, a laudable goal. But provisions of the bill need to be strengthened or changed. In its current form, it undersells a valuable resource.

What is a severance tax?

The severance tax is paid by private interests that profit from natural resources like coal, oil, natural gas, precious metals, uranium, limestone, even sand. Companies that mine or drill for natural resources are called ‘producers’ but they do not produce natural resources, they extract (“sever”) resources from the land. Once removed, natural resources cannot be replenished. For this reason, proceeds of a severance tax are typically invested in mitigating the impacts of drilling on communities, for something that brings lasting value to people: education, for example, or to diversify the economy for after the boom. In addition, an adequate share of severance tax collections need to be dedicated to regulation and environmental remediation of current or past mining and drilling.

Ohio’s severance tax

Under Ohio law, the severance tax is described as follows: “For the purpose of providing revenue to administer the state’s coal mining and reclamation regulatory program, to meet the environmental and resource management needs of this state, and to reclaim land affected by mining, an excise tax is hereby levied on the privilege of engaging in the severance of natural resources from the soil or water of this state.” (Ohio Revised Code 5749.02).

Ohio was a major producer of oil in the 1800s and natural gas production led to Toledo’s rise as a center for glass production, but production of both oil and gas has been modest in Ohio for a long time. Ohio’s severance tax on oil and natural gas dates back to the 1970s, and is still based on volume, not value as in the majority of producing states. The rates are low.[3] Production is not large; proceeds of the severance tax are small and used to support industry oversight and geological mapping. Although an assessment was imposed for regulatory and environmental purposes in 2010, Ohio’s severance taxes and fees on oil and gas remain among the lowest of all producing states.[4]

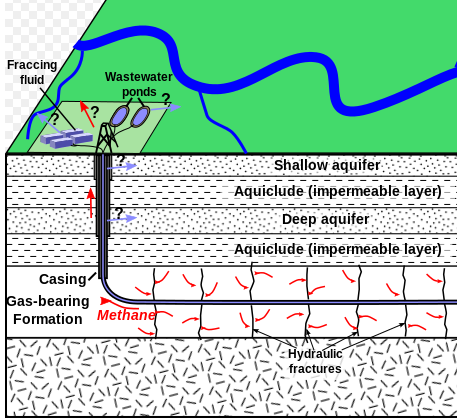

The industry is growing in Ohio as a result of relatively new techniques of horizontal drilling, known as fracking, and well stimulation in shale rock deep under the surface. Oil and gas companies have leased mineral rights and drilled exploratory wells, with promising results.[5] Families, communities and school districts have received checks for leases and are hoping for royalties. Economic activity has increased in some counties and hopes are high in these places for a natural resource boom.[6]

As production increases, public costs rise in terms of wear and tear on roads, bridges, water treatment facilities, emergency and safety services, housing, social services and other public infrastructure.[7] As a new oil and gas industry emerges, Ohio’s elected officials must ensure the tax on oil and gas is set at a level to adequately cover public costs, as well as to compensate the people of the state for the permanent removal of valuable natural resources.

House Bill 375

Through its major components, HB 375 would:

- Levy a severance tax on well owners of oil and gas severed from horizontal wells. The bill retains Ohio’s current, volume-based severance tax for production from vertical wells, but replaces it for horizontal wells or fracking. Production from horizontal wells would be covered by a new severance tax based on value of net proceeds at a proposed rate of 1 percent for five years, then 2 percent until production becomes marginal (less than 17 barrels or 10,000 metric cubic feet per day).

- Create a non-refundable income tax credit for the amount of horizontal-well severance tax paid. Anyone who pays severance taxes and personal income taxes (an individual or pass through entity) could offset Ohio personal income taxes with severance tax paid – or, they could assign the income tax credit to another ‘designated taxpayer’ with an interest in the well under specified guidelines. The tax credit can be carried forward for seven years.

- Repeal the regulatory cost recovery assessment on oil and gas well owners. Ohio’s oil and gas regulatory cost recovery assessment, similar to conservation assessments used in many states, was imposed as the industry grew in 2010. The increase on a barrel of oil was a dime; it was a half-cent on dry natural gas. HB 375 would repeal this fee. This cuts in half the severance tax and payments on conventional (vertical) well production.

- Reduce the severance-tax rate on natural gas extracted from non-horizontal wells. The bill would reduce the volume-based rate on natural gas produced from vertical wells to 1.5 cents per thousand cubic feet (mcf) from 2.5 cents per thousand cubic feet (mcf). Together, the rate reduction and the repeal of the regulatory cost recovery assessment cut in half the severance tax and fee payments on natural gas production from conventional (vertical) wells.

- Exclude from the tax base of the commercial activity tax (CAT) receipts from the sale of oil or natural gas severed through use of a horizontal well. The CAT would still cover oil and gas produced through vertical wells.

The proceeds of the horizontal well severance tax would be put into the “Horizontal Well Fund” and distributed as follows:

- Funding for industry oversight, administration of reclamation of orphaned wells and geological mapping activities within the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) will continue, funded from revenues on vertical wells and a share of proceeds from the new horizontal well tax, which would be based on collections as if current severance tax rates (net of the regulatory cost recovery fee) were in place for the horizontal wells.

- If collections for activities in ODNR exceed budgeted appropriations, half of the excess would be used for remediation of abandoned wells and immediate health and safety concerns, as outlined under existing law in Ohio Revised Code 1509.071.

- All other funds in the Horizontal Well Fund would be allocated to the Income Tax Reduction Fund (ITRF) and used to reduce income taxes.

Table 1 compares the rates of existing severance tax proposals with current law and each other.

HB 375 keeps Ohio’s rates among the lowest in the nation. Severance tax rates and fees on production through vertical wells would be cut in half. Tiered rates of one and two percent, tied to time on the front end and production levels on the back end, are employed in the severance tax on horizontal wells. The base for taxation on horizontal wells becomes value based on net proceeds, which means “gross receipts from the severance of oil and natural gas less any post-production costs related to the sale of the oil or natural gas,” which include certain “costs related to gathering, processing, transporting, fractionating, and delivery for sale of oil or natural gas, and any adjustment for shrinkage.” (Exclusions – non-allowable costs - are not listed). Exclusion from the CAT tax and the income tax credit provide individual investors and pass through entities a lucrative deal.

The Kasich proposal

The Kasich administration’s severance tax proposal, introduced as part of HB 59, the Executive Budget for fiscal years 2014-15, would have established a tax on oil and natural gas liquids produced through horizontal wells at 4 percent, a rate similar to that in other producing states in the region. An initial rate of 1.5 percent was applied in the first year. The severance tax rate on dry natural gas produced through horizontal wells would have been lower than other producing states in the region and lower than HB 375’s 2 percent rate that kicks in after five years. The Kasich proposal was removed from HB 59 during the budget process.

The level of payment on production of natural gas and oil through vertical wells would have remained the same as in current law, but capped at 1 percent of value. Marginal production of vertical wells is exempted.

House Bill 212

HB 212 would increase severance taxes and fees on vertical wells slightly, and retain the regulatory cost recovery assessment and caps severance tax on dry gas at 1 percent of value. It would keep production of oil and gas of horizontal wells at 7.5 percent of value and retain the regulatory cost recovery assessment.

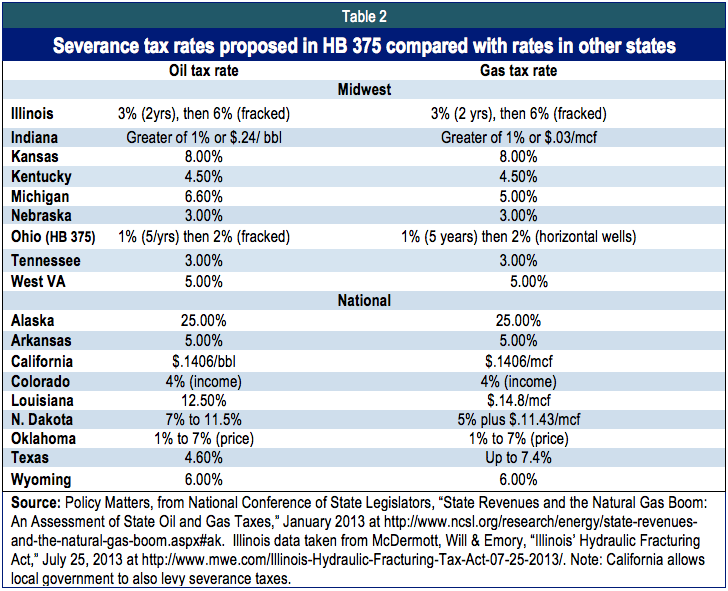

Table 2 shows that under House Bill 375, Ohio’s severance tax rates on oil and gas would remain among the lowest of the major producing states and regional states.

Tax credits and exclusions

HB 375 offers a personal income tax credit to payers of Ohio’s severance tax and excludes the horizontal well severance tax from the Commercial Activity Tax. The bill does not make up for revenue lost due to these features. According to sponsor Matt Huffman, HB 375 would yield $2.5 billion over 10 years through the severance tax, but the state would net $1.7 billion, due to the commercial activity tax exemption and the income tax credits.[8] The Ohio Oil and Gas Association projects that the tax will raise $2.69 billion over 10 years, and that the state will collect $2.07 billion.[9] According to these estimates, these tax breaks would cost the state between $620 million and $800 million over 10 years. If forecast production in all years were equal, the cost of HB 375 to the state would average $62 million to $80 million a year for the next decade. This subsidy of the oil and gas industry represents a significant expenditure. Since funds other than those used for industry oversight, reclamation and mapping are to be used for income tax reductions, monies collected from the severance tax will not recompense the state for the cost of the tax credit and exclusion.

Production is not equal in all years, and cost of these subsidies would be much lower in initial years, and rise with industry growth. The Legislative Service Commission fiscal note focuses on cost during the current biennium, finding that both local revenues and the state’s General Revenue Fund would be impacted. The GRF would not be affected in 2014 but would lose $8.5 million in 2015, a loss that would grow over time. Local losses would stem from impact on the Local Government Fund (which was cut in half in the last biennial budget) and on the Public Library Fund, each of which receive 1.66 percent of GRF tax collections. The loss to local governments is estimated to be in the tens of thousands of dollars in fiscal year 2014 and $300,000 in 2015, and would grow over time.[10]

Individual income tax credit. Under HB 375, any Ohio severance tax paid could be taken as a credit against the state’s individual income tax. Although the tax credit is not refundable, it may be carried forward for up to seven years. The tax credit may be assigned to someone else as long as the ‘designated taxpayer’ has an ownership interest in the well on which the severance tax is paid. This income tax credit could be used by both individuals and pass-through entities.

Some landowners in Ohio have been surprised to find that leases with oil and gas companies include severance tax liability as well as royalties. The income tax credit may help this group, but it is not targeted to them. With this income tax credit, the state boosts returns for all investors with interests in horizontal wells in Ohio. Auditing could be difficult: ownership interests may be finely parsed, widely dispersed, with widespread assignment of tax benefit.

Commercial Activity Tax exclusion. HB 375 would exempt payers of the new severance tax on horizontal wells from the Commercial Activity Tax. The CAT is the state’s general tax on business, and replaced the state’s corporate franchise tax in 2005. Ohio did not exclude the oil and gas industry from the general business tax during the 40 years that the severance tax has been in place. Today the CAT covers oil and gas production if the product is destined for a buyer in Ohio for use in Ohio. As with all products, oil and gas that’s produced in Ohio, even if transported through the state, is not subject to the CAT if it goes to another state.

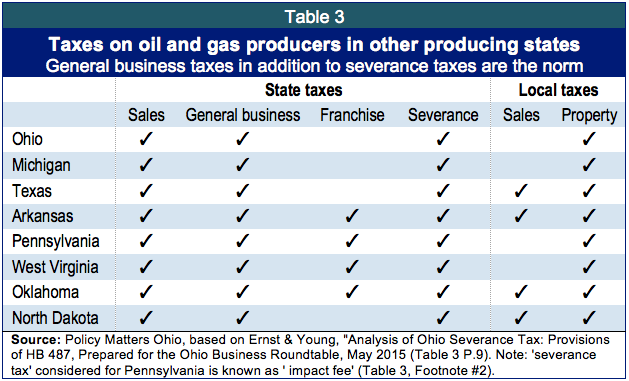

Other producing states levy general business taxes on oil and gas producers. A 2012 Ernst & Young analysis of taxes on oil and gas production in eight producing states deemed similar to Ohio found a general business was levied in all. (See Table 3.)

During the committee hearing on sponsor testimony, Rep. Matt Huffman suggested the severance tax on horizontal drilling would be a separate business tax on the industry, like the taxes specific to the financial and insurance industries. There are several reasons to be skeptical of this argument.

- Not all oil and gas would be exempt from the CAT. Proceeds of oil produced from conventional wells would remain subject to the CAT, while product of horizontal wells would be exempted. This suggests that the proposed exemption is simply a very large exclusion from the state’s general business tax, not a ‘separate tax on a separate industry.’

- Current statute defines the severance tax as an excise tax. The severance tax has not been conceived of as a general business tax in Ohio. (See ORC 5749.02.)

- Payers of the severance tax were not excluded from the corporation franchise tax, and they were not excluded from the CAT when it was created.[11] The financial, insurance and utility industries are not subject to the CAT and pay a separate business tax that has been in place since the CAT was established. At the time of the CAT’s creation, specific exemptions or credits were written into the tax code. Payers of the severance tax were not among those exempted.

The proposed exclusion for fracking is a special-interest carve-out in the Commercial Activity Tax. Carve-outs have been opposed by many stakeholders to prevent the CAT from becoming so pocked with exclusions and breaks that rates must rise as the efficiency of the tax is eroded.

Cost recovery loopholes

Both the Kasich administration proposal and HB 375 offer low initial rates to allow owners of horizontal well production to recover the cost of investment. Sometimes referred to as a ‘cost recovery period,’ sometimes referred to as a ‘tax holiday,’ initial preferential rates were offered by some of the oil and gas producing states over the past 20 years, dating back to when hydraulic fracturing and other techniques of well stimulation and horizontal drilling were unusual and costly compared to other techniques. Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) are now commonly used to extract resources from shale rock. Tax codes should evolve as technology evolves. As a high-cost method becomes the standard, favorable tax treatment needs to be phased out.

Point of taxation

HB 375 proposes that oil and gas be taxed on net proceeds rather than volume (barrels or metric cubic feet) as under current law, or market value of production, as under HB 212 and the Kasich administration proposal. Most states use market value or gross value, but also allow a variety of deductions from severance taxes.

All deductions narrow the base. The severance tax base proposed in HB 375 could be very narrow, because the language defining deductions is very broad. “Net proceeds” means “gross receipts from the severance of oil and natural gas less any post-production costs related to the sale of the oil or natural gas,” which include certain “costs related to gathering, processing, transporting, fractionating, and delivery for sale of oil or natural gas, and any adjustment for shrinkage.”[12] “Less any post production costs” is very loose language, as is the clarification of what such language includes, but not what it excludes. This may prove difficult for both the industry and the state. Montana used to have a local oil and gas production tax based on net proceeds (but administered by the state). The oil and gas industry preferred the net proceeds tax as long as the Department of Revenue never audited the deductions. The department audited the deductions more thoroughly beginning in the 1980s. The oil and gas industry then discovered that there were too many complexities and ambiguities involved in determining what deductions were allowable and too much uncertainty associated with appeals – so the law migrated to "gross value" as a simpler starting point.[13]

Distribution

Under HB 375, severance tax collections from vertical wells would continue to be distributed as under current law, with 90 percent of funds from the severance tax and the regulatory cost recovery assessment distributed to ODNR for the Oil and Gas Well Fund (Fund 5180), which administers oil and gas regulatory programs and other operating costs of the “Division of Oil and Gas Resources Management,” and also supports the administrative costs of plugging oil and gas wells in Ohio, including "orphan" or abandoned wells. The remaining 10 percent would be used for the Geological Mapping Fund (Fund 5110).

Proceeds from the new horizontal-well severance tax would go to the Horizontal Well Fund and be distributed in September of each year. By September 15, the tax commissioner would calculate and certify the amount of severance tax that would have been collected during the preceding fiscal year as if current severance tax law – in place as of December 31, 2013 – was in place (net of the regulatory cost recovery assessment.) Ninety percent of that amount is transferred from the Horizontal Well Fund to the Oil and Gas Well Fund and ten percent to the Geological Mapping Fund – as under current law, as with the distribution of severance tax proceeds from vertical wells.

The date of the calculation and certification of funds – September – does not coincide with dates for budgetary appropriations. A provision is made in HB 375 in case the Tax Commissioner’s calculation and certification is higher than the appropriation level passed in the biennial budget: At least half of any excess funds over and above appropriation must be used to address remediation, reclamation and health and safety problems of orphaned or abandoned wells.

The Legislative Service Commission fiscal note does not provide estimates of what the excess may be in any given year. However, it finds that under HB 375, revenues for the Oil and Gas Well Fund and Geological Mapping Fund will be reduced by $3.2 million or more in 2015 and beyond. Ninety percent of the loss, or an estimated $2.4 million, will impact the Oil and Gas Well Fund, which is 18.75 percent of appropriations for fiscal year 2015. According to the fiscal note: “Loss amounts in future years will grow as increasing quantities of oil and gas are severed from Ohio wells.”[14]

All remaining revenues of the Horizontal Well Fund would be used to reduce state personal income tax through the Income Tax Reduction Fund, which already exists in statute and in association with the state Rainy Day Fund.

The Kasich proposal removed from HB 59 proposed using funds for reduction of the state personal income tax. A later plan was proposed to use 25 percent for counties impacted by drilling and 75 percent for personal income tax reduction.[15]

HB 212 distributes proceeds of the tax to meet needs in Ohio. Just over two-thirds goes to local government, with the largest share for communities impacted by drilling. About 13 percent supports a long-term investment fund. Twenty percent is for industry oversight and environmental remediation.

Most states use proceeds of the severance tax to create lasting value and boost economic opportunity for residents (see appendix). Typical use of earnings range from checks to residents (Alaska’s “Citizen Dividend” – which is not used to reduce another tax) to general fund purposes, education, infrastructure, economic diversification and economic development and research and development.

Ohio has many needs for the revenues that would be raised by an adequate severance tax. Adequate funding for regulation and oversight is paramount. Horizontal wells are large scale, and the industry continues to project rapid expansion.[16] Yet share of severance tax proceeds for ODNR oversight purposes decreases under the provisions of HB 375. In hearings, legislators have discussed a need for remediation of orphaned wells, but the HB 375 boost in funding for this purpose is through an uncertain source: half of excess revenues over ODNR’s forecast and appropriated share. This does not provide a stable basis for planning capital projects like reclamation.

Severance tax funds are needed to pay for costs to communities where production is taking place: cost of wear and tear on roads and bridges, water treatment, traffic controls, housing, planning, and long-term economic diversification.

The state has long-term unmet needs as well. College tuition in Ohio is too high and need-based financial aid is too low. K-12 schools have seen funding reduced by hundreds of millions. Local governments operate with a $1.5 billion less, on a biennial basis, than they had in fiscal years 2010–11. Ohio’s growing industries funded these essentials in the twentieth century and new potential growth industries should become funding sources in this century.

Only HB 212 outlines a program for uses that responds to needs as well as a long-term investment strategy for the state.

Impact of taxes on natural resource industries

Ohio has low state taxes on natural resource extraction. In May 2012, the Ohio Business Roundtable commissioned a study by Ernst and Young of the impact of state taxes on the natural gas industry in eight states. It concluded that taxes on natural gas production in Ohio – all taxes, not just the severance tax – were the 8th lowest among comparable producing states (this was both with and without the administration proposal to tax natural gas).[17]

A severance tax that covers costs of drilling on communities and compensates for the removal of valuable resources will not halt development, if this is where the resources lie. The oil and gas extraction industry will make choices about drilling based on productivity, potential, access, location, infrastructure, market access, and logistics. Taxes are not the key factor.[18]

Studies of state taxes have shown that severance tax rates have little effect on production. In 2010, West Virginia, with a severance tax rate of 5 percent on oil and gas, led the country in the number of new gas wells drilled. And, despite the lack of a severance tax, Pennsylvania drilled less than half (833) the number of new wells as West Virginia (1,896). In the late 1990s, Montana lowered production tax rates and added incentives for new production while Wyoming eliminated a severance tax reduction. As a result of the policy changes, the overall tax rate on the natural gas industry was 50 percent higher in Wyoming than in Montana. Both states subsequently underwent a boom in natural gas drilling, but Wyoming has fared far better. Between 2000 and 2006, Wyoming added over $10 billion in production value, while Montana only added $2 billion.[19]

Natural resource extraction depends on the nature of the resource underground and the industrial structure above ground. Ohio, with complex upstream and downstream suppliers, growing transmission capacity, a big market in-state and close proximity to industrial markets in the east and Midwest, offers unique advantages.[20] Return on investment will be driven by factors larger than state severance taxes, especially given that the severance tax is written off against federal taxes, and the impact is largely born by the customer - who is largely out of state.[21]

Conclusion and recommendations

Ohio needs to improve the state severance tax. House Bill 375 is meant to address this need, but many of the provisions of the bill need to be changed. The rates are too low. Tax credits and exclusions are not funded, making the proposal very costly to the state. The primary use of revenues – income tax cuts – ignores pressing needs of impacted communities and the state and disproportionately benefits the wealthy. We should improve the bill in these eight ways:

- Raise the tax rates. HB 375’s severance tax rates are lower than most oil- and gas-producing states, particularly states with active drilling in shale. They need to be higher, in line with other fracking states. If the severance tax rate is based on value, collections fall as prices or production falls with market trends, cushioning the industry from disproportionate burden.

- Provide ODNR with funding necessary for mandated work. HB 375 reduces ODNR’s share of severance tax proceeds by reducing rates on some production and repealing the regulatory cost recovery assessment. The bill would reduce revenue supporting oversight, reclamation and mapping even as the industry expands rapidly. The eventual cost of oversight of a fracking boom may be higher than anticipated today.

- Trim and target tax breaks. HB 375 subsidizes the oil and gas industry through tax credits and exclusions, yet requires nothing in return. With its new severance tax, Illinois uses subsidy to benefit working families. The tax rate of 6 percent on natural gas is reduced by 0.25 percent for the life of the well when a minimum of 50 percent of the total workforce hours on the well site are performed by Illinois construction workers being paid wages equal to or exceeding the general prevailing rate of hourly wages. Subsidies provided through Ohio’s tax code should seldom be given, but when they are, they should incentivize specific behavior, like hiring Ohio workers rather than out-of-state work crews.

- Eliminate or narrow the cost recovery period. Horizontal drilling and well stimulation are high-cost, high-yield techniques that are standard for extraction of resources such as those in Ohio’s shale formations. The industry won cost recovery tax holidays in other states in earlier years to help develop these new techniques, but the techniques are no longer experimental. As technology has evolved, the tax code should as well. Ohio does not need to adopt tax favors fought for by the oil and gas industry in other states and earlier decades. If it does, it should tie such breaks to garnering specific benefits for working families and communities where drilling is located.

- Eliminate the exclusion from the CAT. The exclusion from the state’s Commercial Activity Tax for horizontal-well production that would be taxed under HB 375 is a special-interest carve-out. Carve-outs have been opposed by many stakeholders to prevent exclusions and breaks from eroding the CAT’s efficiency and forcing rates to rise. The oil- and gas-production industry did not get special treatment under the corporation franchise tax, nor when the CAT originated. There is no reason for it to get such treatment now.

- Eliminate or narrow the income tax credit. This tax credit goes far beyond helping landowners with bad lease terms and could be very costly. Auditing could be difficult: ownership interests may be finely parsed, widely dispersed, with widespread assignment of tax benefit.

- Base the severance tax on gross value instead of net proceeds. The language in HB 375 that defines "net proceeds" as allowing the exclusion of "any" post-production costs invites excessive deductions in a way that "gross value" does not.

- Use proceeds of the severance tax to meet the needs of Ohioans. HB 375’s use of the severance tax revenue for income tax cuts results in a distribution that favors the wealthy. Policy Matters found that Gov. Kasich’s 2012 proposal to increase the severance tax and use the revenues for an income-tax cut resulted in a $42 average tax cut for Ohio households in the middle quintile of earners and a $2,300 tax cut for the wealthiest households in years that the income tax giveback fund is $500 million. While HB 375 would require its own analysis – the numbers would be smaller – the basic pattern would be the same.

Severance taxes are needed to ensure proper oversight and regulation of the industry, to mitigate impacts, to meet current needs of the state and to build diversity in the economy for after the boom is over. An adequate, responsible severance tax can help do all those things. We must not lose the opportunity to harness the boom for a brighter future for all Ohioans.

[1] Policy Matters Ohio: “Ohio needs a strong income tax,” at www.policymattersohio.org/strong-income-taxfeb2012.

[2] Gongwer Ohio, “Huffman pitches severance tax proposal: oil industry not united in support,” Volume #82, Report #238--Tuesday, December 10, 2013 at http://bit.ly/1dKgFLy.

[3] Policy Matters Ohio, “Beyond the Boom: Ensuring Adequate Payment for Mineral Wealth Extraction,” at www.policymattersohio.org/beyond-boom-dec2011.

[4] Society for Petroleum Evaluation Engineers, 2012, cited in Porter Wright Ohio Oil and Gas Report at http://www.oilandgaslawreport.com/2012/12/27/how-ohio-currently-stacks-up-on-taxes-on-oil-and-gas-operations/.

[5] See Ohio energy production rising as wells increase (Associated Press, 1/2/2014), also Ohio's 245 Utica shale wells producing at a rate of $1 billion a year (Akron Beacon Journal, 12/31/2013).

[6] Multistate Shale Research Collaborative, “Exaggerating the Employment Impact of Shale Drilling: How and Why,” November 2013 at www.multistateshale.org/shale-employment-report. State analysis finds that although the industry projected shale job creation of scores of thousands, even hundreds of thousands, about 2500 direct, core jobs associated with shale extraction have been created since 2011. However, some eastern Ohio counties have seen unemployment drop. See “State Reports Find Increases In Petroleum Production, Employment From Fracking” Gongwer Ohio, January 2, 2014 at: www.gongwer-oh.com/programming/news.cfm?article_ID=830010202 - sthash.XYhS0NpK.dpuf, also,

[7] Pennsylvania Budget and Policy Center, “Responsible Growth: Protecting the Public Interest with a Natural Gas Severance Tax,” https://pennbpc.org/sites/pennbpc.org/files/Severance%20Tax%20Paper%20Brief_0.pdf. Deborah Rogers, “Externalities of Shale: Health Impact Costs,” Energy Policy Forum at http://energypolicyforum.org/2013/04/03/shale-externalities-health-impact-costs/; Marcellus Shale Education and Training Center (MSETC), “Natural Gas Drilling Effects on Municipal Governments in the Marcellus Shale Region, (Part IV), Local Government Survey Results from Clinton and Lycoming Counties,” Cited in Policy Matters Ohio, “Beyond the Boom: Ensuring Adequate Payment for Mineral Wealth Extraction,” policymattersohio.org/beyond-boom-dec2011.

[8] Gongwer Ohio, “Huffman pitches severance tax proposal: oil industry not united in support,” Volume #82, Report #238--Tuesday, December 10, 2013 at http://bit.ly/1dKgFLy.

[9] Scott Ziance of Voreys, Sater, Seymour and Pease LLP, Proponent testimony on HB 375 on behalf of the Ohio Oil and Gas Association, January 8, 2014, at www.ohiohouse.gov/committee/ways-and-means.

[10] Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Fiscal note and local impact statement, House Bill 375 as introduced, January 8, 2015 at www.lsc.state.oh.us/fiscal/fiscalnotes/130ga/hb0375in.pdf.

[11] According to the Ohio Department of Taxation, the corporation franchise tax did not apply

to: Nonprofit corporations, Credit unions, “S” corporations and qualified subchapter S subsidiaries (“QSSS”), Limited liability companies (LLCs), if treated as a partnership for federal tax purposes, Real estate investment trusts (REITs), regulated investment companies (RICs) and real estate mortgage investment conduits (REMICs), Corporations in Chapter 7 bankruptcy proceedings, Corporations exempt under federal law. Qualifying holding companies were exempt from the net worth base. See Ohio Department of Taxation, “Brief Summary of Ohio’s Taxes,” at http://1.usa.gov/1ceHDtS.

[12] Bricker & Eckler, “New Severance tax Proposal Introduced in Ohio House of Representatives,” 12/5/2013 at www.bricker.com/publications-and-resources/publications-and-resources-details.aspx?publicationid=2768.

[13] E-mail from Dan Bucks, Montana’s former director of revenue, dated Jan. 8, 2014.

[14] Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Fiscal note and local impact statement, House Bill 375 as introduced, January 8, 2015 at www.lsc.state.oh.us/fiscal/fiscalnotes/130ga/hb0375in.pdf.

[15] Gongwer Ohio, “New Local Severance Tax Plan Remains Tough Sell To GOP Lawmakers,” volume 82, report 114, article #2, June 13, 2013.

[16] Dr. Benjamin H. Thomas, Thomas Consulting LLC “Interested Party Testimony on HB 375,” January 8, 2013, available at www.ohiohouse.gov/committee/ways-and-means.

[17] Ernst & Young, "Analysis of Ohio Severance Tax: Provisions of HB 487, Prepared for the Ohio Business Roundtable, May 2015 (Table 3 P.9).

[18] Julia Haggerty, “How to get through the gas boom,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 6, 2011.

[19] This section draws on the work of Sean O’Leary and Ted Boettner of the West Virginia Budget and Policy Center, Marshall University Natural Gas Study Proves Virtually Nothing, Fiscal Policy Memo. 10/19/2011.

[20] Ohio Business Development Coalition, “Marcellus and Utica shale gas supply chain, “ white paper, 2011.

[21] Since they are deductible from federal corporate income taxes, each dollar in state severance tax is offset by the effective federal rate of the producer (the nominal federal tax rate is 35 percent, so this is, in nominal terms, a $.35 cent deduction against federal taxes.) Policy Matters Ohio, “Beyond the Boom: Ensuring adequate payment for mineral wealth extraction,” December 2011 at www.policymattersohio.org/beyond-boom-dec2011.

Tags

2014EnergyEnvironmentFrackingRevenue & BudgetSeverance TaxTax PolicyWendy PattonPhoto Gallery

1 of 22