Home Insecurity 2014

May 09, 2014

Home Insecurity 2014

May 09, 2014

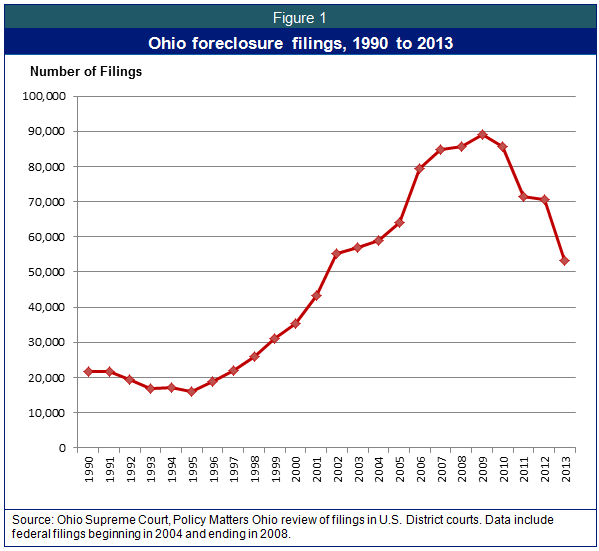

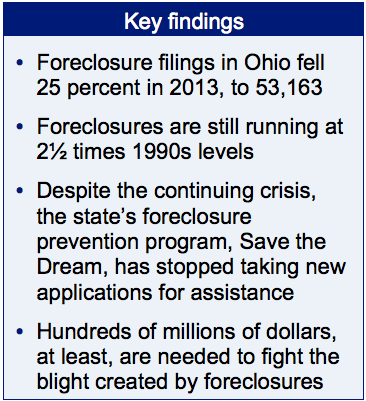

Download summary (1 pg)Download full report (8pp)Press releaseDespite a welcome 25 percent drop, Ohio foreclosures in 2013 remained at highly elevated levels. Last year’s 53,163 new foreclosure filings was 2½ times the average annual total during the 1990s.

Foreclosures in Ohio dropped last year by 25 percent to 53,163, the lowest number since 2002. Despite that welcome news, the number remains at highly elevated levels. Prior to the rise in predatory lending that unfortunately made Ohio a leader in foreclosures starting more than a decade ago, the number of foreclosure filings was far below even 2013 levels. During the 1990s, the number of filings averaged 21,075 a year. Policy Matters Ohio first began issuing annual reports on Ohio foreclosures in 2002. At that time, we analyzed the factors behind the dramatic growth in foreclosure filings, which had reached 43,419 in 2001. In light of this history, last year’s decline is positive news, but still leaves the state feeling the effects of a continued foreclosure crisis.

Foreclosures in Ohio dropped last year by 25 percent to 53,163, the lowest number since 2002. Despite that welcome news, the number remains at highly elevated levels. Prior to the rise in predatory lending that unfortunately made Ohio a leader in foreclosures starting more than a decade ago, the number of foreclosure filings was far below even 2013 levels. During the 1990s, the number of filings averaged 21,075 a year. Policy Matters Ohio first began issuing annual reports on Ohio foreclosures in 2002. At that time, we analyzed the factors behind the dramatic growth in foreclosure filings, which had reached 43,419 in 2001. In light of this history, last year’s decline is positive news, but still leaves the state feeling the effects of a continued foreclosure crisis.

Foreclosures represent a major and ongoing blow against families’ biggest source of savings and financial stability. This report analyzes the new foreclosure filing statistics in Ohio, and makes recommendations to combat the continuing foreclosure crisis and the blight that it has generated.

Data analysis

Ohio foreclosure filings fell to 53,163, compared to 70,469 filings in 2012.[1] The number of filings fell in 84 of the state’s 88 counties. While it was lower than in any year in the past decade, last year’s number was at least double the annual total of every year during the 1990s except 1999 (See Figure 1). Despite the recent drop, since 1995 the number of filings has at least quadrupled in 39 counties and has more than tripled statewide. There was one foreclosure filing for every 96 housing units in the state in 2013.

For the ninth year in a row, Cuyahoga County topped the list of counties with the highest foreclosure rates with nearly 7 foreclosures per 1,000 people (see Table 1). Six of the top 10 counties – Cuyahoga, Preble, Lake, Brown, Hamilton and Clinton – were also among the top 10 with the highest rates in 2012. No. 3 Preble County has been in the top 10 every year since 2007. Other counties also have regularly had among the highest rates. Brown County, No. 8 in 2013, ranked among the top 10 in three of the previous four years. No. 6 Lake County and No. 9 Hamilton County have now found themselves among this group for three years in a row. On the other hand, Erie, Richland and Jackson counties, which were among the top 10 in 2013, had not ranked that high any time over the past decade. Lucas and Montgomery counties, which had been in the top 10 every year from 2004 to 2012, fell out of the top ranking; they ranked 17th and 18th, respectively, in 2013. Summit County also fell out of the top 10 from a year earlier, ranking 12th last year.

Table 1 shows that the number of foreclosure filings is high in counties scattered all over Ohio, north and south, east and west. They include urban, rural and suburban counties – among the top 10 are two of Ohio’s three most populous counties, and four with populations of less than 45,000.

For complete Ohio listings, download: Table 3 - "New foreclosure case filings, 1995-2013"Table 4 - "Foreclosure filings in all Ohio counties, 2013"The largest decreases occurred in Shelby, Adams, Gallia and Wayne counties, each of which saw a drop of more than 40 percent in 2013 from a year earlier. Another 20 counties saw drops of at least 30 percent. As in the past, Cuyahoga County had the highest number of filings with 8,829 as well as the highest foreclosure filing rate in 2013. The decline in filings for the state was mirrored closely by the drop in Ohio’s 10 most populous counties, where the number fell by an almost equal 25 percent. The fall was similar across the big urban counties, ranging from a decline of 23 percent in Cuyahoga County to nearly 30 percent in Montgomery and Butler counties. Two large counties, Stark and Lorain, had lower foreclosure rates per 1,000 people than the state average of nearly 4.6. Table 2 shows foreclosure filings in Ohio’s ten largest counties in 2000 and 2013.

A number of factors have contributed to the declines in foreclosure filing. The wave of predatory lending that sent foreclosure rates climbing starting in the late 1990s crested and fell with the financial crisis. Ohio’s economy, though far from robust, has improved since the recession, causing fewer homeowners to fall behind on their mortgage payments. Efforts to prevent foreclosures have kept many thousands from losing their homes (see below). In some instances, banks may not foreclose on properties because they don’t see enough value in them to do so. [2] And of course, the thousands of vacant and abandoned properties from earlier foreclosures leave fewer candidates for foreclosure now. There are fewer homeowners now in many of the neighborhoods that have been hardest hit with foreclosures, and many of those who previously experienced foreclosures have credit score and employment issues that will make it tough for them to buy again in the near future. The result of these factors and others taken together has been a substantial reduction in the number of foreclosure filings from peak levels.

However, the substantial drop in foreclosure filings last year, following declines in the previous three years from the 2009 peak of more than 89,000, could leave the erroneous impression that foreclosures have returned to normal levels. That would be far from the truth. Take Franklin County, Ohio’s second-largest, and one whose experience mirrors that of the state as a whole. The filing rate per 1,000 people in the county last year was just a tad above that of the state as a whole. In 2013, the number of filings fell 26 percent from a year earlier, to 5,691. That was well below the high in 2010 of 9,649. But in 1995, there were just 1,459 filings in Franklin County; the average number per year between 1994 and 1999 was 2,353. Filings in Franklin County last year were nearly quadruple the number in 1995, and that increase ranked just 43rd among all counties in Ohio over that time period.

The Mortgage Bankers Association’s National Delinquency Survey reports quarterly on the share of loans that are seriously delinquent (90 days or more), along with those already in foreclosure. The latest survey, for the fourth quarter of 2013, shows Ohio continues to have a higher than average level of such loans. Altogether, 6.22 percent of loans were in foreclosure or 90 days overdue, compared to the national average of 5.41 percent.[3] More importantly, although the share of such loans in Ohio is down significantly from its high of 9.63 percent in late 2009, it remains far above 1990s levels, when it was below 2 percent for every quarter but one. The 4th quarter share is twice the rate even during the peak during the 1980s, which included a deep recession with double-digit unemployment rates. And while the number has declined, many Ohio homeowners still owe more on their mortgages than their homes are worth.[4]

In short, despite improvement in Ohio’s housing market that has reduced foreclosures from the stratospheric levels of 2006 through 2010, the problem remains worse than in the early 2000s. As noted in the application made early this year by a broad coalition of Ohio civic groups for a portion of consumer relief funds available because of a legal settlement between the U.S. Department of Justice and JPMorgan Chase & Co., “This long duration means that the consequences of foreclosure – abandonment, blight, plummeting home values, lost property tax revenue, and the cost of blight elimination – have been accumulating in Ohio longer than in most states.”[5] For example, a recent study of 38,931 properties in Cleveland acquired by financial institutions between 2000 and early 2013 after being foreclosed found that 8,697 were tax-delinquent, owing a total of more than $46.3 million in back taxes.[6]

What to do now

The foreclosure problem has many facets, including the failure of regulatory authorities to force the banking industry to write down most of the principal on failed mortgages, and it is beyond the scope of this report to map a comprehensive solution.[7] However, action is needed both to avoid future foreclosures, and to cope with the massive blight that the hundreds of thousands of Ohio foreclosures have left in their path.

The 2012 program year report on Cuyahoga County’s foreclosure prevention program by researchers at Cleveland State University’s Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs noted that, “Local and national research has demonstrated that the centerpiece of this model program, face-to-face foreclosure prevention counseling resulting in a loan modification, is an effective option in terms of helping homeowners stay in their homes. Housing stability benefits homeowners, neighborhoods, cities and the entire country.” The report found that though it has become more challenging to reach a successful outcome, half of the more than 20,000 homeowners who received counseling between 2006 and 2012 were able to achieve that.[8]

Yet despite the importance of foreclosure counseling, on Apr. 30, the Ohio Housing Finance Agency (OHFA) closed new applications to its Save the Dream program, ending the state’s largest effort to help homeowners avoid foreclosure. Under Save the Dream, borrowers had been eligible for up to $35,000 in assistance, which went toward bringing overdue mortgage payments up to date, making mortgage payments for up to 18 months, reducing the principal or paying delinquent property taxes. Applicants were referred to housing counselors around the state, who worked with them to obtain assistance. Altogether, between Sept. 27, 2010, and the end of April, 2014, the program helped 18,886 Ohio homeowners; another 7,992 who registered before the cut-off are expected to be funded.[9] Money for Save the Dream came from Ohio’s $570 million share of the Hardest Hit Fund, a U.S. Treasury Department program.[10] OHFA concluded earlier this year that it had to close off new applications in order to be able to fund all of those in the pipeline. Those who registered prior to April 30 must complete their applications by July 31.

Save the Dream was the primary source of funding for foreclosure counseling that has helped thousands of Ohioans stay in their homes. Only a small share of its funds have gone for counseling; altogether, the housing counseling agencies that work with homeowners under the program had received $20,141,740 through the end of April since the start-up in September 2010. Another key source of funding, the federally funded National Foreclosure Mitigation Counseling Program, is unstable, too, with real uncertainty whether it will continue.[11] OHFA will continue to operate a hotline, referring homeowners who are seeking help to counseling agencies that will accept referrals. However, there are already nine Ohio counties, including Hamilton and Butler, where no agencies are receiving referrals from the state hotline.[12]

With foreclosures still running at double or more the levels of most of the 1990s, foreclosure counseling needs continued support. If federal and private sources are not available, the state should come forward with funding to continue the counseling effort at previous levels. Keeping people in their homes is the best outcome for everyone involved, including the lender.

Even while funding should be continued for counseling, the state faces an enormous challenge in recovering from the damage of the foreclosure crisis. In Cleveland alone, according to the recent study cited above, there are 8,300 homes that are candidates for condemnation out of the 16,000 vacant properties.[13] In what it described as a “very conservative estimate, given the survey relied on voluntary participation and is now more than two years old,” the Thriving Communities Institute (TCI) found that Ohio had 50,000 vacant homes that required demolition. Jim Rokakis, TCI director and a key architect of the land banks that are or will soon be operating in 22 Ohio counties, suggests that the actual number could be double that. Based on a cost of $12,500 per demolition,[14] that means the state faces a problem that is probably worth at least $600 million and possibly closer to $1 billion. And that doesn’t include costs for needed rehabilitation of housing, which is much more expensive.

A recent study for the TCI by the Griswold Consulting Group examined the effects of demolition in Cleveland between 2009 and 2013. It found that though demolition improves values only in areas where the housing market is stronger, it reduces foreclosure activity in general.[15]

Attorney General Mike DeWine designated $75 million from a 2012 national mortgage settlement for demolition of blighted and abandoned homes.[16] Another $60 million from Ohio’s share of the Hardest Hit Fund has been awarded or will be soon to county land banks for buying and removing blighted and vacant residential properties across the state.[17] And Cuyahoga County may be proceeding with a $50 million fund to demolish abandoned structures.[18]

While these efforts are a start, they are insufficient, and demolition is only a piece of the solution. As indicated in the application for a portion of the JPMorgan Chase settlement with the U.S. Justice Department, the state’s vacant property problem is far more substantial than what can be handled with the monies allocated to date. Even that plan, which is still under consideration, would only go part way toward meeting the problem. It calls for:

- $144 million in cash for demolition of dilapidated properties;

- Capitalization of a $16 million fund for counseling to prevent foreclosure and abandonment;

- Capitalization of a $35 million fund to renovate blighted homes; and,

- Capitalization of a $5 million fund to re-purpose vacant land resulting from demolition.

This plan has won widespread support. U.S. Senators Rob Portman and Sherrod Brown wrote a joint letter to JPMorgan Chase asking the bank to consider the proposal.[19] The Plain Dealer editorialized in favor of the plan, which is supported by a wide variety of public officials, local governments, non-profits, land banks, housing counseling agencies and others.[20] Whether or not the proposal is successful, there should be little question about the need for resources to stave off even more foreclosures and to support communities as they combat the effects of this long-running crisis.

There is no perfect measure of foreclosures; the filing data in this report capture the process at one stage, but do not exactly measure the number of families that lose their homes to foreclosure. This report uses data from the Ohio Supreme Court and information compiled in earlier years by Policy Matters Ohio from the two federal district courts in Ohio. The Supreme Court data are filed by county common pleas courts. They are consistent from year to year, allowing a comparison over time and between Ohio's counties (common pleas courts do sometimes amend the data they have previously filed, so totals reported here for earlier years may differ from those cited in prior Policy Matters Ohio reports). As described below, while previous years’ data include federal filings, there are none included after 2008.

The Ohio Supreme Court’s reporting of foreclosure filings includes an unspecified number of non-mortgage foreclosure cases, including delinquent tax foreclosures and others. It also includes double filings that occur if bankruptcy interrupts the process, or if a lender uses the threat of foreclosure as a collection mechanism several times against one borrower. Non-mortgage filings and double filings have not been eliminated from the data. All foreclosure data in this report are for filings. Not all filings lead to actual foreclosures, in which borrowers lose title to their property. On the other hand, filing statistics do not cover all cases in which homeowners lose their property, such as cases in which they give the title back to the lender and walk away from the home.

Policy Matters began compiling federal filings made as of 2004; such cases were not filed in as large numbers prior to that point. After growing significantly, in late 2007 the flow of such cases slowed to a trickle, and the number has not picked up again since. The small remainder included commercial disputes such as alleged non-payment to contractors, filings by the U.S. government for payment in cases of deceased homeowners and a handful of cases by borrowers claiming mistreatment, but virtually no standard filings involving residential properties. Thus, we do not have any federal filings in this report after 2008. As noted in our 2008 report, there is some duplication between state and federal court cases.

In past reports, the previous year’s population data was used because Census estimates were not available for the current foreclosure year. In the 2012 report, the Census population estimates were available and used to calculate foreclosures per 1,000 people.

For complete Ohio listings, download: Table 3 - "New foreclosure case filings, 1995 to 2013" Table 4 - "Foreclosure filings in all Ohio counties, 2013"[1] See note on data at end of the report.

[2] In other cases, banks may start to foreclose on properties, but never complete the process, creating what some call “zombie mortgages” where homeowners may have moved away without realizing that they remain the legal owners See Cleveland Municipal Court Housing Division, Raymond L. Pianka, Judge, “Zombie Mortgages and Zombie Titles,” at http://clevelandhousingcourt.org/zombies.html.

[3] Mortgage Bankers Association, National Delinquency Survey, Fourth Quarter 2003, p. 4.

[5] Ford, Frank and Jim Rokakis, Thiving Communities Institute, Ohio Plan for Application to JPMorgan Chase & Co. Settlement Funds, Jan. 16, 2014, p.3 , at http://www.wrlandconservancy.org/pdf/ChaseOhioPlan.pdf

[6] Ford, Frank et al, “The Role of Investors in the One-to-Three-Family REO Market: The Case of Cleveland,” Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, Dec. 16, 2013, at http://bit.ly/1nsUroI.

[7] Our report last year by David Rothstein, “Home Insecurity 2013: Foreclosures and Housing in Ohio,” Policy Matters Ohio, May 9, 2013, provided a more extensive list of proposals to address the issue, most of which unfortunately remain as relevant today as they were then. See www.policymattersohio.org/foreclosures-may2013.

[8] Hexter, Kathryn and Molly Schnoke, ”Responding to Foreclosures in Cuyahoga County, 2012 Evaluation Report – Revised,” Prepared for Cuyahoga County Department of Development, Prepared by the Center for Community Planning and Development, Cleveland State University Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs, Aug. 1, 2013, at http://bit.ly/1gcBAcv. It defined a successful outcome as: “Bringing their mortgage current, having their mortgage modified, initiating a forebearance agreement, otherwise modifying a mortgage or selling their property through a deed-in-lieu, short sale or pre-foreclosure sale.” See p. 42.

[9] Conversation with Stephanie Casey Pierce, director of homeownership preservation, Ohio Housing Finance Agency, May 6, 2014.

[11] OHFA recently distributed $560,451 through this program to 12 housing counseling agencies (See http://www.ohiohome.org/newsreleases/rlsNFMC2014.aspx). This money covers services since October 2013.

[12] Email from Stephanie Casey Pierce, Ohio Housing Finance Agency, May 6, 2014. While local counseling efforts exist in some of these counties, out-of-state counselors will serve local residents calling in to hotlines there.

[13] Ford et al., op. cit., p. 4. The study’s figure on the number fit to be condemned came from the city’s Department of Building and Housing.

[14] This figure is based on the average cost estimated by the Cuyahoga County land bank for a 1-2 unit property, including an asbestos survey and remediation if necessary, payment if needed to haul out trash, and the demolition itself. Email from Bill Whitney, chief operating officer, Cuyahoga County Land Reutilization Corp., May 5, 2014.

[15] Griswold Consulting Group, “Estimating the Effect of Demolishing Distressed Structures in Cleveland, OH, 2009 to 2013: Impacts on Real Estate Equity and Mortgage Foreclosure,” at http://bit.ly/RrKuwW.

[16] News Release, Feb. 4, 2014, “Attorney General DeWine Awards Additional $3.8 Million in Demolition Grants,” at http://bit.ly/1nsVZze.

[17] Ohio Housing Finance Agency, “OHFA awards 11 counties a portion of $49.5 million to tackle blighted communities,” Feb. 28, 3014, at http://www.ohiohome.org/newsreleases/rlsNIPannouncement.aspx.

[18] Tobias, Andrew J., “Ed FitzGerald introduces plan to create vacant property demolition fund,” http://bit.ly/1fS9J6t.

[19] U.S. Senators Rob Portman and Sherrod Brown, Letter to Stephanie Mudick, Executive Vice President, JP Morgan Chase, Jan. 29, 2014, at http://1.usa.gov/1jlllyF.

[20] “Ohio Should Get a Piece of JPMorgan Chase mortgage-fraud settlement: Editorial,” Jan. 30, 3014, at http://bit.ly/1l2T7rL.

Photo Gallery

1 of 22