Keys for Collateral: How auto-title loans have become another vehicle for payday lending in Ohio

December 18, 2012

Keys for Collateral: How auto-title loans have become another vehicle for payday lending in Ohio

December 18, 2012

Download reportExecutive summaryPress releaseLenders have circumvented Ohio legislation designed to limit payday lending, and have begun operating under laws intended for other purposes. These loans put struggling families at risk of losing the vehicles they depend on for their livelihood.

Policy Matters has conducted research on payday lending in Ohio for the last five years. Our initial research found that the payday lending industry grew from just over 100 stores in the mid‐1990s to more than 1,600 stores in 2007, with  stores in 86 of Ohio’s 88 counties. Our concern with Ohio’s prior Check Cashing Lending Law, which legalized payday lending in 1996, was that lenders could charge an annual percentage rate (APR) of 391 percent, $15 for every $100 borrowed.

stores in 86 of Ohio’s 88 counties. Our concern with Ohio’s prior Check Cashing Lending Law, which legalized payday lending in 1996, was that lenders could charge an annual percentage rate (APR) of 391 percent, $15 for every $100 borrowed.

Our research found that a basic family budget for families making less than $45,000 a year would leave them ill‐equipped to pay back a payday loan given the short time frame and high cost of the loan. In fact, families facing a financial shortfall would barely have the money to pay back the principal of the loan in two weeks, much less the principal plus high interest and origination fees. Most recently, two new forms of payday lending have taken hold in Ohio, which involve using a title for an automobile as collateral and lending under a statute meant for credit repair.

Payday lending in Ohio, a brief history

Concerns from Policy Matters and others over the high fees and short time period for payback were echoed by the Ohio General Assembly and former Governor Ted Strickland. By signing H.B. 545 in the 2010 session, Ohio repealed the Check‐Cashing Lender Act and replaced it with the Short‐Term Loan Act. This was supported by a 2:1 ratio by Ohio voters in November when Issue 5 passed. This act instituted the following provisions:

- An APR cap of 28 percent on fees and interest regardless of amount borrowed;

- 31‐day minimum term;

- A cap of four loans per year; and

- A maximum of $500 borrowed at one time.

Although the Ohio General Assembly, Governor Strickland, and Ohio voters affirmed their support for a 28 percent APR rate cap and 31‐day minimum loan term, payday lending in Ohio remains virtually unchanged. In fact, many companies are making loans at higher costs than before the law passed under the Ohio Small Loan Act, Credit Service Organization Act, and Mortgage Loan Act. These previously existing laws allow payday have allowed companies to continue issuing loans in Ohio, under the same kind of exploitative terms that lawmakers and voters tried to abolish. Instead of registering and operating under the new law, lenders have simply circumvented the Ohio legislation and begun operating under laws intended for another purpose. In terms of transparency and cost, they may even have gotten worse. In past reports and news coverage, lenders using the Small Loan Act and Mortgage Loan Act were found to:

- Issue the loan in the form of a check or money order and charge a cashing fee. By charging the borrower a 3 to 6 percent fee for cashing the lender’s own out‐of‐state check (a check that presents no risk to the lender of insufficient funds), the cost of a $200 loan can climb to higher than 600 percent APR;

- Sell online loans, brokered through stores, which carry larger principal and are even more expensive. On a $200 loan, a borrower could pay between $24 and $34 more for a loan online than in the company’s store;

- Accept unemployment, Social Security, or disability checks as collateral.

Another method of circumvention, the Credit Service Organization

The rationale for having state and federal Credit Service Organization (CSO) laws was to protect consumers from credit service repair organizations that charged high fees and provided little helpful service to clients. Ohio defines a CSO as a party that takes payment for:

- Improving a buyer’s credit record, history or rating;

- Obtaining an extension of credit by others for a buyer;

- Providing advice or assistance to a buyer in connection with the above;

- Removing adverse credit information that is accurate and not obsolete from the buyer’s credit record, history or rating; and

- Altering the buyer’s identification to prevent the display of the buyer’s credit records, history or rating.[1]

The CSO model for payday lending involves three parties: the payday company with the CSO license, a third-party lender, and the borrower. Payday lenders obtain a CSO license from the Ohio Department of Commerce and offer to provide the services listed above by connecting them to a payday loan, provided by a third-party lender. The third-party lender has a license from the Ohio Department of Commerce to lend under the Mortgage Loan Act or Small Loan Act.

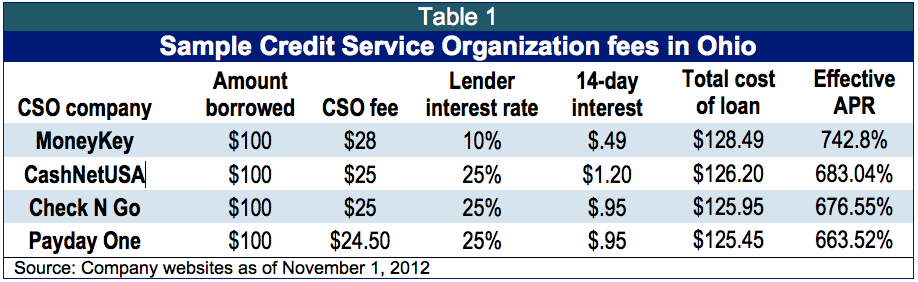

Under the CSO model, the payday lender charges a brokering fee (usually $25 per $100) and the third-party lender charges fees and interest on the loan (usually 25 percent of the principal). The CSO payday lending model has opened the door to a form of lending that uses an automobile title as collateral, which we discuss in the next section. Some lenders, including Ohio Neighborhood Finance, LLC (doing business as Cashland), have a minimum loan amount for their CSO auto title loan of $1,500. Table 1 shows some sample fees and terms on a $100 loan from four CSOs in Ohio. The total cost of the loan refers to the total amount due when the loan period is complete.

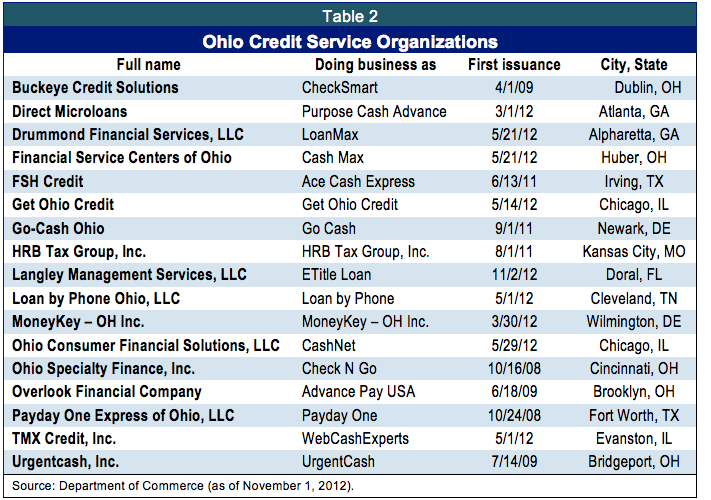

As of November 1, 2012, there were 36 CSOs registered with the Ohio Department of Commerce. Seventeen of the CSOs in Ohio are payday and auto-title lenders either selling storefront or online loans. Another CSO is the paid tax preparation chain, H&R Block.

Based on our research and existing studies of the CSO payday loan model in other states, we raise the following concerns:

- First, the CSO model is being used for the express purpose of getting around the Short Term Loan Act in order to charge higher interest and fees to the consumer;

- Second, the CSO model is more expensive and allows for larger loan amounts than the storefront payday loan. The average payday loan size is $300; the CSO loan maximum amount is significantly higher;

- Third, the CSO statute requires the arranger and provider of credit to be separate entities, otherwise the CSO would be violating the state usury rate cap. There is evidence that this is not the case in Ohio, as many of the active lenders have no infrastructure or storefronts in Ohio. The CSO is not in fact shopping around for the best credit deal possible for the client, but rather extending them a pre-determined loan package. The CSO accepts and collects payments for these loans in Ohio, suggesting they should be considered the true lender and licensed under a different Ohio law;

- Finally, there is a real question as to the value of the payday CSO model. Since the CSO model is used solely to evade Ohio’s 28 percent rate cap, there is no evidence that legitimate credit repair services are being offered to or performed for borrowers.

Auto-title lending

Beginning in 2012, Policy Matters and community members around Ohio began tracking a new development in the payday loan marketplace.[2] Our investigation shows that at least two companies in Ohio are making payday loans using the title of an automobile rather than a paycheck as security. This form of lending is concerning for three main reasons: Like storefront payday lending, auto-title lending carries a triple digit APR, has a short payback schedule, and relies on few underwriting standards; the loans are often for larger amounts than traditional storefront payday loans; and auto-title lending is inherently problematic because borrowers are using the titles to their automobiles as collateral, risking repossession in the case of default.

Auto-title lenders in Ohio are selling loans under two state lending laws. One company, Ace Cash Express, directly sells auto-title loans using the Ohio Mortgage Loan Act. Except for Ace’s use of auto titles rather than post-dated checks as collateral, these loans look like the traditional storefront payday loan. Through store visits, phone calls, public records requests, and online research, Policy Matters explored how this model of auto title lending currently works in Ohio.

Some Ace stores advertise $800 as a loan limit for the auto-title loan; however, brochures and applications advertise lending up to $1,000. To purchase the loan, borrowers must provide photo identification, clear title to the automobile, and the vehicle. After the automobile is assessed and photographed by Ace employees, the rest of the application mirrors the traditional storefront payday loan. We were told twice during our investigation that borrowers must also provide checking account information but do not need current employment for the loan. A third time we were told that providing bank account information is not required. When it makes the loan, Ace puts a lien on the title. Borrowers cannot sell or transfer the car or renew their licenses while the lien is in place. Ace keeps the car title but does not transfer the title name; it is returned when the full loan is repaid. [3]

Table 3 shows the fees for the auto-title loan sold by Ace. These fees mirror the storefront payday loan schedule, which uses the Mortgage Loan Act.

The other method for auto-title lending uses the CSO model described above. One company, LoanMax, a licensed CSO, sells auto-title loans by brokering loans with a third party. Their website and loan application states: “In Ohio, LoanMax is not a lender, but rather a Credit Services Organization that can assist you in obtaining a loan from an unaffiliated third party. Certificate #: CS.900135.000.

There are several differences between using the CSO license and the Ohio Mortgage Loan Act license that Ace uses to sell its loans. First, LoanMax’s 30-day loan term is longer than the term of two weeks or less at Ace and traditional storefront lenders. There is also the option of paying some interest and principal on the loan, often known as a rollover. Second, LoanMax store employees told our researchers that they put the title in LoanMax’s name after the loan is sold and change it back once the loan is repaid. It is possible that store employees did not completely understand how the title lien process works.[4] Third, the loan amount for the CSO auto-title loan can be much higher. Stores varied in their responses to what the maximum loan amount could be, with quotes ranging from $2,500 to $10,000. The loan amount can depend on the value and condition of the automobile, store policy, and requested amount by the borrower.

When asked the cost of the loan and repayment options on a $500 loan, we were told it would cost $161.77, due in one month (30 days). The APR for this loan, assuming CSO, loan origination, and lien fees are included in the transaction, would be 393 percent. We were told that when the loan comes due, if a full repayment cannot be made, a client has the option of making a partial payment with interest. What was unclear, both over the phone and in person, was how the fees are structured to the CSO and the third party lender. For a fee breakdown, we looked to a contract from an Ohio borrower.

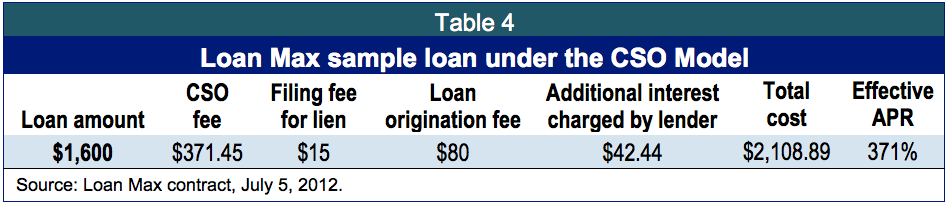

Table 4 provides a sample fee schedule for a LoanMax auto-title loan that we received from a credit counselor who was helping an Ohioan repay the debt from the loan. In this example, the lender is Integrity Funding Ohio, LLC – located in South Carolina and licensed under Ohio’s Second Mortgage Lending Act.[5] Note that the loan amount is substantially higher than the average payday loan of $300.

New developments, court cases and payday lending in Ohio

Recent court decisions support a crackdown on lenders using the CSO and Mortgage Loan Act to make short-term, single payment loans. The Ohio Ninth District Court of Appeals ruled in favor of a lower court decision, which stated that a payday lender could not use the Mortgage Lending Act to collect interest on a short-term, single payment loan.[6] The court said a lender must be licensed under the Short Term Loan Act to charge and collect 28 percent interest, ruling that if the lender does not have the correct license, then it can only charge and collect interest at the usury rate of 8 percent. While this decision currently applies to the Ninth District (Lorain, Medina, Summit, and Wayne counties), a supportive ruling by the Ohio Supreme Court would set precedent statewide. Using the CSO and Mortgage Loan Act to make auto-title loans, using their current interest rates, would also be impermissible based on this ruling.

Recommendations

Policymakers have the opportunity to protect consumers and enforce Ohio’s lending and credit laws. Two public policy suggestions would immediately end the purposeful circumvention of Ohio laws.

Enforce the CSO law. Neither traditional payday nor auto-title loans should be permitted under Ohio’s CSO law. The Ohio Department of Commerce and the state’s attorney general have the authority and documentation to end the practice of making payday and auto-title loans under the CSO statute. Commerce can and should revoke the licenses of the CSO and lender for those companies involved in this scheme to evade Ohio’s lending laws. With half of the CSO licensees in Ohio being payday or auto-title lenders, it is clear the statute is being abused and immediate action is needed. Commerce and the attorney general must ensure that licensees comply with both the letter and purpose of Ohio’s lending laws.

End auto-title lending. The Ohio General Assembly should add a clause to legislation that specifically prohibits auto-title lending. The loss of a crucial asset like an automobile to predatory, short-term lenders should not be allowed in Ohio. A family that loses an automobile will be less likely to get to work, school, or a grocery store, and face increasing economic instability as a result.

[1] Ohio Revised Code 4712.1, available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/4712.

[2] Jeff Piorkowski. “South Euclid Officials Displeased with Mayfield Road Lending Business,” Sun News (Aug. 2, 2012)

[3] During our investigation, we noted that Ace put forward a new company policy not to disclose fees over the phone. The stores we reached in Northeast Ohio would not provide loan costs over the phone, citing this new company policy, but did refer us to their website.

[4] Since Policy Matters Ohio did not purchase an auto-title loan, we do not have direct evidence of how the title changing process works.

[5] SM.501789.000. Issuance date of 4/16/2012.

[6] Sheryl Harris. “State Appeals Court Restricts Payday Lenders’ Interest Rates,” Cleveland Plain Dealer (Dec. 3, 2012).

Tags

2012Consumer ProtectionDavid RothsteinPhoto Gallery

1 of 22