New rules move the ball forward on home care

June 08, 2015

New rules move the ball forward on home care

June 08, 2015

Contact: Wendy Patton, 614.221.4505

Home-care aides, who provide care for people with disabilities, advanced age or illness, work in one of Ohio’s fastest-growing occupations. However, the home-care industry is riddled with high turnover rates, workforce vacancies and related quality-of-care issues, largely because of low wages, part-time and unpredictable hours, and a lack of benefits.[1] In an earlier report, Low Wages, High Turnover in Ohio’s Home-Care Industry, we recommended the state take steps to improve wages of the publicly funded home-care workforce, including promoting the right of home-care workers to bargain collectively.

Home-care aides, who provide care for people with disabilities, advanced age or illness, work in one of Ohio’s fastest-growing occupations. However, the home-care industry is riddled with high turnover rates, workforce vacancies and related quality-of-care issues, largely because of low wages, part-time and unpredictable hours, and a lack of benefits.[1] In an earlier report, Low Wages, High Turnover in Ohio’s Home-Care Industry, we recommended the state take steps to improve wages of the publicly funded home-care workforce, including promoting the right of home-care workers to bargain collectively.

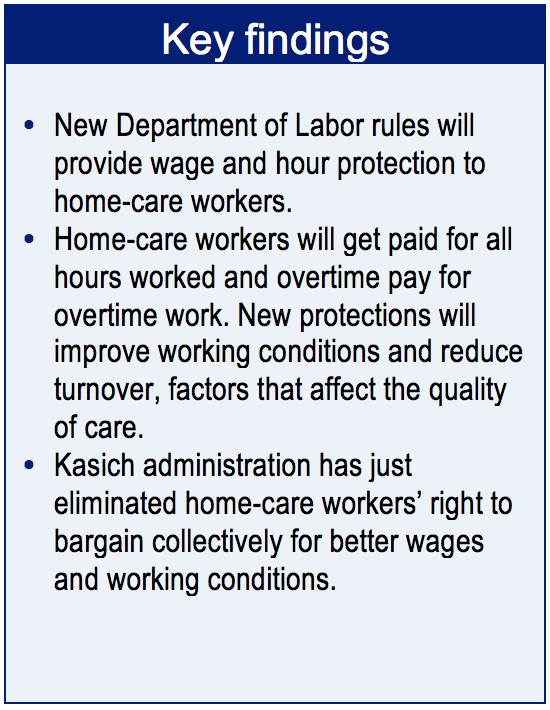

In Ohio, the major impact of the new rules will be on overtime pay, providing (1) payment for all hours worked, including travel time and work performed before or after the official shift and on overnight shifts; and (2) overtime pay. According to Ohio Labor Market Information’s Occupational Employment Statistics (OES), entry-level wages for both home-health aides and personal-care attendants are higher than minimum wage.[2] Workers may actually receive this wage only for their scheduled direct-care hours. The primary benefit of the new rules in Ohio, then, will be application of federal standards for hours worked and overtime pay. There is currently no assurance that home-care workers in Ohio get paid for all hours actually worked or are eligible for overtime pay. The new federal rules would require that home health-care workers are paid for all hours worked and are paid at an overtime rate of one-and-a-half times their regular hourly wage for hours worked above 40 per week.

The home-care industry in Ohio

More than 86,000 people work as home health-care aides or personal-care attendants in Ohio.[3] A recent series in the Columbus Dispatch found many home health-care workers are not paid for the time they drive from the home of one client to the next.[4] Nationally, it is estimated 9 to 12 percent of workers like this work more than 40 hours per week.[5] Studies find turnover in this sector is high because wages are so low.[6]

Public programs – Medicaid and Medicare – finance 80 percent of the work in this industry, which primarily serves older adults and people with physical or developmental disabilities. These public dollars flow either through non-profit and for-profit entities that employ home-care aides, or to independent home-care providers employed directly by the consumers receiving services.[7]

There are about 13,000 “independent providers” in Ohio.[8] These workers can earn higher hourly rates than is typical for their counterparts employed by an agency. According to the Columbus Dispatch, home-health aides, often employed by an agency, earned a median $9.60 per hour in 2013 but independent providers, who work directly for a consumer, can bill Medicaid about $18 for the first hour of care, and about $13 for subsequent hours.[9] The “independent provider” bears costs of independent employment.

Ohio’s outlook for better pay and working conditions in the home-care sector is mixed. On one hand, House Bill 64, the budget bill for fiscal years (FY) 2016-17, contains proposals for some increase in state Medicaid funding for some home health care. At the same time, the Kasich administration proposes to eliminate “independent providers,” in part because of the new federal rules that would ensure minimum wage and overtime protection.[10] Outside of the budget process, Ohio’s Medicaid-funded rates for independent providers is being reduced.”.[11]

In addition, the administration recently ended the right of independent provider home-health workers to bargain collectively.[12] The need for wage and hour protection for home care workers is heightened with loss of the critical right to bargain for better wages and working conditions.

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and new rules to protect home-care workers

The FLSA was passed in 1938 to eliminate child labor, set a minimum hourly wage and establish the maximum hours in the workweek. It did not initially protect domestic workers like cooks, gardeners or servants employed by private households. Congress extended FLSA coverage to domestic workers in 1974, but exempted casual babysitters as well as companions for the aged and infirm, the latter under a provision that came to be known as the “companionship exclusion.” Over time, the exemption was used widely to exclude virtually all workers in the growing home-care industry from wage-and-hour protections.[13]

In 2013, the U.S. Department of Labor announced that rules governing the companionship services exemption would be clarified and wage and hour protection extended to home-care workers. Under the new rules, previously exempt workers are protected if any of the following apply:[14]

- The home-care worker is employed by a home-care agency or other third-party entity.

- The home-care worker provides domestic services on behalf of members of the family of the person being assisted (e.g. laundry or cleaning for the patient’s daughter).

- The home-care worker provides medical services that typically require and are performed by trained medical personnel because they are invasive, sterile or otherwise require medical judgment (e.g. assisting with tube feeding or catheter care).

- The home-care worker spends more than 20 percent of his or her time in a work week (per consumer) assisting with activities of daily living (e.g. dressing, grooming, feeding, bathing and toileting) or instrumental activities of daily living (e.g. meal preparation, driving, managing finances, and arranging medical care).

A federal district court vacated the provisions of the new rules outlined above in two decisions, one in December 2014 and another in January 2015. The judge said that the Department of Labor could not bar third-party employers like home-care agencies from qualifying for the companionship exemption. He also threw out parts of the rule that narrowed the definition of exempt companionship services for home-care workers (items 2, 3 and 4, above). The Department of Labor has appealed the decisions.[15]

It is important to note that the new rules had other provisions that were not struck down, including new record-keeping and time-keeping provisions. It also clarifies, without changing the law, information regarding third-party and joint employment relationships, independent contractors, and other areas such as sleep time.[16] These clarifications and provisions will benefit all home-care workers, including those exempted from FLSA coverage at present, when the new rules take effect.

Record keeping: Prior to the new rule, employers were not required to keep records of the actual hours home-care employees worked, but could instead maintain a copy of an employment agreement that set forth agreed-upon hours. Any variance from the agreement had to be recorded, reflecting the actual hours worked. The new rule permits employers to record hours or to delegate the recording of hours to the employee, who must then submit an accurate record of actual hours worked. The employer is responsible for maintaining records.[17]

Advocates consider the revision an improvement because it establishes a process for recording hours worked each week, whereas the previous approach might have meant that employers frequently overlooked extra work that home-care providers did. (See Appendix for the Department of Labor’s detailed definitions of what is work, what must be counted as “on the clock”, what is off the clock, what records must be kept and how.)

Employment relationships: Who is the employer? : If time sheets are to be kept for home-care workers, who keeps the time and pays overtime for independent providers who serve several clients? The new rules do not change the definition of employer, but clarify that the standard for determining an employment relationship under the FLSA is the “economic realities test,” a different standard than in other statutes, including the Internal Revenue Code and many state laws. While we sometimes assume the employer is the tax withholder, in the “economic realities test,” the factors to consider include (but are not limited to):

- Whether an employer has the power to direct, control, or supervise the worker or work performed;

- Whether an employer has the power to hire, fire, modify employment conditions or determine pay rates or methods of payment for the worker;

- The degree of permanency and duration of the relationship;

- Where the work is performed and whether tasks require special skills;

- Whether the work performed is an integral part of the overall business operation;

- Whether an employer undertakes responsibilities in relation to the worker(s) which are commonly performed by employers;

- Whose equipment is used, and;

- Who performs payroll and similar functions[18]

Rules on sleep time, shared living:[20] The new rules were designed to update and clarify the companionship exemption for domestic workers. In some cases, an employee sleeps over at a client’s house. The rule does not change existing sleep time rules. However, because the DOL received many comments and questions about sleep time for domestic service workers, including several that conflated live-in employees with employees working one or more 24-hour shifts, it set forth clarifications in the rule on existing law.

Many service delivery models fall under the broad definition of “shared living." This can include adult foster care, host homes, and paid roommates. To help providers and patients better understand when these arrangements are considered “employment” under the FLSA, the DOL issued guidance, which breaks down models into three basic types of shared living:[21]

- The consumer lives in a provider’s home: The primary question in this type of shared living arrangement is whether there is an employment relationship to which FLSA requirements apply – that is, whether the provider is an employee of the consumer and/or a third party who finances the cost of providing care to the consumer, or is instead an independent contractor.

- The provider lives in the consumer’s home: These arrangements are sometimes called roommate arrangements. Typically, the provider lives rent-free in the consumer’s home and might or might not receive additional payment. These arrangements are often funded by Medicaid but may also be funded by another public program or privately. The threshold issue in these types of shared living arrangements is whether the consumer is the sole employer (and if so, whether an exemption applies) or whether there also is a third party that is a joint employer.

- The provider and consumer move into a new home together: Whether these situations are more like those described in Scenario #1, above (shared living in a provider’s home) or Scenario 2 (shared living in a consumer’s home) depends upon all of the circumstances that go to who controls the residence and relationship. Relevant facts include who identified the residence, arranged to buy or lease it, furnished common areas, maintains the residence (for example, by cleaning it and making repairs), and pays the mortgage or rent. No single fact alone is controlling.

Conclusion

New FLSA rules would extend all wage and hour protections enjoyed by most American workers to the growing ranks of home-care workers. Employer groups challenged the rules and a federal district court has struck down significant sections of the rules, but the Department of Labor has appealed. If the DOL wins its appeal, Ohio’s home-care workers will be eligible for the protection of federal minimum wage and overtime pay rules.

More than 86,000 work in the home-care industry in Ohio. Many are not paid for hours they are on the job, like hours spent traveling between the homes of consumers they serve. Up to 12 percent of home-care workers are on the job more than 40 hours per week, but they are not paid overtime. Wage and hour protections for home-care workers are badly needed. With fair timekeeping, pay for hours worked and overtime pay when applicable, home-care workers will be able to make ends meet. The result will be a more stable home-care sector, a more skilled workforce and better care for vulnerable Ohioans.

APPENDIX: Time keeping and record keeping as defined by the United States Department of Labor

What is overtime?[22]

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) provides a definition of overtime. Employees covered by the FLSA must receive overtime pay when they work more than 40 hours in a work week. Overtime pay must be at least 1.5 times the regular rate of pay. The act does not limit hours for workers over 16, nor does it specify overtime pay for weekend or holiday work if the work week is still less than 40 hours.

Overtime protection applies by the week. An employee's work week is a fixed and regularly recurring period of 168 hours — seven consecutive, 24-hour periods. It need not coincide with the calendar week, but may begin on any day, at any hour. Different work weeks may be established for different employees or groups of employees. An employer cannot average hours over two or more weeks. Normally, overtime pay earned in a particular work week must be paid on the regular payday for the pay period in which the wages were earned.

Work includes a category of paid time that is considered “suffered or permitted.” Work not requested but suffered or permitted is work time that must be paid for by the employer. For example, an employee may voluntarily continue to work at the end of the shift to finish an assigned task or to correct errors. The reason is immaterial. The hours are work time and must be paid. Fact sheets from the Department of Labor give examples of “Suffered or permitted” work:

- Waiting Time: Whether waiting time is hours worked under the Act depends upon the particular circumstances. Generally, the employee was ‘engaged to wait’ (which is work time) or was ‘waiting to be engaged’ (which is not work time). For example, a secretary who reads a book while waiting for dictation or a firefighter who plays checkers while waiting for an alarm is working during such periods of inactivity.

- On-Call Time: An employee who is required to remain on call on the employer's premises is working while on call. An employee who is required to remain on call at home, or who is allowed to leave a number where he/she can be reached, is not working (in most cases) while on call.

- Rest and Meal Periods: Rest periods of short duration, usually 20 minutes or less, are common in industry, promote the efficiency of the employee, and are customarily paid for as working time. These short periods must be counted as hours worked. Unauthorized extensions of authorized work breaks need not be counted as hours worked when the employer has expressly and unambiguously communicated to the employee that the authorized break may only last for a specific length of time, that any extension of the break is contrary to the employer's rules, and any extension of the break will be punished. Bona fide meal periods (typically 30 minutes or more) generally need not be compensated as work time. The employee must be completely relieved from duty for eating regular meals. The employee is not relieved if required to perform any duties, whether active or inactive, while eating.

- Sleeping Time and Certain Other Activities: An employee who is required to be on duty for less than 24 hours is working even though he/she is permitted to sleep or engage in other personal activities when not busy. An employee required to be on duty for 24 hours or more may agree with the employer to exclude from hours worked bona fide regularly scheduled sleeping periods of not more than 8 hours, provided adequate sleeping facilities are furnished by the employer and the employee can usually enjoy an uninterrupted night's sleep. No reduction is permitted unless at least 5 hours of sleep is taken.

- Lectures, Meetings and Training Programs: Attendance at lectures, meetings, training programs and similar activities need not be counted as working time if four criteria are met, namely: it is outside normal hours, it is voluntary, it is not job related, and no other work is concurrently performed.

- Travel Time: The principles, which apply in determining whether time spent in travel is compensable time, depend upon the kind of travel involved.

- Home to Work Travel: An employee who travels from home before the regular workday and returns to his/her home at the end of the workday is engaged in ordinary home to work travel, which is not work time.

- Home to Work on a Special One-Day Assignment in Another City: An employee who regularly works at a fixed location in one city is given a special one-day assignment in another city and returns home the same day. The time spent in traveling to and returning from the other city is work time, except that the employer may deduct or not count time the employee would normally spend commuting.

- Travel That is All in a Day's Work: Time spent by an employee in travel as part of their principal activity, such as travel from job site to job site during the workday, is work time and must be counted as hours worked.

- Travel Away from Home Community: Travel that keeps an employee away from home overnight is travel away from home. Travel away from home is clearly work time when it cuts across the employee's workday. The time is not only hours worked on regular working days during normal working hours but also during corresponding hours on nonworking days. As an enforcement policy the Division will not consider as work time that time spent in travel away from home outside of regular working hours as a passenger on an airplane, train, boat, bus, or automobile.

Record-keeping requirements

Record-keeping requirements are listed under the FLSA's recordkeeping regulations, 29 CFR Part 516. Employers are required to display an official poster outlining the provisions of the Act (available electronically for downloading and printing at http://www.dol.gov/osbp/sbrefa/poster/main.htm.)

Every covered employer must keep certain records for each worker covered under the FLSA. The Act requires no particular form for the records, but does require that the records include certain identifying information about the employee and data about the hours worked and the wages earned. The law requires this information to be accurate. The basic records an employer must maintain include:

- Employee's full name and social security number.

- Address, including zip code.

- Birth date, if younger than 19.

- Sex and occupation.

- Time and day of week when employee's workweek begins.

- Hours worked each day.

- Total hours worked each workweek.

- Basis on which employee's wages are paid (e.g., "$9 per hour", "$440 a week", "piecework")

- Regular hourly pay rate.

- Total daily or weekly straight-time earnings.

- Total overtime earnings for the workweek.

- All additions to or deductions from the employee's wages.

- Total wages paid each pay period.

- Date of payment and the pay period covered by the payment.

[1] Amanda Woodrum, “Low wages, high turnover in Ohio’s home-care industry,” Policy Matters Ohio, April 2015 at http://bit.ly/1AAu76s

[2] Since the 2006 passage of the Fair Minimum Wage Amendment (FMWA) to the Ohio Constitution, home health care workers are covered by the minimum wage. The language of the Constitutional amendment (now Article 2, Section 34a of the Ohio Constitution) is broad and, as held by the Ohio Court of Appeals for the Second District, in Haight v. Cheap Escape Co., 2014-Ohio-2447, does not incorporate most FLSA exemptions, such as the one for home health care workers. Workers who are not exempt are covered. However, because of a discrepancy between the FMWA and the enabling legislation passed by the Ohio legislature, some employers have asked whether the exemptions for certain workers under the current FLSA regulation apply in Ohio. An appeal of the appellate decision in the Haight case, which involved outside salespeople, has been accepted by the Ohio Supreme Court. Nevertheless, because most home health care workers in Ohio are paid at or above the minimum wage for direct-care hours, the real effect of the new DOL regulations involves pay for travel time and overnight hours and overtime pay.

[3] Woodrum, Op.Cit.

[4] “Aides generally use their own vehicles, buy their own gas and, in some cases, don’t get to stay on the clock between clients.” Rita Price and Ben Southerly, “Home health care for vulnerable Ohioans leans hard on poorly paid workers,” The Columbus Dispatch, December 15, 2014 at http://bit.ly/1d1ZZpU.

[5] Home Care Jobs: The Straight Facts on Hours Worked, Value the Care #6, February 2012, at: http://www.PHInational.org/fairpay. Also see in-depth information presented in D. Seavey and A. Marquand (December 2011) Caring in America, Bronx, NY: Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute, available at: http://www.phinational.org/homecarefacts. Cited in Dorie Seavy and Alexandra Olins, Can Home Care Companies Manage Overtime Hours? Three Successful Models, Paraprofessional Helathcare Institute (2012) at http://bit.ly/1FQiQ2z. Department of Labor estimates 12 percent of home care workers work unpaid overtime. See General Accountability Office, Fair Labor Standards Act: Extending Protections to Home Care Workers, (GAO-15-12), p.18, December 2014 at http://www.gao.gov/assets/670/667601.pdf

[6] Paying the Price: How poverty wages undermine home care in America, Paraprofessional Health Institute at http://bit.ly/17mF1ip.

[7] Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, National Expenditure Report for 2013, at http://go.cms.gov/1qiUAfG; see also Seavey & Marquand, PHI, Caring in America, cited in Woodrum, Op. Cit.

[8] Ben Southerly and Rita Price, State Liability Drives Plan to Phase Out Independent Providers, The Columbus Dispatch, March 15, 2015 at http://bit.ly/1EoW6BJ.

[9] Ben Southerly and Rita Price, Kasich’s Budget Plan Aims at Medicaid Fraud,” The Columbus Dispatch, February 3, 2015 at http://bit.ly/1zaHV4P.

[10] Initially, the state pointed to fraud as the reason for eliminating this class of workers, but Office of Health Transformation director Greg Moody subsequently told the Columbus Dispatch that the reason for the proposed elimination of independent providers was the new federal labor rule that says home-care workers are entitled to minimum wage, overtime and travel reimbursement.. See Southerly and Price, “State liability drives plan to phase out independent contractors, The Columbus Dispatch, March 15 2015 at http://bit.ly/1EoW6BJ

[11] Gongwer Ohio, “Amid Opposition, JCARR Lets Controversial Rule On Home Health Care Rates Stand, June 1,2015 at http://www.gongwer-oh.com/programming/news.cfm#sthash.Y9OTzt44.dpuf

[12] Jeremy Peltzer, John Kasich halts union rights for home health care, child care workers,” Northeast Ohio Media Group, May 22 2015 at http://bit.ly/1F1D1FT.

[13] By Paul K. Sonn, Catherine K. Ruckelshaus and Sarah Leberstein, Fair Pay for Home Care Workers:

Reforming the U.S. Department of Labor’s Companionship Regulations Under the Fair Labor Standards Act, National Employment Law Project< August 2011 at http://bit.ly/1FjgLbw

[14] Analysis provided in a memo from Christina Williams, a student of the Cleveland-Marshall College of Law, to Wendy Patton, dated April 24, 2015.

[15] Frank Hupfl, The Companionship Exemption Remains: DC District Court’s Most Recent Decision in Home Care Association of America v. Weil Marks Second Victory for Home Care Employers; DOL Appeals, Mintz Levin Employment Matters blog, January 23, 2015 at http://bit.ly/1LLRETk

[16] Katherine Berland, Esq., Director of Public Policy, “The Impact for Providers of the Court Rulings in Home Care Association of America v. Weil (Case No. 14-cv-967) Regarding the Department of Labor Final Rule RIN 1235-AA05, Application of the Fair Labor Standards Act to Domestic Service (Home Care Rule)”, Memo to members of ANCOR (American Network of Community Options and Resources), February 5, 2015

[17] Id.

[18] DOL, Administrator’s Interpretation No. 2014-2, p. 3 (June 19, 2014) available at http://www.dol.gov/whd/opinion/adminIntrprtn/FLSA/2014/FLSAAI2014_2.htm (citing 29 C.F.R. Part 791; 29 C.F.R. 500.20(h); Charles v. Burton, 169 F.3d 1322 (11th Cir.), cert. denied, 528 U.S. 879 (1999); Lopez v. Silverman, 14 F.Supp.2d 405 (S.D.N.Y. 1998)).

[19] United States Government Accountability Office, “Fair Labor Standards Act: Extending Protections to Home Care Workers (GAO-15-12), p.29, December 2014 at http://www.gao.gov/assets/670/667601.pdf

[20] Katherine Berland, Op.Cit.

[21] This was not part of the new FLSA rules, but the questions were raised and so guidance was offered by the DOL as part of clarifying the new rules. See United States Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, “Fact Sheet #79G: Application of the Fair Labor Standards Act to Shared Living Programs, including Adult Foster Care and Paid Roommate Situations,” March 2014 at http://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/whdfs79g.htm

[22] This section taken from the United States Department of Labor factsheets at http://www.dol.gov/whd/homecare/finalrule.htm

[23] United States Department of Labor, “Fact Sheet #22: Hours Worked Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) at http://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/whdfs22.htm

[24] United States Department of Labor, “Fact Sheet #21: Recordkeeping Requirements under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)” at http://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/whdfs21.pdf

Tags

2015Minimum WageWendy PattonWork & WagesPhoto Gallery

1 of 22