Testimony House Finance Subcommittee on Health and Human Services

March 14, 2017

Testimony House Finance Subcommittee on Health and Human Services

March 14, 2017

Contact Wendy Patton 614.221.4505 Download testimony

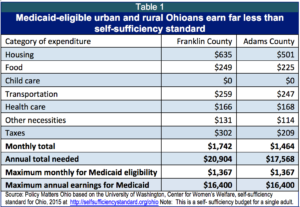

Good morning Chairman Romanchuk, Ranking Member Sykes and members of the Committee. Thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I speak on behalf of Policy Matters Ohio, a non-partisan, not-for-profit research organization with a mission of contributing to a more prosperous, equitable, inclusive and sustainable Ohio.Nearly a thousand people protested to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid against the “Healthy Ohio” waiver proposal submitted by the State of Ohio last year which included, among other things, premiums on adult Medicaid enrollees. The waiver was rejected by the federal government. In this year’s budget, the Kasich Administration again proposes to charge premiums to Medicaid enrollees earning between 100 percent of the federal poverty line – $11,880 a year or $990 a month for a single adult without children – and the income ceiling of 138 percent of poverty – $16,400 or $1,367 a month for a single adult. The Administration’s premium would be set at 2 percent of total income and average $20 per month. Table 1 illustrates that in both urban and rural settings, people eligible for Medicaid live far below the level of self-sufficiency and lack money to pay for premiums.

For people on very limited incomes – like those on Medicaid – premiums decrease use of health care services. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services research found that increased costs make it harder for poor families to access needed health care and maintain coverage. Key findings include:[1]

- Low-income individuals are especially sensitive to increases in medical costs. Modest co-payments can reduce access to necessary medical care.

- Medical fees, premiums, and co-payments contribute to the financial burden on poor adults who need to visit medical providers.

- The problem is even more pronounced for families living in the deepest levels of poverty, who effectively have no money available to cover out-of-pocket medical expenses, including co-pays for medical visits.

A 2014 study published in the Journal of Health Economics found that among the poorest Medicaid enrollees – those earning less than 150 percent of the federal poverty level – a monthly premium of up to $10 results in fewer months of continuous enrollment for adults and children. These effects are concentrated in the first few months of coverage: enrollees are 12 to 15 percent more likely to leave the program within 12 months.[3]

Here in Ohio, MetroHealth Hospital’s early experiment with Medicaid expansion had similar findings: The expansion of readily accessible care, without cost, enhanced health.[4]

Research over many years shows that imposing costs on health care reduces use by poor families or results in discontinuous use. This is because they have limited income. They chose between gas, food, rent, and other bills. Health care falls to the bottom of the pile.

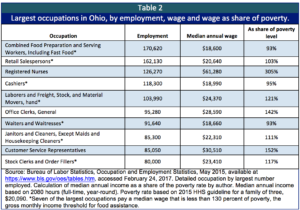

Those who would be hurt the most by premiums are low-income workers in Ohio’s huge low-wage labor market. Families who would be hurt by premiums work in many of Ohio’s largest job categories. A parent with two children working in seven of Ohio’s ten largest occupations would be eligible for Medicaid coverage at the median wage level (Table 2).

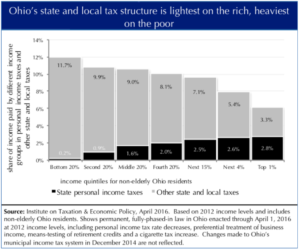

Some say premiums are necessary because the poorest of Ohio’s people must have some “skin in the game.” They do. Ohio’s lowest wage earners on average are contributing twice the share of their total income in state and local taxes as the top 1 percent.

Figure 1, below, shows state and local taxes as a share of income by income quintile. The top quintile is broken out into three categories: the top 1 percent of earners, the top 5 percent and the remaining 15 percent in that quintile.

Those at the bottom of the earning scale –workers filling jobs like those in table 2, who would be affected by the proposed Medicaid premiums – on average paid 11.7 percent of their income in state and local taxes in 2016. The top one percent paid 6.1 percent of income – about half as large a share as the poor.

Figure 1.

Ohio has had real success in providing health care to more people. This has helped people work and get back to work. Unemployed participants interviewed for the Administration’s assessment of the Medicaid expansion overwhelmingly reported that having access to health care made it easier for them to seek employment. The majority of workers enrolled through the expansion reported that Medicaid participation made it easier to continue to maintain their jobs. The report found that even in the short time that has passed since Medicaid expansion, people who gained coverage through it reported gains in physical and mental health status, as well as an increase in financial security and health security.

Charging premiums will prevent Ohioans from getting ahead through better health. Facilitating coverage boosts people, communities and the states. Policies that curtail coverage do the opposite.

Thank you for this opportunity to testify.

[1] Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “Financial Condition and Health Care Burdens of People in Deep Poverty,” United States Department of Health and Human Services, July 16, 2015

[2] Robert H. Brook et.al., “The Health Insurance Experiment: A Classic RAND Study Speaks to the Current Health Care Reform Debate,” http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9174.html

[3] Laura Dague, “The effect of Medicaid premiums on enrollment: A regression discontinuity approach,” Journal of Health Economics 37 (2014) 1-12.

[4] Randall D. Cebul, Thomas E. Love, Douglas Einstadter, Alice S. Petrulis and John R. Corlett, “MetroHealth Care Plus: Effects Of A Prepared Safety Net On Quality Of Care In A Medicaid Expansion Population,” Health Affairs, July 2015 vol. 34 no. 7 1121-1130 at http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/34/7/1121.abstract

Photo Gallery

1 of 22